| Sahyadri Conservation Series: 23 |

ENVIS Technical Report: 53, May 2013 |

|

Status of Forest in Shimoga District, Karnataka |

|

1Energy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560012, India.

2Member, Western Ghats Task Force, Government of Karnataka, 3Member, Karnataka Biodiversity Board, Government of Karnataka

*Corresponding author: cestvr@ces.iisc.ac.in

TRAGEDY OF THE KAN SACRED FORESTS

Ramachandra T.V, Subash Chandran M D, Ananth Ashisar, Rao G R, Bharath Settur and Bharath H. Aithal, 2012. Tragedy of the Kan Sacred Forests of Shimoga Doistrict: Need for Urgent Policy Interventions for Conservation, CES Technical Report 128, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012

TRAGEDY OF THE KAN SACRED FORESTS OF SHIMOGA DISTRICT: NEED FOR URGENT POLICY INTERVENTIONS FOR CONSERVATION

(CASE STUDIES OF KURNIMAKKI-HALMAHISHI AND KULLUNDI KANS OF THIRTHAHALLI)

Study carried out for Vriksha Laksha' Andolan, Sagar Taluk, Shimoga

Western Ghats Task Force, Government of Karnataka

| T.V.Ramachandra1,2 |

M.D.Subash Chandran1,3 |

Ananth Ashisar4 |

| G.R. Rao1 |

Bharath Settur1 |

Bharath H. Aithal1 |

| Sreekanth Naik1 Prakash Mesta1 |

1Energy & Wetlands Research Group, CES,IISc, 2Member, Western Ghats Task Force

3Member, Karnataka Biodiversity Board, GOK, 4Chairman,Western Ghats Task Force, GoK |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The kan forests of Central Western Ghats of Karnataka, were most often climax evergreen forests, preserved through generations by the village communities of Malnadu regions, as sacred forests, or sacred groves, dedicated to deities and used for worship and cultural assemblage of the local communities. Various taboos and regulations on usage of the kans were self-imposed by the local communities. In the normal course trees were never to be cut, but the adjoining villagers enjoyed the privileges of taking care and gathering of wild pepper, that was abundant in the kans, and many other non-wood produce, demarcating portions of the kans informally between the different families for collection purposes.

The kans functioned as important sources of perennial streams and springs used for irrigation of crops and for domestic needs. They moderated the local microclimate favouring the spice gardens in their vicinity, and were also fire-proof being evergreen in nature.

The landscape of pre-colonial times had kans forming mosaic with secondary, timber rich forests, grassland and cultivation areas, promoting also rich wildlife.

Kans were characteristic in the traditional land use of Shimoga, Uttara Kannada and Chikmagalur districts specially, and were equivalent to the devarakadus of Kodagu region.

With the domination of Central Western Ghats region of Karnataka by the British, the State asserted its control over the kan lands, which were in thousands, each kan measuring originally from few hectares to several hundred hectares in area. The curtailment of community rights in the kans, including heavier taxation for collection of forest produce resulted in the abandonment of many of them, causing various hardships to the villagers.

Whereas most kans of Uttara Kannada got merged with the rest of the forests ensuring the conservation of rare and endemic species of Western Ghats, in Shimoga district the kans were not properly documented except in Sorab taluk and to some extent in Sagar and Thirthahalli taluks. Moreover the Shimoga kans were brought under either the forest or revenue departments. As communities lost their traditional biomass collection privileges in secondary deciduous forests, in many places they resorted to kans for fuelwood, timber and leaf manure, causing their decline.

As the kans were not of much timber value due to the growth of easily perishable softwoods in them, the British thought it suitable to keep many such under the control of the revenue department. The revenue authorities started allotting these precious watershed areas and reserves of biodiversity for expansion of cultivation, especially of coffee and garden crops, creating widespread fragmentation of the kans. The practice of allotments ranging in area per applicant, individual or organization varied from one or two acres to hundreds of acres each. As the kansunder revenue department was given more importance as land resources than as forests, the forests were cleared partially or entirely for alternative land uses.

The rampant use of fire for clearing the evergreen vegetation for cultivation areas or creating grassy areas caused change of climax evergreen vegetation to savannas, scrub and secondary deciduous forests with diminished water flow in the streams and rivers, which can be detrimental to the livelihoods of people in malnadu and beyond even in the drier Deccan plains.

Large chunks of kanlands were allotted to the Mysore Paper Mills for raising of pulpwood plantations, especially in Shimoga district.

Soil erosion, consequent on the clearance of kans, has adversely affected forest regeneration and is also detrimental to cultivation as well as causing siltation of water bodies, resulting in the abandonment of many irrigation tanks adjoining the kan lands.

Expressing deep concern on such dismal state of affairs, at a time when forest conservation is of paramount need, the Vriksha-Laksha Andolan, Sagar and the Western Ghat Task Force of the Government of Karnataka assigned us with the task of making a rapid study of two of the kan forests, the Kurnimakki-Halmahishikan and Kullundikan in the Thirthahalli taluk of Shimoga district, which are facing severe threats from rampant allotments of large areas to private parties for non-forestry purposes and from conflicting claims of ownership, with the forest department not enjoying adequate power to save these kans from liquidation of their natural vegetation.

The study in the Kurnimakki-Halmahishi kan of about 1000 ha reveals the vegetation of the kan, though heavily fragmented, due to ever increasing human impacts, nevertheless, is a mosaic of various kinds of forests. The most significant is the discovery of swampy areas within this kan which have few individuals of large sized threatened tree species Syzygium travancoricum, classified in the IUCN Red List as “Critically Endangered”. The tree is on the verge of extinction, and for the Shimoga district, the only occurrence of this tree is the Kurnimakki-Halmahishi kan.

The Kullundikan of about 453 ha has a narrow belt of original tropical rainforest dominated by the tree Dipterocarpus indicus, considered ‘Endangered’by the IUCN. The revenue department in control of this kan, being totally ignorant of its vegetation richness has made several grants within the kan for cultivation of coffee and arecanut. The grantees have also done encroachments within this climax forest area of high watershed value. The cutting of the climax forest for raising coffee or any other crop is totally unjustified.

We therefore recommend that the Government of Karnataka take immediate action to arrest the degradation of kan forests on priority basis by:

-

Proper survey and mapping of boundaries of all kans;

-

Assign the kan forests to the Forest Department for conservation and sustainable management;

-

Constituting Village Forest Committees for facilitating joint forest management of the kan forests;

-

Taking speedy action on eviction of encroachers from the kans;

-

Giving proper importance to the watershed value and biodiversity of the kans;

-

Taking special care of threatened species and threatened micro-habitats within the kans;

-

Heritage sites status to ‘kans’ under section 37(1) of Biological Diversity Act 2002, Government of India as the study affirms that kans arethe repository of biological wealth of rare kind, and the need for adoption of holistic eco-system management for conservation of particularly the rare and endemic flora of the Western Ghats. The premium should be on conservation of the remaining evergreen and semi-evergreen forests, which are vital for the water security (perenniality of streams) and food security (sustenance of biodiversity). There still exists a chance to restore the lost natural evergreen to semi-evergreen forests through appropriate conservation and management practices.

TRAGEDY OF THE KAN SACRED FORESTS OF SHIMOGA DISTRICT: NEED FOR URGENT POLICY INTERVENTIONS FOR CONSERVATION

(CASE STUDIES OF KURNIMAKKI-HALMAHISHI AND KULLUNDI KANS OF THIRTHAHALLI TALUK)

- INTRODUCTION

Most human societies, in the course of millennia of social and cultural evolution, had evolved a variety of regulatory measures to ensure sustainable utilization of natural resources. These measures included family-wise restricted quota of forest biomass, removal of only dead and fallen plants, sharing of natural resources, prohibition on sale of forest biomass to outsiders (all of which are to this day followed in the Halkar village in the outskirts of Kumta town in Uttara Kannada district). The fishing families in the estuarine villages in the Kumta taluk of Aghanashini River had shared among them traditional fishing privileges in the individual ‘kodis’ or estuarine channels. Traditional hunting was a taboo until Deepavali festival in the forested villages of Uttara Kannada. To quote Madhav Gadgil (1992):

For local people, degradation of natural resources is a genuine hardship, and of all the people and groups who compose the Indian society they are the most likely to be motivated to take good care of the landscape and ecosystems on which they depend. The many traditions of nature conservation that are still practiced could form a basis for a viable strategy of biodiversity conservation.

Protection of forest patches as sacred has been reported from many parts of India and many other countries in the recent decades. Trees were normally not to be cut in such forests as they were dedicated to gods. Such sacred groves still persist in many parts of Asia and Africa (Gadgil and Vartak, 1976; Frazer, 1935; Gadgil, 1987).

Most of Himalayas, the rain forest clad North East India, the Central Indian hills, parts of Rajaputana region, many parts of Deccan and the Western Ghat-west coast regions of India had witnessed through ages the strong tradition of conservation of patches of forests as sacred, especially by village and forest dwelling communities. During the period of British colonialism the government asserted its ownership over common lands, including sacred forests, which the local communities had safeguarded and managed through generations. Sweeping cultural changes concomitant with industrial and agricultural advancements also changed traditional belief systems in which nature had a central role. Worship of gods associated with natural sacred sites and ‘panchabhutas’ or the five elements, has in a major scale given way to installing deities in man-made structures, causing neglect and even exploitation of the precious heritage of natural sacred sites. Nevertheless, Malhotra et al. (2001) have made an excellent compilation from the states like Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Chattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jarkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Orissa, western Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Tripura, Uttaranchal etc., which have more forest wealth than other states, strong evidences of nature conservation tradition, in the form of sacred groves. These sacred forests are known by various names in peninsular India: such as devarakadu, devarubana or kan in Karnataka, kavu in Kerala, kovilkadu in Tamil Nadu and devrai in Maharashtra.

D. Brandis (1897), the first Inspector General of Forests in India, was one of the first persons to make commendation on the system of sacred groves in the country:

Very little has been published regarding sacred groves in India, but they are, or rather were, very numerous. I have found them nearly in all provinces. As instances I may mention the Garo and Khasi hills which I visited in 1879, the Devarakadus or sacred groves of Coorg….and the hill ranges of the Salem district in the Madras Presidency….These are situated in the moister parts of the country. In the dry region sacred groves are particularly numerous in Rajputana. In Mewar, they usually consist of Anogeissus latifolia, a moderate sized tree with small leaves, which fall early in the dry season….Before falling the foliage of these trees turns a beautiful yellowish red, and at that season these woods resemble our beech forests in the autumn. In the southernmost States of Rajaputana, in Partabgarh and Banswara, in a somewhat moister climate, the sacred groves, here called Malwan, consists of a variety of trees….These sacred forests, as a rule, are never touched by the axe, except when wood is wanted for the repair of religious buildings

Brandis also referred to a “ remarkable little forest of Sal (Shorea robusta)” near Gorakhpur being maintained by a Muslim saint, Mian Sahib. The forest was in good condition and well protected. Nothing was allowed to be cut except wood to feed the sacred fire and “this required the cutting annually of a small number of trees which were carefully selected among those that showed signs of age and decay.”

- KANS AS SACRED GROVES

Francis Buchanan (1870): Alluding obviously to the system of sacredness of forests in the Western Ghats-west coast of Uttara Kannada, Dr. Francis Buchanan, officer of the British East India Company, who travelled through Uttara Kannada in 1801, soon after capturing Canara region by the British stated:

The forests are the property of the gods of the village in which they are situated, and the trees ought not to be cut without having leave from the Gauda (headman of the village)…. who here also is pujari (priest) to the temple of the village god. The idol receives nothing for granting this permission; but the neglect of the ceremony of asking his leave brings his vengeance on the guilty person.

Buchanan (1870 continued further: “Each village has a different god, some male, some female, but by the Brahmins they are called Saktis, as requiring bloody sacrifices to their appease their wrath”

From these statements may be inferred that the forests were virtually under the control of the village communities with well defined territories and many had sacred values attributed to them. Buchanan’s references to the then practice of slashing and burning of forests in the hills for shifting cultivation, indicates the fact that all forests were not sacred, and the sacred forests also bore the name kan or kanu.

W.A. Talbot (1909): In his monumental floristic work Forest Flora of the Bombay Presidency and Sind Talbot referred to the sacredness of kans, a rare such remark from a British officer:

In North Kanara and even as far east as the Hangal subdivision of the Dharwar district along the Western Ghats under an annual rainfall of not less than 70”, isolated irregularly distributed patches of rain-forest, locally called Kans and Rais are found surrounded by cultivation or monsoon-forest. These are often the mere remnant of larger areas and have in many instances been respected by the natives as the abode of a sylvan deity.

Talbot’s statement makes it clear that even towards the drier east of Uttara Kannada district bordering the Hangal taluk, with rainfall much lower, compared to the mountainous malnadu part of Western Ghats, there existed evergreen forests equivalent to rain forests, the kans, which were home to village deities. These kans were already on the decline as they were mere “remnant of larger areas.”

The special protection given to the kans by the village communities of Sorab in Shimoga district had won full praise from Peter Ashton (1988), renown tropical forest ecologist, who considered kans as:

Prototypes of a technique currently being promoted as a new approach to forestry: agroforestry. In a region dominated by deciduous forests (Sorab is bordering on the drier Deccan Plateau) that were annually burned, the kans stood out as belts, often miles long, of evergreen forest along the moist scrap of the Western Ghat hills. Assiduously protected by the villagers, these once natural forests had been enriched by the inhabitants through interplanting of jackfruits, sago and sugar palms, pepper vine, and even coffee, an exotic.

Ashton (1988) justifies such kind of conservation in India seeking an explanation in its culture:

The Indian sub-continent is without doubt the world centre of human cultural diversity… The Hindus have inherited perceptions of a people who have lived since ancient times in a humid climate particularly favourable for forest life. Settled people, they see themselves as one with the natural world, as both custodians and dependents…. Forests of the mountains and watersheds have been traditionally been sacred; springs and the natural landscape in their vicinity have attracted special veneration. The Hindus learned from their predecessors millennia ago, a mythology, sociology and technology of irrigation that has enabled the most intensive yet sustainable agriculture humanity has so far devised.

In the above remarks, Ashton was referring to culture based conservation in India, and how the veneration of watershed forests in the highlands facilitated “most intensive yet sustainable agriculture humanity has so far devised.”

Area under the kans

It is difficult to get a consolidated account of the area under the kans, at the time of the establishment of British authority over the forest resources of the malnadu regions of Karnataka. It appears that survey and demarcation of the kans was an incomplete work. Several kans of Uttara Kannada district got merged with rest of the state reserved forests and lost their special identities. They are to be recognized today by their names, such as Kathalekan, Karikan, Hulidevarukan etc. and also by the relics of primeval vegetation that still might be persisting in them to some degrees. According to the earliest ever survey on the kans conducted by Brandis and Grant (1868), Sorab taluk of Shimoga district had 171 kans covering a total of 32,594 acres (about 13,000 ha). Halesorabkan, the largest of them covered an area of about 400 ha. The kans were different from the secondary forests of deciduous kinds. Such systematic documentation of kans was not conducted elsewhere. Cowlidurg (present Thirthahalli taluk) was leading in the number of kans (436); Kadur district (present Chikmagalur) had 128 kans (Brandis and Grant, 1868).

The Gazetteer of Mysore: Shimoga District (1920) merely refers to the kans as evergreen forests of not much value, at a time when the hardwood timber yielding deciduous forests were paid much more attention. The Gazetteer states on the kans of Sagar taluk:

Excepting the great Hinni forest, which lies to the south of the Gersoppa Falls, the remainder are chiefly kans, or tracts of virgin evergreen forest, in most of which pepper grows abundantly self-sown and uncared for, but little of the produce being collected owing to the depredations of the monkeys.

The Gazetteer considers the kans towards the summits of ghats as not of much use owing to inaccessibility. It admits to the decline of kans; yet had much in praise for the kans of Sorab:

The taluk of Sorab abounds with kans, many of which are cultivated with pepper vines and sometimes coffee. The sago palm(Caryota urens) is also much grown for the sake of its toddy. These kans are apparently the remains of the old forests, which appear once to have stretched as far east as Anavatti. At the present day at Anavatti itself there is no wood, and the surrounding country is clothed with either scrub jungle or small deciduous forest….Kans are found also in Sagar, Nagar and other Malnad taluks, but those in Sorab are, from their number, situation and accessibility the most valuable.

- ROLE OF KAN FORESTS IN PRE-COLONIAL LAND USE SYSTEM

- Kans as sacred groves: While they acted as decentralized, community-based system of biodiversity conservation, these specially preserved forest patches played major roles as important centres of local religion and culture. They, with or without any man-built structures, functioned as abodes of village deities. Today most kans are under state ownership; nevertheless their roles continue as centres of worship, as far as the local communities are concerned. When we surveyed the kans of 10 villages of Sirsi taluk, which were included in a forest working plan for firewood supply to Sirsi town (Thippeswami, 1963), all of them were associated with sacred spots with deities, where people gathered and worshipped, despite state ownership over the forests. Such is the case with most other kans elsewhere too, in which matter, they are comparable to the devarakadus of Coorg. Whereas the latter got recognition from the State as sacred forests, and community rights were honoured, the same did not happen in Uttara Kannada and Shimoga districts. Whereas ownership on the former were claimed by the forest department of the Government of Bombay, the kans of Shimoga, in the erstwhile kingdom of Mysore district, came under the jurisdiction of either the forest or revenue departments, under the overlordship of the British, after the defeat of Tippu Sultan in 1799.

Timber felling was a taboo in the kans ensuring their preservation through ages as in the devarakadus of Coorg, devrais of Maharashtra and kavus of Kerala. The deities of most kans belong to the folk tradition of India and not to the Vedic tradition. To name a few from Karnataka malnadu are Choudamma, Rachamma, Jataka, Birappa, Bhutappa, Hulidevaru (tiger deity) etc. Occasionally are smaller groves called naagarabanas dedicated to the serpents.

- Kans as safety forests: The kan forests, well preserved in pre-colonial landuse system, in many ways ensured safety and integrity of the rural landscapes of Western Ghats. From a landscape ecological point of view these in tact forest patches formed a mosaic with other elements such as secondary forests, scrub, shifting cultivation fallows, grasslands, farms and water bodies to enhance landscape heterogeneity holding highest amount of species diversity. As safety forests they performed the following functions as well:

- Watershed protection: The kans are often found to be associated with water sources like springs or ponds. The Government of Bombay (1923) highlighted the watershed value of the kans of Uttara Kannada:

Throughout the area, both in Sirsi and Siddapur, there are few tanks and few deep wells and the people depend much on springs …. If a heavy evergreen forest is felled in the dry season the flow of water from any spring it feeds increases rapidly though no rainwater may have fallen for some months.

-

Keeping favourable microclimate: Wingate (1888), the forest settlement officer for Uttara Kannada noted that the kans were of great economic and climatic importance as they favoured the existence of springs, and perennial streams, and generally indicated the proximity of valuable spice gardens, which derived from them both shade and moisture- a scenario, that holds good to this day if the kan is good state.

-

Kans for fire protection: Brandis and Grant (1868), in their report on the kans of Sorab observed that during dry months jungle fires swept through every part of the dry forest which was composed of deciduous trees and bamboo. But, “No fires enter the evergreen forest, leaves, branches and fallen trees accumulate and gradually decay, forming ultimately a rich surface layer of vegetable mould.” Not aware of the village communities’ stakes in preservation of these kan safety forests, Brandis and Grant wondered: “why a certain locality should be covered with evergreen, and another in its immediate vicinity with dry forest.” The degradation of evergreen kans in Shimoga district has increased from the rising threats from forest fires in the recent years.

-

Protection from soil erosion: Rain forests are considered fragile places, their collapse in highlands and slopes often associated with soil erosion, compaction and rockiness. The kans -understood as heavy evergreen forests, the ground covered with “a rich surface layer of vegetable mould” (Brandis and Grant, 1868) with very sharply defined limits, alternating with bare grounds covered with laterite was a common spectacle of malnadu area. “The real cause of this alternation of bare ground and densely wooded patches is to be found in the laterite formation. Wherever the hard bed of laterite is near the surface, wood refuses to grow” (Gazetteer of Mysore-Shimoga, 1920). Further “In the kans the soil is rich and deep, but in most of the taluks (of Shimoga) the soil is hard and shallow, with much laterite” (-ibid-).

-

Kans for subsistence: Despite grain crops and gardens, the malnadu people lived at subsistence level, with much dependence on forests. Dependence on kans was mainly for wild pepper, cinnamon (both were traded commodities), edible fruits and seeds, medicinal plants, toddy and palm sugar from Caryota palm (bainy) etc. Combined with a regulated form of hunting the common people, by and large, lived in harmony with the rain forests. The landscape heterogeneity of grasslands and forests (including the well preserved kans) would have favoured rich wildlife and many people hunted for subsistence. The kans would act as buffers especially during times of drought and famines by providing not only water but also various kinds of food from the wild.

-

Biodiversity conservation: Kans ranging in size from part of an hectare to few hundred hectares each and protected from time immemorial, may be considered as the best samples of climax forests of the region. These sacred groves often served as good refuges for arboreal birds and mammals, especially primates, and many other denizens of deep forests. Thus Kathalekan in Siddapur taluk of Uttara Kannada is home to the rare rain forest habitat called Myristica swamps with their threatened flora that include Myristica magnifica, Gymnacranthera canarica, Dipterocarpus indicus, Semecarpus kathalekanensis, Syzygium travancoricum etc. Karikan in the Honavar taluk of Uttara Kannada has a rare and magnificent stand of the climax forest tree D. indicus. S. travancoricum survives today in Mathigar kanand in Aralihonda of Siddapur, which are sacred groves, small fragments of around one hectare each, in the midst of otherwise an agricultural landscape. When a 2.5 sq. km area of Kathalekan was surveyed about 35 species of frogs and their relatives were discovered there, a number that is equal to almost the entire amphibian population of Maharashtra State. Katalkean and its immediate vicinity harbor the northernmost population of the Endangered primate Lion-tailed macaque.

-

Care of pepper vines in the kans: Black pepper (Piper nigrum) was an important item of trade through the west coast port for over 2000 years (Saletore, 1973). Pepper grows wild in the wet evergreen forests of Western Ghats and is also cultivated in the gardens. A 16th century queen of Gersoppa was popularly known as ‘Pepper Queen” to the Portuguese (Campbell, 1883). From Buchanan’s writings it becomes clear that in at least in some of the kans of coastal Uttara Kannada the villagers used to take care of the wild pepper. Buchanan understood these as ‘myanasu canu’ meaning ‘menasu kanu’ or kans with black pepper. Wild pepper required human attention for better yield. Such kans with lofty evergreen trees were seen in the otherwise much denuded coastal hills. The practice of tending to wild pepper in the kans may be older to pepper cultivation in the arecanut gardens (Chandran and Gadgil, 1993). The amount of pepper produced from kans, at one time was said to be “very great”.

- Land tenure: The village communities of Karnataka malndu enjoyed various kinds of forest privileges in the pre-colonial times. They had as such no rights to claim forest lands as their own. The kans were entered in the revenue records as assessed lands held in regular tenure by wargdars or landholders in the vicinity. These wargdars paid certain taxes or warg to the state for use of the kans (for mainly collection of non-wood produce). Some of the kans of Sorab were ‘unoccupied’ and yielded no revenue at the time of the survey by Brandis and Grant (1868). They were deserted because of higher taxation by the state, thereby implying that the ownership of kans was vested with the state despite the people enjoying traditional privileges. Usually the kans had distinct boundaries marked by old trenches or footpaths. Each holder or wargdar had a portion demarcated by some lines or footpaths or other identification marks. Captain Someren (1871) found several unoccupied kans in the Belandur area of Shimoga.

- DECLINE OF THE KANS

State domination over the forests, beginning in the British period in early 19th century, resulted in the villagers losing their hold over forests, including the kans. Following the Indian Forest Act of 1878 the kans of Uttara Kannada were mostly brought under the state reserved forests. People’s rights in the kans of Uttara Kannada were curtailed to certain minor concessions like collection of dry fuelwood as in eastern parts of Sirsi and Siddapur (Government of Bombay, 1923). The kans of Shimoga district in the Mysore kingdom came under the jurisdiction of the forest department or revenue department.

-

Introduction of contract system: Contract system was introduced in the kans of Uttara Kannada for collection of non-timber forest produce. The contractors used to extract products like pepper and cinnamon in a destructive fashion, cutting down the pepper vines to collect their produce and hacking down the cinnamon trees for the bark, as for example in Kallabbe kan of Kumta (Wingate, 1888).

-

Kans for meeting timber and fuel needs: Tree cutting in the kans, as in any other sacred forests, was considered a taboo. In Uttara Kannada, following forest reservation, communities lost their traditional hold over forests. Though degraded forests around densely populated villages and towns were set aside as ‘minor forests’ for extraction of especially fuel and leaf manure, as the earlier community centred management system had collapsed, there was rising pressure on these minor forests, leading to their rapid degradation. Yielding to such demand from local people for forest biomass, in eastern Sirsi and Siddapur, villagers were allowed to gather firewood from the kans, which hitherto, the local communities had preserved as sacred places. Collins (1922) reported that in eastern Sirsi and Siddapur the kans were getting infested with the shrubby weed Lantana because of forest degradation. Similar was the situation regarding the kans of Shimoga. Resource shortage faced by the common people after reservations, especially of the timber rich forests, prompted people to fell trees in the kans of Shimoga. According to M.S.N. Rao, a forest officer (1919) fellings in the kans of Shimoga had disastrous effects, including the disappearance of the water supply. Today we can see scores of canopy gaps in these kans, periodical fires burning annually drier patches of woods, inviting once again more deciduous vegetation and bamboo which have become potential fire hazards in otherwise evergreen forests. As the kans were getting exposed to more intense sunlight through wider canopy gaps many have turned too dry for pepper-vines, which was once a major product from the kans, and a priced commodity for international trade from the dawn of history.

-

Logging in the kans: During 1940’s Dipterocarpus indicus from Kathalekan in Uttara Kannada was supplied to the railways and a plywood company. A forest working plan of 1966 for Sirsi and Siddapur taluks included 4,000 ha of kans for felling of industrial timbers (Shanmukhappa, 1966). Another working plan for Sirsi included 670 ha of kans for selection of firewood species for Sirsi town supply (Thippeswami, 1963). Menasikan of Siddapur was clear-felled and converted into forest monoculture plantation (Chandran and Gadgil, 1993).

-

Pressure from developmental processes: Towns and villages are expanding into even the kan areas. For eg. In the neighborhood of Sorab a major road is passing through Gundsettykoppakan. The Sorab town itself has expanded into Hiresekunikan of 20 ha.

-

Kans turn into coffee estates: Coffee introduced into the kans of Chikmagalur district apparently made at least some of the local Wargadars into estate owners. Because of the Revenue Department ownership of many of the kans in Shimoga district, lands within these kans were indiscriminately allotted for coffee cultivation, ignoring their ecological significance, sacredness, and village community based management systems. The Forest Department of Shimoga is making fervent efforts to salvage 90 acres of kan granted to five persons from Survey no. 27 and 52 acres of kan land from Survey no. 29 (both from Kullunde kan of Tirthahalli taluk) granted to three persons for coffee cultivation. Such things have taken place throughout the kans of Shimoga district.

-

Encroachment of kans: Kan encroachment in large-scale, especially for cultivation, is widespread throughout Shimoga district. In Uttara Kannada district even Myristica swamps associated with some of the kans were not spared by encroachers.

Contract system in the kans: The state takeover of kans was followed by the introduction of contract system for collection of non-wood produce. The impact in Uttara Kannada, on account of this may be described in the words of Wingate (1888), the forest settlement officer:

I am still of the opinion that the system of annually selling by auction the produce of the kans is a pernicious one. The contractor sends forth his subordinates and coolies, who hack about the kans just as they please, the pepper vines are cut down from the root, dragged from the trees and the fruits then gathered, while the cinnamon trees are all but destroyed…. I was greatly struck with the general destruction of the Kumta evergreens, they were in a far finer state of preservation 15 years ago.

-

Kan allotment for leaf manure and conversion into minor forests: Collins (1922) pointed out that as a variation from its policy of strict protection of kans the Government of Bombay allotted them in any villages of Sirsi and Siddapur taluks to arecanut farmers as betta or leaf manure forests. In eastern Sirsi 769 hectares of kans were added to the minor forests open for exploitation. In Shimoga district several privileges were conceded to the local peoples inside the kans, also leading to their degradation. In Sorab and rest of Shimoga as the timber rich deciduous forests were taken over by the Government as state reserved forests the people were given certain concessions, including fuelwood harvests from kans, which they had conserved through ages as sacred forests. In Uttara Kannada kans (after British domination of the district from 1799, over a period of next 50 years or so, the British consolidated their hold over the forests) contract system was introduced for collection of non-timber forest produce from the kans. This system obviously replaced the system of people’s management that prevailed earlier. The contractor, being interested more in making short term profits, often resorted to destructive harvest of non-timber forest produce from the kans.

8.1 CASE STUDIES ON TWO KAN FORESTS OF THIRTHAHALLI TALUK

- INTRODUCTION

Thirthahalli taluk (area:1254 sq.km) is situated towards the south-west of Shimoga district between lat. 13°27’22” to 13°55’27” and long. 75°01’57” to 75°30’42”. It is predominantly a hilly taluk right in the middle of central Western Ghats at a mean altitude of 603 m above the msl. Whereas most high rising hills are within 750 m, Heggargudda hill range, covered mostly by Kurnimakki-Halmahishikan, has its summit at 850 m. The taluk is rich in water courses and is drained mainly by the Tunga River and its smaller tributaries and streams. Most of the forest clad hills are associated with such water courses which along their passages through narrow valleys irrigate rice fields and arecanut gardens. The hill ranges of Thirthahalli, which also include the Agumbe Ghat, famed as one of the highest rainfall areas of India, much of it was clad in extremely rich rain forests of central Western Ghats is, is at the heart of the watershed for good part of Karnataka because of the Tunga-Bhadra River. The taluk, as per 2001 Census, had a population of 143,207 persons. Majority of them (128,399 persons) residing in rural areas. The livestock population (1993 census) was quite high at 144,299.

-

Abundance of tanks and streams: Thirthahalli taluk is rich in water resources, especially in streams, compared to the drier eastern portions of Shimoga district. Numerous streams which originate in the hills of the taluk rush through rugged terrain before entering narrow valleys cultivated with gardens and rice fields. The Tunga River that winds its way through in between hills receives most of these streams. In addition there are 741 tanks, most of them built along the stream courses generations back. Gross area irrigated by the tanks in the taluk amounts to 7328 ha, and net irrigated area is 6911 ha. Net area irrigated in the taluk, from all sources, is 11537 ha which highlights the richness of water resources.

-

Rainfall: Thirthahalli, is one of the rainiest taluks in Shimoga district. Agumbe towards the south-west of Thirthahalli is one of the rainiest places in India. The taluk has a normal average rainfall of 3042 mm/yr. It received 2938 mm of rainfall during 2010-11, as shown in the Table: 1

Table 1: Actual and normal rainfall in Thirthahalli taluk for 2010-11

| Months |

Actual monthly rainfall –mm |

Normal monthly rainfall-mm |

| January |

1 |

6 |

| February |

2 |

0 |

| March |

5 |

7 |

| April |

35 |

37 |

| May |

100 |

62 |

| June |

562 |

521 |

| July |

1119 |

890 |

| August |

728 |

866 |

| September |

196 |

338 |

| October |

140 |

169 |

| November |

41 |

146 |

| December |

9 |

0 |

| Total |

2938 |

3042 |

-

Cultivation: Total cropped area in the taluk, in the year 2010-2011 was 25,879 ha, approximately about 20% of the total area of the taluk. Most details on area under various notable crops are given in the Table 2. Paddy occupies most of the cultivable land. Arecanut, coconut, banana, sapota, pepper, cardamom and cashew are the notable horticultural crops. Details regarding the output of various important crops are given in the Table 3.

Table 2: Area under various crops in 2010-11

| Crops |

Area (ha) |

| Foodgrains (mainly paddy and just 3 ha of maize) |

13820 |

| Sugarcane |

54 |

| Fruit crops |

1209 |

| Pulses |

53 |

| Oil seeds |

129 |

| Horticultural crops |

1209 ha (4.67%) |

Table 3: Production details of horticultural crops (in tons) in Thirthahalli taluk

| Crops |

Production in tons |

| Banana |

16,310 |

| Mango |

210 |

| Sapota |

510 |

| Coconut |

69 lakh no. |

| Arecanut |

9338 |

| Pepper |

65 |

| Cardamom |

8 |

| Cashew |

648 |

- FOREST VEGETATION

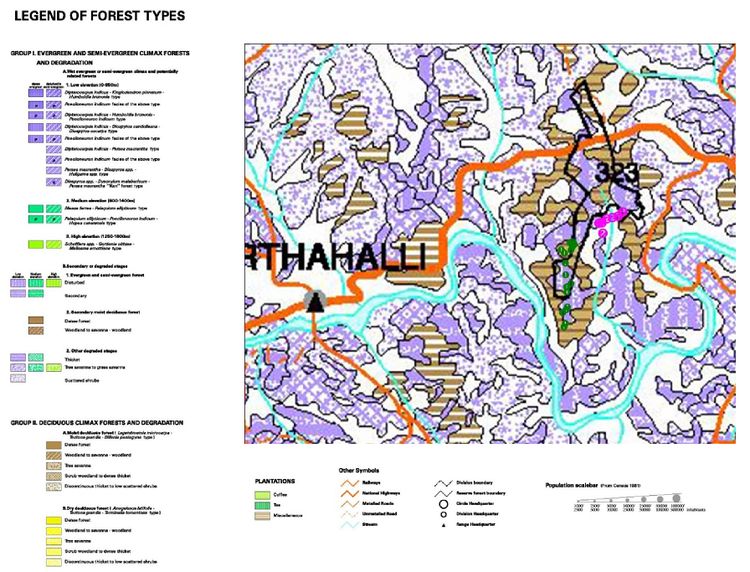

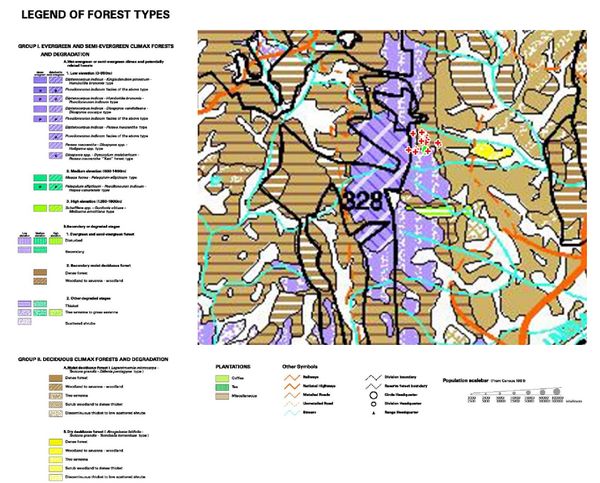

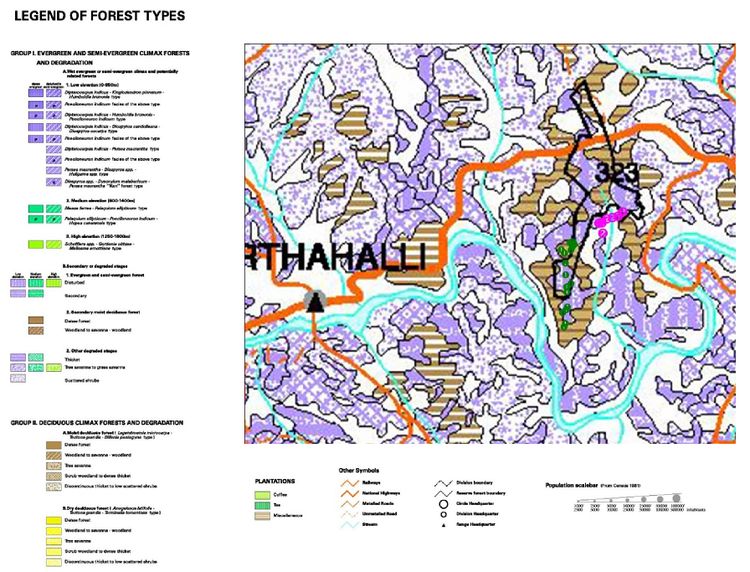

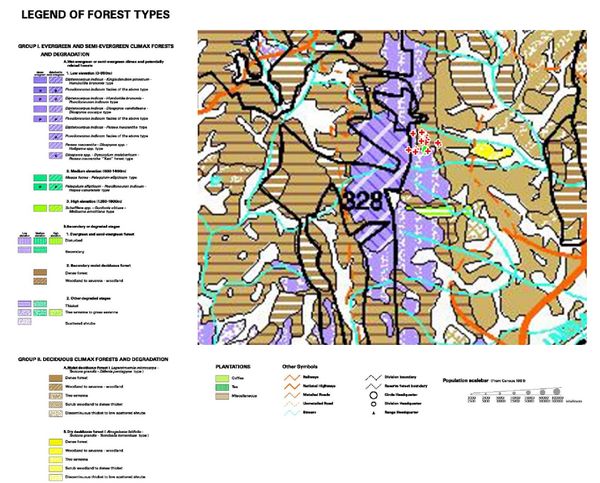

With the high rainfall in the taluk one can expect tropical evergreen forests everywhere. But actually we find mosaic of various kinds of forests. It is apparent that the original primary forests have given way to secondary forests in most places because of human impact. Pascal et al (1982) considers the main forest type of the taluk as Low elevation (disturbed) evergreen and semievergreen and their various secondary and degraded stages. More towards the east of the district, because of relatively less rugged terrain and larger cultivable areas associated with more populated villages and declining rainfall the forests are more susceptible to desiccation. Secondary moist deciduous forests form a mosaic with cultivation areas, savannas and scrub. Savanna type formations which are grassy lands with isolated trees are created by humans through fire and felling, and used for cattle grazing and meeting local biomass needs. Annual summer fires, often set on by humans, especially for burning bushes and dry litter arrests regeneration of evergreen trees in the secondary moist deciduous forests. The degraded stages of all the above types of forests in the form of scrub, isolated shrubby areas etc. are found closer to human habitations.

Case stdy-1: KURNIMAKKI-HALMAHISHIKAN

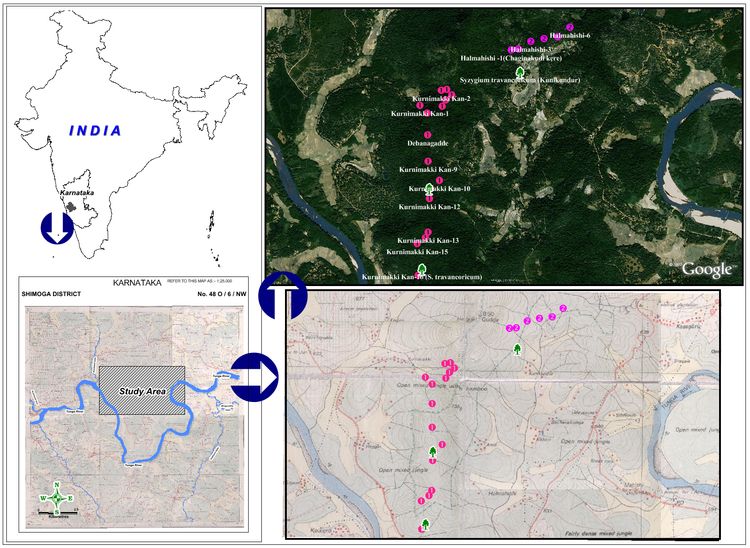

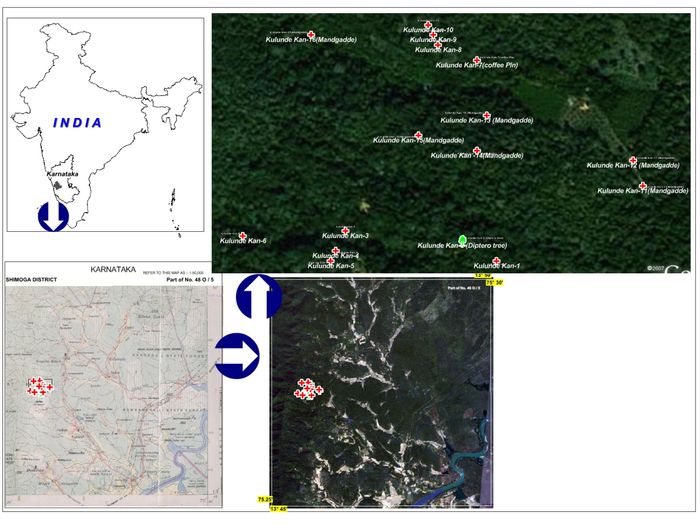

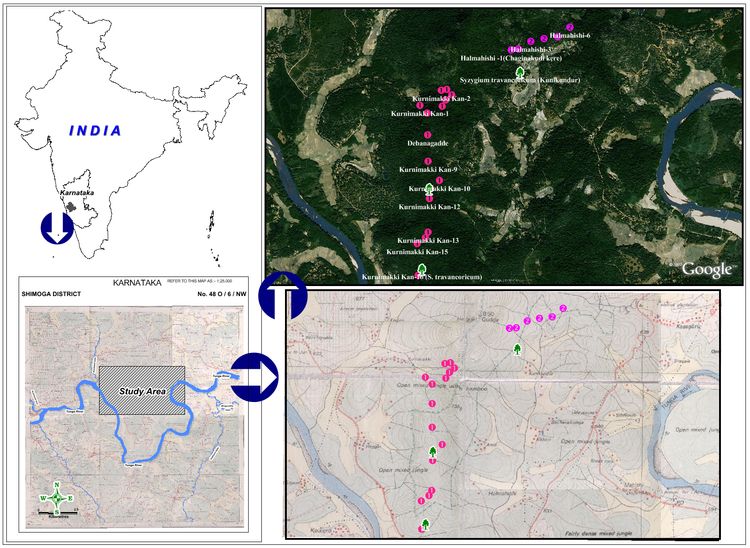

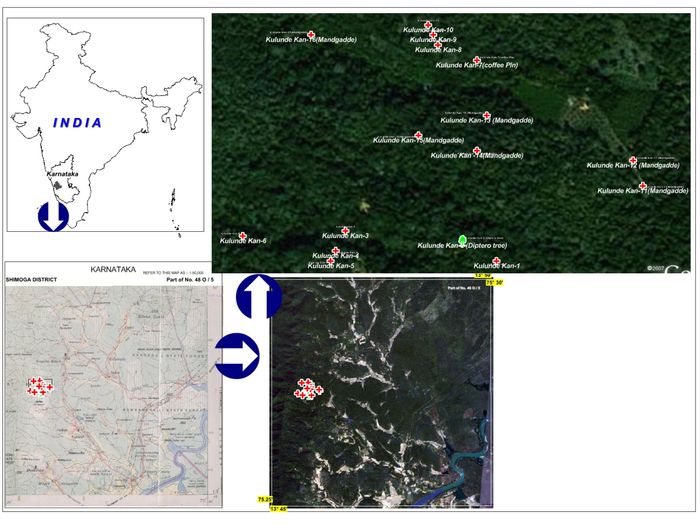

Kurnimakki-Halmahishikan (kans are known locally usually by the name of the villages adjoining them, unless there is any other recognized name) in the taluk of Thirthahalli in Shimoga district was studied in the month of April, 2012, mainly from the vegetational angle and for cognizance of threats facing it. The kan is said to be about 1000 hectares and situated between lat. 13.68°-13.73°N and 75.29°-75.35°E. It is not in a single piece but distributed in several survey nos. There is considerable confusion on the demarcation of the boundaries of the kan due to encroachments, conflicting claims of ownership and other practical problems. Looking at all the ancient maps available the kan boundaries need to be more precisely demarcated. Shimoga and Chikmagalur districts were part of erstwhile Mysore State. Kan lands were recognised by the State Forest Department till almost 1970. But after that those survey numbers were merged in Reserved Forests and other kinds of forests including Minor Forests, State forests and District forests (Gokhale et.al, undated). A Google Earth image of the kan and associated landscape elements/villages is given in the Figure 1. The study localities in Halmahishi, Bekshikenjigudda and Kesagaru villages are shown in them. Evergreen to semi-evergreen forests and secondary moist deciduous forests were the main forest types encountered. The geographical coordinates of study sites are shown in the Table 4.

Figure 1: Location, topographic, and vegetational features and forest sampling sites. The presence of Syzygium travancoricum, Critically Endangered tree in Kunikundur, Kurnimakki-10 and Kurnimakki-16. The passage of Tunga River encircling three sides of the kan is notable

Fragmentation of vegetation: The kan forests were praised in the past for their unique evergreen vegetation of lofty trees, rich, moldy soils, fire security, as source of perennial streams and production of various products in demand for human subsistence, especially as centres of pepper production, a commodity that commanded high prices worldwide. Today, a close look at the Kurnimakki-Halmahishi kan on the ground or using aerial imageries, reveal a shocking spectacle of high degree of forest fragmentation. The composition of the landscape elements of the kan does not conform to the past descriptions of such sacred forests from central Western Ghats, being today an assemblage of relics of the evergreens forming an non-cohesive mix with various degraded stages including scrub and periodically fire affected areas. It appears that many a stream originating in the kan get dried up in the summer months resulting in abandonment of the minor tanks constructed along their courses, thus obviously, with adverse consequences on farming downstream and water-flow into the Thunga River diminished. Such severe human induced changes in the evergreen forests of Western Ghats are bound to have cascading consequences on human welfare in the Deccan plains mainly because of reduced water flow in the east-flowing rivers. The condition of the forested terrain, the portion mostly falling in the erstwhile spread of the kan area, as depicted in the Forest Map of South India (Pascal et al., 1982) is shown in the Figure 2. (The legend for the map covers more kind of vegetational types than shown in the selected block)

Figure 2: Vegetation types of Kurnimakki-Halmahishi kan based on Pascal. Degradations of evergreen forests have created an assortment of patches

- Land use Land cover analysis of Select Kan forests in Shimoga

Land use land cover (LULC) information of a region depicts the status of a landscape for environmental progression and sustainable development. Land cover configuration is stated as a unified reflection of the existing natural resources, dynamic natural processes whereas land use refers to the human induced changes in the land cover. The main effects of human activities on the environment are land use and resulting land cover changes. Such changes impact the capacity of ecosystems to provide goods and services to the human society. Human induced land cover change such as for agricultural expansions have caused large scale deforestation leading to soil erosion, watershed degradation, reduced biodiversity, and agrochemical pollution. In forest dominated landscapes fragmentation issues of prominence seem to relate typically to deforestation and loss of forest cover over a period of time. Monitoring these changes isessential for sustainable management of the natural resources. It has become an essential to integrate the patterns of land cover change with the processes of land use change by identifying various drivers for the change process.

Tropical deforestation, rangeland modification, agricultural area shrink and urbanization are the major land-use and land-cover changes around the globe (Geist and Lambin, 2001). The driving force of land-use/cover change vary and their dynamic interactions result in diverse change and trajectories of change, depending upon the specific environmental, social, political and historical context from which they arise (Meyer and Tuner II, 1992). The resulting changes from these drivers exist as a complex between subtle modification and total conversion as seen in a change in forest density and forest to agricultural land or urban area (Geist and Lambin, 2001; Veldkamp and Lambin, 2001). The complexity of land use land-cover changes is illustrated by functional differences within types of land cover, structural variance between types of land-cover change, with regards to spatial arrangement and temporal pattern of change (Giest and Lambin, 2001).

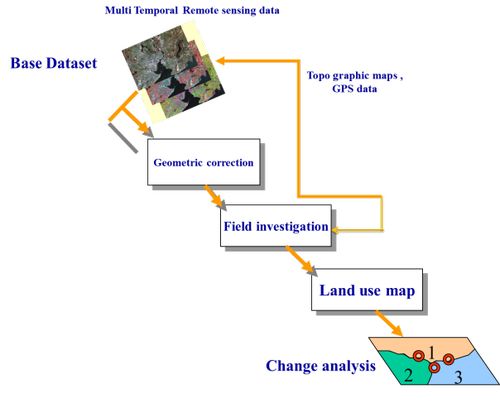

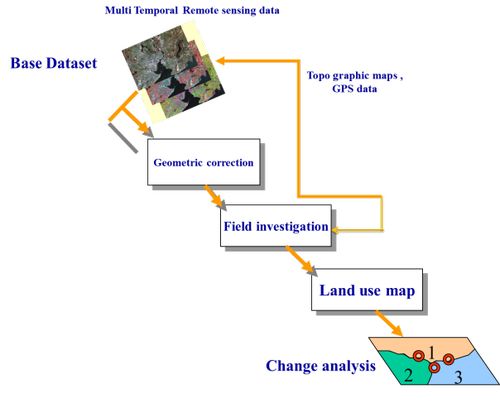

Availability of multi-resolution temporal remote sensing (RS) data has aided in monitoring larger areas at various spatial and spectral resolutions. Remote sensing data along with GIS (Geographical Information Systems), GPS (Global positioning system) and other collateral data (spatial as well as statistical) help in effective land cover analysis (Ramachandra & Kumar, 2004; Ramachandra et al., 2009). Mapping, quantifying, and monitoring the physical characteristics of land cover has been widely recognized as a key element in the study of regional and global changes (Nemani & Running, 1996). The objectives of this work is

- Classification of multi-temporal RS data to obtain LU LC map.

- Multi-temporal analysis for characterise the type and extent of fragmentation or loss of vegetation cover, Visualising the consequences of changes in the region.

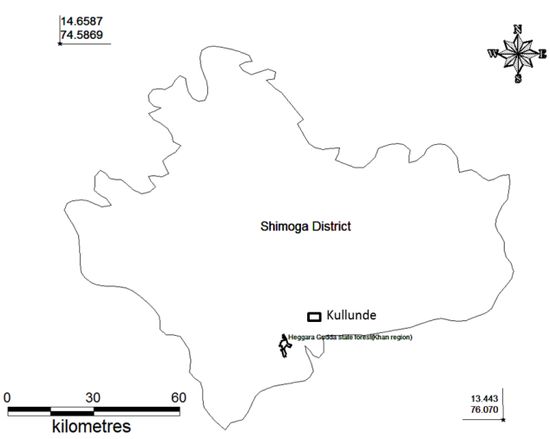

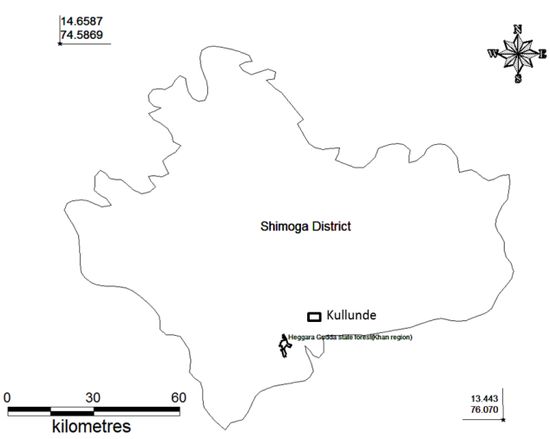

Figure 3: Shimoga district with kans

Figure 4: Halmahishi kan -Study area

Area lies between long 74.29440 Nto 75.33380 E and lat 13.74740 E to 13.71330 N in the district of Shimoga, Karnataka (state), India. This region is very near to the Tunga River and having the vegetation cover ranges from Evergreen to semi evergreen with a smaller amount of moist deciduous. The region is very rich in its biodiversity and a hot spot for high endemism. The agriculture and coffee estates are the main drivers for the deforestation in the region. The region covers Kudamalgi, Chicksangudi, Muttur, Dabbangadde, Halmahishi viilages of Thirthahalli taluk. Remote sensing (RS) data used in the study include Landsat TM (1989), IRS (2001, 2010), and Google Earth (http://earth.google.com). The Landsat data is cost effective, with high spatial resolution and freely downloadable from public domains like Glcf (http://glcfapp.glcf.umd.edu:8080/esdi/index.jsp) and USGS (http://glovis.usgs.gov/). The summery characteristics of datasets used in the current study are summarized in Table 4. Besides remote sensing data, many other data sources were used in the study. Topographic maps provided ground control points to rectify remotely sensed images and scanned paper maps.

Table 4: Data used in the study

| Data |

Sensor |

Year |

Resolution (M) |

| Landsat |

TM |

1989 |

28.5 |

| IRS |

Lis3 |

2001 |

23 |

| IRS |

Lis4 |

2010 |

5 |

Figure 5 explains the method adopted for land cover and land use analysis. The RS data of different sensors of Landsat and IRS satellites were acquired. The remote sensing data requires the preprocessing stages like atmospheric correction and geo correction in order to enable correct area measurements. Geometric correction is done by using ground control points collected from field study and Landsat data is resampled to 30 meters. The resampling is required because of the dissimilar spatial resolutions of Landsat sensors. The field investigation is carried out for intensive ground-truth studies during pre-monsoon and post-monsoon seasons. The geographic coordinates of a land cover classes are determined by using GARMIN Global Position Systems (GPS), which provides an advantageous (Zhao et al., 2003). To obtain historical land-cover data, interviewees and group discussions are conducted with farmers and forest officials at different locations in the study region.

Figure 5: Land cover and land use analysis - method

Land cover analysis was done using NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index). Calculation of NDVI for Multi-temporal data is advantageous in areas where vegetation changes rapidly. Among all techniques of land cover mapping NDVI is most widely accepted and applied (Weismiller et al., 1977, Roy et al., 2002; Ramachandra et al., 2009). NDVI for a given pixel always result in a number that ranges from minus one (-1) to plus one (+1).

NDVI was calculated using Eq. (1)

NDVI = (NIR-R) / (NIR+R) … (1)

Land use analysis was done using supervised classification scheme with selected training sites. Maximum Likelihood algorithm is a common, appropriate and efficient method in supervised classification techniques by using availability of multi-temporal “ground truth” information to obtain a suitable training set for classifier learning. GRASS GIS (Geographical Analysis Support System)software is used for the analysis, which is a free and open source software having the robust support for processing both vector and raster files accessible at http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/grass/index.php. An accuracy assessment is done to assess the quality of the information derived from remotely sensed data by a set of reference pixels. These test samples are then used to generate the error matrix (also referred as confusion matrix) kappa (κ) statistics and producer's (PA) and user's accuracies (UA) to assess the classification accuracies. Accuracy assessment and kappa statistics are included in table 7.

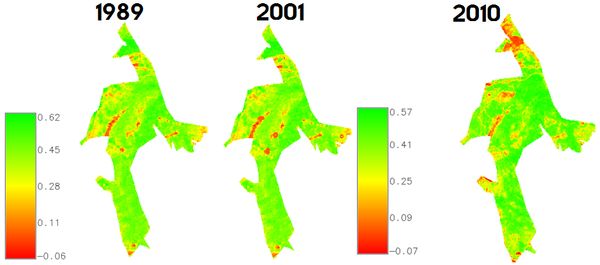

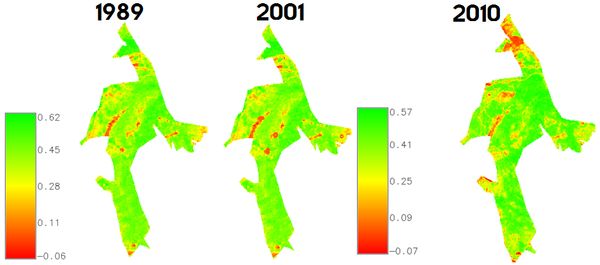

Results: Land cover analysis was done by computing Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) NDVI is based on the principle of spectral difference based on strong vegetation absorbance in the red and strong reflectance in the near-infrared part of the spectrum. Vegetation index differencing technique was used to analyze the amount of change in vegetation (green) versus non-vegetation (non-green) with the two temporal data by considering 1989 as a base. Figure 6 illustrates the land cover dynamics. The vegetation cover has decreased from 79.94 % to 69.91 % due to land encroachments for agricultural activities. Table 5 explains the land cover change with respect to each year considered in the study.

Figure 6: Land cover dynamics

Table 5: Land cover changes during 1989 to 2010

| Year |

Vegetation (%) |

Non Vegetation (%) |

| 1989 |

79.94 |

20.06 |

| 2001 |

76.75 |

23.23 |

| 2010 |

69.91 |

30.01 |

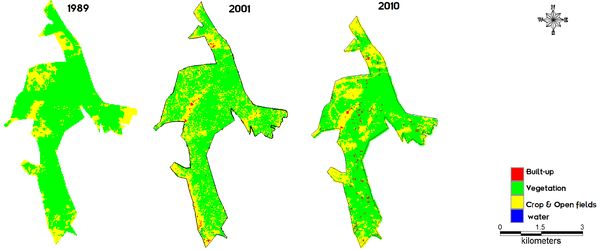

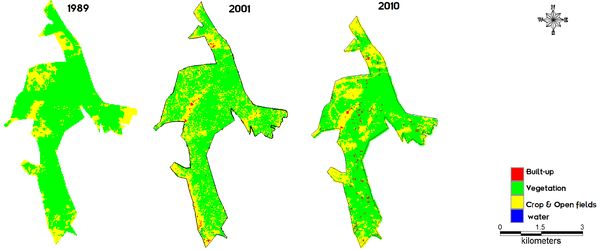

Temporal land use changes are shown in the figure 7 at landscape level from 1989 to 2010 carried out by using remote sensing data. Table 6 lists the land use changes with respect to time. The area of forest is decreased from 79.59% (1989) to 68.41% (2010), whereas agricultural land is increased from 20.41% to 29.62%. This illustrates the conversion of land for agricultural activities. The accuracy of the classification ranges from 87.38 % to 92.47% (Table 8).

Figure 7: Land use dynamics during 1989-2010

Table 6: Land use

| Year |

1989 |

2001 |

2010 |

| Category |

Ha |

% |

Ha |

% |

Ha |

% |

| Built-up |

0.00 |

0 |

20.58 |

2.09 |

20.5781 |

1.96 |

| Vegetation |

782.29 |

79.59 |

718.28 |

73.08 |

716.4776 |

68.41 |

| Water |

0.00 |

0 |

1.19 |

0.12 |

0 |

0 |

| Cropland &open fields |

200.52 |

20.41 |

242.75 |

24.71 |

245.7443 |

29.62 |

Table 7: Accuracy assessment

| Category |

1989 |

2001 |

2010 |

Overall Accuracy |

Kappa |

| PA |

UA |

PA |

UA |

PA |

UA |

| Built-up |

62.69 |

40.83 |

78.23 |

93.02 |

89.18 |

100.00 |

87.38 |

0.81 |

| Water |

99.99 |

99.86 |

98.98 |

79.49 |

91.42 |

92.44 |

91.25 |

0.86 |

| Cropland |

79.60 |

97.29 |

99.47 |

93.84 |

97.58 |

98.46 |

92.47 |

0.88 |

| Evergreen forest |

94.78 |

100.00 |

99.84 |

100.00 |

97.86 |

81.39 |

87.38 |

0.81 |

ii. Vegetation studies

Vegetation was studied in 26 sampling localities within the kan using Point-centred quarter method. The geographical coordinates of the localities sampled are shown in the Table 8.

Table 8: The localities within the kan chosen for quantitative sampling of forest

| Sl |

Localities visited |

LONGITUDE |

LATITUDE |

| 1 |

Kurnimakki Kan-1 |

75.3079 |

13.7075 |

| 2 |

Kurnimakki Kan-2 |

75.3102 |

13.7091 |

| 3 |

Kurnimakki Kan-3 |

75.3108 |

13.7092 |

| 4 |

Kurnimakki Kan-4 |

75.3113 |

13.7086 |

| 5 |

Kurnimakki kan-5 |

75.3107 |

13.7081 |

| 6 |

Kurnimakki kan-6 |

75.3103 |

13.7074 |

| 7 |

Kurnimakki kan-7 |

75.3087 |

13.7067 |

| 8 |

Kurnimakki kan-8 |

75.3107 |

13.7081 |

| 9 |

Kurnimakki Kan-9 |

75.3088 |

13.7017 |

| 10 |

Kurnimakki Kan-10 |

75.31 |

13.6997 |

| 11 |

Kurnimakki Kan-11 |

75.309 |

13.6989 |

| 12 |

Kurnimakki Kan-12 |

75.3089 |

13.6978 |

| 13 |

Kurnimakki Kan-13 |

75.3088 |

13.6943 |

| 14 |

Kurnimakki Kan-14 |

75.3085 |

13.6937 |

| 15 |

Kurnimakki Kan-15 |

75.3076 |

13.6931 |

| 16 |

Kurnimakki Kan-16 (S. travancoricum) |

75.3081 |

13.6905 |

| 17 |

Kurnimakki Kan-17 |

75.3077 |

13.6898 |

| 18 |

S. travancoricum (Wadape) |

75.3089 |

13.6989 |

| 19 |

Debanagadde |

75.3088 |

13.7044 |

| 20 |

Syzygium travancoricum (Kunikundur) |

75.3186 |

13.711 |

| 21 |

Halmahishi -1 (Chaginakudi kere) |

75.3177 |

13.7133 |

| 22 |

Halmahishi-2 |

75.3185 |

13.7134 |

| 23 |

Halmahishi-3 |

75.3198 |

13.7142 |

| 24 |

Halmahishi-4 |

75.3212 |

13.7145 |

| 25 |

Halmahishi-5 |

75.3227 |

13.7147 |

| 26 |

Halmahishi-6 |

75.324 |

13.7157 |

iii. Tree species in evergreen-semievergreen forest type

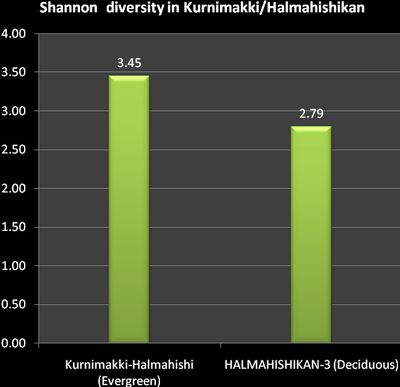

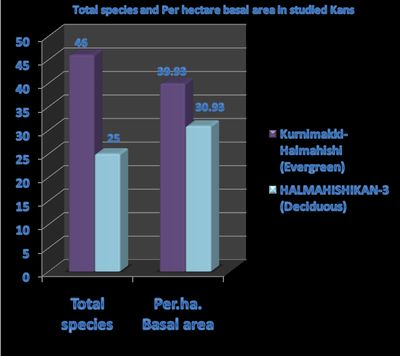

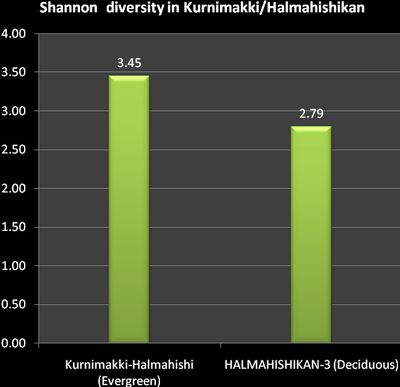

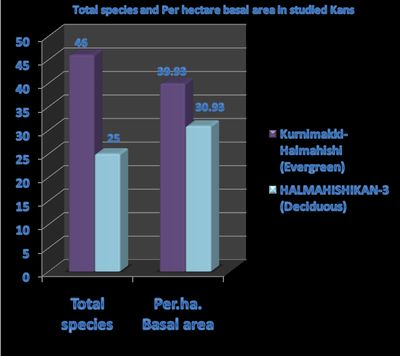

Lofty evergreen trees of 25 to 30 m height were quite many in the forest and belonged to species such as Aphanantha cuspidata, Canarium strictum (Kan: Karidhupa), Mangifera indica, Syzygium hemisphericum, S. travancoricum etc.Evergreen trees of the second level of general heights from 15-25m include Actinodaphne hookeri, Aglaia roxburghiana, Anthocephalus kadamba, Beilsmeida fagifolia, Dimocarpus longan, Ficus callosa, Holigarna ferruginea, Hopea ponga, Olea dioica, Syzygium cumini etc. Evergreen trees of still smaller stature include Aporosa lindleyana, Ixora brachiata, Knema attenuata, Litsea wightiana, Vepris bilocularis etc. We could list 46 tree species from this type of forest. Some deciduous species are also found in this type viz. Careya arboa, Lagerstroemia microcarpa, Stereospermum personatum, Terminalia paniculata, T. bellirica, Vitex altissima, Xylia xylocarpa; Zanthoxylum rhetsa, etc. The secondary deciduousforests within the kan and their peripheral areas are obviously due to forest fragmentation through cutting and burning. They have, in addition to the leaf shedding trees mentioned above also have Madhuca latifolia, Bombax ceiba, Terminalia paniculata, Firminia colorata etc. Altogether only 25 tree species were found in the deciduous forests, which include a small number of tolerant evergreens such as Olea dioica, Aporosa lindleyana, Syzygium cumini, Alstonia scholaris etc. Two patches of forests, one of evergreen remains and the second of moist deciduous kind (secondary) are shown in the Figure 8. The Shannon diversity index for trees was found to be higher (3.45) for the evergreen dominated patches than for the deciduous (2.79) (Figure 9 Shannon diversity). Details of tree species inventorised from the sample points of evergreen and deciduous areas are given in Figure 10, along with estimated basal areas/ha in both.

Figure 8: Relic evergreen forest patch and a farmland below. Water input from the kan is vital for cultivation; R. Vegetation survey in a secondary moist deciduous forest within the kan

Figure 9: Shannon diversity index for evergreen dominated and deciduous dominated areas

Figure 10: Tree species inventorised for evergreen sample points and deciduous areas and basal area estimated/ha for both.

-

Tree density/ha: The evergreen-semi-evergreen forests had more tree numbers/ha in the kan at 234/ha compared to the moist deciduous patches at 181/ha. The estimated number was lower for both types of forests than any good low elevation Western Ghat forests where the number could be >300 to 500/ha. The kan forest particularly, belonging to the traditional category of sacred forest, is expected to have more number of trees. Ever increasing human impact and conflicting claims on ownership, diluting the authority of the Forest Department, may be a pertinent factor for less than expected number of trees.

-

Basal area of trees: Basal areas of trees/ha was calculated based on the girth measurements taken for the sampled trees. The basal areawas found to be 39.93 m²/ha for evergreen/semi-evergreen areas and 30.93 m²/ha for deciduous forest areas. This lowered basal area of a sacred forest, which reflects particularly a thinning of the forest in the catchment of the Tunga River, does not augur well for hydrology of the region as a whole. The fate of the other kans in Thirthahalli taluk does not appear to be better, as the category of kan forest itself is fading away from the face of the taluk, which had once 436 kans on the record.

-

Evergreenness and endemism of trees

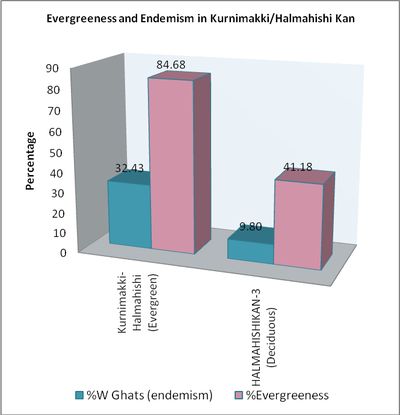

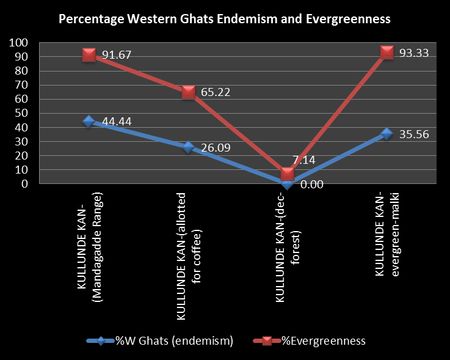

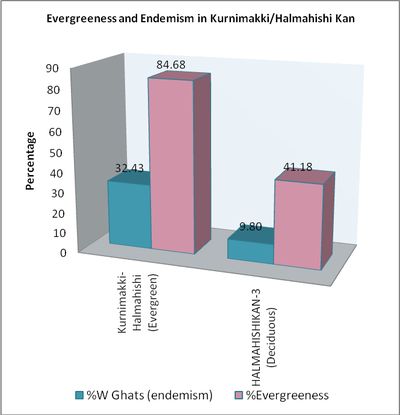

The Western Ghats, along with Sri Lanka, constitute one of the 34 Global Biodiversity, on account of high species diversity, high degree of species endemism as well as heavy human impact on the ecosystems. Endemism in any group of plant or animal is typically linked to levels of tree endemism in the forests. If there is high percentage of endemic trees in an area, endemism among lower plant groups and in the animal community is also expected to rise. The rise in percentage of Western Ghat endemism in relation to increase in percentage evergreen trees in the community is evident from the Figure 11.

Figure 11: Tree endemism in evergreen-semi-evergreen forests versus deciduous forests

Figure 12 depicts that the evergreen-semi-evergreen forest patches considered collectively for percentage of evergreen trees, showing a higher result (almost 85% individuals belonging to evergreen type) account for higher Western Ghat tree endemism (32%), compared to the predominantly deciduous patches collectively accounting for only 41% evergreenness having barely 10% endemics. Some endemics survive there because these deciduous forest patches occur in an evergreen zone of higher rainfall, and some of the desiccation and large gap tolerant trees like Lagerstroemia microcarpa (deciduous) and Taberna-montana coronaria, an understorey plant are considered endemics.One of the first casualties of gross human interference with humid forest ecosystem of the Western Ghats would be disappearance of the most sensitive endemic species. The kan forests, in the pre-colonial days would have been important local centres of plant and animal endemism, as they were considered sacred and there was strong taboo on tree cutting in such forests. Notable among the endemic trees were Calophyllum apetalum, Cinnamomum malabathrum, Holigarna arnottiana, H. ferruginea, Hopea ponga, Mastixia arborea, Polyalthia fragrans etc.

-

Swamps with Syzigium travancoricum: Tree back to life from fear of extinction: To our great surprise in some of the swampy water bodies associated with the kan we could see small populations of Syzygium travancoricum, an evergreen, endemic tree of the Western Ghats, which has been Red Listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN. Our discovery of this majestic tree in the Kurnimakki-Halmahishikan, while an altogether new report of such a species from Shimoga district itself, underscores the importance of preservation of kans as ‘Heritage Sites’ from cultural, biological angles. The tree was considered extinct from its original known home range from Travancore Western Ghats, after its first discovery by Bourdillon in 1894, as it was not observed later, probably due to its rarity. Subsequently it was rediscovered from southern Western Ghats in the early 1990’s. Its rare occurrence associated with swampy places in some of the evergreen kan forests of Ankola and Siddapur, 700 km north of Travancore came as a surprise, while this finding highlights the role of kans as centres of biodiversity conservation in otherwise human impacted landscapes (Chandran et al., 2008). As our primary objectives for the study also included bringing to light rare elements of biodiversity conserved through generations in the system of kans, we went out of way, beyond the domains of random sampling, so as to draw attention to this Critically Endangered species in its imperilled swampy habitat. Fire damages and the recent cuttings of this threatened species is a matter of grave concern (Figures 12 and 13)

Figure 12: Syzygium travancoricum close to water bodies

Figure 13: Cutting of Syzygium travancoricum in a relic primary evergreen forest patch inside the kan

-

Importance value index (IVI): The IVI of evergreen and deciduous species, listed in Table 9, show the contrast in the vegetation. Evergreens are, understandably, dominating the evergreen forest areas. Syzygium travancoricum dominated swamps were specially studied with greater efforts, because of the rarity of the species (Critically Endangered as per IUCN Red List), as already explained above. A lofty and buttressed evergreen tree species, Aphananthe cuspidata (Figure 14)has the highest IVI in the forest. The high occurrence of evergreen forest disturbance indicator and more light loving tree Aporosa lindleyana, although itself an evergreen, shows the kan forest is under stressed conditions. There are, however, several individuals of Canarium strictum (Figure 14), in the evergreen forest which is one of the good indicators of the evergreen high forest for the region.

Table 9: IVI of evergreen and deciduous species

|

Evergreen tree dominated forest patches |

Deciduous trees dominated forest patches |

| Sl |

Species |

IVI |

Species |

IVI |

| 1 |

Aphana nthe cuspidata |

47.70 |

Xylia xylocarpa |

67.99 |

| 2 |

Syzgium travancoricum |

33.57 |

Olea dioica |

35.89 |

| 5 |

Aporosa lindleyana |

14.62 |

Syzygium cumini |

30.69 |

| 3 |

Mangifera indica |

14.39 |

Term inalia bellirica |

21.40 |

| 6 |

Dimocarpus longan |

12.94 |

Alstonia scholaris |

13.20 |

| 4 |

Canarium strictum |

12.06 |

Terminalia paniculata |

11.27 |

| 8 |

Term paniculata |

10.19 |

Vitex altissima |

10.84 |

| 7 |

Hopea ponga |

9.96 |

Dimocarpus longana |

10.54 |

| 9 |

Terminalia bellirica |

9.52 |

Spondias acuminata |

10.35 |

| 10 |

Canthium dicoccum |

8.20 |

Ervatamia heyneana |

8.89 |

Figure 14: Aphananthe cuspidata and Canarium strictum, dominant evergreen species

-

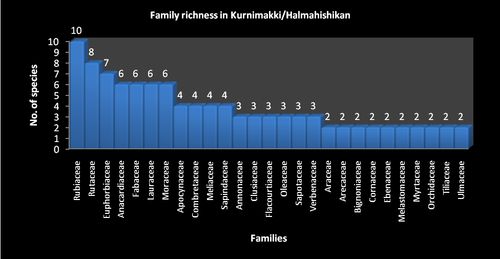

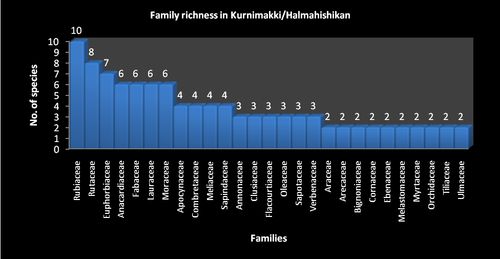

Species-richness: family-wise: The details of species numbers, family-wise, are given in the Figure 15. Rubiaceae and Rutaceae were the most specious families, followed by others. The details of species observed during the short term survey, including their geographic distribution, are given in the Annexure 1.

Figure 15: Vegetation richness in Kurnimakki/Halmahishi Kan

iV. Decline in hydrological value

The concept of kans as important watershed areas diminished in due course with major changes in the vegetation, especially, with the decline of evergreens and the entry of fire to clear portions of the kans where subsequently only deciduous woods regenerated causing exposure of rocks underneath and compacted and eroded soils. Subsequently many tanks, especially smaller ones, got silted up and their utility from irrigation point stopped. The Figures (figure 16) of a small, silted tank (which is still a refuge for several Syzygium travancoricum trees), adjoining a fire burned forest, and subsequently abandoned water canal are given here.

Figure 16: A silted water tank with dead and fallen Syzygium travancoricum (on account of fire) and an abandoned water canal within the kan

v. A sacred kan on the wane

The kan forests of central Western Ghats, were important natural sacred sites and cultural centres of the pre-British village communities. They were like similar natural sacred sites elsewhere in the Western Ghats, viz. the devrais of Maharashtra, devarakadus of Coorg or kavus of Kerala. At one time, they rose majestically in the horizons, covering large areas in the high places of the malnadu village landscapes, surrounded by cultivations, timber rich secondary forests, and savannized grazing areas. Perennial streams gushing out of these sacred forests were often embanked to make irrigation tanks. The run of numerous such streams ended with their merger with the rivers, which owed for their perennial nature to such streams which flowed even during the hot and rainless months. Unfortunately, the kans did not merit consideration as sacred places of village communities under the British rule and also after Independence. There were only stray references to the sacredness of the kans by some officers of the British regime. And as such the kans were simply viewed as dense evergreen forests important for pepper, toddy and sugar from the palm Caryota urens and for few other items of commercial or subsistence values. In Shimoga district, particularly, many kans were brought under the jurisdiction of the Revenue Department, which conveniently allotted kan lands for meeting various non-forestry purposes such as for growing coffee, expansion of cultivation, for grazing purposes and numerous others, inconsiderate and negligent of the rare species they conserved and also of their crucial hydrological importance. The Government also conceded large portions of kans on long leases to the Mysore Paper Mills for growing industrial woods like Eucalyptus and Acacia spp. after clearing the natural vegetation (Annexure 2).

Continuation of sacred sites

As far as sacredness of the Kurnimakki-Halmahishi kan is concerned we need to state that there are still several sites within the kan which are abodes of village deities; for instance, Chowdi, Siddaradevaru, Betedevaru and Nagaradevaru are names of some such deities of Kunikundur village. The abode of a deity within the kan (represented by crude stones only) is shown in the figure 17. Other villages also have their deities still associated with the kan.

Figure 17: A sacred spot within the kan, where the deity is worshipped

Case study II. KULLUNDEKAN

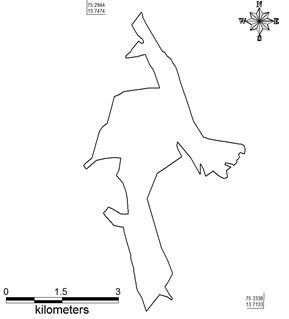

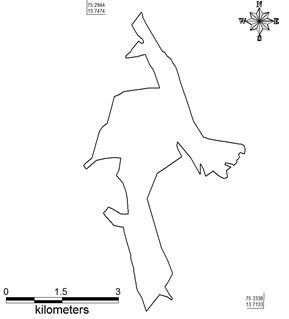

Kullundekan in the taluk of Thirthahalli in Shimoga district was studied in the month of April, 2012, mainly from the vegetational angle and for cognizance of threats facing it. The kan, situated between lat. 13.76° & 13.81° N and 75.43190 Nto 75.42880 E , is spread over in the Survey nos. 25, 27, and 29 covering an area of altogether 453.86 ha. Lack of consolidation of forest areas and conflicting claims of ownerships, allotments for non-forestry purposes by the Revenue Department come in the way of precise boundary identification for Kullundikan. Most other kans of Shimoga district are also plagued with similar problems. Shimoga and Chikmagalur districts were part of erstwhile Mysore State. Kan lands were recognised by the State Forest Department till almost 1970. But after that those survey numbers were merged in Reserved Forests and other kinds of forests including Minor Forests, State Forests and District forests (Gokhale et.al, undated). A Google Earth image of the kan and associated landscape elements is given in the Figure 18. The study localities mainly covered Kullundi, Singanabidare, and Garaga villages. The vegetation ranges from evergreen to semi-evergreen and secondary moist deciduous forests, in addition to their degradation stages ultimately resulting in small bare areas and scrub. The geographical coordinates of 16 study localities, where vegetation was sampled, are given in the Table 10.

Figure 18: Location, topographic, and vegetational features and forest sampling sites.

-

Fragmentation of vegetation: The kan forests were praised in the past for their unique evergreen vegetation of lofty trees, rich, moldy soils, fire security, as source of perennial streams and production of various products in demand for human subsistence, especially as centres of pepper production, a commodity that commanded high prices worldwide. The composition of the landscape elements of the kan does not conform to the past descriptions of such sacred forests from central Western Ghats, being today an assemblage of relics of the evergreens forming an non-cohesive mix with various degraded stages including scrub and periodically fire affected areas. Severe human induced changes in the evergreen forests of Western Ghats are bound to have cascading consequences on human welfare in the Deccan plains mainly because of reduced water flow in the east-flowing rivers. The condition of the forested terrain, the portion mostly falling in the erstwhile spread of the kan area, as depicted in the Forest Map of South India (Pascal et al., 1982) is shown in the Figure 19. (The legend for the map covers more kind of vegetational types than shown in the selected block). Bulk of the forest is evergreen and a portion was once dominated by Dipterocarpus indicus of the climax evergreen type formation of the lower altitudes. However, many mighty trees of the species were cut down for planting coffee and for forest based industries in the past. Many changes appear to have taken place after the preparation of the vegetation map by Pascal, due to land allotments for non-forestry purposes and due to other human interventions.

-

Quantitative studies

Vegetation was studied in 16 sampling localities within the kan using Point-centred quarter method. The geographical coordinates of the localities sampled are shown in the Table 10.

Table 10: Study localities of forest sampling

| Sl |

NAME |

LONGITUDE |

LATITUDE |

| 1 |

Kulundikan-1 |

75.4319 |

13.7911 |

| 2 |

Kulundikan-2 |

75.4312 |

13.7915 |

| 3 |

Kulundikan-3 |

75.4288 |

13.7917 |

| 4 |

Kulundikan-4 |

75.4286 |

13.7913 |

| 5 |

Kulundikan-5 |

75.4285 |

13.7911 |

| 6 |

Kulundikan-6 |

75.4267 |

13.7916 |

| 7 |

Kulundikan-7 |

75.4315 |

13.7951 |

| 8 |

Kulundikan-8 |

75.4307 |

13.7954 |

| 9 |

Kulundikan-9 |

75.4306 |

13.7956 |

| 10 |

Kulundikan-10 |

75.4305 |

13.7958 |

| 11 |

Kulundikan-11 |

75.4349 |

13.7926 |

| 12 |

Kulundikan-12 |

75.4347 |

13.7931 |

| 13 |

Kulundikan-13 |

75.4317 |

13.7940 |

| 14 |

Kulundikan-14 |

75.4315 |

13.7933 |

| 15 |

Kulundikan-15 |

75.4303 |

13.7936 |

| 16 |

Kulundikan-16 |

75.4281 |

13.7956 |

Figure 19: Forest Map of South India (Pascal et al., 1982)

-

Tree species in evergreen-semievergreen forest type

The kan originally had Dipterocarpus indicus and Calophyllum tomentosum dominated climax forests. Clearances have taken place in many places in lands allotted for planting coffee and arecanut, as well as encroachments have happened. The forests would have suffered heavily due to the selection felling of industrial woods during especially 1950’s to early 1980’s, as there were several large canopy gaps. Yet there were many majestic evergreen trees exceeding 30 m in height and of girths exceeding 4-5 m (Figure 20). Of the trees of the emergent type still present in portions of the kan are in addition to D. indicus and C. tomentosum, Ficus nervosa, Ficus callosa, Artocarpus hirsuta, Cyclostemon confertiflorus, Canarium strictum, Bischofia javanica etc, Mangifera indica, Tetrameles nudiflora, Alstonia scholaris etc. The next in order in the height, and belonging to the 20-30 m group were Mimusops elengi, Aphananthe cuspidata, Homalium zeylanicum, Chrysophyllum roxburghii, Strombosia zeylanica, Aglaia roxburgiana, Alseodaphne semecarpifoli etc. Of the still smaller trees of 10-20 m, the notable ones were the palm Caryota urens, Olea dioica, Dimocarpus longan, Pterospermum sp., Sapindus laurifolius etc. Here and there, because of fire and felling deciduous forests of secondary nature have appeared, where the notable species were Lagerstroemia microcarpa, Grewia tilifolia, Spondias acuminate, Terminalia bellirica, T. paniculata, Xylia xylocarpa, Macaranga peltata etc.

Figures 20: Calophyllum tomentosum and Dipterocapus indicus

Some patches allotted for coffee cultivation (Figure 21) has been planted with coffee after fully or partially clearing the trees, whereas one patch of eight acres, allotted to Sri Chidambara Gowda was seen as such without forest clearance or planting of coffee (Figure 22)

Figure 21: Coffee cultivation in a kan area allotted to private farmer

for coffee plantation.jpg)

Figure 22: Area allotted (8 acres) for coffee plantation maintained as forest

The secondary deciduousforests within the kan and their peripheral areas are obviously due to forest fragmentation through cutting and burning. These have come through succession in the place of evergreen high forest of the Western Ghats. Among the notable tree species observed were Grewia Lagerstroemia microcarpa, Terminalia bellirica, T. paniculata, Xylia xylocarpa.

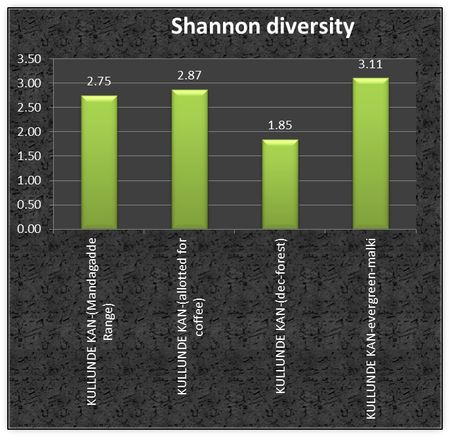

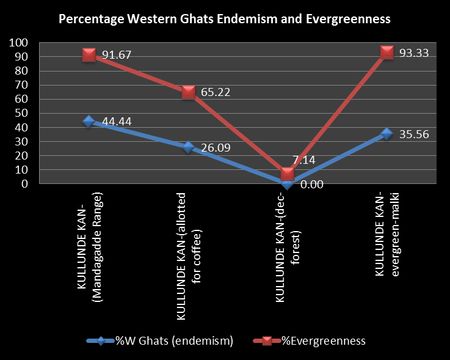

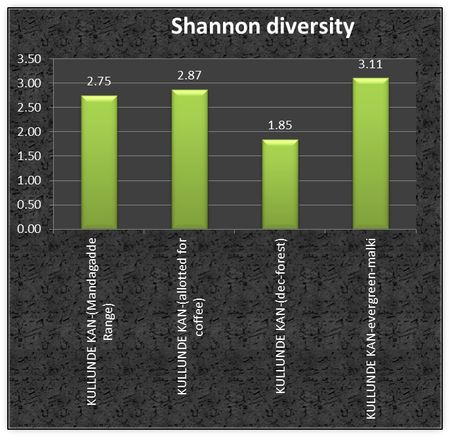

Diversity index (Shannon diversity) for tree species for the evergreen forest was highest at 3.11, for the forest patch allotted to private person and protected as such (figure 23). When a climax evergreen forest of Dipterocarpus indicus and Calophyllum tomentosum domination was partially cleared and planted with coffee, despite the isolated towering trees remaining, the diversity index was lower at 2.75. Yet another portion with coffee had reasonably good number of species, although they were of secondary nature and smaller in stature with diversity index at 2.87. The lowest diversity of 1.85 was for the secondary moist deciduous forest.

Figure 23: Shannon diversity index for tree species in four categories of forests, with the intact preserved forest in malki land showing marginally higher diversity.

-

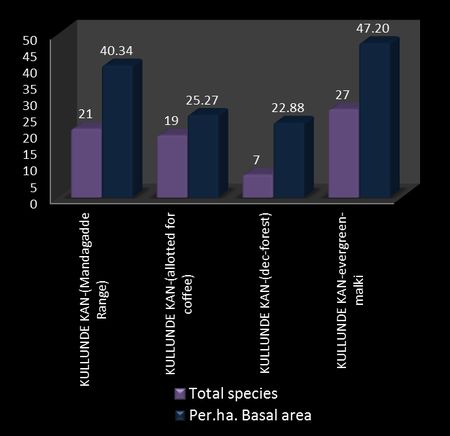

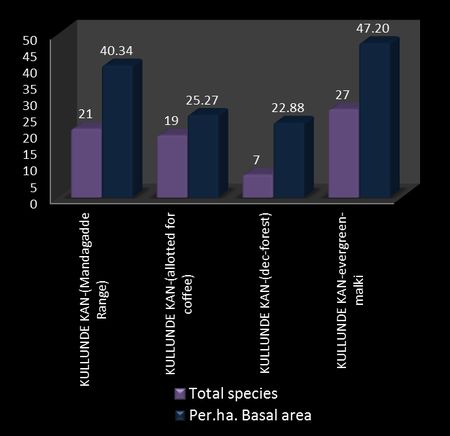

Number of tree species: Part ofKullundekan, partially cleared an panted with coffee, with very large trees still remaining had only 21 species of trees, compared to the intact forest which had 27 species. Another coffee planted area had only 19 species, whereas the deciduous forest had least number as expected (7). Moreover the deciduous patch sampled was too small and degraded and therefore no higher diversity is expected. But opportunistic surveys elsewhere yielded more number of trees in the deciduous forest, the details of which are given in the plant diversity of Kullundikan given as Annexure-3

-

Basal area of trees: Estimated basal areas/ha based on sample surveys of the four patches referred to was highest at 47.2²/ha for the intact forest, followed by 40.34 m²/ha for the coffee area with large proportioned relic trees (Figure 24). Considering the fact that this basal area was for the remnant patch of estimated 69 trees/ha, one could visualize the fact if such a forest were not to be felled for coffee, with 300 plus trees/ha, the basal area/ha could have exceeded 100 m², perhaps the highest for Western Ghat vegetation. Next in importance was the normal coffee planted area without such huge trees and the least was for the deciduous forest.

Figure 24: Tree species numbers and basal area/ha for the forest samples

-