|

|

GRASSLANDS OF THE WORLD

Grasslands are of many types, and are associated with all the continents of the world, barring the Antarctica. Latitude, soil and local climates for the most part determine what kinds of plants grow in particular grassland. Natural grassland is a formation in low rainfall areas where the average annual precipitation is normally just enough to support grasses, and in some areas a few trees. The precipitation is so erratic that drought and fire prevent large forests from growing. Grasses can survive fires because they grow from the bottom instead of the top. Their stems can grow again after being burnt off. The soils of most natural grasslands are also too thin and dry for trees to survive.

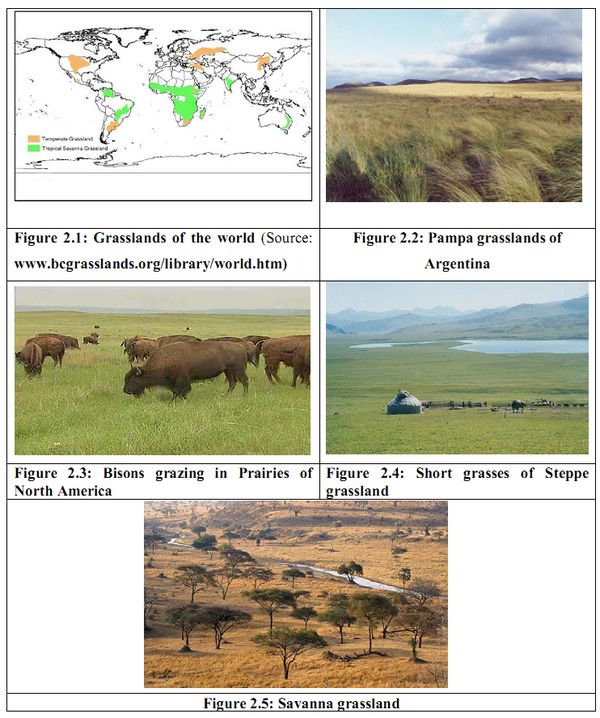

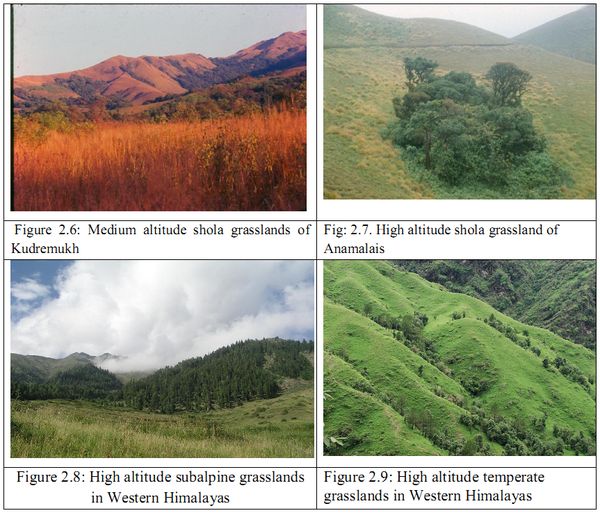

The Grasslands in the southern hemisphere receive more precipitation and support taller grasses than those in the northern hemisphere. In Argentina of South America, with a humid climate, the grasslands are known as Pampas. A large area of grassland that stretches from the Ukraine of Russia all the way to Siberia is known as the Russian and Asian Steppes. The climate in this region is very cold and dry because there is no nearby ocean to get moisture from; winds from the Arctic aren't blocked by any mountains either (www.blueplanetbiomes.org/grasslands). In the Miocene and Pliocene Epochs, which spanned a period of about 25 million years, mountains rose in western North America creating a continental climate favoring the spread of grasslands and decline of ancient forests in the interior plains. Following the Pleistocene Ice Ages, grasslands expanded in range as hotter and drier climates prevailed worldwide. But natural grasslands today have highly decreased; for instance the tall grass prairie of Ontario is only three percent of the original extent (www.ucmp.berkely.edu/exhibits/biomes/grasslands). Grasslands can be broadly divided into Temperate grasslands and Tropical grasslands or savannas (Figure 2.1).

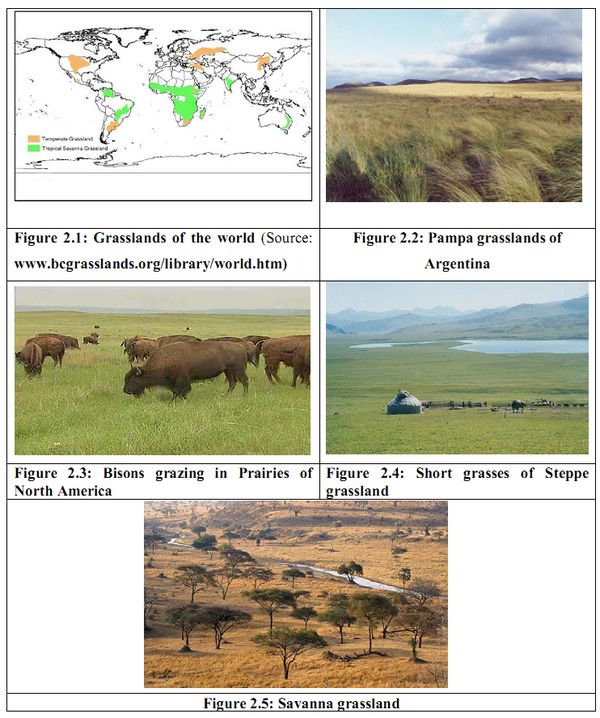

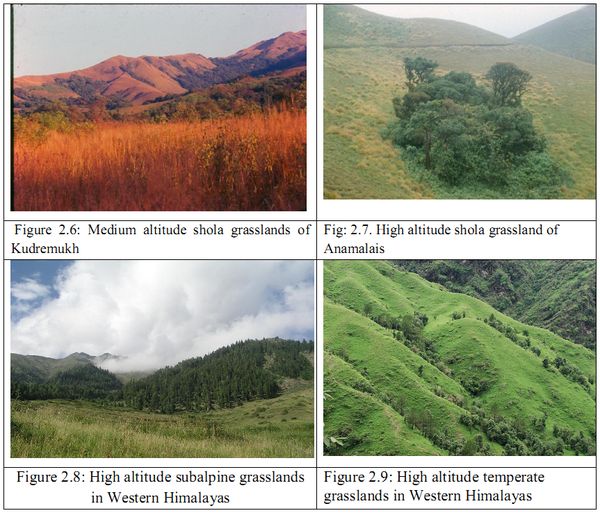

Temperate grasslands: Temperate grasslands are characterized by the general absence of trees and large shrubs. The ‘Veldts’ of South Africa, the ‘Puszta’ of Hungary, the ‘Pampas’ (Figure 2.2) of Argentina and Uruguay, the and the ‘Prairies’ (Figure 2.3) of Central North America ‘Steppes’ (Figure 2.4) of the former Soviet Union, belong to this category. Summers here are hot, winters cold and rainfall moderate, lower indeed than in tropical savanna grasslands. Summers here are hot, winters cold and rainfall moderate, lower indeed than in tropical savanna grasslands (http://www.hamiltonnature.org/habitats/grasslands). The grasses attain greater heights in wetter than in drier regions. Seasonal drought and occasional fires have decisive influence on biodiversity.

Tropical Grasslands (Savannas): The word ‘Savanna’ is derived from the Caribbean Indian language in which Sabana means forest clearings. (Savannas are grass dominated lands with scattered individual trees). Savannas of one sort or other cover almost half the surface of Africa (about eight million square kilometers, generally in Central Africa), large areas of Australia, South America, and India. Climate is the most important factor in creating a savanna, always found in warm or hot climates where the annual rainfall ranges from 51-127 cm (www.ucmp.berkely.edu/exhibits/biomes/grasslands). The rainfall here is confined to four to eight months a year, followed by a spell of drought punctuated with fires. If the rains were to be well distributed throughout the year, many such savannas would turn into tropical forest.

Savannas can be in general divided into:

- Climatic savannas: These savannas are derived from climatic conditions. Their change into other forms depends on climatic variations.

- Edaphic savannas: Savannas resulting mainly from soil conditions such as hill soil, clayey water logged soil etc.

- Derived savannas: Most of the Indian grasslands of plains and low altitude hills belong to this category. They are considered to be derived from slashing and burning of forests and other human impacts. Variations in rainfall and soil conditions between different savannas maintain different grass species of which some become dominant.

Indian Grasslands: The climax vegetation of India is either forests or desert vegetation (Misra, 1980). These grasslands exist solely due to the anthropogenic activities such as lopping, burning, shifting cultivation and grazing for the last several thousand years. The tropical grasslands of India are often referred as savanna. Maximum growth rates are found at about 35°C, about 10°C warmer than the optimum for temperate grasses, and at light intensity twice the optimum. The reason for this is that most tropical grasses have a different photosynthetic mechanism compared to temperate grasses. These biochemical reactions have given rise to C4 and C3 plants (Misra, 1980). During the last few thousand years, the Indian grasslands have undergone many changes. The West Indian desert (Thar) of Rajasthan today is characterized by a hot and dry summer followed by a cold winter. Historical evidence indicates that the area was under forests some 2000 years ago but was gradually destroyed by man for agricultural practices and became desert due to excessive dryness. In the North-Eastern region, under a hot and humid climate, where rainfall exceeds 1,000 cm (world’s highest), there has been development of dense evergreen forests of rich biodiversity. Over a long period of time, tribes and local peoples in this region have cleared forests and practiced Jhum (shifting) cultivation leading to the conversion of primary forests to secondary forests to grasslands (www.pages-igbp.org.; Ramakrishnan, 1992). Indian savannas during the past four centuries are stated to have changed from moderately moist (mesic) to arid (xeric) conditions favoring common woody elements like Acacia nilotica, A. senegal, A. catechu, Calotropis gigantea, Mimosa sp., Phoenix sylvestris and Ziziphus nummularia. Indian grasslands are tentatively divided into eight major types (Whyte R.O., 1954, 1957):

Many of the hilly forested areas of Western Ghats were under shifting cultivation by forest dwelling people, such as the Kunbis, Kumri Marattis etc. of Uttara Kannada. Patches of forests were cleared by cutting and burning, and cultivated the cleared lands for two or three years. As prolonged cultivation would cause soil erosion, decrease soil fertility and increase pest pressures the shifting cultivators would repeat this process in another patch of forest. After many years when forest had regrown on abandoned lands the cycle would be repeated (Chandran, 1998). In India, this system of cultivation is widespread to this day in the Northeastern states. It was banned in most of the South Indian Western Ghats by the British, during late 19th Century. Considerable part of the Anshi Dandeli Tiger Reserve (ADTR) was affected by this system. Whereas forests have re-grown in old shifting cultivation areas, there are very good stretches of savanna grasslands still within the Reserve. These are good examples of derived savannas. The periodic firing of these savanna grasslands keep them in their present state. If fire factor is stopped these savannas have chance to revert to forest if the ground is not rocky or severely eroded. Grasslands associated with wind exposed medium altitude of 1000-1600 m (eg. Kudremukh, Bababudan) and higher altitudes of >1600 m (eg: Anamalais and Nilgiris) are known as ‘shola’ grasslands. These grasslands alternate with stunted evergreen forests in the wind sheltered folds of hills (Figures 2.6 & 2.7) The species found here are Andropogon pertusus, Ischaemum pilosum, Themeda imberbis, Cymbopogon polynuros, Eragrostis nigra etc. Extensive areas of temperate, subalpine and alpine grasslands occur in the higher altitudes of the Himalayas (Figures 2.8 and 2.9)

Indian grasslands are broadly grouped into eight major types (Whyte, 1954, 1957) as in Table 2.1:

Table 2.1 Major types of Indian grasslands and their distribution

| Sl |

Type |

Dominant grasses |

Associated grass sp. |

States occurring |

| 1 |

Sehima-Dichanthium |

Sehima sulcatum, S. nervosum, Dichanthium annulatum, Chrysopogon montanus and Themeda quadrivalvis. |

Ischaemum rugosum, Eulalia trispicata, Isilema laxum and Heteropogon contortus. Themeda and Heteropogon are more extensive on hilly tracks. |

Black soils of Maharastra, Madhya Pradesh, south-western Uttar Pradesh and parts of Tamilnadu and Karnataka. |

| 2 |

Dichanthium-Cenchrus |

Dichanthium annulatum and Cenchrus ciliaris are very important fodder grasses |

Perennials like Bothriochloa pertusa, Heteropogon contortus, Cynodon dactylon and the annuals, Eragrostis tennela, E. tremula, E.viscosa, E.ciliaris, Aristidia adscensionis and Dactyloctenium aegyptium. Well drained wet soils are characterized by Desmostachya bipinnata and Dichanthium annulatum. |

Sandy loam soils of the plains of Punjab, Haryana, Delhi, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, eastern Madhya Pradesh., coastal Maharastra and Tamilnadu. In dry areas of Rajasthan, Saurastra and Western Madhya Pradesh, after severe grazing these are replaced by sparse population of annuals. |

| 3 |

Phragmitis-Saccharum |

Phragmitis karka, Saccharum spontaneum, Imperata cylindrica and Bothriochloa |

|

- Terai areas of northern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Bengal, and Assam. Swamps of Sundarbans and Cauvery delta of Tamilnadu.

|

| 4 |

Bothriochloa |

Bothriochloa odorata |

|

high rainfall paddy areas of Lonavala track of Maharastra is only with dense growth of Bothriochloa odorata |

| 5 |

Cymbopogon |

Cymbopogon spp. |

Themeda, Heteropogon and Aristida. |

Low hills of the Western Ghats, Vindhyas, Satpuras, Aravali and Chota Nagpur |

| 6 |

Arundinella |

Arundinella nepalensis, A.setosa with Themeda anathera form extensive stands with sporadic growth of Chrysopogon spp. |

|

High hills of the Western Ghats, Nilgiris, and throughout on lower Himalayas from east in Assam to west in Kashmir. On the Himalayas, between 1500 m to 2000 m |

| 7 |

Deyeuxia-Arundinella |

Deyeuxia, Arundinella, Brachypodium, Bromus and Festuca sp. |

|

Temperate regions of the upper Himalayas between 2000 m. to 3000 m. from Assam, Bengal through Uttar Pradesh to Punjab and Himachal Pradesh |

| 8 |

Deschampsia-Deyeuxia |

Deyeuxia, Deschampsia, Poa, Stipa, Glyceria and Festuca. Deschampsia and Trisetum spicatum extend even beyond 5000 m. |

|

Restricted to the Himalayas above 2500 m in the alpine to subartic region. |

|