Scared Groves: Vital Ecosystems to Sustain Local Livelihood in Goa

T V Ramachandra, and Prachi

Singh

IISc-EIACP, Environmental

Information System, CES TE-15

Indian Institute of Science,

Bangalore 560012

E Mail:

tvr@iisc.ac.in, envis.ces@iisc.ac.in, Tel:

91-080-22933099/

23608661

Introduction

The early period of civilization witnessed the clearing of forest land for settlement and cultivation. Conservation of forest patches with rich flora and fauna is practiced (Rajasri et. al. 2014, Chandran et al. 1998) with worshipping of inanimate deities in various ways across different regions in the world, and these patches are known as Sacred Groves (SGs). The spatial extent of groves varies from small patches to larger areas, which are dedicated to the local deity, with the stringent protection measures evident from the occurrence of native vegetation without any disturbances (Gadgil & Vartak 1981), and groves are found in every habitable continent. The practice of conservation through sacred groves is an informal way of protecting the natural vegetation by the local people. (Bhagwat & Rutte 2006), which are evident from the presence of climax vegetation with a rich repository of biodiversity, which are conserved through traditional practices and beliefs. Native flora has been an important part of the culture in India since the Vedic period, and forests were preserved and maintained by promoting utilitarian aspects of productivity and protection. Vedic norms prescribe protection of native vegetation of great ecological values, which benefit society (Mushtaq et al. 2023). Many tree species are being preserved through this age-old conservation system, which is evident from the occurrence of relic species. IUCN considers sacred groves as “areas of land or water having special spiritual significance to peoples and communities” (IUCN 2008), and are conserved under sacred natural sites (SNS). Sacred Groves are an ideal example of the practice of biodiversity conservation by the community, which signifies the importance of biodiversity among the native people, who are directly dependent on the regional forests for livelihood. Local traditional communities have developed a deep understanding of the natural phenomenon with time and experience as they have always been close to nature.

Sacred groves provide natural habitat to several species of flora and fauna and are home for several rare and endangered species and aid as a gene pool of the native biodiversity (Ramchandra et al. 2012). SGs association with waterbodies like ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers helps in watershed protection (Subash et al. 1998), maintains a favourable microclimate in the area, protects the area from fire having mixed vegetation including evergreen forests which helps in avoiding fire (despite having a thick layer of fallen and decayed leaves, stems etc.), bind soil which helps in mitigating soil erosion (Ramchandra et al. 2012).

The spiritual significance with taboos and beliefs of SGs in the native people has ensured the protection of trees and other living and non-living things in the region. People have a strong belief in the spirit of the sacred grove, which has promoted a positive relation to the protection of the SG. Small shrines or temples are built at the entrance of SGs in Goa, where people give offerings to the deity when their wish is fulfilled. The native people do not have a tradition of owning the land and consider SGs as the property of a deity (Ramchandra et. al. 2012). Although now it is protected only due to fear of deity, rather than high value of ecological and hydrological services with rich biodiversity and aid as a carbon sink to minimise local carbon footprint.

Deterioration and decline in SG are observed in several parts of India due to the erosion in environmental knowledge and cultural beliefs, with the arrival of colonial commercial voyagers - Portuguese in Goa and Britishers in India, challenging the religious belief of native people, which resulted in undermining, the worth of forests and helped the exploitation of forests for commercial purposes ignoring it’s much more precious ecological benefits, and the exploitation continues which have been threatening the sustenance of the natural biodiversity. These anthropogenic activities leading to over-exploitation of natural resources have resulted in the extinction of many species being endemic of the region (Ramchandra et. al. 2012). Considering the numerous ecological services provided by the sacred forests necessitate conservation on priority to sustain the livelihood of local people. The local conservation practice, which has become a socio-cultural norm for native people, has sustained the natural system of biodiversity while managing the environmental and ecological balance of the area. Thus, sacred groves constitute the bridge between society and nature, which illustrates the dependency of humans and living symbiotically with natural ecosystems (Sakshi et al. 2021).

Literature Review

Culturally important SGs have proved to be an invulnerable system for biodiversity conservation in various regions of the world, including India. Sacred groves are distributed all over India and are majorly found in Khasi and Jaintia hills, Aravali hills, Western ghats, Bastar, Khecheopalri lake, which are informally protected by the local communities except for the few protected areas by the government. Literature pertaining to sacred groves in different regions of India highlights the significance of Sacred Groves from a biodiversity point of view and the conservation challenges in recent times.

The Western Ghats, one among 36 global biodiversity hotspots and recognised as UNESCO World Heritage site, is home to numerous SGs, which are known by different names - Devrai (in Maharashtra), Kans (in Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka), Devarakadu (in Western Ghtas districts in Karnataka), Kauvu (in Kerala), Rai (in Goa) Rai, Kovil (in Tamil Nadu), etc.

Literature on the Western Ghats region provides plenty of information on the species available and the challenges faced in the survival of those species due to human interference. Many rare and ethnobotanically essential species are found in the Western Ghats, such as endangered species (Pinanga Dicksonii, Semicarpus Kathlekanansis, Gymnacranthera Canarica, Syzygium Travancoricum) of Mystrica Swamp in Katlekan of Uttara Kannada (Chandran et al. 1998; Rajashri et al. 2014) and two villages of Sattari taluka in Goa. Other endemic species (Rajshri et al. 2014) found in SGs of Uttara Kannada are Syzygium Travancoricum, Actinodaphnae malabarica, Beilschmiedia bourdillonii, Cinnamomum malabatrum etc., and are not found outside the SG, which proves that SGs have rare and endemic plant species along with the high level of biodiversity that is often higher than the surrounding area (IUCN 2008) which are of great value in terms of ethnobotanical uses, due to its biodiversity, and that’s why not only in India but in many other countries this tradition of conserving natural resource prevails. (Sakshi et. al. 2021). Most of the species found in SGs have medicinal usage and have been used by the natives since ages for treating various diseases.

Moreover, plants listed by IUCN in the red list as endemic, extinct, etc., are found in the sacred groves and can be used to regenerate more plants and trees. Still, the rare species among sacred groves are also in danger of extinction due to extensive human interference and need necessary attention and conservation measures for protection (Ramchandra et al. 2011). Due to human interventions, land use around the SGs has changed drastically over the years and has resulted in converting vegetation-rich areas to cultivable and residential land, resulting in degradation. Large-scale land cover changes with decreased forest cover and increased built-up and cropland from 1989 to 2010 were due to human interference (Rajshri et al. 2014). Similarly, a study on Kan forest of Shimoga district shows fragmentation of native forests due to over-exploitation of resources by contractors and pressure of development (Ramchandra et al. 2012). Colonial regimes curtailed the rights of native people and penalised local people with tax for collecting forest products, due to which native people are often seen as the exploiters of the forests instead of protector. Policies are also made, which affected the livelihood of the local people and allotted forests to contractors who practiced commercial exploitation, ignoring the ecological health of the groves. The cultural importance of Sacred Groves has a major role in its protection by the local people with the acceptance of such informal conservation among the community, which the authorities should have considered for the protection of the area (Bhagwat & Rutte 2006).

Policies and ownership of sacred groves in India vary from region to region as more community-owned SGs are found in Meghalaya compared to the Kodagu district of Karnataka, where the revenue department is the custodian of sacred land (Ormsby 2011). Community-owned lands are comparatively better preserved than state-managed systems, but combined efforts need to be made for the protection of such natural sites. Also, community protection is truly based on cultural values, which always change with time, and many SGs have witnessed the deterioration due to the weakening of cultural values among communities in recent times, which necessitate appropriate policy strategies for the conservation of ecologically fragile regions.

A study in Baitadi, Dadeldhura, and Darchula districts of Nepal suggests increased anthropogenic activities leading to the loss of medicinal plant species and degradation of forests due to unsustainable practices by the residents with an increase in temperature. Unplanned developmental activities driving land use changes with enhanced CO2 contribute to the deterioration and extinction of plant species, changes in the climate, etc. (Ripu et. al. 2018, Rajesh et. al. 2016). An increasing threat to the SG is witnessed in most parts of India, leading to the decline of biodiversity with urbanisation, which is affecting native people who as stakeholders, have been protecting and are dependent on the forest for medicinal, livelihood, and other purposes. As a result, slowly, with modernisation and urbanisation of the area, the belief system of native people has started to erode, resulting in the loss of knowledge of ethnobotanical plants, cutting of trees, and unregulated use of resources. It is observed that temples near SG usually have water bodies, which aid in recharging the underground water, which was used only in the case of water shortage by the local people. The potential of SG to mitigate consequences due to changing climate necessitates perseverance of native species forests for water security as waterbodies are perennial in SG with a higher proportion of native species compared to waterbodies in the degraded catchments.

The first global agreement on the conservation of biological diversity was in the 1992 Earth Summit, which had an agreement on convention on biological diversity (UNDP India 2008) and preserving SGs would be an important step to achieve such goals considering the community support in maintaining biodiversity, which is independent of any authority. The government of India, with UNDP, has taken initiative of conserving biodiversity through community-based resource management in Arunachal Pradesh, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Jharkhand, including reviving two Sacred Groves in Arunachal Pradesh and livelihood protection of the people (UNDP India 2012).

Considering the ecological and social significance of sacred groves, IUCN and UNESCO have provided a guideline for the management of sacred natural sites (SNS), such as inventorying, mapping and integrating SNS into the planning and management programmes, prioritizing participation of the stakeholder and respecting their rights over the sacred natural sites, encouraging proper knowledge and understanding which will help in protecting the SNS with proper management (IUCN 2008). As local communities protect these groves for their cultural values, unaware of the ecological benefits of these areas in most cases, there have been land use changes involving the construction of temple buildings around the deity, ignoring the flora and fauna of the region (Ankur et. al. 2021; Chandran et. al. 1998).

A study in Satwani of Maharashtra found that the land around sacred groves is mostly used for cultivation and is expanding slowly, risking the forest. It was observed that land owned privately by the local community consists of higher native vegetation cover compared to the forest department-managed SGs (Pooja et. al. 2021), which shows the positive side of the scenario. The migration of younger generations to urban areas and subsequent erosion in their faith in traditions and cultural shift in belief system has resulted in the degradation of sacred groves.

Climate change-driven escalating temperature and acute water scarcity in various regions of the world have necessitated sustainable management of natural resources, particularly sacred grove ecosystems, which play a vital role due to their acceptability among locals. Also, the ecosystem found in the groves is unique and has been protected by local communities, showcasing the example of the human-nature relationship that has prevailed and survived for centuries even after so many cultural changes over time due to various factors (Ankur et al. 2021) which shows its high acceptability among people.

Cities that are developed on the native land may find such regions, Cape Town in South Africa has Table Mountain in the middle of the city, which is considered sacred by the people, and Shinto shrines in Japan are the sacred green spaces and are worshipped by the people (Wendy & Ormsby 2017). Many more such sites can be found in the urban landscape, which can act as a green space for cities with rich biodiversity. Sacred Groves in Yoruba cities in Nigeria, used as isolation centres during the time of epidemic or contagious diseases in ancient times, was also used during the recent pandemic of Covid 19 (Ogundiran 2020). However, unplanned developmental activities leading to the rapid urbanisation and advancement of the society have contributed to the decline of the traditional knowledge and natural wealth of the country. The focus on economic growth as a developmental measure often hinders ecologically prudent management of natural resources (Borkar 2006).

A study of nine sacred groves in Hong Kong categorized the trees in restricted, rare and very rare category. Very rare category consists of Litsea elongate, Aphananthe aspera, Jasminum elongatum, Illigera celebica, Ilex chapaensis, Liquidambar gracilipes, Magnolia figo. (Lee et. al. 2023) and rare trees in fung shui woodlands. The reason for their degradation is migration of indigenous villagers to urban area and conversion of surrounding villages into peri urban region, affecting the biodiversity of the area, which highlights the cultural significance of protecting SGs.

The current issue of Sahyadri E News (Issue LXXXVII) presents sacred groves of Goa State with details of plant diversity.

Materials and Method

Study Area

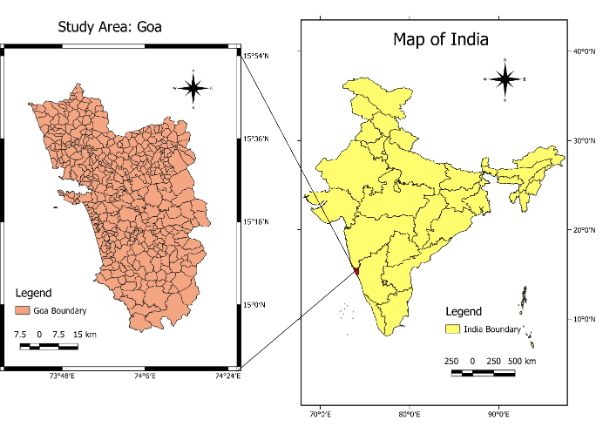

Goa, the smallest state of India stretches between 14º 53’ 57’’ N to 15º 47’ 59’’ N latitude and 73º 40’ 54” E to 74º 20’ 11” E longitude (Figure 1) with the geographical area of 3702 km2 extending for a length of 105 km from north to south and breadth of 60 km from east to west with the coastline of 131 km. Goa is situated at the west coast of India along the Malabar coast between the Arabian Sea on its western margin and the Western Ghats on the eastern margin from Salginim to Surla Ghat. On its northern boundary is Maharashtra, and the southern boundary is Karnataka and Arabian Sea on the west and the Western Ghats (Sahyadri mountain ranges) on east.

Goa is often called a tropical paradise due to its location, which provides a warm and humid climate. This climate helps to nurture several indigenous species of trees, which are important for maintaining the biodiversity of the area. Major rivers in Goa are Mandovi, Zuari, Terekhol, Chapora, and Sal among these, Mandovi and Zuari are the largest. It is believed that there are three hundred or more old water tanks built during Kadamba rule, along with this, around hundred springs are there having medicinal properties. Population of Goa is 1.82 million. Capital of the state is Panaji, and the state is divided into two administrative districts, north Goa and south Goa, and the state is further divided into twelve talukas in north Goa - Bardez, Bicholim, Pernem, Ponda, Sattari, and Tiswadi, and in south Goa - Canacona, Mormugao, Quepem, Salcete, and Sanguem. The most widely spoken language is Konkani.

Figure 1 Study area: Goa

The climate of Goa is warm and humid tropical, with an average rainfall of 2800 mm received from the southwest monsoon. The temperature during summer ranges from 24 °C to 36 °C and during winter, 21°C to 30 °C. Forest types of Goa range from evergreen to semi-evergreen including deciduous, and estuarine vegetation in the coastal area. Soil type is extensively lateritic with sandy loam to silt loam texture, few amounts of soil is alluvial in nature.

The major occupation of people in Goa is agriculture, tourism, and fishing. Goa being situated on the coastal area with a high number of beaches, attracts a large number of tourists, which is a major source for SDP in the state, but it also poses challenges for losing the states cultural and religious values. Being part of the Western Ghats, Goa is rich in biodiversity and is home to many sacred groves with high cultural and ecological values.

Method

The information pertaining to Sacred Groves was compiled from (i) field investigations and (ii) published literature, including (a) the book “Sacred groves of Goa” by Rajendra Kerkar, which aptly describes the SGs of Goa, and (b) Sacred Groves of country by CPREEC (C.P.R. Environmental Education Centre). The spatial distribution of sacred groves is developed using Google Earth (https://earth.google.com) through QGIS (https://qgis.org).

Results & Discussion

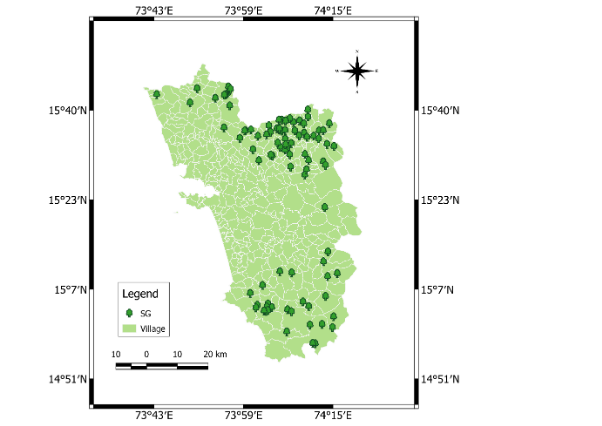

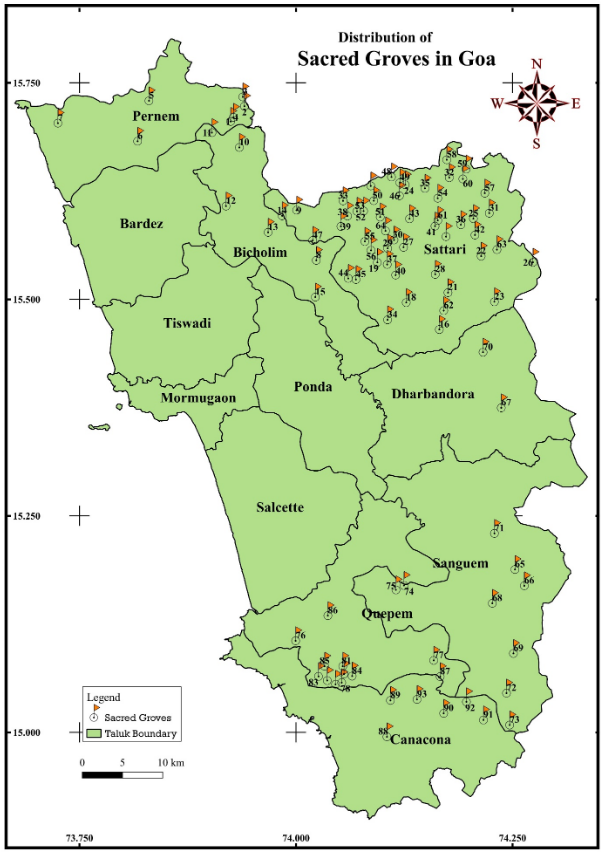

Goa ranks 3rd in the social progress index in the country, with 65.53 SPI, which indicates that the state's high development is in tune with urbanization and land use changes. The state is having a large amount of Western influence but still preserves native culture in various forms. The culture of Goa is a mosaic of several influences, but it does not lose its origin. The state is a mix of Catholic and Hindu culture, which is experiencing transitions as Goa is a tourist spot for many people. Being in proximity to the Western Ghats, Goa is home to many SG of high biodiversity and cultural value known as Devrai, Pann, Devaran in the local language, each of the SG having its folklore and myths as an integral part of their culture through which they are protected from ages. Sattari taluk in North Goa consists of the highest number of SG among all (figure 2), and it is situated in the northeast of the state consisting of the protected area Madhei Wildlife Sanctuary in the Sahyadri mountains protects the area from urban land use change helping in the maintenance of large number of SG.

Traditionally, a deity is associated with the SG in Goa, which is considered the protector of the village and is respected by all, irrespective of the community. Villagers believe that doing something against the will of the deity may lead to certain consequences. The villagers strictly follow regulations, such as abstaining from taking fallen stems of trees from the grove, which protects the natural harmony of the area. A few of the sacred groves of Goa with large areas are Ajobachi Rai, Baldyachi Rai, Comachi Rai, Birmanyachi Rai, Panvelichi Rai, Hornyachi Rai, Oralachi Rai, Pishyachi Rai, Abadurgyachi Rai, and Maulichi Rai located in Vagheri of Sattari in Goa. (Kerkar 2009). There are many more such sacred groves that have been protected by the local communities for ages, conserving the biodiversity of the area, but are now being destroyed and degraded by the authorities. The taboos associated with the groves have weakened over time, leading to their degradation, with lifestyle changes due to modernisation of the society and migration of the younger generation to urban areas. Worship of trees has been a cultural tradition in every part of India in different forms and has helped protect the natural biodiversity. Trees such as peepal (ficus Religiosa), Shami (Prosopis cineraria), Tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) are commonly found in temples in Goa, and numerous sacred plants and trees can be found in and around houses. The cultural values of the people have aided in the ecological protection of important indigenous species.

Efforts by the local with the help of the state government have resulted in the protection of a sacred grove at Bicholim (Purvatali Rai), which is given the status of a biodiversity heritage site under section 37 of Biodiversity Act 2002. Biodiversity heritage sites are areas with fragile ecosystems with unique biodiversity and rare species of medicinal plants. The bicholim landscape is experiencing land use transitions due to numerous mining activities. Hence, the protection of biodiversity conservation, restricting the overexploitation of natural resources, and cultural perseverance gained significance. The “State Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan” also includes sacred groves and water resources.

Figure 2 Distribution of SG in Goa

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of Sacred Groves in the Goa, which indicates that most SGs are located in the vicinity of the Western Ghats and the majority of them are located in the eastern Maharashtra border. Table 1 lists the prominent plant species in the sacred groves of Goa.

Table 1 Prominent species in Sacred groves of Goa

|

Village |

Sacred Grove |

Prominent species |

|

Ibrampur |

Pirapeth of Angodwada |

Indian Fishtail or Sago Plant (Caryoto Urens) |

|

Virnoda |

Nagardeshwar |

Ficus Bengalensis, Garcinia Indica, Syzigium Cumini |

|

Cudnem |

Devachi Rai, Kumbharkhanitalya Ajyachi Rai |

Kazro tree, fish tailed palm |

|

Cudchirem |

Barazanachi Rai |

Ghoting (Terminallia Ballerica), Kazro, Kumyo, Huro, Kindal, Savar |

|

Latambarcem |

Sidhdachi Rai of Vadaval |

vad (Ficus Bengalensis), vonvol (mimusops elengi), |

|

Mencurem |

Barazan |

Saraca ashoka, Kosam (Schleichera oleasa) |

|

Sarvona |

Saterichi Rai |

Sarvar (Bombax Ceiba), Mangifera indica |

|

Sarvona |

Nirankaryachi Rai

of |

Alistonia Schloris |

|

Surla (Bicholim) |

Kontinchya Ajyachi Rai |

Ficus bengalensis, ficus religiosa, many evergreen trees, giant mango tree |

|

Surla (Bicholim) |

Purvatali Rai |

Randia spinosa, Gmelina arborea, Elephanto pusscaber, Smilexglabra |

|

Carambolim Brahma |

Ajobachi Tali |

Mystrica swamp forest, Semicarpus Catlekensis, Laginandra toxicaria, Dillenia pentagyna, machelus macarantha, Anthocephalus chinensis, Holigarna arnoliana |

|

Caranzol |

Holiyechi Rai |

Entada phaseoloides, ficus glometera, Terminilia crenuluta |

|

Compordem |

Devachi Rai |

Terminalia crenulata, Terminalia bellerica, Ficus Bengalensis, Caryota urens, Careya arborea, Macaranga peltata, Terminalia paniculata, Saraca indica, Lagerstroemia lanceolata parviflora, Acacia catechu, Alstonia scholarias, Dillenia pentagyna, Butea monosperma, Gmelina arborea, Holoptelia integrifolia, Pterocarpus marsupium, Xylia xylocarpa, Machilus Macramtha, Garcinia indica, Hopea wightiana, Holigarna arnotiano, Tetrameles nudiflora |

|

Derodem |

Dhoopachi Rai |

Canarium Strictum |

|

Malaoli |

Nirankaryachi Rai |

Mystrica swamp forest |

|

Mauzi |

Devachi Rai |

Cerbera odollam |

|

Morlem |

Ghotgachi Rai |

Terminallia Ballerica |

|

Pissurlem |

Mharinganachi Rai |

Ficus Racemosa, Ficus Hispida, Ficus Begalensis |

|

Pissurlem |

Pezali Devichi Rai |

paddy cultivation, |

|

Querim |

Maulichi Rai Of Vagheri |

wild turmeric |

|

Querim |

Ajobachi Rai |

giant trees, creepers and shrub |

|

Surla (Sattari) |

Devachi Rai |

Karvi shrubs, (blossom after seven years), endangered species of mushrooms |

|

Verlem |

Bhui Pann |

Mangifera indica (waghrukh, pakshi, jarmal) |

|

Poinguinim |

Partagal |

Ficus Benghalensis (largest banyan tree of Canacona) |

|

Gaodongarim |

Nasa Pann, Saturlichi Paikapann |

rare botanical gems and high floral diversity |

|

Dongurli |

Mundalgiro And Kolgiro of Thane |

Jambhul tree, Satvin, jackfruit, kumyo, salai, kusko |

|

Nagve (Sattari) |

Nagvechi Rai |

Terminalia elliptica, Terminalia paniculata, Terminalia Bellirica, Plumeria rubra |

|

Perne |

Mharinganachi Rai |

Strychnos nux Vomica, Careya arborea, Syzygium cumini |

Plant species of Sacred Groves

Surla, located in Bicholim taluk of north Goa is, still has the system of SG where villagers follow all the rules and norms associated with the grove. The Surla village consists of five SGs, namely Kontinchya Ajyachi Rai, Purvatali rai, Narayan Temple Rai, Malikarjun rai, Maldandeshwar Rai, of which Purvatali rai is the largest with the status of biodiversity heritage site and consists of medicinal plants such as Randia spinosa (Gelphal), Gmelina arborea (Shivan), Elephanto pusscaber (Elephant Foot), Smilexglabra (Gulvel), Carissa congesta (Karvanda), Amorphophallus compalcinatus (Suran), Vitis indica (Jungli-Draksha), Caryota urens (Bhillmad), Zanthoxylum rhetsa (Tirphal), Cyclea peltate (Padvel), Tinospora malabaricum (Amrtivel), Menispermacese, Mussaenda belilla (Shervad, Strychnosnux-vomica (Karo), Embeliavrobusta (Vavding), Pandanus Odorifer (Kewda), Holagarna integrifolia (Ran bivo), Argyreia sp. (Briddhadaruk Bhed), Hydnocarpus Laurifolia (Khast), Careya arborea (Kumbiyo), Spondia spinnata (Ambado), Gymnema sylvestre (Gudmar), Leea indica (Jino), Bridelia scandens (Ran patharphod), Tabernaemontana alternifolia (Nagulkudo), Terminalia tomentosa (Matti), Sterculia balanghas (Vadam), Lanneacoro mandelica (Moi), Ichnocarpus frutescens (Dudhshiri), Cryptolepis buchanani (Jambupatras ariva), Naregami aalata (Tinpan), Clerodendruminfortunatum (Bhandir), Sterculi aurens (Goan Arjuna), Gloriosa superba (Vaghati), Holoptelea integrifolia (Chireavilwa), Pueraria tuberosa (Bhooyi kohlaa), Dioscorea bulbifera (Karando), Dioscorea alata (Karandobhed), Euphorbia neriifolia (Nivdung), Artocarpus hirsutus (Pat phanas), Artocarpus integrifolia (Phanas), Holarrhena antidysenterica (Kudo), Grewia indica (Phalsa), Achyranthes aspera (Aghado), Capparis zeylanica (Govind Plal), Celastrus paniculatus (Kanguni), Diploclisia glaucescens (Vatanbel), Curcuma pseudomontana (Ran Halad), Wattakaka volubilis (Jivantibhed), Anamirta cocculus (Kakmar), Memecylon edule (Anjan), other species present in this grove are Haldina/ Adina cordifolia (Hed), Macaranga peltate (Chandado), Carallia brachiate (Panashi), Careya arborea (Kumyo), Dillenia indica (Karmal), Zanthoxylum rhetsa (Triphala), Artocarpus heterophyllus (Panas), Mangifera indica (Aam), Sterculia guttata (Bhekro), Sapium insigne (Huro), Grewia tiliifolia (Dhaman), Strychnos nux-vomica (Kajro), Annona reticulata (Ramphal), Dalbergia sp. (Gurakhya), Anacardium occidentale (Cashew), Ficus arnottiana (Phatarphad), Muntingia calabura (Singapore Cherry), Spondia spinnata (Ambado), Holoptelea integrifolia (Vavlo), Terminalia tomentosa (Madat), Litsea glutinosa (Miryo), Garcinia indica (Bhinda), Anacardiea sp. (Cockra), Hednocarpus wightian (Chalmogra), Mimusops elengi (Oval), Macaranga gigantea (Amti), Acacia catechu (Kath), Artocarpus sp. (Path Panas), Terminalia bellerica (Ghoting), Cassia fistula (Bayo), herbs and vines include Amorphophallus commutatus (Ransuran), Elephantopus scaber (Hastipadi), Mussaenda belilla (Shervad), Aerides maculosa (Draupadichi Veni), Smilax china (Chopchini), Aeginetia indica (Forest Ghost Flower), Carissa carandas (Kanna), Anamirta cocculus (Kakmarivel), Embelia ribes (Vavding), Sida acuta (Tapkadi), Sida cordifolia (Tapkadi), Vitis indica (Fox grapes), Smilax zeylanica (Gulvel), Clerodendrum infortunatum (White bharangi), Memecylon umbellatum (Anjan), Cyclea peltate (Padvel / patha), Tinospora cordifolia (Gudduchi/ Giloy) used for urinary and heart problems, Ixora coccinea (Pitkoli), Leea indica (Jino), Leucas aspera (Tumbo), Adhatoda vasica (Adulsa), Gloriosa superba (Vagacho Panjo), Hydnocarpus laurifolia (Khastvel), Curcuma pseudomontana (Ran halad), Mimosa pudica (Lajki), Dioscorea pentaphylla, Tabernaemontana alternifolia (Nagilkudo / Nagulkudo), Calycopteris floribunda (Uski), Smilex glabra (Gulvel), Murdannia spirata, Holarrhena antidysenterica (Kudo), Naregamia alata (Pithmadi), Helicteres isora (Kevan), Ricinus cuminis (Erand), Tylophora indica (Damavel), Jasminum malabaricum (Kusdi), Hemidesmus indicus (Dudhshiri), Cassia tora (Taikilo), Abrus precatorius (Gunji) used in urinary problems and cough.

Sacred grove Ajyachi Rai consists of an old Ficus Bengalensis, Ficus Religiosa, and many other evergreen trees. Villagers have maintained the customs related to SG, and this area is experiencing degradation due to mining iron ore.

Cudnem has SGs of Devachi Rai and Kumbharkhanitalya ajyachi rai consisting of Kazro tree (Cerbera odollam), Fish tailed palm. Latambarcem has SG of Sidhdachi Rai of Vadaval which consists of tree species such as Ficus Benghalensis (Vad), Mimusops Elengi (Vonvol).

Villagers of Mencurem (Bicholim) do not allow liquor inside the village because of the fear of presiding deity Mauli, and there is a tradition of obtaining permission of the deity by offering petals of Saraca Ashoka (a sacred tree of the grove) to the deity. SG of Barazan have various other species such as Schleichera oleasa (Kosam). Sarvona has sacred groves Saterichi Rai with Bombax Ceiba (Sarvar), Mangifera Indica (Mango), and Nirankaryachi Rai of Vathadev consists of Alistonia Schloris.

Compordem in Sattari has Devachi Rai with the preceding deity Brahamanimaya who is believed to protect the biodiversity of the forest, earlier SG had area of 37,620 sq. mts. but due to the construction of temple of Brahamanimaya, few lands had been cleared of the trees. The species present there include evergreen species of Ashoka, Terminalia crenulata (Matti), Terminalia bellerica (Ghoting), Ficus Bengalensis (Vad), Caryota urens (Bhillo mad), Careya arborea (Kumiyo), Macaranga peltata (Chandudo), Terminalia paniculata (Kindal), Saraca indica (Ashoka), Lagerstroemia parviflora (Nano), Acacia catechu (Khair), Alstonia scholarias (Santon), Dillenia pentagyna (Karmal), Butea monosperma (Palas), Gmelina arborea (Shivan), Holoptelia integrifolia (Vavalo), Pterocarpus marsupium (Assan), Xylia xylocarpa (Zamba), Machilus Macramtha (Elamb), Garcinia indica (Bhiran), Hopea wightiana (Pav), Holigarna arnotiano (Bibti), Tetrameles nudiflora (Shidam), creeper like Entada scandens (Garkani). The grove also has a perineal stream which was used to treat skin ailments in earlier times.

In Pernem SG of Mharinganachi rai where the preceding deity is Mhringan, who is an affiliate deity of Shri Ravalanath is of great importance to the villagers and consists of the trees of Strychnos nux Vomica (Kazaro), Careya arborea (Kumyo), Sygizuim cumini (Jambhul), and many other evergreen species of trees. Another village of Pernem Ibrampur consists of four sacred groves, Devachi Rai, Devachi Rai of Hankhane, Rashtrolyachi Rai of Tembwada Hankhane, Pirapeth of Angodwada among these Pirapeth of Angodwada is having rich species of Indian fishtail or sago plant (Caryoto urens) and several other evergreen tree species. Village Virnoda with SG of Nagardeshwar consists of trees such as Ficus Bengalensis, Garcinia Indica, Syzigium Cumini.

Carambolim Brahma a village in Sattari of Goa has a famous temple of Brahma and therefore village is also known as Brahma-Karmali. SG Ajobachi Tali with Ajoba is an inanimate deity and has a perennial spring which nurtures the several species such as Semicarpus Catlekensis (Biba), Laginandra toxicaria, Dillenia pentagyna, Machelus macarantha, Anthocephalus chinensis which is used in ayurvedic medicines, Holigarna arnoliana. Ecosystem of the region helps to maintain the availability of water all year round keeping the grove cooler than surrounding area. The grove shows that forest and water resources are dependent on each other for survival.

Caranzol, which is the largest village by the areal extent in Sattari and some part comes under Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary, has two SGs Karalyachi Rai and Holiyechi Rai situated far from the residential area of the village, has several taboos associated with them, which helps to protect the grove from the human intervention which leads to destruction. Villagers cut trees only during Shigmo festival after performing certain rituals. Holiyechi rai has an area of 27.42 ha. is home to species Garkani (Entada phaseoloides), rumad (ficus glometera), Madat (Terminilia crenuluta), Kino (Pterocarpus marsupium), Shiso (Dalbergia latifolia), Kindal (Terminalia paniculate), Matti (T. tomentosa), Jambhul (Sygizuim cumini) etc. Another village Derodem in Sattari, has a spectacular species of Dhup tree (Canarium strictum) in the Sacred grove of Dhoopachi rai named after the tree species that also follows the strict norm of not even taking a fallen leaf from the grove.

Malaoli (Sattari) village has a SG of Nirankaryachi rai, where the formless deity Nirankar is believed to protect the forest, and now villagers have built a small shrine outside the grove. Grove consists of vegetation with great ecological significance, including endangered species of Mystrica swamp spread over 0.25 ha. and other evergreen species. However, connectivity with metal road and agricultural activities has led to the shrinking of the grove area from 6 ha. and is protected by Goa Forest Department.

Nagve of Sattari, once uninhabited, has SG of Nagvechi rai having species of Matti, Kindal, Ghoting, Nano, Chafara. The villagers from nearby villages visit, during Narali Pournima to perform a thread ceremony and during the famous festival of Goa Shigmo, where villagers collect medicinal roots etc., from trees and prepare decoction from them. Another village of Mauzi have a SG of "Devachi Rai" which consists of Cerbera odollam (Kazro tree).

Morlem village named after the peacock, is situated on a height of 3,400 feet once used as natural fort in the bygone time. major deity worshipped in the village is Sateri Kelbai from which at short distance is the SG of Ghotgachi Rai which had large number of Ghoting (Terminallia Ballerica) once now compressed to a smaller area. Tree is believed to be the abode of the inanimate deity of Sacred grove Pishebai. Fruit of the tree is used to treat cough etc.

Pissurlem of Sattari is badly affected by the mining activities, had rich forest cover, the remains of which now are only seen in the SG of Pejalidevachi rai, which consists of 4-5 trees and Mharinganachi Rai spread in 2 ha. consists of species Ficus Racemosa, Ficus Hispida, Ficus Begalensis.

Querim of Sattari located in the Sahyadri mountains, is a treasure of biodiversity with a high number of SG, Ajobachi Rai is the largest SG, having area of 10 ha. and villagers are allowed entry only during the annual festival of Shigmo, Pishachi Rai, Maulichi Rai of Vagheri consisting wild turmeric species, Baldyachi Rai, and Comachi Rai. Deforestation activities in the village negatively impact these SGs, which consist of evergreen forests with giant tree species.

Surla of Sattari (like Caranzol) has its major area in Mhadei Wildlife Sanctuary was in isolation from modern way of life before the construction of Chorlaghat Belgaum road. With 60 percent of the total area under forest cover, the village consists of four SGs Devachi rai, Zunya Gaokadchi Rai (Junya Ganvatali rai), Pach Amyachi Rai, and among which in Devachi rai ant hill (termite mound) is worshipped which is devoted to goddess Sateri. These mounds have high ecological significance as they aid in rainwater percolation, increase soil nutrients, and resist erosion by mixing organic matter with the sand and soil. The hilly region with the green forest provides the most favourable climate for diverse flora and fauna. The species of Karvi shrubs (Carvia callosa), which blossom in seven years, Ipomoea sp., and endangered species of mushrooms are found in the SG. The grove is also blessed with many butterfly species such as Southern Birdwing, Common Rose, Tailed Jay, Lemon Pansy, Blue Tiger, etc.

Verlem of Sanguem taluk situated in Sahyadri mountains, is home to the tribe of Velip community who have, through generations, protected the groves of Bhui Pann and Jaita Pann of Salgini consisting of different varieties of Mangifera indica (waghrukh, pakshi, jarmal) which are left uncut as villagers believe these trees to be abode of deity. Although the main deity of village is Ramnath and Paik from which the SG is at a distance of 2 km where villagers from the neighbouring area also come to pay respect to the deity during religious functions, this is the only place in Goa having Saptlingeshwar.

Poinguinim, a village in Canacona has a hamlet called Partagal, which consists of the largest Banyan tree (Ficus Benghalensis) of Canacona, spread over in area of 2000-2500 sq. mts., providing natural habitat to avifauna species and various other species protected originally by the Velip community and worshipped by all the people in the area.

Dharbandora taluka in south Goa district consists of many SG, one of which is Khachkonchi Rai in Khachkon situated in Bhagwan Mahaveer wildlife sanctuary, which is protected from human exploitation. Rituals are not performed here, unlike at several other SG festivals. But the people of the surrounding area have the same kind of respect for the area as any other SG.

The most common tree species found in SG are of Matti (Terminalia elliptica) which is also a state tree of Goa, Terminalia paniculata (Kindal) used for diabetes and menstrual disorders, Terminalia chebula (Hirda) used to increase appetite and cure constipation, Terminalia bellerica (Goring), Dalbergia latifolia (Sissum), Saraca indica (Ashoka), Mimusops elengi (Onwal), Ficus bengalensis (Vad), Lagerstroemia lanceolata parviflora (Nano), Bridelia retusa (Katekawach), Adenanthera pavonia (Gunj), Acacia catechu (Khair) bark of this tree is used to control bleeding, Alstonia scholarias (Saton), Grewia tilliaefolia (Dhaman), Dillenia pentagyna (Karmal), Emblica officinalis (Awala), Caryota urens (Billemad), Palas (Butea monosperma) its flower, leaves and bark are used in swelling and menstural flow problems, Gmelina arborea (Shivan), Adina Cordifolia (Hedu), Holoptelia integrifolia (Vavalo), Pterocarpus mauriliana (Assan), Cassia fistula (Bayo), Artocarpus heterophylia (Phanas), Artocarpus hirsute (Pal panas), Artocarpus lakoocha (Otomb), Syzygium cumini (Jamun), Sterculia foetida (Nagin), Lannea grandis (Moi), Mytragyna parvifiora (Kalamb), Pongamia pinnata (Karanji), Careya arborea (Kumbiyo), Hollarhena antidysenteric (Kudo), Schleichera oleosa (Kusum), Macaranga peltata (Chandado), Mangifera indica (Ambo), Semicarpus anacarclium (Bibba), Ficus religiosa (Pipal), Thespecia lampa (Ran bhendi), Ficus asperrima (Kharvat), Bombax malabaricum (Sarwar), Tectona grandis (Sagvan), Xylia xylocarpa (Zamba), Machilus macrasmtha (Elamb), Buchanania lanzan (Char), Hydrocarpus laurifolia (Khasti), Holigarna arnootina (Bibbo), Calophyllum wightianum (Irai), Strychonos nux-vomica (Bhiran), Mystrica malabarica (Ranjaiphal), Hopea wightiariu (Pava), Sapindus emarginalis (Rite). The other Sacred plants and trees found here are Anthocephalus Cadamba (Kadamb), Terminalia Arjuna (Arjun), Prosopis Spicigera (Shami), Tamarindus Indica (Chinch), Areca Catechu (Palm of Supari), Ficus Racemosa (Audumbar), Zizyphus Mauritiana (Bori), Tetrameles Nudiflora (Shidam), Barringtonia Acutangula (Menkumyo), Santalum album (Chandan), Sterculia Urens (Dhavorukh), Leea Indica (Dino), Ficus microcarpa (Nandruk), Couropita guianensis (Shivling), Hydnocarpus laurifolia (Khashta), Strychnos Nux-vomica (Kazro), Sageraea laurifolia (Harkinjal), Musa paradisiaca (Kel), Curcuma longa (Halad), Tinospora cordifolia (Amrut-vel), Azadirachta indica (Neem), Mammea suriga (Surangi), Jasminum auriculatum (Jui), Nyctanthes arbor-tristis (Prajakta), Nelumbo nufifera (Kamal), Jasminum grandiflorum (Jaee), Jasminum sambac (Mogri), Ocimum sanctum (Tulshi), Michelia champaca (Sonchafa), Pandamus odoratissimus (Kevada), Tagetes erecta (Roza), Calotropis gigantea (Rui), Ixora Coccinea (Patkolni), Impatiens balsamina (Dev-chiddo), Lygodium Flexuosum (Ramachi bota), Trachelospermum jasminoides (Kunda), Bambusa vulgaris (Bamboo), Carypha umbraculifera (Buto), Vigna mungo (Udid), Vateria indica (Dhoop), Putranjiva roxburghii (Putranjiva), Ficus tsjahela (Kel), Crossandra infundibuliformis (Aaboli), Bauhinia racemosa (Apata), Garcinia indica (Bhirand), Antiaris toxicaria (Chandkudo).

The wild plants of SG are also used by the villagers for the decoration purposes which include Kangala(Celastrus paniculatus), Ghaghryo(Connarus memocarpus), Kanakicho kom(Dendrocalamus Strictus), Uski(Ge tonia floribunda), Harna(Senecio belgaumensis), Nagalkudo(Tabernae montuna alternifolia), Matti(Terminalia elliptica), Kavandal(Trichosanthes cucumerina), Shervad(Mussaenda glabrata), Parijat(Nyctanthes arbo-tristis), Ashoka(Saraca asoca), Ghotvel(Swilax ovlifolia), Fagla(Memordica dioica), Salkando(Adenia bondala), Patphanas(Artocarpus hirsutus), Kanna(Carissa spinarum), Makad bhirand(Garcinia gummigutta), Bhedas(Syzygium hemispherium), Rui(Calotropis gigantea), Rumad(Ficus racemose) bark, roots and leaves of this plant are used to treat stomach vermicide, Vagh chapko(Glorisa superba), Bharangi(Clerodendrum serratum), Dino(Leea macrophylla), Khayati(Corchorus olitorius), Ranmethi(Melilotus indica), Navali(Merremia vitifolia), Aakur(Acrosticum aurous), Pendhare(Tamilnadu uliginosa), Chivar(Oxytenanthora ritcheyi), Ran karmol(Dillenia indica), Kudduk(Celosia argentes), Bonkalo(Cheilocostus speciosus), Taikalo(Cassia tora), Dhavarukh(Sterculia urnes), Asale(Grewia nervosa), Ran-karano (Dioscorea bulbifera), Kevan(Helicteres isora), Zirmulo(vigna vexillate), Tamhan(Lagerstroemia speciosa), Teeli(Sesamum indicum), Tirphala(Zanthoxylum rhesta), Nano(Logerstroemia macrocarpa), Bonaki(Pandamus tectorium), Bel(Aegle marmelos) its fruit is udes for stomach related problems and cough and cold, Bhillo mad(Caryoto urens), Bhekare(Stercullia balanghas), Rambhene(Abelmoschus Manihot) parths such as fruits, leaves, flowers, twig, bark, shoots, bulbils etc. are used by the villagers during rituals and festivals for decoration.

Host plants of butterfly which are found in SG are Tikki(Cinnamomun) is a host plant to Blue bottle, Common jiy, Tailed jay, Common mirne, Imperial, Karpil(Murraya marmelos) is host to Lime butterfly, Common Mormon, Paris peacock, Raven, Red halen, and blue mormon, Bel(Aegle marmelos) is host plant to Common Mormon, Triphal(Zenthoxylam budrunga) is host to Malabar banded peacock and Common Mormon, Taikalo(Cassa tora) is host to Common emigrant, Mottled emigrant, Common grass yellow, Lazalu(Mimosa pudica) is host to Common grass yellow, Zebra blue, Shrimandoli(Adenia hondala) is host to Tawny coster, Tamil lacelving, Clipper, Chafra(Elacortia montana) is host to Rustic and Common leopard, Dhaman(Grewia tiliaefolia), Narkya(Nothapodytes nimoniana) are both host to Common sailor, Jambo(Xylia xylocarpa) is host to Common sailor, Hedge blue, Common cerulean, Sharwad(Mussaenda) and Kalam(Mitragyana parviflora) both are host to Commander, Gulvel(Tinospara cardifolia) is host to Clipper, Kumyo(Careya arborea) is host to Grey count, Khazkuli(Tragia Involucrata) is host to Angled castor, Common castor, Rui(Calotropis gingantia) is host to Blue tiger, Plain tiger, Rumad(Ficus glamorata) is host to Common crew and Common map, Kalezad(Diospyros candallana) is host to Malbar tree nymph, Red spot duke, Shiras(Albezia spp) is host to Zebra blue, Kusum (Sliecheria oleosa) is host to Hedge blue), Palas(Rutea menosperma) is host to Grass blue, Pea blue, Khulkhulo (Cratolaria spp) is host to Common cerulean and Pea blue, Gunj (Abrus pracatorius) and Karanj (Pangamia pinata) is host to Common cerulean hence SG plays an important role in species diversity of various flora and fauna. Table 2 lists taluk and district wise plant species of Goa.

Table 2 Taluk wise plant species of Goa.

|

District |

|

North Goa |

South Goa |

||||

|

Taluk |

|

Pernem |

Bicholim |

Sattari |

Sanguem |

Quepem |

Canacona |

|

Tree species- Scientific name |

common name |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Abrus precatorius |

Gunji |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Acacia catechu |

Kath, Khair |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

Adansonia degitata |

Gorakh Chinch |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

Adenanthera pavonia |

Gunj |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Adhatoda vasica |

Adulsa |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

Adina Cordifolia |

Hedu |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Aegle marmelos |

Bel |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Alstonia scholarias |

Saton |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Anacardiea sp. |

Cockra |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Anacardium occidentale |

Cashew |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Anamirta cocculus |

Kakmari-vel |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Annona reticulata |

Ramphal |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Anthocephalus Cadamba |

Kadamb |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Antiaris toxicaria |

Chandku-do |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

Artocarpus heterophyllus |

Panas |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Artocarpus hirsute |

Pal panas |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Artocarpus sp. |

Path Panas |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Azadirachta indica |

Neem |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Bambusa arundinacea |

Velu |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Barringtonia Acutangula |

Menkumyo |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Bauhinia racemosa |

Apata |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Bombax malabaricum |

Sarwar |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

Bridelia retusa |

Katekawach |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Butea monosperma |

Palas |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Carallia brachiate |

Panashi |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Careya arborea |

Kumbiyo, Kumyo |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Carissa carandas |

Kanna |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Caryota urens |

Billemad |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Cassia fistula |

Bayo |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Clerodendrum infortunatum |

White bharangi |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

Dalbergia latifolia |

Sissum |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Dillenia indica |

Karmal |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Dillenia pentagyna |

Karmal |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Embelia ribes |

Vavding |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Emblica officinalis |

Awala |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Ficus arnottiana |

Phatarphad |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Ficus asperrima |

Kharvat |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Ficus bengalensis |

Vad |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Ficus microcarpa |

Nandruk |

|

|

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Ficus Racemosa |

Audumbar |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Ficus religiosa |

Pipal |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Ficus tsjahela |

Kel |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Garcinia gummigutta |

Makad bhirand |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Garcinia indica |

Bhirand |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Gloriosa superba |

Vagacho Panjo |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Gmelina arborea |

Shivan |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Grewia tilliaefolia |

Dhaman |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Haldina/ Adina cordifolia |

Hed |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Hednocarpus wightian |

Chalmogra |

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

Helicteres isora |

Kevan |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Hemidesmus indicus |

Dudhshiri |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Holarrhena antidysenterica |

Kudo |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Holigarna arnootina |

Bibbo |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Holoptelea integrifolia |

Vavlo |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Hopea wightiariu |

Pava |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Hydnocarpus laurifolia |

Khashta |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Impatiens balsamina |

Dev-chiddo |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

Ixora Coccinea |

Patkolni |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Jasminum malabaricum |

Kusdi |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Lagerstroemia lanceolata |

Nano |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Lannea grandis |

Moi |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Leea Indica |

Dino |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Litsea glutinosa |

Miryo |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Macaranga gigantea |

Amti |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Macaranga peltata |

Chandado |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Machilus macrasmtha |

Elamb |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Mammea suriga |

Surangi |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Mangifera indica |

Ambo |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Memecylon umbellatum |

Anjan |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Michelia champaca |

Sonchafa |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Mimosa pudica |

Lajki |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Mimusops elengi |

Onwal |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Muntingia calabura |

Singapore Cherry |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

|

Mussaenda belilla |

Shervad |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Mystrica malabarica |

Ranjaiphal |

|

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Mytragyna parvifiora |

Kalamb |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Naregamia alata |

Pithmadi |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Nyctanthes arbor-tristis |

Prajakta |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

|

Pandamus odoratissimus |

Kevada |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Pongamia pinnata |

Karanji |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Pterocarpus mauriliana |

Assan |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Putranjiva roxburghii |

Putranjiva |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Randia spinosa |

Gelphal |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Sageraea laurifolia |

Harkinjal |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Santalum album |

Chandan |

|

|

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Sapindus emarginalis |

Rite |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

Sapium insigne |

Huro |

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

|

Saraca indica |

Ashoka |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Schleichera oleosa |

Kusum |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Smilax zeylanica |

Gulvel |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Spondia spinnata |

Ambado |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

|

Sterculia guttata |

Bhekro |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Sterculia Urens |

Dhavorukh |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Strychnos nux-vomica |

Kajro, Bhiran |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

Syzygium caryophyllatum |

Bhedas |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Syzygium cumini |

Jamun |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Syzygium travancoricum |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Tabernaemontana alternifolia |

Nagilkudo / Nagulkudo |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

|

Terminalia Arjuna |

Arjun |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Terminalia bellerica |

Goring, Ghoting |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Terminalia chebula |

Hirda |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Terminalia crenulata |

Madat |

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Terminalia elliptica |

Matti |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Terminalia paniculata |

Kindal |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Tetrameles Nudiflora |

Shidam |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

✓ |

|

Vateria indica |

Dhoop |

✓ |

|

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

|

Xylia xylocarpa |

Zamba |

|

|

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Zanthoxylum rhetsa |

Triphala |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Zizyphus Mauritiana |

Bori |

✓ |

|

|

✓ |

|

✓ |

Tree species (listed in Table 2) have various cultural practices associated with them among villagers like Pissurle having SG of Pejali-devichi rai who is believed to reside in the village and bless rice crops of the area. In Verle villagers do not take anything from the SG Bhuipann, except for the month of Bhadrapad when herbs, roots, shoots, and leaves having medicinal properties are collected and distributed among all. After this, Koduvaparab is celebrated by drinking a decoction in the early morning, which is believed to keep diseases away. Through cultural practices, these tree species have been preserved for ages.

SG, having rich biodiversity, provides ecosystem services like provisioning services, cultural services, and regulating services such as carbon sequestration and hydrological balance maintenance. Sacred Grove Ecosystem Services (SGESA), an all-India research project by the Ministry of Environment and Forest, has tried to access the ecosystem value of SG all over India (Kerkar, 2008). First and foremost, groves maintain a clean environment, water and soil, which are the basic need of every living being on earth. The unique biodiversity of SG, which is protected for ages harbouring several endangered and endemic flora and fauna provides gene bank for the same. The dense and diverse vegetation of groves allows greater water infiltration capacity in the area, as a result, perennial springs have their origin in Sacred groves, making them a source of freshwater supply in the area throughout the year for the local people as well as other living beings. Also, nutrient cycling is greater in SG because of the presence of biodiverse plant species, which also helps increase the productivity of crops in the neighbouring area as nutrients get transported through springs in the fields. Species such as bees, beetles, trips, midges, and birds are common in SG and help in pollination, providing essential ecosystem service for out crossing and sexual reproduction of plants, which also improves field crops. Ecologically valuable species, which conserve high amount of nitrogen, phosphorous, magnesium and calcium in their leaves, are found in several sacred groves.

The temperature in sacred groves is lower than in surrounding areas, providing an ideal atmosphere for species to grow and flourish. Natural resources like woody species of trees in SG are great stores of carbon. They serve essential goods for human needs, such as food, potable water, medicine, and fibre. Also, many threatened species remain protected in SG, such as Mystrica swamp of Nirankarachi Rai and Ajobachi tali of Brahma karmali in Sattari. Along with these, regulating services such as sequestration of carbon and hydrological balance of the area is also maintained, as SG consists of old woody trees that have carbon stock and perennial springs also originate from many SG such as Nirankarachi Rai of Maloli. Groundwater recharging is also a natural phenomenon in biodiversity-rich region. With this SG are the ideal spot for biodiversity conservation where many rare and endemic flora and fauna are found.

Cultural services are of the utmost importance among villagers, as it is believed that their ancestor’s spirit and deity to live in these groves hence, and all rituals and festivities of villagers are associated with these groves and people are emotionally attached with this system. This emotional attachment makes it easier to maintain discipline in following rules associated with the grove. The system is evident of how traditional values have stronger roots and can be used to maintain the natural surroundings by preserving the ecosystem services. Every village has tradition of giving offerings to the guardian spirit of the village. Each has different stories associated and a particular month in which ritual occurs. Here, all the villagers, irrespective of the religion and caste do the rituals.

The groves provide a traditional healthcare system as they are home to several medicinal plant and tree species, many of which are rare today and in need of protection. Some of the SG have been badly affected by mining, which is done in the absence of environmental norms and regulations, in the area such as in Mulgao of Bicholim, iron ore excavation has led to the degradation of fertile land and is having a negative impact on the biodiversity of the area. Many SGs which once had rich floral and faunal biodiversity now are restricted to only few trees left for the religious purposes. Mapusa of Bardez had SG of Bodgeshwar and Kanakeshwar, which once had bamboo groves and several other species but is now in a degraded state.

Conclusion

Sacred groves have been providing ecological benefits through the conservation of biodiversity with rich natural resources. Rich tree cover in the SG allows water to percolate in the ground, which helps maintain the hydrological balance of the region. This provides sources of perineal water streams to the nearby villages and prevents the soil from getting eroded. Old trees and plants of groves have high amount of carbon storage. Instead of several benefits of SG, it is looked up only for cultural perspective by the authorities with poor management resulting in the degradation. Rising activity of unplanned development around SG, plantation of invasive species, unregulated land use and land cover change, and growing human population have escalated demand for natural resources. The changing pattern of cultural beliefs among the younger generation has threatened such ecologically rich areas.

SGs are important for cultural purposes and biodiversity conservation, medicinal plant species, and water security because they are rich in vegetation. The loss in the area of SG is leading to the deterioration in the biodiversity of the area, with species that are in the state of being endangered or extinct. Therefore, it is necessary to conserve such forest patches. The temple worship is leading to the cutting of trees in groves and the construction of temples (Chandran et al. 1998) without realising the ecosystem values provided by the biodiversity of SG. Many species of plants are exclusive to a few SG only (Rajasri et al. 2014) and, therefore, urgently need to be conserved and replanted with the help of saplings. Since, sacred groves are under threat from anthropogenic activities, therefore the proper guidelines for visiting such biodiversity-rich area should be made and strictly followed by the visitors then only groves can be conserved and people living there can reap their benefits both economically and culturally. Also, SG which comes under reserved forest or are protected by the forest department, are well protected even in non-cultural scenarios. The protection is not affected by the cultural beliefs of the people. Also, before formulating any policies, cultural beliefs need to be understood and valued because these beliefs have played a major role in conserving these forests.

References

-

Mushtaq A., Manjul D., 2023,

Nucleus model of sacred groves

(sacred groves: the nuclei of

biodiversity cells) traditional

beliefs, myths, associated

anthropogenic threats and

possible measures of

conservation in Western most

regions of lesser Himalayas,

India, Acta

Ecologica Sinica

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chnaes.2023.05.002

-

Ray R., Chandran, M.D.S.,

Ramachandra T.V., (2014),

Biodiversity and ecological

assessments of Indian sacred

groves. Journal of Forestry

Research 25, 21–28.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0429-2

-

Ramachandra, T.V., Setturu, B.,

Rajan, K.S. Chandran, M.D.S.

(2017), Modelling the forest

transition in Central Western

Ghats, India. Spat. Inf. Res.

25, 117–130.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41324-017-0084-8

-

Gadgil, M., Vartak, V.D. (1976),

The sacred groves of Western

Ghats in India. Econ Bot 30,

152–160.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862961

-

Ormsby, A.A. (2011), The Impacts

of Global and National Policy on

the Management and Conservation

of Sacred Groves of India. Hum

Ecol 39, 783–793.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-011-9441-8

-

Patwardhan, A., Ghate, P.,

Mhaskar, M. Bansude, A. (2021),

Cultural dimensions of sacred

forests in the Western Ghats

Biodiversity Hot Spot, Southern

India and its implications for

biodiversity protection. Int. j.

anthropol. ethnol. 5, 12.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s41257-021-00053-6

-

Sayantani Chanda, Ramchandra T.

V., (2019), Sacred Groves

– Repository of Medicinal

Plant Resources: A review,

research and reviews: Journal of

ecological sciences.

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/Sacred%20Groves/results.html

-

Sayantani Chanda, Ramchandra

T.V., (2019), Vegetation in the

Sacred Groves across India: A

Review, Research and Reviews:

Journal of Ecology

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/Vegetation/index.htm

-

Sumesh N. D., M.K. Mahesh, M.D.

Shubhash, Ramchandra T.V.,

(2013), Fern diversity in Sacred

Forest of Yana, Uttara Kannada

Central western ghats,

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/Yana/references.html

-

Murugan, K., Ramachandran, V.

S., Swarupanandan, K., &

Remesh, M. (2008).

Socio-cultural perspectives to

the sacred groves and serpentine

worship in Palakkad district,

Kerala.

https://nopr.niscpr.res.in/handle/123456789/1712

-

Alex, R.K. (2022). Kaavu in

Kerala (Sacred Groves in

Kerala). In: Long, J.D., Sherma,

R.D., Jain, P., Khanna, M. (eds)

Hinduism and Tribal Religions.

Encyclopedia of Indian

Religions. Springer, Dordrecht.

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1188-1_834

-

Rajasri Ray, M.D. Subash

Chandran and T.V. Ramachandra,

(2011), Sacred groves in

Siddapur Taluk, Uttara Kannada,

Karnataka: Threats and

Management Aspects, Centre for

Ecological Sciences, Indian

Institute of Science,

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/ETR38/index.htm

-

Rajasri Ray and Ramachandra

T.V., 2010. Small sacred groves

in local landscape: are they

really worthy for conservation?

Current Science, Vol. 98, No.9,

10 May 2010,

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/small_sacred_groves/index.htm

-

Sharma, S., Kumar, R. (2021),

Sacred groves of India:

repositories of a rich heritage

and tools for biodiversity

conservation. J. For. Res. 32,

899–916.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-020-01183-x

-

B., Rajesh, (2016), Sacred

Groves: Floristic Diversity and

their Role in

Conservation of Nature,

Forest Research, 5, 161.

https://10.4172/2168-9776.1000161

-

Kale, M.P., Chavan, M.,

Pardeshi, S. Josi, C. Verma,

A.P. Roy, P.S. Srivastav, S.K.

Srivastava, V.K. Jha, A.K.

Chaudhari, S. Giri, Y. Krishna

Murthy Y.V.N. (2016) Land-use

and land-cover change in Western

Ghats of India. Environ Monit

Assess 188, 387

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-016-5369-1

-

M.L. Khan, Ashalata

Devi, Khumbongmayum, R.S.

Tripathi, 2008, The Sacred

Groves and their Significance in

Conserving Biodiversity an

Overview, International Journal

of Ecology and Environmental

Sciences 34 (3): 277-291

https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/31232826/Sacred_Groves_Review-libre.PDF

-

Bhagwat SA, Rutte C. 2006.

Sacred groves: potential for

biodiversity management. Front

Ecol Environ. 4(10):

519–524.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/250077824_Sacred_groves_Potential_for_biodiversity_management

-

Malgorzata Blicharska, et. al.

(2013) Safeguarding biodiversity

and ecosystem services of sacred

groves – experiences

from northern Western Ghats,

International Journal of

Biodiversity

Science, Ecosystem Services

& Management, 9:4,

339-346

https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2013.835350

-

Arpita Vipat and Erach Bharucha,

2014, Sacred Groves: The

Consequence of Traditional

Management, Journal of

Anthropology, Article ID 595314,

8 pages

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/595314

-

Gadgil and Vartak, Sacred groves

of Maharashtra an Inventory

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/mg/pdfs/mg038.pdf

-

Ripu M. Kunwar et. al. 2020,

Change in forest and vegetation

cover influencing distribution

and uses of plants in the

Kailash Sacred Landscape, Nepal,

Environment, Development and

Sustainability,

22:1397–1412

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0254-4

-

Wendy J. & Alison Ormsby,

(2017) Urban sacred natural

sites – a call for

research, Urban Ecosystem

20:675–681

https://10.1007/s11252-016-0623-4

-

Ogundiran, A.

(2020) Managing Epidemics

in Ancestral

Yorùbá

Towns and Cities:

“Sacred Groves” as

Isolation Sites,

Afr Archaeol Rev

37:497–502

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-020-09407-5

-

Kit Wah Kit Lee et. al., Can

Disparate Shared Social Values

Benefit the Conservation of

Biodiversity in Hong

Kong’s Sacred

Groves? Human Ecology

2023

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-023-00443-8

-

David Hecht,

GIS, Sacred Sites, and Remote

Sensing of Sacred Landscapes,

Books & Reports

-

T.V. Ramachandra, M.D. Subash

Chandran, Ananth Ashisar, G.R.

Rao, Bharath Settur, Bharath H.

Aithal, 2012, Tragedy of the Kan

sacred forests of Shimoga

district: need for urgent policy

interventions for conservation

CES, Energy & Wetlands

Research Group, CES, IISc

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/ces_tr/TR128/section2.htm

-

T.V. Ramachandra, Subash

Chandran M.D Joshi N.V., Sooraj

N P Rao G R Vishnu Mukri, 2012,

Ecology of sacred Kan forests in

central Western Ghats, Centre

for Ecological Sciences, Indian

Institute of Science,

Bangalore

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/ETR/ETR41/materials.htm#:~:text=3.1)%2C%20forms%20the%20northern%20end,species%20(Devar%2C%202008)

-

T.V. Ramachandra, Vinay S,

Vishnu D. Mukri, M.D. Subash

Chandran, 2017, Irrational

allotment of common lands - Kan

sacred forests in Sagar Taluk,

Shimoga district, Karnataka for

non-forestry activities, Energy

& Wetlands Research Group

Centre for Ecological Sciences,

CES, IISc.

https://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/ETR135/ETR135.pdf

-

Biodiversity Conservation, Land

Use, Land Use Change and

Forestry (LULUCF) Programmes

Ideas for Implementation, 2008,

UNDP India

https://www.undp.org/india/publications/newsletter-biodiversity-conservation-through-community-based-natural-resource-management

-

Government of India – UNDP

Partnership on Biodiversity

Conservation, 2012, UNDP

India

https://www.undp.org/india/publications/government-india-%E2%80%93-undp-partnership-biodiversity-conservation

-

Sacred Natural Sites Guidelines

for Protected Area Managers,

2008, IUCN

https://csvpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/PAG-016.pdf

Other links

-

Directorate of Agriculture,

Goa

https://www.agri.goa.gov.in/Overview;jsessionid=79447A37E13712BC82DAF659656B0897

-

Forest department, Government of

Goa

https://forest.goa.gov.in/forest-types

-

Forest department, Government of

Goa

medicinalplants.pdf (goa.gov.in)

-

Report of “Purvatali

Rai” sacred grove

for declaring

as biodiversity heritage

site (BHS)

https://gsbb.goa.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Report-on-Purvatali-rai-Sacred-Grove.pdf

-

C.P.R. Environmental Education

Centre (CPREEC)

https://cpreec.org/organization/

-

Department of Information and

Publicity

https://dip.goa.gov.in/physiography/

Spatial Distribution of Sacred Groves in Goa state, India

T V Ramachandra, and Prasanna B

M

IISc-EIACP, Environmental

Information System, CES TE-15

Indian Institute of Science,

Bangalore 560012

E Mail:

tvr@iisc.ac.in, envis.ces@iisc.ac.in, Tel:

91-080-22933099/

23608661

Introduction

Sacred water bodies, Sacred animals, Sacred trees and Sacred groves are India’s ancient tradition of conserving nature by giving it a spiritual dimension. India has the culture of considering every forms of life as well as abiotic creations as a divine and these are associated with variety of primitive cults. Sacred groves are extended part India’s unique heritage system of natural resource management and preservation, also good examples of indigenous practice of forest conservation on the name of local deity. These are climax vegetation pockets are located in remote tribal areas along the Western Ghats in India (Vartak and Gadgil,1981). These forest patches are true indicators of the type of vegetation that once existed along these hilly terrains, long before the dawn of modern civilization. Removal of any plant material, even of dead wood, litter collection, grazing and hunting in the grove is taboo (Vartak and Gadgil,1981,1981a). The belief of linkages of forests with water availability, coupled with taboos, and rituals supported by mystic folklore, have been the motivating conservation of the sacred groves. Ritual activities are carried out in the sacred grove as part of annual festivals (https://cpreec.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Restoration-of-Sacred-Groves-of-India.pdf).

Sacred groves occur in many parts of India viz., Western Ghats, Central India, northeast India, etc. particularly where the indigenous communities live. Sacred groves vary in size from < 1 to > 100 ha, depending on their location and management profile. Sacred groves are alknown as kans, Devarakadu, Bana, Jetti (in Karnataka), and Kavus (in Kerala). Occurrence of Sacred groves varies in a wide range of situations, from estuaries of west coast to the montane heights of the western Ghats at over 2000m elevation. It covers the ecosystem from mangroves and freshwater swamps to different forest type (M.D.S. Chandran et al. 1997).

In Goa, sacred groves are known by various names such as Devrai, Devran or Pann. The best preserved sacred groves of Goa are situated in Keri village of Sattari. Durgah and Rashtroli are the deities to which the sacred groves are dedicated in Goa. Some of the species commonly found in the sacred groves are Ceylon oak, red silk cotton tree and pipal tree. The tribals of Goa Gavda, Kunbi, Velip and Dhangar-gouli worship various forms of nature. They have a tradition of sacred cow, sacred goat, sacred banyan tree, sacred hill, sacred stone, sacred ponds and also sacred groves (Amirthalingam, M., 2016).

Role of Sacred grove in conservation of Biodiversity

Several valuable food plants including mango (Mangifera indica), jackfruit (Artocarpus integrifolia), Garcinia spp., Caryotaurens, an important starch and toddy producing palm, spices like pepper (Piper nigrum) and cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.), etc. are protected in the sacred forest although it is situated near or in-between the agriculture fields, close to the human settlement. Fresh water swamps called Myristica swamp which can be seen in a few locations of Wester Ghats harbor several endemic and rare trees species such as wild nutmeg, Myristica fatua var. magnifica, and Gymnacrantheracanarica are survived as a part of Sacred grove in Kathlekan, Uttara Kannada. Sacred groves shelter many elements of the endemic biota in the local landscape (M.D.S. Chandran et al. 1997). Several medicinal plants and animals that are threatened in the forest are still well conserved in the sacred groves. This necessitates inventorying, mapping and monitoring of ecologically fragile sacred groves. It is crucial to formulate well thought out plan of the conservation of our plant wealth before it is too late (Vartak and Gadgil,1981a).

Importance of sacred groves (Rajasri Ray, et al. 2011) are

- provide shelter to numerous species of plants and animals.

- Provide cultural services as believed to have great powers to heal body and spirit.

- reservoirs of biodiversity.

- the last refuse for endemic and endangered species of plants and animals.

- the storehouses of medicinal plants valuable to village communities as well as modern pharmacopoeia.

- contain relatives of crop species that can help improve cultivated varieties.

- help in maintaining the water cycle and water table in local areas.

- helps to improve soil stability, prevent top soil erosion and provide irrigation for agriculture during lean seasons.

Threats to the sacred groves