ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT IN ADTR FOCUSSING ON GRASSLANDS

LESSONS FROM HISTORY FOR TIGER CONSERVATION

A Land rich in tigers: The earliest official accounts of Uttara Kannada, and some of the adjoining places in neigbouring districts, covering mostly the 19th century, provides pictures of the richness of tigers and the chilling details of their largescale elimination. According to Colonel Peyton, Conservator of Forests for Kanara during late 19th century, and a great wildlife expert, the tiger’s favourite haunts were near the Sahyadris where they breed in the wildest and most difficult parts. They love to rest in densely wooded river banks and safe cool spots in islands thick with thorns, rank grass, and creepers. According to present day tiger ecologists of tiger is a specilised predator of large ungulates. It is never found far from water. In Asia, the ungulate species diversity and biomass reach maximum where grasslands and forests form a mosaic and where many vegetation types mingle together. In such areas tiger density reaches its maximum. In these relatively closed habitats the tiger lives and hunts these large ungulates alone. On the other hand the lion is group living animal in open habitats and hunt in packs (Campbell, 1883; Seidensticker et al., 1999).

Uttara Kannada of pre-British period was one of pristine sacred groves in almost every village, large stretches of secondary and pre-climax forests, shifting cultivation areas in different stages of vegetational succession, benas or grasslands, maintained by farmers using fire periodically to eliminate woody plants and weeds. The valleys with perennial water sources were associated with rice fields and arecanut cum spice gardens. These were in addition to the natural topographical features of rugged terrain of mounts, and steep hillsides, gorges of rivers, densely wooded ravines and narrow valleys, innumerable streams that merged to form few important rivers, water falls and springs. Such landscape favoured the rich wildlife the district had (Chandran and Gadgil, 1993).

For the early inhabitants of the district hunting was never a sport, but carried out mainly for subsistence and crop protection. The British arrival in the district, first as traders and later as rulers, saw setting in of a new era of wanton hunting of wildlife, more for sport than for subsistence. The chilling statistics of tiger killing in the district as furnished in the Kanara Gazetteer (Campbell, 1883) are given in Tables 8-1 and 8.2.

Table 8.1: Incidents of tiger killing in Uttara Kannada and adjoining districts

| No. of tigers/cubs killed |

Year of kill |

Place of kill |

| 31 tigers |

1840-41 |

Belgaum |

| 1 tiger |

3 April 1875 |

Supa |

| 1 tigress, 1 cub |

5 April 1875 |

Supa |

| 1 tigress & 5 cubs |

1878 |

Tinaighat |

| 1 tiger |

1881 |

Yellapur |

| 1 tiger & 1 tigress |

1882 march |

Yellapur |

| 2 killed, 1 wounded |

? |

Yellapur |

| 1 tigress, 5 cubs |

1882 April |

Potoli, Supa |

Source: Based on Campbell, 1883

Consolidated numbers of tigers killed in Uttara Kannada, during some years of 19th century, as is officially reported in the Kanara Gazetteer (Campbell, 1883) are given in (Table 8-2)

Table 8-2: Statistics of tigers killed in Kanara during 1856-1882

| Year |

Tigers killed (male, female) |

| 1856-1877 |

510 (average 23/year) |

| 1867-1877 |

352 (average 32/year) |

| 1878 |

23 |

| 1879 |

18 |

| 1880 |

39 |

| 1881 |

28 |

| 1882 |

22 |

| Total for 27 years |

992 (37 tigers/year) |

Source: Based on Campbell, 1883

The reasons for tiger decline: From the 19th century records it appears that the reasons for the great fall in the tiger numbers are:

- For protection of humans from tigers: 22 persons were killed between 1856 and 1877. Rewards were paid to the hunters for each tiger and cub killed. Probably, such human kills, could have been due to widespread and intensified hunting of the ungulate animals by British sportsmen and local shikaris.

- For protection of cattle: 4041 cattle were killed during five years, 1878-1882 by tigers and 1617 by panthers. Instead of correlating the high number of cattle kills to the depletion of prey in the wild, it was made a reason for tiger hunting.

- Sports hunting: Hunting developed as a sport during the British period. Graphic descriptions on the growth of hunting ‘technology’ are found in the British records.

- Decline of fire as an ecological factor: The British saw kumri cultivation as a threat to the timber rich forests and failed to note that use of fire for clearing evergreen forests by the kumri cultivators was the reason for enrichment of the rainforests with deciduous timber species, leading with teak, which had great demand nationally and internationally. Fire-swept landscapes where grass grew plentifully in early successional stages of forests could have been significant in wildlife enrichment. The ban on shifting cultivation reduced the role of fire substantially, and itself would have reduced the carrying capacity of the landscape for ungulates, with adverse effects on tiger population.

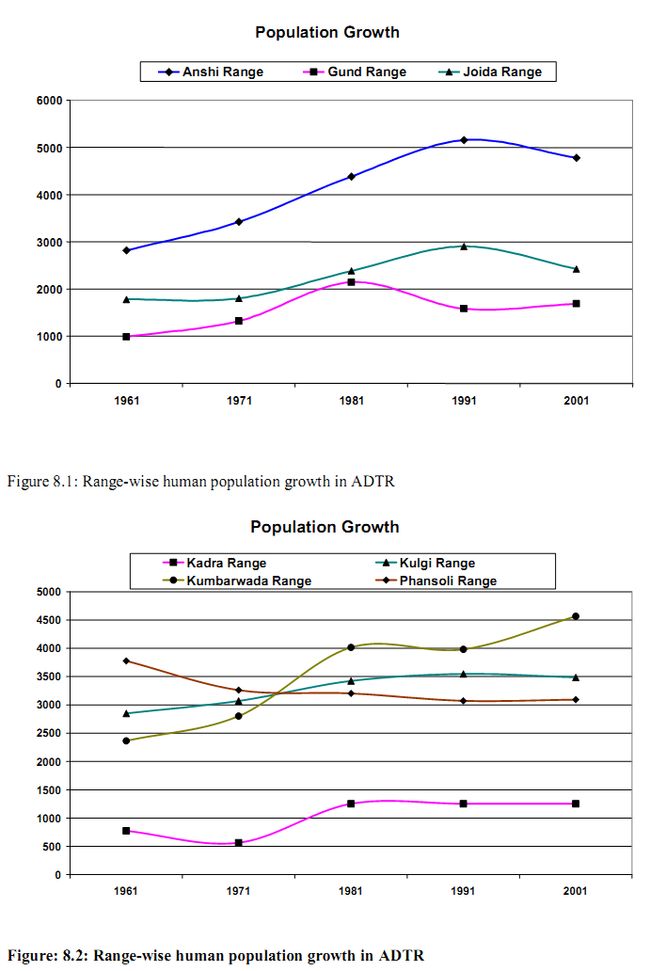

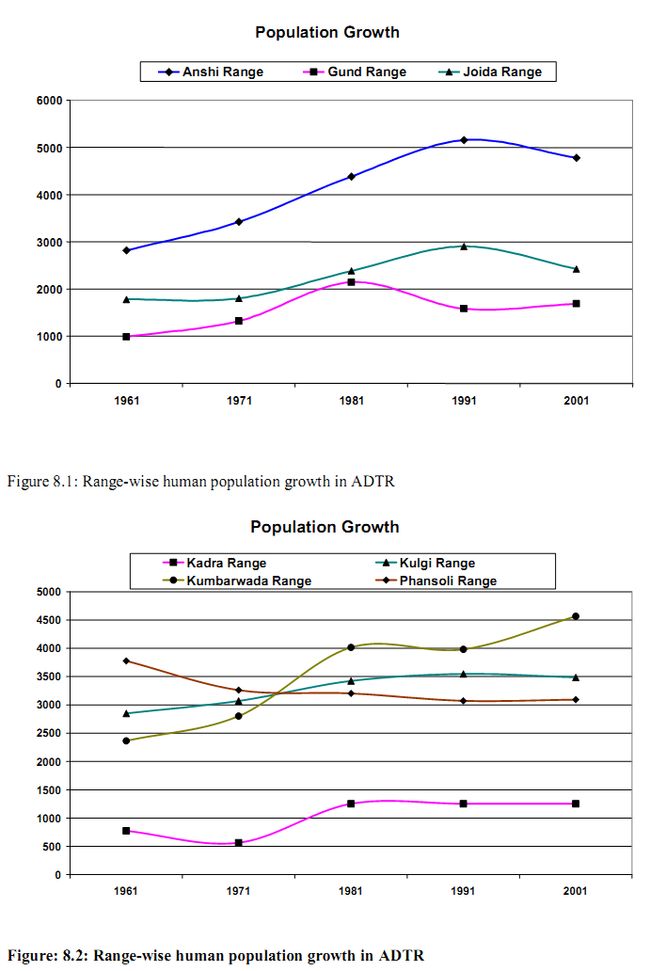

- Increase in human population: The general increase in human population increased pressure on forests and wildlife. Increase in forest based industries, forest logging related human influx, mining in forest areas, construction of a chain of hydel projects in Kali river, submersion of Supa town by the reservoir and resettlement of people in the newly created township of Ramnagar, growth of Dandeli as an important industrial town, the Karnataka Power Corporation settlements in Ambiganagar and Ganeshgudi etc. would have created spillover effects on the ADTR. Linear intrusions in the forests would have increased manifold due to newly developed road networks and power lines. However, in the ADTR Ranges the population growth curve appears to have leveled off or declined during 1991 and 2001 census (from total of 20805 in 1981 to 21496 in 1991 and 21293 in 2001). Except in Kumbarwada Range in the other Ranges the population has stabilized or is showing marginal decline (Table 8-3 and Figures 8.1 and 8.2).

Table: 8-3: Range-wise human population details for 1961-2001

| Range |

1961 |

1971 |

1981 |

1991 |

2001 |

| Anshi Range |

2815 |

3421 |

4385 |

5156 |

4784 |

| Gund Range |

987 |

1321 |

2145 |

1583 |

1686 |

| Joida Range |

1777 |

1803 |

2382 |

2904 |

2425 |

| Kadra Range |

775 |

564 |

1252 |

1252 |

1252 |

| Kulgi Range |

2850 |

3070 |

3423 |

3547 |

3487 |

| Kumbarwada Range |

2365 |

2802 |

4015 |

3982 |

4566 |

| Phansoli Range |

3777 |

3261 |

3203 |

3072 |

3093 |

| Total |

15346 |

16242 |

20805 |

21496 |

21293 |

- Increase in cattle population: The prohibition on shifting cultivation necessitated more permanent cultivation in the valleys. As plant ash could not be added to hill soils, because of decline in the use of fire, the farmers had to keep more number of cattle, mainly for manure. Cattle obviously became competitors for wild ungulates in sharing the fodder resources. At the same time, during the latter half of 19th century, when there was drastic decline of prey animals due to over-hunting, cattle became important prey.

- Impoverishment of grasslands: The stoppage of shifting cultivation gave prominence to settled cultivation and permanent grasslands along hill tops and slopes. Many of the nomadic cultivators, who had not maintained cattle earlier, were compelled to keep them for manure purpose. Constant grazing in the grasslands perpetually maintained by use of periodic fire, to eliminate rank growth, would have caused soil erosion and laterization. Such extensive laterite areas are seen all over the Joida taluk.

- Excess of teak monoculture: Intensive commercial working of forests for hardwood timbers from 19th century unleashed a saga of new wave interference into habitats teeming with wildlife. Timber extraction was followed by often clear-felling of forests to raise teak monoculture plantations. Some of the earliest plantations in the Western Ghats, dating back to 1859, were started in the Kadra Range. With systematic extraction of marketable timbers, according to the forest working plans, from the dawn of the 20th century, teak plantations were raised in portions of the worked forests almost in every coupe. The ecology of natural teak was altogether neglected and nothing was done to maintain a sustainable system of natural forests enriched with teak (Gadgil and Chandran, 1989). In fact the Gund plateau (part of the ADTR) was one of the three well known natural teak forests of the Western Ghats along with the Anamalais and the Wynad-Hegdedevankote forests (Cleghorn, 1861). Raising of teak in large scale impoverished the forest ecosystem as a whole because of: a. forest fragmentation and steep decline of forest biodiversity; b. conversion of healthy grasslands and successional forests into monoculture; c. intense erosion of soil, especially on steep slopes, as protection of the spongy soil mantle from teak canopy during the monsoon months would be insufficient, as compared to the denser canopy of natural forests; d. increased incidence of ground fires due to thick deposit of fallen leaves of teak during the summer months; e. weed invasion (mainly Lantana and Eupatorium) that replaced more benign ground vegetation of native species dominated by Strobialanthus and other native speciesprior to monoculturing; f. Impoverishment of watersheds and drying up of streams in the teak areas.

- Destruction of micro-habitats due to flooding: As Col. Peyton, Conservator of Forests for Kanara noted: the tiger’s favourite haunts were near the Sahyadris where they breed in the wildest and most difficult parts. They love to rest in densely wooded river banks and safe cool spots in islands thick with thorns, rank grass, and creepers (Campbell, 1883). The rise of water level in the Kali and its tributaries due to construction of a series of hydel reservoirs would have submerges lot of tiger microhabitats alongside the rugged banks of the river in the Western Ghats and the small islands strewn with rocks and overgrown with vegetation.

REQUIREMENTS OF THE TIGER

Habitats and home ranges: A single tiger’s home ranges may be anything from 20 to over 400 km², depending on the density and availability of the prey. Therefore protecting large populations will require extensive areas of habitat for conservation. The ecological requirements of tigers and their prey can be effectively used to design landscape-level land use options. Such options include conservation of core areas coupled with restoration of degraded lands, and sustainable natural resource use plans to meet the needs of the local people (Wikramnayake et al., 1998). Tiger can adapt to a variety of habitats. ADTR, receiving a range of rainfall regimes from western portions with extremely heavy seasonal rainfalls (up to 5000 mm) to much lower (barely over 1000 mm) towards the east has habitats ranging from tropical evergreen and semi-evergreen to moist deciduous and dry deciduous forests. Human impacts in these forests through ages have created a variety of derived habitats such as grasslands, savanna and scrub which, enmeshed in a matrix of forests, created the needed heterogeneity for the proliferation of tigers and their prey.

Prey animals and food needs: Mean weight of prey killed by tigers can vary from 15 to 65 kg, down to sometimes 5 kg in some protected areas. The low value perhaps reflects the scarcity of large prey animals (Sunquist et al., 1999). A tigress requires 5-6 kg of meat a day as its maintenance diet (Sunquist, 1981). It was estimated that the tigress’ need of meat would be 1825-2190 kg/year; but as 30% of each carcass is inedible a tigress needs gross quantity of 2373-2847 kg/year of meat. The range of animals killed by tigress may range from 20 kg barking deer every 2-3 days or one 200 kg sambar every few weeks. Based on a study of three National Parks (two in India and one in Nepal) and one Sanctuary in Thailand, it was estimated that the mean mass of prey killed was 14.7 kg in Thailand to 65.5 kg in Nagarahole and 66 kg in Kanha (Sunquist et al., 1999). Details regarding the frequency of mammalian species in the food of tigers in the Nagarahole National Park, based on scat analysis is given in the Table 8-4 (ibid. 1999)

Table 8-4: Details regarding the frequency of mammalian species in the food of tigers in the Nagarahole National Park (based on Sunquist et al., 1999)

| Species name |

Common name |

Mean body mass, kg |

Relative no. killed |

| Axis axis |

Chital, Spotted deer |

55 |

22.8 |

| Cervus unicolor |

Sambar deer |

212 |

11.4 |

| Bos frontalis |

|

287 |

7.5 |

| Sus scrofa |

Pig |

38 |

8.4 |

| Muntiacus muntjac |

Barking deer |

20 |

8.4 |

| Semnopithecus entellus |

Hanuman langur |

9 |

11.3 |

| Moschiola meminna |

Indian chevrotain |

8 |

13.6 |

| Lepus nigricolis |

Black-naped hare |

3 |

1.5 |

| Hystrix indica |

Indian porcupine |

8 |

0.6 |

| Cuon alpinus |

Asiatic wild dog |

15 |

1.0 |

| Unidentified items |

|

|

13.5 |

| Mean mass (kg) of prey killed =65.5 kg |

Nagarahole being more similar to ADTR than any other tiger reserve in India, we expect as well the same prey animals in the latter. We need to see how to increase the numbers of these animals. Most of these depend on grasslands and savannas for their food. Different other habitats also contribute towards the food of these animals; for instance, the langurs are mainly arboreal. Therefore, we need to work out in detail, the ideal combination of landscape elements to maintain and enhance the number of a spectrum of prey animals, from the smallest hare to the largest gaur. Grassland forms the base of the ecological pyramids of all the large prey animals, which are also part of forests and water bodies.

Ideal habitats: Unlike lions or cheetah which need vast grasslands for their prey capture, tigers rely on surprising a prey and capturing it. Hence tigers prefer to inhabit mosaic kind of landscape elements such as dense forest, grasslands, scrub, ravines, wetlands etc. Hence ADTR hosting large number of these landscape elements has good potential to be an ideal place for tiger conservation. In fact the tiger population was very good in the past and the reasons for its decline also have been discussed. According to Karanth (1993), tigers have the ability to live in very diverse natural habitats, where they tolerate a wide range of temperatures and rainfall regimes. They produce relatively large litters with relatively short inter-birth intervals. They can take prey differing considerably in size and their hunting tactics will vary based on prey size, prey species and habitat. Hence due to their diverse selection of prey and larger territorial activities, larger intact diverse habitats are required. However, tiger needs for its prey good population of large sized herbivorous mammals, mostly ungulates. To sustain these herbivores large and healthy grasslands are very essential. Good tiger population in a preserve would reflect good grasslands and large number of ungulate preys. Wildlife managers need to assess habitat requirements of different species, and bring the grasslands under careful management system, particularly with reference to their strategic locations, palatability of grasses and herbs, vegetational succession, willful alterations of them and about their vulnerability to weed menace.

Need for minimizing grazing pressure from domestic cattle: Overgrazed areas near many villages are dominated by weedy species and it is necessary to minimize the number of cattle. This objective could be fully achieved only when such villages are prioritized for rehabilitation of the inhabitants, at least towards reducing the present levels of pressure. Range-wise details of cattle population in the ADTR are furnished in the Table 8-5. Though apparently the cattle number (6170) is not that high for the ADTR, considering that the grasslands here are secondary and created from the forests in the past during the peak period of shifting cultivation, through slashing and burning natural vegetation, grass growth is poor in most of them. Because of the heavy rainfall the region receives, the grasslands, tend to revert to woody vegetation and are also subject to invasion to tall weeds like Chromolaena. Moreover, the substratum of many grasslands is rocky being abandoned kumri areas, and old pastures exposed to alternate intensive rainy season followed by prolonged dry period of six to seven months. These rocky area grasslands produce very less grasses, compared to genuine dry area grasslands of relatively lower rainfall, elsewhere. The protected bena grasslands of individual farmers are better in terms of height and density of grasses, although the grasses there die during the dry season.

Table 8-5: Range-wise details of cattle population in the ADTR

| Sl No. |

Range |

Number of Cattle |

| 1 |

Kulgi |

2202 |

| 2 |

Phansoli |

260 |

| 3 |

Gund |

952 |

| 4 |

Kumbarwada |

1342 |

| 5 |

Anshi |

1414 |

| |

Total |

6170 |

Because of heavy seasonal rainfall exceeding 4000-5000 mm per annum towards the western portions of the ADTR, evergreen-semi-evergreen forests not much favoured by the tigers, constitute the major vegetation types here. There are fairly large agricultural areas within this region and some of them need to be prioritized for rehabilitation of families. These villages can turn into very good secure habitats for tigers, especially during the drier months, due to better availability of water and reduced competition from domestic cattle, which are presently in good numbers. However, more efforts are to be made for maintenance of grasslands in all the heavy rainfall regions. If villages are shifted are entirely there will be no check on the succession of woody forest species and non grass weeds in the grasslands and fallow fields. Through regulated use of fire, involving the local population in such exercises, the succession of forests in abandoned grasslands and fallow fields can be checked.

FOOD NEEDS OF THE TIGER

Promoting plant species for faunal richness: Many kinds of habitats within the ADTR, presently not so favourable for or of below optimum utility for faunal richness can be selectively managed to increase the population of major and minor mammals, birds and bats and various invertebrates like butterflies and bees which add to the attractiveness of ADTR and render various ecosystem services. A list of forest trees, shrubs and climbers which provide food in various forms for the wildlife are given in the Table 8-6. The species can be planted in all the suitable habitats without destroying the existing vegetation. Such habitats to be considered include numerous monoculture plantations within the ADTR, barren rims of reservoirs of hydel projects, roadsides, rocky places with scanty growth of grasses etc.

Table 8-6: Wild woody plants of food value for wildlife

| Sl. |

Species |

Local/common Name |

Parts eaten and wild animals feeding on them |

Remarks |

| 1 |

Acacia concinna |

Seege |

Pods-Deer*, Sambar, Gaur |

|

| 2 |

Acacia ferruginea |

Banni |

Pods-Deer*, Sambar, |

|

| 3 |

Artocarpus integrifolia |

Halasu, Jack |

Fruits-Monkeys, Bear

Leaves- fodder |

Fallen fruits of A.integrifolia and A.hirsutus are relished by many ungulates |

| 4 |

Bauhinia sp. |

Basavanapada |

Pods- Gaur, Sambar, Deer* |

|

| 5 |

Bombax ceiba |

Buraga, Silk cotton |

Flowers-Monkeys, Sambar, Deer*, Wild pig. Nectar for many birds |

|

| 6 |

Careya arborea |

Kumbia, Kaul |

Bark-Sambar, Fruits-Elephant, Monkey, Porcupine, Sambar |

|

| 7 |

Cassia fistula |

Kakke |

Pods-Bear, Monkeys |

|

| 8 |

Cordia macleodii |

Hadang |

Fruits- Deer*, Gaur, birds |

|

| 9 |

Cordia myxa |

Challe |

Friuits-Deer*, Sambar, Bear, birds |

|

| 10 |

Dillenia pentagyna |

Kanagalu |

Fruits-Deer*, Sambar, Gaur, birds |

|

| 11 |

Ficus spp. |

Atti |

Fruit- Birds, including Hornbills, bats etc., and ungulates such as Deer*, Sambar, etc.

Leaves- fodder for herbivores |

Keystone species with one or the other tree flowering throughout the year and eaten by large number of wild animals, both big and small |

| 12 |

Grewia tiliaefolia |

Dhaman; Dadaslu |

Leaves-Sambar, Deer*,Fruits-Monkey, birds |

|

| 13 |

Hydnocarpus laurifolia |

Suranti; Toratte |

Fruit-Porcupine |

|

| 14 |

Spondias acuminate |

Kaadmate |

Fruits: Sambar, Porcupine, Deer* |

|

| 15 |

Kydia calycina |

Bende |

Leaves –Ungulates |

Seems to be eaten by ungulates as they are eaten by cattle. |

| 16 |

Moullava spicata |

Hulibarka |

Fruits-Deer*, Sambar |

Flowering spike is also eaten |

| 17 |

Mucuna pruriens |

Nasagunni kai |

Leaves-Deer* |

|

| 18 |

Phyllanthus emblica |

Nelli; Gooseberry |

Fruits-Sambar, Deer* |

|

| 19 |

Strychnos nux-vomica |

Kasarka |

Fruits- pulp eaten by monkeys, Hornbills |

|

| 20 |

Syzygium cumini |

Nerale |

Fruits- wild Pig, Deer*, Bear and several birds |

|

| 21 |

Tectona grandis |

Saaguvani; Teak |

Bark- Elephants. |

Elephants debark the tree in long strips and consume it. |

| 22 |

Terminalia belerica |

Tare |

Fruits-Deer, Sambar |

|

| 23 |

Tetrameles nudiflora |

Kadu bende |

Bark-Elephants |

Favourite tree for bees to make hives |

| 24 |

Xylia Xylocarpa |

Jamba |

Seeds-Gaint Squirrel, Monkeys |

|

| 25 |

Zizhiphus oenoplia |

|

Fruits-Jackels, Procupine, Deer*, Pangolin, birds |

|

| 26 |

Ziziphus rugosa |

Kaare |

Fruits-Bear, birds |

|

*Deer includes Mouse deer, Barking deer, Spotted deer

Several kinds of grasses are associated with the ADTR; of them many are known as good or very good fodder grasses. The list of fodder grasses in general are given in the Table 8-7. Grasslands with such grasses need to be given special attention in management programmes. List of grasses for planting in Kulgi and Dandeli wild life Sanctuary is given in Tables 8.8 to Table 8.10.

NEED FOR STRICT PROTECTION OF PRIME HABITATS

Tigers are sensitive to high levels of human disturbance. In landscape management programme large core areas are to be earmarked for strict protection. Relocation/rehabilitation of villages, preferably should begin with these identified core areas. The core areas may be identified by abundance of wildlife in general, good water resources and reasonably large sized elements in natural landscapes. Good grasslands need to be linked to large patches of multi-species forests and perennial water bodies.

Control on poaching: Tiger populations were severely depleted in Uttara Kannada due to heavy poaching/hunting during the latter part of 19th century. Panwar et al. (1987) state that tiger populations can recover relatively rapidly, with the sustained availability of food and water alongwith reduced or complete elimination of poaching. Tigers, in favourable situations, are considered to breed faster than their prey. Karanth and Smith (1999) consider prey depletion as a critical determinant of tiger population viability. This fact was not given much attention earlier in conservation circles, which highlighted poaching and habitat loss as the major causes for tiger decline. Their study results suggest that tiger populations can persist in relatively small reserves (300-3000 km²), even if there is low level of poaching, provided prey base is maintained at adequate density. Karanth and Sunquist (1992) and Seidensticker and McDougal (1993) affirm that in high prey-density habitats like the alluvial grasslands and deciduous forests of southern Asia, the necessary protected areas could be as small as 300 km², whereas in prey-poor habitats such as mangrove, evergreen or temperate forests, they may exceed 3000 km².

Suggestions: Core areas and corridors are to be identified on the basis of field studies, animal censuses/observations hitherto carried out and remote sensing data. Corridors to be devised and existing ones have to be strengthened/widened using suitable plant species.

Table 8-7: List of grasses of ADTR , noting those of fodder value

| |

Grasses of Anshi-Dandeli Tiger Reserve |

|

| Sl. No. |

Genus |

Species |

Distribution |

Remarks as fodder |

| 1 |

Aristidia |

Setacea |

India, Sri Lanks, Mascsrene |

Good |

| 2 |

Arthraxon |

Lancifolius |

Paleotropics |

Good |

| 3 |

Arundinella |

Leptochloa |

Peninsular India, Sri Lanka |

|

| 4 |

Arundinella |

nepalense |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

|

| 5 |

Arundinella |

Metzii |

Oriental-Western Ghats |

Good |

| 6 |

Bracharia |

Miliiformis |

Oriental-Indomalaysia, Sri Lanka |

Good |

| 7 |

Centotheca |

Lappacea |

Indo-Malaysia, China, Tropical Africa, Polynesia |

Good |

| 8 |

Chloris |

Barbata |

Tropics |

|

| 9 |

Coelachne |

simpliciuscula |

India, Sri Lanka, China, South East Asia |

|

| 10 |

Coix |

Lacryma-Jobi |

Tropics |

|

| 11 |

Cyanodon |

Dactylon |

India, Sri Lanka, Pantropics |

Good |

| 12 |

Cymbopogon |

Caesius |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka, South West Asia, Africa |

|

| 13 |

Cyrtococcum |

Muricatum |

India, South East Asia |

|

| 14 |

Cyrtococcum |

Oxyphyllum |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

|

| 15 |

Cyrtococum |

Patense |

Oriental-Indomalaysia, Pacific Islands |

|

| 16 |

Dactyloctenium |

Aegyptium |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka |

|

| 17 |

Digitaria |

Bicornis |

Tropical Asia, Africa |

Very Good |

| 18 |

Dimeria |

ornithopoda |

India, Malaysia, Japan, Tropical Australia |

|

| 19 |

Dimeria |

hohenackeri |

Oriental-Peninsular India |

Very Good |

| 20 |

Echinochloa |

Colona |

Most warm countries |

Very Good |

| 21 |

Eleusine |

Indica |

Oriental and Paleotropic |

Good |

| 22 |

Elytrophorus |

Spicatus |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka, old tropics |

|

| 23 |

Eragrostis |

Uniloides |

Asian Tropics |

|

| 24 |

Eulalia |

Trispicata |

Oriental-Indomalaysia, Australia |

|

| 25 |

Heteropogon |

Contortus |

Pantropics |

|

| 26 |

Hygrorhiza |

Aristata |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka |

Good |

| 27 |

Isachne |

Miliacea |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

|

| 28 |

Isacne |

Globosa |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

|

| 29 |

Ischaemum |

thomsonianum |

Oriental-Western Ghats |

|

| 30 |

Ischaemum |

Dalzelli |

|

|

| 31 |

Ischaemum |

Indicum |

South India |

Good |

| 32 |

Ischemum |

semisagittatum |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka |

|

| 33 |

Jansenella |

griffithiana |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka |

|

| 34 |

Leersia |

hexandra |

Tropics |

|

| 35 |

Oplismenus |

Burmanii |

Oriental and Paleotropic |

|

| 36 |

Oplismenus |

Compositus |

Pantropics |

|

| 37 |

Oryza |

rufipogon |

Oriental-India |

|

| 38 |

Panicum |

Auritum |

Oriental-Indomalaysia, China |

|

| 39 |

Echinochloa |

crus-galli |

India, S E Asia and Africa |

Very Good |

| 40 |

Panicum |

Repens |

Pantropics |

Very Good |

| 41 |

Paspalidium |

Flavidum |

S Asia |

Very Good |

| 42 |

Paspalum |

Canarae |

Peninsular India |

|

| 43 |

Paspalum |

Conjugatum |

India, Sri Lanka, old world world tropics |

|

| 44 |

Paspalum |

scrobiculatum |

Oriental-India |

|

| 45 |

Pennisetum |

hoohanackeri |

India, Pakistan, Tropical africa, Madagascar |

|

| 46 |

Pennisetum |

pedicellatum |

India, Tropical Africa |

|

| 47 |

Pseudanthistiria |

umbellata |

Oriental-India |

|

| 48 |

Pseudanthistiria |

Heteroclite |

Oriental-Western Ghats |

Good |

| 49 |

Pseudanthistiria |

Hispida |

Oriental-Western Ghats |

|

| 50 |

Sacciolepis |

Indica |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

Good |

| 51 |

Sacciolepis |

interrupta |

Oriental-Indomalaysia |

|

| 52 |

Setaria |

Pumila |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka, Old world Tropics |

Good |

| 53 |

Spodiopogon |

rhizophorus |

Oriental-Western Ghats |

|

| 54 |

Themeda |

Tremula |

Oriental-India, Sri Lanka |

Good |

RESTORATION OF DEGRADED HABITATS IN BUFFER ZONE

Buffer zone management is very critical in tiger conservation efforts. The buffer zone should not be one with intense human activities and grazing pressures from domestic cattle. The human activities here should be regulated and development guided towards complementing the objectives of ADTR. Activities suggested for the buffer zone are listed below:

- Formation of Village Forest Committees and Biodiversity Management Committees among all the peripheral villages

- Raising firewood and NTFP species to make peripheral villages self sufficient so as to take pressure of the ADTR core and buffer zones

- Starting village fodder farms, under Social Forestry schemes, especially in villages having numerous cattle and insufficient fodder resources

- Training enthusiastic youngsters as tourist guides, volunteers and communicators

- Fencing of small blocks of lands for three to five years from human impact and grazing by domestic cattle, will have very positive impact on forest succession and healthy growth of grasses in overgrazed areas. Once tall saplings are naturally established, the forest will flourish on its own. The protection may be shifted to other unprotected areas after the three to five year period. The forest lands thus protected may be named “Regeneration Blocks”. The vegetational succession in such blocks to be monitored and recorded, preferably by local volunteers. Seeds of suitable tree and shrub species may be disseminated in such areas to promote diversity.

Suggestions: Application of GIS on wildlife distribution within ADTR is critical. Distribution data, to begin with, should cover primary and secondary reports on tigers, panthers and major herbivorous mammals. From existing and freshly collected data bird distribution details can be prepared as well. Birds are also good indicators of habitat quality. From distribution maps thus prepared, areas of importance for tigers and their prey may be demarcated. This would help in understanding ecosystem processes for preparing guidelines of future management of the Reserve. As it is difficult to get exact details of the very few tigers reported from the ADTR, it is very important to track their associate species and use them as proxy for demarcating likely tiger preference habitats within the Reserve.

GRASSLAND MANAGEMENT

It is necessary to maintain different kinds of grasslands within the Reserve as some grazing wild animals prefer short grass areas while others prefer tall grass areas. Mixed savanna-grasslands are favourites of yet others.

Controlled use of fire: ADTR receives high to moderate rainfall and the natural climax vegetation here is forest. Gradual vegetational succession in grasslands towards forest would effectively reduce carrying capacity for grazing animals and thereby affect prey supply for the carnivores. Therefore maintenance and management of grasslands would play a crucial role in sustaining wild fauna. Fire has been an important tool in grassland management in the humid Western Ghat regions. In the grasslands fire burns down the harsh, fibrous old bases and promotes a flush of new growth of fodder grasses. As it is time consuming and expensive to manage the large areas and keep the ecosystems in a dynamic stage to sustain maximum of the tiger population, with the available staff of the Forest Department, trained volunteers, NGOs and wildlife enthusiasts may be used in grassland management with regulated use of fire according to specifically prepared, site-centred management plans. Fire is to be used with caution as repeated fires can dry out a habitat, cause soil erosion and destroy many sensitive species.

Many tree species of food importance for herbivore prey animals of the tiger are associated with burnt savannas. These include Acacia spp., Bombax ceiba, Careya arborea, Cordia spp., Dillenia pentagyna, Kydia calycina, Phyllanthus emblica etc.

Afforestation in grasslands: Grassland within the Reserve, including fallow fields, should not be used for tree planting under normal conditions. The practice of raising block plantations in such grassy blanks is to be altogether dispensed with. Block plantations, and that too of fodder tree species and those trees that provide food for wildlife can be considered in rocky areas with scanty growth of grasses and other herbs. Providing designed corridors (using area specific trees and other life forms) for animal migration through such areas would be a good exercise for keeping the integrity of the ADTR by keeping the ecosystem processes alive. Dinerstein et al. (1999) consider the restoration of habitat integrity in wildlife, a prerequisite for effective dispersal of tigers.

THE PROBLEM OF MONOCULTURE PLANTATIONS

Ever-since commercial forestry began in the ADTR region, over one hundred years ago, during the British period, raising of teak plantations became an accepted practice, almost in every block of forest, after clear-felling the natural tree growth. We do not know exactly how much area has been brought under teak plantations in the ADTR. Teak plantations in general are low diversity areas, with scanty undergrowth of grass. The plantations are drier places than the natural forests, often subjected to soil erosion and ground fires. Despite the fact teak timber fetches fabulous market prices, there has been a moratorium on tree felling within the ADTR. With the objective of increasing the prey population of tigers, the food resources have to be increased. Without in anyway tampering with good teak plantations, the others can be subjected to enrichment planting with various fruit and fodder species, mainly the trees.

Adopting landscape level approach: In small and isolated protected areas the chances for long term survival of megafauna are slim, unless they are linked by natural habitat corridors to permit dispersal of tigers and their prey and are provided with buffer zones to minimize impacts from other land uses. Therefore landscape level approach is essential for tiger conservation (Karanth and Sunquist, 1995).

Suggestions: Evaluation of habitat quality in different parts of the ADTR with their suitability for wildlife in general and tiger in particular needs to be carried out. In such evaluation grassland quality and connectivity with different other landscape elements are important. Management plans have to be prepared to upgrade landscape elements, particularly poor quality grasslands.

GETTING PUBLIC SUPPORT

Tiger in India is a symbol of pride, power and strength. In Indian tradition it is both feared and respected animal and treated at par with the lion. In the local cultures associated with the wooded highlands tiger has been a worshipped animal. This holds good for the hilly terrain of Karnataka as well. In the Uttara Kannada district most villages and even towns have icons of tigers or Hulidevaru inside sacred forests, under sacred trees or in recently constructed small shrines. Tiger is famed as the vahana of the goddess Kali/Durga and Lord Aiyappa. Such incredible sentimental attachment among the public towards this magnificent animal needs to be appropriately utilized for gaining public support for tiger conservation in ADTR. Such support has to come from not only from outside but more so from the people living within the ADTR and its peripheral villages. Volunteers from among the youth, especially from these villages have to be enlisted to work for activities related to tiger conservation, and to develop a positive attitude among the local population. As the too few staff of the Forest Department are insufficient to manage and maintain the ADTR, especially in fire control, regulated use of fire, in grassland maintenance, tree planting, nursery activities, awareness creation, as local guides etc. it will be ideal to have a core group of such volunteers to assist the Department. If trained in bird watching, plant identification, and in disseminating wildlife related information to the visitors, ADTR can gain much from this reposition of confidence in the local population. In the words of wildlife conservationist Peter Jackson (1999): “if tigers are to be conserved, local people’s feelings and needs must be a paramount consideration. Unless they support conservation, the tiger is doomed. They are not necessarily hostile to the tiger; they have greater problems with the deer and wild boar, which ravage their crops. A local tiger can even be seen as a protector against these pests. But people resent being excluded from forests and grasslands, which have been set aside for tigers and other wildlife, and which could provide them with basic necessities….If people’s hostility is to be eliminated so that they can co-exist with tigers and other wild animals, they must be ensured the resources they need from land outside reserves….The tiger is still alive in the consciousness of the Asian peoples, many of whom retain respect for its place in culture and religion. This should be a powerful factor in enlisting public support, and should be used to convince political leaders that it should not be allowed to become extinct in their countries.”

| Table 8.8: List of grasses for planting in Kulgi and Dandeli wild life Santuary |

| {note: to be implemented under technical supervision] |

| S.No |

Genus |

Species |

Best habitat |

Common names |

| 1 |

Arundinella |

metzii |

Open slopes |

|

| 2 |

Arundinella |

leptochloa |

slopes |

|

| 3 |

Brachiaria |

mutica |

moist |

Para grass (cultivated) |

| 4 |

Centotheca |

lappacea |

slight shades |

|

| 5 |

Chloris |

gayana |

|

Rhodes grass (cultivated) |

| 6 |

Chrysopogon |

hackelii |

slopes |

|

| 7 |

Chrysopogon |

fulvus |

slopes |

Ganjigorikahullu, Karada (Kan) |

| 8 |

Coix |

lachrymal-jobi |

Wet, marshy areas |

Job's tear grass |

| 9 |

Cymbopogon |

caesius |

Open dry slopes |

|

| 10 |

Cymbopogon sp |

|

Open dry slopes |

|

| 11 |

Dichanthium |

annulatum |

Open moist |

|

| 12 |

Digitaria |

ciliaris |

moist shady |

|

| 14 |

Eleusine |

coracana |

Open moist places, abandoned fields |

Ragi |

| 15 |

Eulalia |

trispicata |

slopes |

|

| 16 |

Heteropogon |

contortus |

Open slopes |

Spear grass |

| 17 |

Panicum |

maximum |

moist |

Guinea grass (cultivated) |

| 18 |

Panicum |

auritum |

river side, moist slopes |

|

| 19 |

Pennisetum |

purpureum |

Banks of rivers, moist places |

Napier grass (cultivated) |

| 20 |

Saccharum |

spontaneum |

Banks and wet places |

Kan-kabbu |

| 21 |

Sporobolus |

indicus |

Dry |

|

| 22 |

Themeda |

tremula |

Open slopes |

|

| 23 |

Themeda |

triandra |

Open slopes |

|

Notes on some important grasses

- Brachiaria mutica (Para grass) is a very tall (up to 2.5 m) grass native to South America and West Africa. The grass is a good fodder grass suitable for moist, swampy, open areas. Grass planting is to be done during the onset of monsoon or in cool months. The plants are raised from rooted, mature stem cuttings of 20-30 cm long having 2-3 nodes or from rooted runners. The cuttings root in about six days and begin to spread out. If this grass is to be maintained the soil has to be moist during dry months. The unirrigated grass though dries up sprouts with the beginning of rains. The grass is highly succulent, palatable and nutritious.

- Centotheca lappacea prolifically branched, perennial grass that attains up to 1.5 m height. It is found in open, dry stony regions, especially on laterite soils. If the soil is stony the grass remains stunted. The grass is a good fodder and can be stored as hay. The fodder value is high before flowering.

- Chloris gayana (Rhodes grass) is a fine stemmed, annual or perennial grass introduced as a fodder grass into India from South Africa. It is ideally suited for dryer part of the ADTR, where the rainfall does not exceed 125 cm. It is drought tolerant and good for light loamy soils than stiff clay or water logged areas. Seeds or rooted cuttings are used for propagation. It attains height of 1-1.5 m. Sowing of seeds to be done with the onset of monsoon. While sowing fine soil has to be mixed with seeds so as to have uniform spread. Rooted cuttings can also be planted in rows 60 cm apart. Below power lines with light soils would be ideal. The grass is nutritious and withstands grazing and trampling.

- Chrysopogon fulvus: Perennial tufted grass up to 1.8 m.

- Eleucine coracana: Ragi seeds can be dispersed in all suitable areas to promote growth of wildlings in due course of time. The plants, though seasonal, make good forage. Ragi was grown widely once by the shifting cultivators of ADTR in patches of forests cleared and burnt. Ragi plant is a nutritious fodder.

| Table-8.9 : List of Leguminous plants for planting in Kulgi and Dandeli wild life Santuary |

| Sl.No. |

Genus |

Species |

|

| 1 |

Bauhinia |

purpurea |

Basavanapada |

| 2 |

Bauhinia |

Racemosa |

Banne |

| 3 |

Bauhinia |

variegata |

Arisinatige |

| 4 |

Cassia |

fistula |

Kakke |

| 5 |

Crotolaria |

juncea |

Sunhemp |

| 6 |

Desmodium |

triflorum |

|

| 7 |

Entada |

scandens |

Hallekayiballi |

| 8 |

Erythrina |

spp. |

Harivana |

| 9 |

Indigofera |

cassioides |

|

| 10 |

Pithecellobium |

dulce |

|

| 11 |

Saraca |

asoca |

|

| 12 |

Sesbania |

grandiflora |

Agase |

| 13 |

Smithia |

conferta |

|

| 14 |

Smithia |

sensitiva |

|

| 15 |

Tephrosia |

purpurea |

|

| 16 |

Tamarindus |

Indicus |

Tamarind |

Some notable legumes

- Cassia fistula leaves have fodder value though the cattle are not fond of it. It is likely that some wild ungulates would feed on the leaves. Bears and monkey feed on the fruit pulp according to Talbot (1909), and therefore the tree renders good ecosystem services. Moreover the beautiful, golden yellow bunches of flowers are great attraction during the summer months. The tree can be extensively raised on roadsides and other open, even lateritic areas with poor grass growth. The seedlings are routinely raised in forest nurseries using well-established silvicultural practices.

- Desmodium triflorum: A small, trailing, perennial herb it is a good fodder. It spreads on the ground and forms a close mat; good for nitrogen enrichment and soil conservation.

- Entada scandens: A giant woody climber associated with deciduous and semi-evergreen forests. The leaves are fodder for elephants. Plants can be multiplied by layering or from seeds.

- Erythrina spp. Leaves make good fodder. The tree is good for deciduous forests, roadsides and open places. Stem cuttings are ideal for propagation. The flowers are visited by many birds for nectar.

PULSES FOR INTRODUCTION

Pulses are leguminous herbs and climbers the seeds of a great variety of which have been used as protein rich food by humans from ancient times. Not only are the seeds rich in proteins but the forage also is rich in proteins, mainly because of the association of the roots of these plants with nitrogen fixing bacteria. The very growth of the legumes enriches soils with nitrogen and they are ideal for reclaiming impoverished soils. Dispersing the seeds of relatively low cost pulses selectively, especially along roadsides, as well as raising them in small protected patches, and in canopy gaps of plantations, underneath power lines etc., in due course can increase the stock of these useful plants, as wildlings in the ADTR. The plants will provide excellent forage for many herbivores which constitute the prey stock of tigers. A list of these forage legumes are given below:

- Dolichos biflorus (Eng: Horse-gram; Kan: Kulthi): It grows on a variety of soils, including poor soils, and is hardy and drought resistant. It is considered a valuable green fodder crop and a good protienaceous substitute for grasses. The plants improve soil fertility, which is very necessary for many parts of ADTR where shifting cultivation was widely practiced leaving behind thin layer of poor soils impoverished of nutrients. Underneath poor grade plantations also the species can be raised.

- Dolichos lablab var. typicus (Kan: Avare). It is a good climber, cultivated for the tender pods and seeds used as human food. The plants, both fresh and dry, make good protein rich fodder for herbivores.

- The seeds of various pulses such as of blackgram, green gram, cowpea (alsande) etc may be dispersed in suitable localities so as to increase their number through natural propagation as wildlings.

| Table -8.10 : Nonl-leguminous fodder trees and climbers |

| 1 |

Artocarpus |

integrifloia |

Jackfruit |

| 2 |

Caryota |

Urens |

Palm |

| 3 |

Dillennia |

pentagyna |

Kanigala (Kan) |

| 4 |

Emblica |

officinalis |

Nelli (Kan); gooseberry (Eng) |

| 5 |

Ficus |

religiosa |

Pipal |

| 6 |

Ficus |

bengalensis |

Banyan |

| 7 |

Mallotus |

phillippensis |

Kumkumadamara (Kan) |

| 8 |

Mangifera |

Indica |

Mango |

| 9 |

Mimusops |

elengi |

Bakula (Kan) |

| 10 |

Sygygium |

Cumini |

Jamun |

| 11 |

Zizhiphus |

Rhugosa |

Mulla hannu |

Note: Artocarpus integrifolia: The jack fruit tree can be raised in forest openings, roadsides, field bunds etc. The evergreen tee requires protection for some years from browsing by animals. There is good scope for raising thousands of trees in the ADTR. The leaves are eaten by elephants and most ungulates. The large fruits also make ideal food for many herbivores during summer months and early part of rainy season.

Bauhinia purpurea: A medium sized, tree suitable for savanna with hardened surface and roadsides especially in the ADTR. Apart from having ornamental value due to its deep pink to white, fragrant flowers the leaves have fodder value as well. The leaves contain 3.6% protein and 9.7% carbohydrates and are rich in minerals, especially calcium and phosphorus. It is raised from seeds and the seedlings are transplanted. It can be raised at site by line sowing. Light demand being moderate, should not be planted in fully open places (Talbot II, 1976; Wealth of India, vol. 2, 1988).

Bauhinia racemosa is a small, crooked bushy leguminous tree of moist and dry deciduous forests; useful for filling blanks in forest plantations. Propagation is done by line sowings. The young plants are kept weeded and the soil is loosened from time to time. The tree is a light demander. It produces root suckers and coppices well.

Bauhinia variegata: The tree is not natural to the ADTR. However, being indigenous tree present throughout India it is ideal for introduction, particularly along the roadsides. While the leaves are good fodder the showy flowers provide ornamental value. The leaves have by dry weight 3.58% digestible protein and 14.3% digestible starch and are rich in minerals. The flowers and flower buds have food value even for humans. Known as Kovidara in Sanskrit the plant is also reputed medicinally (Wealth of India, Vol. 2, 1988).

Caryota urens: Elephants are fond of the leaves and starchy pith of the palm that is often associated with evergreen-semi-evergreen forests. Fire protected moist deciduous forests can be planted with this species, especially in gullies and ravines and along the water courses. The palm is propagated through seeds. Self-sown seeds germinate in 150-180 days. Pre-soaking of seeds in cold water for 24 hours ensures the maximum germination in a minimum period. The palm lives for 20-25 years (Wealth of India, vol.3- 1992).

Dillenia pentagyna: Deciduous tree of deciduous forests and burnt savanna. Deer is fond of fruits; many birds also feed on fruits. The tree reproduces by seeds, and is ideal for planting in places subjected to fire. The species also produces coppice shoots.

Dioscorea spp.; Tuber producing climbers. The tuber is eaten by deer. The plans can be raised from tubers.

Emblica officinalis: Fruits eaten by a variety of wildlife. Leaves make fodder for wildlife. There is good scope for raising thousands of trees in ADTR using nursery raised saplings.

Ficus religiosa: The tree can be introduced in unproductive, open, non-grassy areas (as good grasslands should not be brought under any tree plantations). Elephants are fond of pipal leaves. Ficus sp. are considered keystone resources of ecosystems by providing food, in the form of ripe fruits, to birds and many herbivores, during times of scarcity of other seasonal fruits.

Ficus bengalensis: Same habitats as the previous one. Prolific producer of fruits for birds, monkeys and minor mammals. Elephants and ungulates feed on the leaves

Ficus racemosa: The wild fig grows in ravines, gullies, banks of water courses and different other habitats. Being a prolific producer of fruits a-seasonally, there is good scope for raising thousands of trees of this species in ADTR, which can benefit a variety of herbivores, including birds.

Mallotus phillippensis: A small tree that prefers partial shade. The leaves have fodder value. Seldom any importance has been given to this tree, that is also medicinally important, in forest planting. The tree can be propagated by seeds.

Mangifera indica: The mango trees, especially of the wild or semi-wild Appe-midi varieties can be propagated in the forest. The fruits are eaten by several herbivores, and the leaves, though not a good fodder, are sparingly eaten by many animals. The tree will have a great role in ecosystem enrichment.

Madhuca indica and M. longifolia : These are large trees associated with deciduous forests. Leaves make excellent fodder. The fruits are eaten by monkeys, large birds such as hornbills and also bats. The trees are raised from seeds. Even fallen flowers are eaten by herbivores. There is tremendous scope for increasing the population of this useful tree which is a light demander.

Mimusops elengi: Large evergreen tree suitable for planting in evergreen-semievergreen forest areas, in haps and openings. Leaves make medium quality fodder. Fruits constitute food for many birds, bats and other wildlife. The tee is propagated by nursery grown seedlings.

Odina wodier: Moderate to large sized deciduous tree. Leaves are readily browsed by ungulates and fruits eaten by birds. The light demanding and fire tolerant tree produces root suckers as well as coppices well. The tree can be grown from cuttings as well as seeds.

Spondias mangifera: Ctuttings and seeds, light demander.

Bamboos: Different species of bamboos need to be propagated in poor grade plantations. Young shoots and tender leaves of bamboos constitute good fodder for elephants and ungulates.