Efforts made to mitigate and manage the floods

Sustainable urban development is possible only with the effective good governance at local levels. These are more effective than statutory authorities in mobilising community resources and undertaking local action to improve or protect the local environment. There is a need to integrate the functioning of all parastatal agencies. Transferring lakes to local government ownership provide an incentive for collective community action against polluters. In 1988 the Government transferred responsibility for 114 tanks within the conurbation area from the Minor Irrigation Department to the Karnataka Forest Department (KFD). The total area of the tanks is 1584 ha, of which 220 ha are under unauthorised occupation. Between 1988 and 2000, the KFD fenced 37 tanks and posted watchmen, and undertook minor improvement works at 10 tanks. In Calcutta, for example, the major drainage is the responsibility of the Irrigation Department and the minor drainage is the responsibility of local governments. In Bangalore, local governments have to coordinate with the KFD, the Minor Irrigation Department, and the BDA.

Three statutes define the responsibilities and powers of local governments in Karnataka:

- The Karnataka Municipalities Act 1964, which applies to the CMCs and the TMC;

- The Karnataka Municipal Corporations Act 1976, which applies to the BMP;

- The Karnataka Panchayat Raj Act 1993,which applies to the panchayats.

Each statute sets out obligatory and discretionary functions and specific powers. The functions are in partial alignment with the functions that the Twelfth Schedule to

The Consitution) Seventy-fourth Amendment Act 1992.

The 73rd and the 74th amendments to the Indian Constitution in 1994 have been regarded as landmarks in the evolution of local governments in India. The Constitution (73rd Amendment) Act, 1992 (commonly referred to as Panchayat Raj Act) came into effect on April 24th, 1993 and the Constitution (74th Amendment) Act, 1992 (the Nagarpalika Act) came into effect on June 1st, 1993. While the 73rd amendment provides for constitution of Panchayats in rural areas, the 74th amendment provides for constitution of Municipalities in urban areas. Since local government is a State subject in Schedule VII to the Constitution, legislation with respect to local government can only be done at the State level. Therefore, upon the coming into force of the 73rd and the 74th amendments, it was the task of the respective States to pass laws in conformity with the amendments.

The Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP):

In 1984, the Government of Karnataka approved the first CDP for BMA. The Government approved a revised plan in 1995 (GO Bi. HUD 139 MNJ, 5 Jan 1995). The CDP covers the entire 1279 km2 of the BMA, comprising a 565 km2 “Conurbation Area” and a 714 km2 Green Belt. The CDP permits only a few types of development in the zone. BDA can demolish any construction in the Green Belt without its approval. However, extensive construction has taken place within the Green Belt. .

Under

The Karnataka Town and Country Planning Act 1961, any new layout in the region requires the approval of the BDA. The widespread practice of forming sites for sale out of agricultural land contravenes the

Karnataka Land Reforms Act, the

Karnataka Land Revenue Act, and the

Bangalore Development Authority Act. Verification of development in the region, reveals numerous discrepancies from the CDP (

Table 9.1 and

Table 9.2).

Table 9.1 Deviations from CDP

| Name of the village |

Survey nos. |

Proposed CDP Land use |

Existing development |

| Bommanahalli CMC |

| Puttenahalli |

31 - 41, 55 - 60 |

Park |

Residential |

| |

29,30 (part) |

Residential |

Forest nursery |

| |

51,61 (part) |

Public & Semi Public |

Mango garden |

| Sarakki kere |

24,25 |

Park |

Residential |

| Billekally (DoresanypaIya) |

151 (part), 154 |

Residential |

Industry |

| Jaraganahalli |

24,25 (Part) |

Traffic & Transportation |

Residential |

| Arekere |

26, 30 |

Industry |

Residential |

| Hongasandra |

33, (part) |

Residential |

Industry |

| Bommanahalli |

61 |

Park |

Residential, industrial |

| Kodichikkanahalli |

3, 4, 5, 6 (parts) |

Commercial |

Residential |

| |

34, 35 (part) |

Public & Semi Public |

Residential |

| Devarachikkanahalli |

20, 21 (part), 19 (part) |

Public & Semi Public |

Residential |

| Hulimavu |

77 (part) |

Park |

Industry |

| |

86 |

Park |

Residential |

| |

76, 78 (part), 79 (part) 80 |

Industrial |

Predominantly residential |

| Krishnarajapura CMC. |

| Kowdenahalli |

82-84, 86, 87, 88 (part) |

Industrial |

Residential |

| |

89 |

Public & Semi Public |

Residential |

| |

90, 91, 92 |

Traffic & Transportation |

Residential |

| Virjnapura |

121 (part), 118-119 (part) |

Park |

Residential |

| |

23 (part), 24 part), 103 (part) 104 (part) |

Traffic & Transportation |

Residential |

| |

34 (part), 35 (part), 42 (part) |

Park |

Residential |

| Krishnarajapuram |

115 (part), 123 (part), 112 (part) |

Public & Semi Public |

Residential |

| G M Palya |

123, 124 |

Industry |

Residential |

| Devasandra |

4 (part), 5, 6 (part), 7 (part) |

Residential |

Industry |

| Vibhuthipura |

104 (part), 105 (part), 106 (part), 170 (part), 205 (part) |

Railway |

Residential |

| |

108 (part), 110 (part), 184 (part) |

Park |

Residential |

| Bhattarahalli |

50, 51, 53, 54 (all part) |

Green Belt |

Industrial and residential |

| Medahalli |

All survey nos. |

Green Belt |

Industry |

Table 9.2: Land use Pattern in BDA Area

| Category |

Area (Hectares) |

Area (%) |

| Residential |

16,042 |

14.95 |

| Commercial |

1,708 |

1.59 |

| Industrial |

5,746 |

5.36 |

| Park and open spaces |

1,635 |

1.52 |

| Public, semi-public |

4,641 |

4.33 |

| Transportation |

9,014 |

8.40 |

| Public utility |

192 |

0.18 |

| Water sheet |

4,066 |

3.79 |

| Agricultural |

64,243 |

59.88 |

Souce: CDP, 2006

City Development Plan (CDP, 2006. City Development Plan for Bangalore, BMP, Bangalore), prepared for the city of Bangalore by BMP, is a 6- year policy and investment plan (2007-12) designed to articulate a vision of how Bangalore will grow in ways that sustain its citizens’ values. Bangalore city has developed spatially in a concentric manner. However, the economic development has occurred in a different manner in different sectors of the City. The current urban structure results from the interlocking of these two developments. Five major zones can be distinguished in the existing land occupation:

- 1st Zone - The core area consists of the traditional business areas, the administrative centre, and the Central Business District. Basic infrastructure (acceptable road system and water conveyance), in the core areas is reasonably good – particularly in the south and west part of the city, from the industrial zone of Peenya to Koramangala. This space also has a large distribution of mixed housing/commercial activities.

- 2nd Zone – The Peri-central area has older, planned residential areas, surrounding the core area. This area also has reasonably good infrastructure, though its development is more uneven than the core area.

- 3rd Zone – The Recent extensions of the City (past 3-5 years) flanking both sides of the Outer Ring Road, portions of which are lacking infrastructure facilities, and is termed as a shadow area.

- 4th Zone – The New layouts that have developed in the peripheries of the City, with some vacant lots and agricultural lands. During the past few years of rapid growth, legal and illegal layouts have come up in the periphery of the city, particularly developed in the south and west. These areas are not systematically developed, though there are some opulent and up-market enclaves that have come up along Hosur Road, Whitefield, and Yelahanka. The rural world that surrounds these agglomerations is in a state of transition and speculation. This is also revealed by the “extensive building of houses/layouts” in the green belt. Both BDA and BMRDA are planning to release large lots of systematically developed land, with appropriate infrastructure, to address the need for developed urban spaces.

- 5th Zone – The Green belt and agricultural area in the City’s outskirts including small villages. This area is also seeing creeping urbanization. While the core area has been the seat of traditional business and economy (markets and trading), the peri-central area has been the area of the PSU. The new technology industry is concentrated in the east & southeast. These patterns are obviously not rigid –especially with reference to the new technology industry and services that are light and mobile, and interspersed through the City, including the residential areas. Table 9.2 provides the current land use pattern in BDA area

While infrastructure in the City is reasonably good in some aspects (water and sewerage, for instance), it is under stress in other aspects, particularly urban transport. Qualitatively, the urban infrastructure situation is profiled in the following:

- Water supply: The availability of raw water at about 140 lpcd is adequate, though the draw distances are increasing progressively. UFW is high, and distribution is uneven – being better in the BMP areas and poor in the peripheral areas.

- Storm water Drainage: Drainage is an area of concern, with the natural drainage system (Valleys) being built upon. With the growth of the City, the number of lakes has dwindled, and small lakes and tank beds have vanished because of encroachment and construction activities. This has resulted in storm-water drains reducing to gutters of insufficient capacity, leading to flooding during monsoon. Dumping of MSW in the drains compounds the problems, leading to blockages. To control floods, it is important to remove silt and widen these storm water drains to maintain the chain flow and avoid water from stagnating at one point.

- Transport: Rising traffic congestion is one of the key issues in the City. Though the length of roads available is good, the problem lies with the restricted widths. BMTC is one of the best bus transport corporations in the country, but the absence of a rail-based commuter system compounds the problem.

- SWM: Collection and transportation coverage is very good, but proper and adequate treatment/ disposal facilities are lacking.

- Green Areas & Water bodies: The City has a tradition of being a “Garden City” with plenty of green spaces and water bodies. However, the very high growth rate in the past two decades is having an adverse impact on these.

Key Issues of Urban Drainage Systems

Urban drainage has a direct impact on the City's image, citizens' life, and health. If the system does not work properly, it leads to environmental hazards (CDP, 2006). Improving the urban drainage system requires not only capital infusion, but also recurring expenditures for operation and maintenance. A single point obstruction in a storm-water drain would have a cascading overall impact. Citizen awareness is therefore a critical issue, and citizens and non-governmental organizations can play a key part in monitoring development in the region to ensure that drainage is not obstructed, and dumping of debris and MSW in drains does not occur.

Adherence to best practice guidelines as pre conditions to issuing a permit for development will help to ensure that all development within the city contributes positively to the maintenance of water quality, structural stability, hydraulic capacity and environmental and ecological values of the City's waterbodies. This includes:

- the protection and enhancement of the good water quality of the waterbodies and the improvement of areas of degraded water quality;

- the maintenance of the structural stability and hydraulic and flood carrying capability of the cities waterbodies;

- the protection of the water supply function (i.e. for irrigation) of the City's existing catchments, waterways and lakes;

- the inclusion of appropriate storm water quality and quantity management in the planning and design of developments; and

- the provision of adequate space for stormwater quantity and quality management infrastructure and the utilisation of existing features of the site such as drainage lines and waterbodies, in the design of the development and stormwater layout.

Suitable measures to assist in maintaining the pre-development storm water discharges include; retention/detention basins as part of a storm water treatment, increase in pervious areas on the site, the use of porous materials in those areas normally surfaced (such as footpaths); and the inclusion of on-site detention storage tanks with the design of multi-unit/building developments. The objectives of an urban drainage system should include:

- No encroachment of the designated waterway area or reduce the waterway area or obstruct the flows by filling in the floodplain

- Ensuring habitable buildings are not flooded in major storms (i.e. 5, 10 or 25 year Average Recurrence Interval (ARI) or as appropriate).

- Flood waters do not present an unacceptable risk to personal safety in major storms (i.e. 5, 10 or 25 year ARI or as appropriate).

- Underground drains with sufficient capacity to ensure that flooding is not a regular nuisance in minor storms.

- The risk of pollution of drains and waterways minimised by preventing sewage discharge to storm water, by managing the storage and discharge of hazardous materials, by controlling land use and by reducing the major sources of pollutants.

- Drainage and waterways must be considered in the development of a strategic plan for future development including:

- protection of waterways by incorporating open space as a designated waterway corridor in the City Plan. This will reduce future building encroachment and subsequent flooding; and

- any developments in the stormwater catchment will increase flooding and potential pollution of downstream. These issues should be considered in the planning stage, especially in cases where flood mitigation options are limited in the downstream system.

Drainage lines can contribute substantially to the landscape and open space amenity of development. A decision needs to be made as to the appropriate land take for drainage areas and the style of waterways to be adopted. Key actions required are:

Core Area Drain Rehabilitation: A broad approach towards correcting the more severe problems would involve work on cross drainage, cross services and sewers in manholes, together with new drains and wall replacement. Such works would be followed by the correction of severe – but more problematic – drain deficiencies. That may involve land resumption and major construction of walls. Approximately 81 km of main sewers are laid in drains. At least 20 km of these sewers are in need of replacement for capacity reasons. Additional lengths may have to be replaced for condition or other reasons. Similarly, drain improvements will require modification of these sewers. Total relocation of sewers out of drains is not essential and it is proposed that wherever a sewer needs to be replaced, consideration be given to relocation into adjacent roads or reserves. Of those sewers that will remain in drains, the vast majority should have their manholes modified to avoid flow obstructions. Sewer leakage and direct discharge to drains is to be addressed under the sewerage rehabilitation program.

Scheduled Drain Clearance: Until such time as drain inverts are redesigned for self-cleansing velocities and solid waste programs are implemented, ongoing regular clearance of drains is necessary to minimise flooding risks.

Even when drain upgrading as well as improvements in solid waste collection are completed, there will remain a need to remove silt and litter from the drains and inlets to tanks. In the longer term, catchment management practices which control silt loads from erosion sources will also need to be implemented.

Water Quality Improvements: At present, the principal causes of poor water quality are the sewage flows and large solid waste content in the drains. The sewer rehabilitation program would involve sewerage of unsewered premises (including those directly connected to drains); repair of sewer leaks; and upgrade of sewer capacity.

Capacity building: Training of drainage practitioners, operating within private and government organisations, is needed in a range of main drainage activities, including rainfall trends analysis, run-off estimation for small catchments, run-off estimation for larger catchments, using hydrograph techniques, hydraulic analysis of channels, culvert and pipes, using basic and backwater techniques, planning and design for major and minor drainage systems; and powers and duties relating to drainage and planning legislation.

Land Use and Development Controls: Review of regional planning, including the Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Authority (BMRDA) structure plans and the Comprehensive Development Plan (CDP) to include drainage policy, provision for identification of flood-prone lands and control of its subsequent development, creation of wide reserves and easements for primary and secondary drains and control of development in the floor of primary and secondary valleys with respect, at least, to building floor levels and set-backs from reserves. In implementing land use and development controls and in enforcing legislation, consideration needs to be given to the special needs of the urban poor who are likely to bear the disproportionate burden of such measures.

Legislation and Institutional Reforms: A comprehensive review of the institutional arrangements for management of primary and secondary drainage within the BMA is desirable, with a view to creating one single drainage authority with the responsibility for identification of flood-prone lands and flood levels, approval of development plans for layouts with respect to flooding and drainage, planning of all waterways and drainage, integration of waterways and drainage with urban land use planning, including identification of easements, setting of levels of service for all secondary and primary drains and lands adjacent to tanks, in conjunction with all stakeholders, preparation of integrated drainage plans for each main catchment; and Monitoring of development and advising planning authorities on non-complying urban development.

The roles of implementation and operation could be undertaken within existing and strengthened municipalities and/or an expanded BMP.

Education and Consultation: Environment education programs through schools, colleges, NGO’s and mass media to raise community awareness and understanding of the risk of flooding, the importance of clean waterways and their role in supporting community well being, health and the overall life style in the city of Bangalore.

Best management practices (sediment fences, re-vegetation, sediment barriers, graved channels, dimension channels, etc.) for erosion and sediment control to manage development activities in a catchment, and involves:

- Erosion Control – the process of minimising the potential of soils to be eroded and transported in the first instance through the effects from wind, water or physical action through surface stabilisation, revegetation, erosion control mats, mulching, surface roughening, etc. These techniques represent a source control in preventing erosion of the soil material in the first instance.

- Sediment Control – the process of minimising the transport of eroded material (sediment) suspended in water or wind through catch drains, check dams, lined channels, grassed channels, and diversion channels, drop pipes, chutes and flumes.

In Bangalore, the sources of sediment supply to the drains include wash-off and erosion of unvegetated median strips, walkways and parklands, litter from trees and other vegetation, wash-off from roadways and impervious areas, wash-off and erosion from unmade roads and partially developed layouts, erosion of steeper unlined drains, construction site erosion or drainage water, drainage channel erosion and solid wastes dumped directly into drains or washed from pavements.

Key activities implemented for improvement of SWD

The key activities for improving storm water drains in the city included construction and rehabilitation of roadside drains, remodeling and strengthening, clearing silt, constructing of walls, laying of beds, provision of enabling and awareness information architecture and green area development. The action plan included:

- Clearing all encroachments that come in the way of the storm water drain network in the city (Plate 5.1);

- Aligning the drain network and checking blockage and overflowing of drains; Removing silt (Plate 5.2, 5.3, 5.4 and 5.5);

- Construction/remodeling/rehabilitation of road side drains (Plate 5.6 and 5.7) - Constructing 1,500 km of roadside drains (cost of construction assumed at Rs. 30 lakh per km for a 5-metre drain);

- Decreasing the load on Koramangala storm water drain (originating from Majestic and flowing into the Bellandur Lake) by building a bypass box canal from this drain via Agaram to the Bellandur Lake;

- Constructing a similar bypass canal via the Karnataka Golf Association; Reviewing existing storm water drains, ensuring connectivity of primary, secondary and tertiary drains;

- Constructing retaining walls (Plate 5.8);

- Redesigning for current load conditions along with building barriers between roads and open drains at crossings (Plate 5.9 and 5.10).

- Restoration and conservation of waterbodies (Plate 5.11)

- Laying of beds (plate 5.7);

- Remodelling of storm water drains (Plate 5.12 and 5.13);

- Provision of enabling and awareness information architecture; and

- Green area development.

Plate 5.1: Removal of storm water drain encroachments in Nayandahalli, Bangalore (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.2: Removal of solid waste from the drain in KH Road, R.R. Nagar (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.3: Removal of blockage in Kalappa layout (Source: BMP)

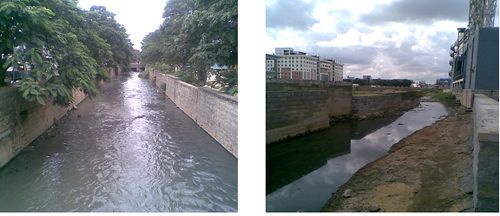

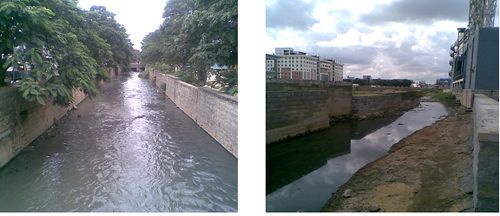

Plate 5.4: Desilting in Koramangala main valley, KH Road and Chalgatta valley (source: BMP)

Plate 5.5: After desilting - Koramangala Valley, Vajapayee nagar

Plate 5.6: Construction of RCC box drain in Puttenahalli (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.7: Remodelled storm water drain

Plate 5.8: Storm water drain retaining wall construction (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.9: Chain link fencing to prevent solid waste dumping (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.10: Providing screen in storm water drain

Plate 5.11: Restoration of Ulsoor lake with STP (Source: BMP)

Plate 5.12: Redesign of storm water drain (Source: BMP)

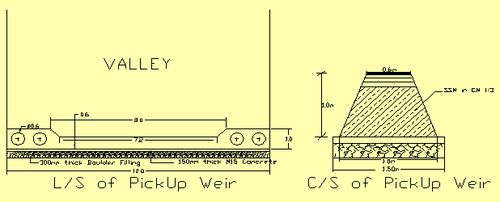

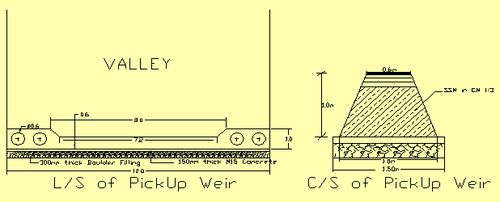

Plate 5.13: Design of pickup weir (source: BMP)

The City is proposing to have a coordinated action plan to address the issue of urban drainage. At present BMP is coordinating the “valley projects,” and is carrying out the works in coordination with other agencies, facilitated by the GoK.

Compounding the flooding problems are the unsanitary conditions created by large volumes of raw, or partially treated, sewage and large volumes of solid wastes entering the drainage system (Plate 5.2 and 5.3). Strategic options for rehabilitating and extending the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB) sewerage system and for expanding the BMP (Bangalore Mahanagara Palike) solid waste management system have been prepared. Following filing of writ petitions in 1999, and subsequent issuance of High Court Orders against the Government of Karnataka (GOK) and several authorities in Bangalore responsible for provision of environmental sanitation services, an Environmental Action Plan was devised to address the worst of the existing problems and remedial actions, including desilting of drains, have been completed in some localities (Plate 5.3 and 5.4).

The potential values and importance of waterways in the urban environment have been undermined consequent to fragmented management arrangements. Similar fate might befall the waterways in the rapidly developing lands within the Bangalore Metropolitan Area (BMA), but outside of, and downstream of, the BMP catchments. The critical issues that is to be addressed relates to the fact that inadequate drainage in a particular ULB jurisdiction may not have the impact in that ULB but elsewhere. Coordination and continuity of action between the ULBs is of critical importance. Strategies for improved service delivery include:

- The importance of inter-ULB and Agency coordination:

- Inadequate drainage in a peripheral ULB may impact drainage in BMP areas;

- Improper drainage of BWSSB’s system may pollute the valley system and impact quality of life across the City; and

- Improper roadside drainage and cross-connectivity may similarly impair system performance;

- Citizens to be involved to monitor contractor's activity on clearing of drain systems in their area:

- Citizens who dump debris into storm water drains could be penalized; and

- Removing silt to be a regular activity before the monsoons starting with the main (primary) drain.

Drainage management plans (DMPs) for each catchment are required to enable all deficiencies identified, an affordable level of service developed, all upgrades designed to a consistent standard and priorities set for implementation. Action plan suggested in this regard are listed in Table 9.3.

Table 9.3: Drainage Management Action plan

| Objective |

Action Areas |

Summary of Measures |

| Manage the Flood Risk |

| Minimisation of the impacts of flood events and potential damage costs |

Existing development (core area and outer area) |

Introduce flood mitigation structural measures, (restriction removal, widening/deepening)

Remove illegal encroachments

Develop and implement awareness programs |

| Proposed development (core area and outer area) |

Control land use, development

Develop and implement awareness programs |

| To collect and provide best available data for managing the flood risk |

Develop spatila information system with an up to date Topographic, land use, hydrologic, flood impact data, etc. |

Identify flood-prone areas, flood levels

Collect flood impact information

Conduct topographic surveys |

| Control Land Use Planning and Development |

| Integrating urban storm water drainage functions in CDP |

Land use planning |

Amend planning legislation and regulations if necessary

Incorporate drainage policy into structure and consolidated development plans (CDP)

Provide drainage reservations in planning schemes |

| Development controls |

Impose development controls (filling levels, floor levels, reserves, set backs) for each drainage authority/municipality |

| Monitoring and enforcement |

Monitor encroachments and floor levels

Enforce policy and regulations |

| Implement Effective Asset Operation and Maintenance |

| To manage the urban storm water drainage assets economically and to protect public health and safety |

Drain siltation and litter |

Schedule and perform regular drain clearance

Support solid waste strategy (at source collection)

Trap gross sediment on tank inlets |

| Asset condition monitoring and maintenance |

Schedule inspections and audits of drain assets

Conduct safety audits of tank embankments and spillways

Prioritise maintenance activities

Coordinate other infrastructure assets |

| Construction standards |

Develop design, construction and maintenance standards to reflect economic life cycle asset costing

Apply construction standards through appropriate supervision and QA systems |

| Drain safety |

Erect warning signs, fencing, etc., where appropriate

Minimise safety risks in design |

| Enhance the Environment and Social Conditions |

| To expand and protect the social and environmental amenity of open urban waterways, where possible |

Social equity |

Promote community based representative decision making

Set basin wide drainage levels of service

Target improvement works according to agreed priorities |

| Cultural and heritage |

Restore water quality in tanks (drainage system)

Desilt tanks

Develop and implement education programs within an overall communications strategy |

| Recreation/landscape |

Restore tanks

Landscape riparian lands

Provide access and linkages along drainage corridors |

| Aquatic environment |

Provide in-stream features (water falls, swales, wetlands)

Introduce water quality improvement actions

Use alternative waterway design |

| Improve Water Quality |

| To improve the quality of water in the drains and tanks |

Sewage entering stormwater system |

Extend sewerage system

Repair sewer leaks

Upgrade sewer capacities |

| Litter & solid wastes |

Collect solid wastes

Develop and implement education and awareness programs |

| Stormwater quality improvement |

Enforce appropriate stormwater and catchment management practices (erosion control, litter and silt traps, street sweeping) |

| Provide Supporting Drainage Legislation and Regulations |

| To provide effective drainage regulations and management arrangements |

Drainage authority |

Review roles and responsibilities of authorities involved in drainage and provide effective mechanisms for drainage planning, implementation, monitoring, enforcement and funding |

| Land use planning |

Amend structure plan, CDP to reflect drainage policy |

| Building and development controls |

Amend municipal and planning legislation to provide adequate controls over land filling, floor levels etc. |

| Prioritise Resources & Actions |

| To provide adequate funding and resources for capital and recurrent activities according to agreed priorities |

Priorities and funding |

Collect supporting flood damage data

Prepare integrated drainage management plans

Consult with stakeholders on priorities

Introduce general drainage tariffs

Introduce development contributions to main drainage

Allocate appropriately government grants and loans

Use lending agency loans |

| |

Training |

Train practitioners in drainage management methodologies and techniques |

Progress during 2008-09

The torrential rain of May 2006 crippled almost the entire city. Posh residential layouts, poor low-lying slums and even the busy streets such as Mahatma Gandhi Road and Vidhana Veedhi were affected. While parts of Jayanagar went without power for three days as the junction boxes were damaged following the rain, Church Street, Shantinagar, Rest House Road were inundated in knee-deep water. The impact of the rain in areas such as Ejipura, Jogupalya, Jeevanabimanagar, Murgeshpalya, parts of Sampangiramnagar and surrounding areas was devastating. During 2006 monsoon, people used boats to cross the road in this locality because of flooding of water. The water logging happens when the intensity of rain is high and whenever the flow of water into the drains is more than the discharge capacity. Several areas in the surrounding suburbs such as Puttenahalli, Pai Layout, HSR Layout and Bommanahalli were the worst-affected last year. That was because these areas did not have a stormwater drain network and, moreover, they had encroached upon lake-beds.

Traditional storm water management techniques simply collect the rain water and funnel it across the city downstream. Newer methods combine traditional approaches with new ones such as Sustainable Drainage Systems (SUDS). It employs a range of natural processes to purify urban runoff. Removal of sediment, bio-filtration, biodegradation and water uptake by plants all help to remove pollutants. The city needs many such recharge wells in the catchment area of critical flood zones to detain flood waters and top up the aquifers instead of surface flow flooding. At the broader scale, tanks and lakes need to be networked and managed as retention and detention structures. With rainfall prediction accuracy being developed, tanks have to be linked to catchments and kept ready to hold the maximum water to dampen peak storm events. A deslited tank in Bengaluru can recharge up to 11 mm of water every day while an undesilted one can recharge hardly 1 mm. Desilted tanks can recharge aquifers quickly, lower the surface water levels and be in a position to function as flood mitigators. Full tanks are not good at dampening floods.

The Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) during 2008-09, focused on providing permanent solution to overflowing of storm water drains, water logging, and other related problems during rains. BBMP built a new storm water drain to prevent flooding in Bandeppa Colony. Similarly, a storm water drain was widened besides raising the height of retaining walls. BBMP was successful partially in evicting the encroachers of storm water drains as owners of buildings, built on the raja kaluve, had obtained stay orders from courts. The BBMP demolished 10 structures covering 600 sq.m. of drain area in Bhadrappa Layout in Hebbal. These structures had come up on the storm water drain leading to the Hebbal Lake. Work on increasing the height of retaining walls of storm water drain and providing gradient to shoulder drains at Bhadrappa Layout were in progress and the situation was likely to improve once the works were completed. BBMP established control rooms, including the zonal control rooms. The control rooms were fully equipped with men and material. Of the 280 identified vulnerable areas, 48 had been marked under “A” category and four of these are under “A+” category (the region highly vulnerable). The Central Silk Board area, Puttenahalli, Arakere, Nayandanahalli, Katriguppe, Illyas Nagar, Bhadrappa Layout, S.T. Bed Layout, Kamakhya Layout, Hennur, Ejipura and Bandappa Colony are these vulnerable spots.