| Sahyadri Conservation Series: 13 |

ENVIS Technical Report: 39, March 2012 |

|

EXPLORING BIODIVERSITY AND ECOLOGY OF CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS |

|

Energy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560012, India.

*Corresponding author: cestvr@ces.iisc.ac.in

|

|

TERRESTRIAL ECOSYSTEM

BIODIVERSITY

The Biodiversity or the Biological diversity refers to the different genera and species of organisms present in an area. The degree of species diversity varies from one ecosystem to the other. India is a very rich country in terms of the rich flora and fauna present in the natural ecosystems. The presence of different kinds of forests, variability in climatic conditions, rainfall and topography are main reasons for presence of such vast biodiversity in this country. However, due to various reasons such as climate change, increasing urbanization, industrialization, encroachment, etc. the Biodiversity is facing a major threat in many parts of the world. So, to raise public awareness in this regard and enhance the participation of people in saving the biodiversity, the United Nations General Assembly has declared the year 2010 as ‘International Year of Biodiversity’. This declaration is aimed at carrying out various activities to increase awareness and to involve people, organizations and Governments from all backgrounds for conservation of biodiversity. The Western Ghats of the Indian peninsula constitute one of the 34 global biodiversity hotspots along with Sri Lanka, on account of exceptional levels of plant endemism and by serious levels of habitat loss (Conservation International, 2005). As per the criteria for delineating an ecosystem as ‘Biodiversity Hotspot’ set by Conservation International, a region must contain at least 1500 species of vascular plants as endemics and it has to have lost at least 70 percent of its original habitat. This hotspot contains unique flora and fauna with high levels of endemism (Table 1) along with harboring endemic and RET species of fauna such as Asian elephants, tigers, lion tailed macaques, nilgiri langurs, etc. However, the high population pressure in both the countries of this hotspot has seriously stressed the region’s biodiversity.

Table 1: Biodiversity of the Western Ghats with % endemism

| Group |

Total |

Endemic Species |

% Endemism |

| Angiosperm |

4000 |

1500 |

38 |

| Butterflies |

330 |

37 |

11 |

| Fishes |

289 |

118 |

41 |

| Amphibians |

135 |

101 |

75 |

| Reptiles |

156 |

97 |

62 |

| Birds |

508 |

19 |

4 |

| Mammals |

120 |

14 |

12 |

The flora of Western Ghats comprises about 12,000 species ranging from unicellular cyanobacteria to angiosperms. In this spectrum the flowering plants constitutes about 27% of Indian flora with 4000 species of which about 1,500 species are endemic. Most of the endemic plants of peninsular India are paleoendemics having found favourable ecological niches in the hill ranges on either side of the Western and Eastern ghats. The ecological niches in Western Ghats resemble islands so far as the distribution of endemic species is concerned (Nayar, 1996). Many of these species are traditional source of medicines. Majority of the medicinal plants in India are higher flowering plants with trees 33 %, shrubs 20 %, herbs 32 %, climber 12 % and others 3 %. They also play a significant role in the economy of the country, providing raw materials for a variety of industries. Depletion of biodiversity at an alarming rate due to anthropogenic activities has necessitated inventorying, monitoring and management. Hence, vegetation and floristic studies have gained increasing importance and relevance in recent years.

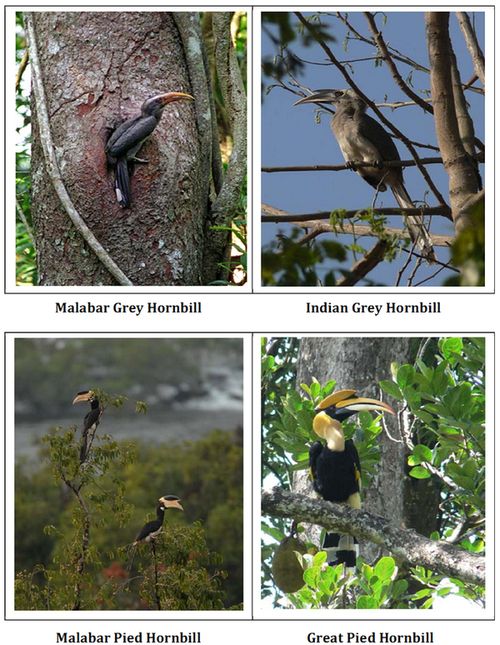

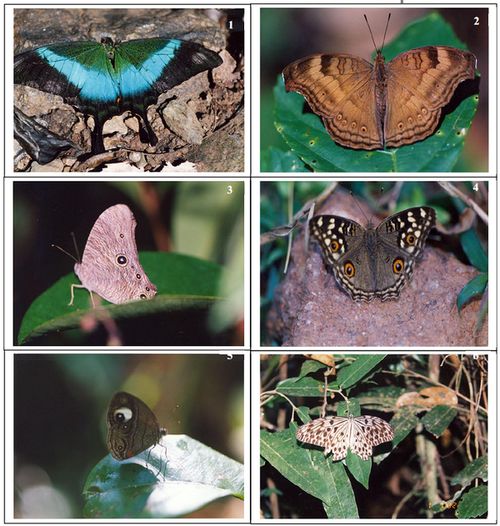

The Western Ghats are also rich in faunal diversity and endemism (Daniels 2003; Sreekantha et al. 2007) accounting for 330 butterflies (11% endemics), 289 fishes (41% endemics), 157 amphibians (85% endemics), 156 reptiles (62% endemics), 508 birds (4% endemics) and 120 mammals (12% endemics).The central Western Ghats is also a rich repository of faunal diversity. They harbor many rare, endangered and endemic faunal species whose presence signifies the ecological importance of the region. Some faunal species occurring in this region are highly endemic and featuring in Red List of IUCN. They are also protected by the Schedules of Indian Wildlife Protection Act (1972).

This rich biodiversity coupled with higher endemism could be attributed to the humid tropical climate, topographical and geological characteristics, and geographical isolation (Arabian Sea to the west and the semiarid Deccan Plateau to the east). The Western Ghats forms an important watershed for the entire peninsular India, being the source of 37 west flowing rivers and three major east flowing rivers and their numerous tributaries. The stretch of Central Western Ghats of Karnataka, from 12°N to 14°N, from Coorg district to the south of Uttara Kannada district in the north, and covering the Western portions of Hassan, Chikmagalur and Shimoga districts, is exceptionally rich in flora and fauna. Whereas the elevation from 400 m to 800 m, is covered with evergreen to semi-evergreen climax forests and their various stages of degradation, especially around human habitations, the higher altitudes, rising up to 1700 m, are covered with evergreen forests especially along stream courses and rich grasslands in between. This portion of Karnataka Western Ghats is extremely important agriculturally and horticulturally. Whereas the rice fields in valleys are irrigated with numerous perennial streams from forested hill-slopes the undulating landscape is used to great extent for growing precious cash crops, especially coffee and cardamom. Black pepper, ginger, arecanut, coconut, rubber are notable crops here, in addition to various fruit trees and vegetables. Some of the higher altitudes are under cultivation of tea. From the point of productivity, revenue generation, employment potential and subsistence the central Western Ghats are extremely important.The state of Karnataka is a part of the highly biodiversity rich regions of India. The state boasts of a great diversity of climate, topography, soils. It spans the sea coast with its corals and mangrove swamps at the mouths of estuaries. It harbours verdant rain forests, paddy fields and coconut and arecanut orchards on the narrow coast flanked by the hills of Western Ghats. It bears deciduous woods and scrub jungles, and the sugarcane, cotton, groundnut, ragi and jowar fields of the Deccan plateau. The different environmental regimes support their own characteristic set of plants and animals. The lion tailed macaque and the racket tailed drongo are characteristic of the rain forests, the blackbuck and the Great Indian Bustard of the grasslands and scrub jungles of the Deccan plateau.

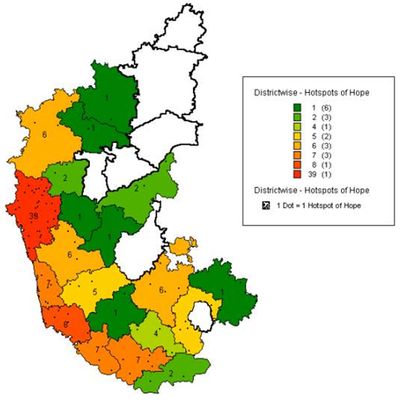

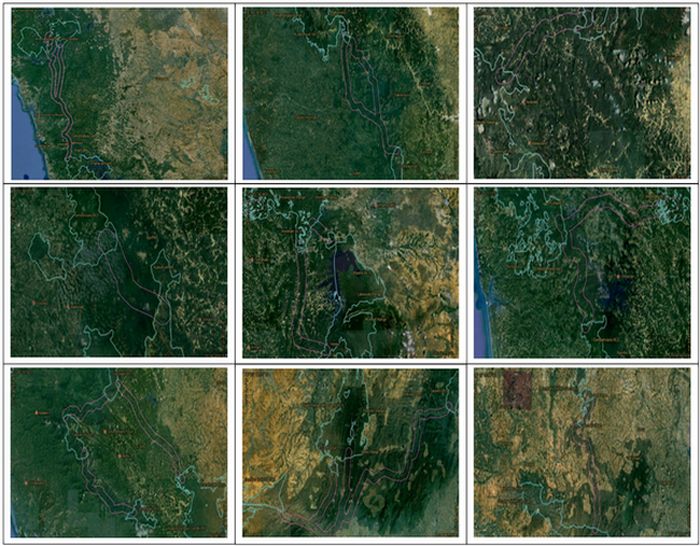

Figure 1: District wise Biodiversity Hotspots of Hope in Karnataka

Table 2: Biodiversity Hotspots of Hope in Karnataka

| SlNo |

District |

Hotspots of Hope |

Hotspots of Despair |

| 1 |

Uttara Kannada |

38 |

18 |

| 2 |

Mysore |

9 |

0 |

| 3 |

Dakshina Kannada |

8 |

16 |

| 4 |

Tumukur |

6 |

2 |

| 5 |

Kodagu |

5 |

3 |

| 6 |

Udupi |

5 |

11 |

| 7 |

Bangalore-Rural |

4 |

2 |

| 8 |

Shimoga |

4 |

2 |

| 9 |

Chamarajanagar |

3 |

1 |

| 10 |

Chikmagular |

3 |

2 |

| 11 |

Belgam |

2 |

5 |

| 12 |

Bellary |

2 |

0 |

| 13 |

Dharwad |

2 |

1 |

| 14 |

Mandya |

2 |

1 |

| 15 |

Bangalore-Urban |

1 |

4 |

| 16 |

Bijapur |

1 |

0 |

| 17 |

Davangere |

1 |

1 |

| 18 |

Hassan |

1 |

0 |

| 19 |

Haveri |

1 |

1 |

| 20 |

Kolar |

1 |

0 |

| 21 |

Bagalkot |

1 |

0 |

Source – Gadgil et al (2005), Status of Karnataka Biodiversity. Sahyadri E-News Issue 11.

However, biodiversity is being eroded in all the major ecosystems of the Karnataka state, in coastal and marine tracts, in streams, rivers, lakes and reservoirs, in protected areas, as also in humid and dry forests outside protected areas, in agro-ecosystems, and in urban ecosystems. This erosion may be traced to four significant environmental problems, namely, (a) non-sustainable harvests of living resources, (b) Habitat destruction and fragmentation, (c) Impacts of pollutants, and (d) Competition with colonizing, often exotic, invasive species. By and large, Karnataka’s biodiversity scenario is characterized by downward trends.

There have however been important initiatives to combat these trends. Thus there is no longer any pressure of commercial exploitation on the evergreen forests of Karnataka. The total forest area of the state has in fact been on increase in recent years. Numbers of important flagship species like the elephant and the tiger have also shown an upward trend in the last few years. Proper implementation of CRZ regulations will result in better protection of beaches and mangrove forests, and of inter-tidal biodiversity in the coming years. Initiatives such the constitution of a Wetlands Authority and an Aquaculture Board may also reverse some of the trends of depletion of fresh-water biodiversity. Mechanisms are being put in place to promote on-farm conservation of crop and livestock genetic resources such as the incentives proposed in the Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act. It is, however, as yet unclear as to how these provisions will be operationalized, and the extent to which they will change the influence the on-going trends. The erosion of traditionally protected species and habitats such as sacred groves, often on private lands is likely to accelerate further. The provisions of the Biological Diversity Act may counteract these trends by creating positive incentives for maintenance of biodiversity. At the same time the shift towards more sustainable agricultural practices may gain ground in the coming years and help reduce the pace of the on-going processes of erosion of agro-biodiversity. The negative trends are, however, likely to be strengthened with rapid growth of urban population and growing demands for urban land as well as the rapidly expanding highway network.

References:

-

Conservation International (2005), Hotspots Revisited: Earth’s Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CI, US, 392 pp.

-

Daniels, R.J.R. (2003), Biodiversity of the Western Ghats: An overview. In ENVIS Bulletin: Wildlife and Protected Areas, Conservation of Rainforests in India, A.K. Gupta, Ajith Kumar and V. Ramakantha (editors), Vol. 4, No. 1, 25 – 40.

-

Gadgil M., Ramachandra T.V., Subhash Chandran M.D., Bhat H.R., et al. (2005), Status of Karnataka Biodiversity. Sahyadri E-News Issue-11.

http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/sahyadri_enews/newsletter/issue11/hotspot/index.htm

-

Nayar, M. P. (1996), “Hot Spots” of Endemic plants of India, Nepal, and Bhutan. SB press, Trivandrum.

-

Sreekantha, Subhash Chandran, M.D., Mesta, D.K., Rao, G.R., Gururaja, K.V. and Ramachandra T.V. (2007), Fish diversity in relation to landscape and vegetation in central Western Ghats, India. Current Science, 92(11): 1592 – 1603.

Biodiversity Hotspots of Hope in Uttara Kannada

| SlNo |

Ecosystem |

Plants |

Animals |

Habitat |

Management Regime |

Geographic Location |

Taluk |

District |

|

Beach |

Marine algae, Spinefex, Ipomoea biloba, adaCanavalia, Hydrophylax maritima |

Marine invertebrates |

Rocky and sandy beach |

|

Mundali |

Bhatkal |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Beach |

Marine algae, Spinefex, Ipomoea biloba, Canavalia, Hydrophylax maritima |

Marine invertebrates |

Rocky beach |

|

Dhareshwar/Vannall |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Beach |

Marine algae, Spinefex, Ipomoea biloba, Canavalia, Hydrophylax maritima |

Marine invertebrates |

Sandy beach |

|

Gudeangidi |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Beach |

Marine algae, Spinefex, Ipomoea biloba, Canavalia, Hydrophylax maritima |

Marine invertebrates |

Sandy beach |

|

Managuni |

Ankola |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Beach |

Marine algae, Spinefex, Ipomoea biloba, Canavalia, Hydrophylax maritima |

Marine invertebrates |

Sandy beach |

|

Honnebail |

Ankola |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Estuary |

|

Fishes, estuarine invertebrates |

Estuary |

|

Sharavathy Estuary |

|

Uttara Kannada |

|

Estuary |

|

Fishes, estuarine invertebrates |

Estuary |

|

Kali |

Karwar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Mesua ferrea |

Lion-tailed Macaque |

Evergreen Forests |

WLS |

Sharavati Valley |

Honnavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus |

Lion-tailed Macaque |

Dipterocarpus indicus Forests |

|

Karikan |

Honavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

|

Karikallani Gudda |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Corypha umbraculifera |

|

Umbrella Palm Forests |

|

Yana |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Riparian flora |

|

Riparian Forests |

|

Aghanashini River bank |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Riparian flora |

|

Riparian Forests |

|

Aghanashini River bank |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Riparian flora |

|

Riparian Forests |

|

Sharavathy bank |

Honavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Riparian flora |

|

Evergreen Forests |

|

Castle Rock |

Joida |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Torme |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Malemane Village |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Hemgar Village |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Kudgund Village |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Hukli Village |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Mahime Village |

Honavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Myristica fatua, Gymnacranthera canarica, Semecarpus travancorica |

Phylloneura westermanii (Monotypic damselfly) |

Myristica Swamps |

|

Harigar & Unchalli |

Sirsi |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Mangrove |

Mangrove vegetation |

|

Mangrove |

|

Honavar |

Honavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Moist Deciduous Forest |

|

|

Moist Deciduous Forest |

WLS |

Dandelli |

Haliyal |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Rocks |

|

|

Rocky Mountain |

Revenue |

Yana |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Sacred Groves |

|

|

Evergreen Forests |

|

Siddapur |

Sorab |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Beach |

|

Olive Ridley Turtle |

Sandy beach |

|

Devbag |

Karwar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

Amphibians |

All |

Reserve Forest |

Sirsi |

Sirsi |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

Amphibians |

All |

Reserve Forest |

Siddapur |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

Amphibians |

All |

Reserve Forest |

Badal |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Estuary |

|

Fishes, estuarine invertebrates |

Estuary |

|

Gangolli |

Honnavar |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Estuary |

|

Fishes, estuarine invertebrates |

Estuary |

|

Aghanashini |

Kumta |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Dodmane |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Devimane |

Sirsi |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Malemane |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Siddapur |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Gerusoppa |

Siddapur |

Uttara Kannada |

|

Evergreen Forests |

Dipterocarpus indicus, Myristica malabarica, Garcinia gummi-gutta |

|

Relic Evergreen Forests |

Reserve Forest |

Yellapur |

Yellapur |

Uttara Kannada |

Source – Gadgil et al (2005), Status of Karnataka Biodiversity.Sahyadri E News Issue – 11, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

ANGIOSPERMS

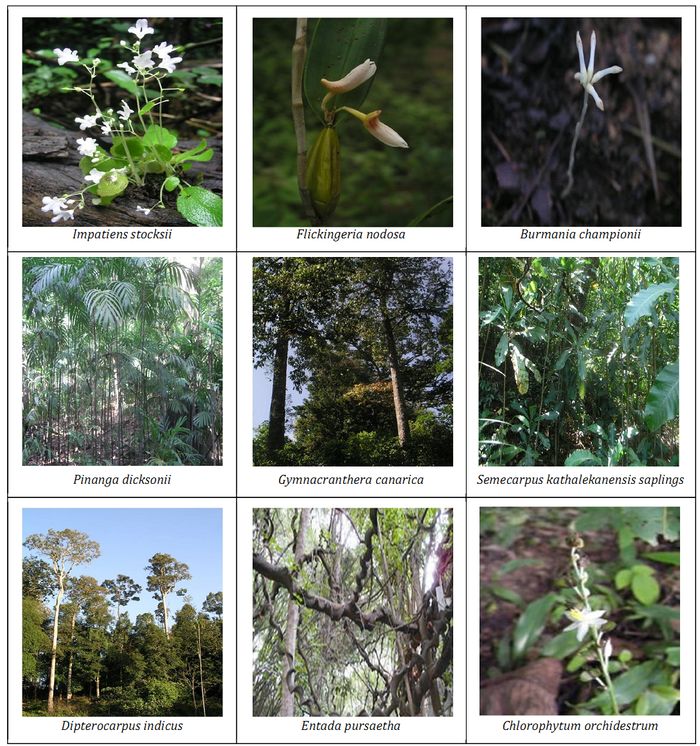

The angiosperms or the flowering plants form a major part of the vegetation on the earth’s surface today and form the biggest group in the plant kingdom. They are highly evolved than the other lower groups of plants and form the basis for successful living of animals and humans on earth. Majority of the medicinal plants in India are higher flowering plants with trees 33 %, shrubs 20 %, herbs 32 %, climber 12 % and others 3 %. They also play a significant role in the economy of the country, providing raw materials for a variety of industries.There are more than 4000 species of flowering plants or angiosperms in the Western Ghats Biodiversity Hotspot (constituting 27% of the Indian flora) of which about 38% are endemics (Ramachandra, 2007). However, depletion of biodiversity at an alarming rate due to anthropogenic activities has necessitated inventorying, monitoring and management. Hence, vegetation and floristic studies have gained increasing importance and relevance in recent years. Many studies time and often have been carried out to document the flowering plant diversity thereby, emphasizing the ecological importance of this hotspot region.

Buchanan (1801) gave a brief general account of the plants he encountered in the course of his journey through the Uttara Kannada district. Bhat et al (1985) carried out plant diversity studies in Uttara Kannada district reported that about two-thirds of reserved forests and minor forests were composed of trees and shrubs while remaining one-third comprised of herbs, climbers, lianas and epiphytes. The overall plant diversity appeared to increase with the increasing extent of distribution with a qualitative change in the plant species composition. Shastri et al (2002) o documented the tree species diversity, species similarity and estimated the standing biomass of species in the Sirsimakki Village Ecosystem in Uttara Kannada district through random sample plots in different types of land use systems. A total of 144 species of trees were found in the entire village ecosystem out of which 93 tree species were found in agro-ecosystem area (including home gardens, paddy and areca garden boundary) and 104 species were recorded on non-agricultural lands such as soppina betta, minor and reserve forest. The values of Sorensen’s Index of home-garden, paddy and areca boundary were lower than the reserve forest, soppina betta and minor forest, indicating less similarity in species composition among them.

Rao et al (2008) documented the floristic diversity of 29 different wetlands in 9 taluks of Uttara Kannada district by random opportunistic sampling. A total of 167 species from 32 families were identified from these localities with Schoenoplectus lateriflorus being the most widely occurring species followed by Cyperus halpan, Geissaspis cristata. Family Cyperaceae was found to be having the highest number of species (50) whereas members of family Eriocaulaceae had the highest number of endemics. Ragihosahalli of Sirsi taluk had the highest number of species diversity with 33 species followed by Shirali of Bhatkal with 32, Haldipur of Honnavar and Hosur of Kumta with 28 species each.

Daniels et al (1993) discussed certain criterias on the basis of which priorities for conservation should be assigned and also highlighted some relevant issues to be taken into account for deciding conservation strategies with respect to Uttara Kannada district. Talking of coastal zone as being richest in biodiversity, they suggested focusing on conservation of Aghanashini estuary which does not receive any effluents and also emphasized that few hectares of each village ecosystem should be dedicated for re-establishment of totally undisturbed patch of natural vegetation.

Shimoga district situated in the heart of Western Ghats is also a rich centre of biodiversity harbouring many important species of flora and fauna. The forest trees of Shimoga district were first catalogued in 1888 by Lovery (1888) and subsequently by Fyson (1915) who worked on the plants of South Indian hill stations describing 58 species of orchids in 24 genera with illustrations. Cooke (1901-1908), Gamble (1915-1936), Pascal (1988), Talbot (1909-1911), Ramaswamy et al (2001), Saldanha et al (1976) and Yoganarasimhan et al (1982) in their publications have given a brief account of the district flora. Ramaswamy et al (2001) gave a comprehensive detail of the flora of Shimoga.

Krishnamurthy et al (2009) carried out a study to document the floristic diversity of the Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary in the central Western Ghats. 30 study sites were selected in the sanctuary and transect based phyto-sociological studies were carried out in each study site and recorded the presence of 406 species of flowering plant belonging to 294 genera and 98 families including 169 species of trees, 82 herbs, 70 climbers and 37 species of shrubs. About 56 species of the plants recorded were found to be endemic to the Western Ghats. At the generic level, Cassia was represented by higher number of species (8) followed by Ficus (6), Ipomoea and Dioscorea (5).

Rao et al (2010) recorded the floristic structure, composition and diversity of the forests affected by varied degrees of human disturbance in Linganamakki catchment region of Sharavathi river basin situated in Shimoga district. A transect consisting of alternate 20 x 20 m quadrats was used for sampling the habitat and the information regarding GPS points, name of locality, human activities like logging, lopping, collection of NTFP, fuel collection, fire incidence, etc. was also collected and recorded. The results showed the presence of 93 tree species, 20 climber species, 33 shrubs, 2 orchids, 13 herb species, and 3 fern species distributed in 64 families and 136 genera. The percentage of evergreeness was high in evergreen and semi-evergreen forests when compared to moist deciduous forests. The moist deciduous forests being rich in timber species were more vulnerable to human exploitation which had led to decrease in their diversity and total basal area.

Kadambi (1939, 1941) had documented the flora of the evergreen forests of Western Ghats giving precise description of the formations between Hassan and Agumbe. The flora of Agumbe-Thirthahalli region was documented by Raghavan (1970, 1983). Saldanha’s work (1984) on Orchidaceae of Hassan district provides description of 95 spp. in 41 genera. In flora of Karnataka, Sharma et al. (1984) listed 173 species of orchids in 51 genera.

Vasanth Raj (2006) studied the distribution and structural aspects of Dipterocarps in the Western Ghats region of Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Coorg districts. In the total sampled area of 2.8 ha spread over seven different forest locations, a total of 209 species of plants belonging to 162 genera and 69 families were recorded. 6 different species of Dipterocarps namely Dipterocarpus indicus, Hopea canarensis, H. parviflora, H. ponga, Vateria indica and Vatica chinensis were recorded in this survey of which except V. chinensis, all other species are endemic to the Western Ghats. The Dipterocarps were found to be dominant members in terms of density, basal area and biovolume in all the seven forests studied. The study also indicated that increasing anthropogenic factors have increased the threat of exploitation of these species resulting in reduction of their numbers.

The orchids are graceful plants belonging to the family Orchidaceae which is one of the largest families of flowering plants. This family is represented by more than 17,000 known wild species in 750 genera in the world and the present figure of the hybrids among these touches around 80,000 (Rao T A., 1998). The orchid diversity is very rich in the central Western Ghats of Karnataka state and has been documented in some earlier works. Wight (1838) made extensive collection from the then known Madras presidency, which included some parts of the present day Karnataka State. This is followed by the work of Hooker (1890-94) who has included about 1200 species from the erstwhile British India. Cooke (1906) while carrying out work on the flora of Bombay presidency made collection chiefly from the then known North Kanara District. Fischer (1928) while completing the work of J S Gamble of the Flora of Presidency of Madras has described 191 species of orchids belongs to 60 genera. Santapau & Kapadia (1966) in their work on the orchids of Bombay have included 100 species from the Uttara Kannada. Saldanha & Nicolson (1976) have enumerated 95 species in 41 genera from Hassan district. This includes a new genus Smithsonia and 4 new species. Rao & Razi (1981) described 62 species belonging to 31 genera from the Mysore district while Arora et al (1981) described 4 species from south Kanara district. Yoganarasimhan et al (1981) recorded 38 species in 26 genera from Chickmagalur district. Sharma et al (1984) have included 173 species in 51 genera from the state while Singh (1981) has recorded 15 species in 6 genera from Eastern Karnataka districts. Keshava Murthy & Yoganarasimhan (1990) have recorded 62 species in 32 genera from Kodagu district. In conservation of wild Orchids of Kodagu in the Western Ghats, Anand Rao (1998) has described 65 species of Orchids.

Table 1: Wild Orchids recorded from Sharavathi River basin and parts of Uttara Kannada district

| S. No. |

Botanical name |

Distribution |

-

|

Aerides maculosum Lindl. |

South-West India. |

-

|

Cottonia peduncularis (Lindl) Reich. |

South-West India, Sri Lanka. |

-

|

Cymbidium bicolor Lindl. |

Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Dendrobium nanum J. Hooker |

South West India |

-

|

Dendrobium ovatum (L.) Kraenclin |

South-West India |

-

|

Eria dalzellii (Dalz.) Lindl. |

Western peninsular India |

-

|

Habenaria crinifera Lindl. |

Western Ghats |

-

|

Habenaria grandifloriformis Blatter & McCann |

Western-Peninsular India |

-

|

Habenaria longicorniculata Grah. |

Western peninsular (India) |

-

|

Malaxis acuminata D. Don |

India, Nepal, and Kampuchea |

-

|

Malaxis rheedii Sw |

India and Sri Lanka |

-

|

Oberonia santapaui Kapadia |

South India |

-

|

Peristylus aristatus Lindl. |

India, Sri Lanka |

-

|

Peristylus secundus(Lindl.) Rathak |

South India |

-

|

Pholidota pallida Lindl. |

Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Plantanthera susane (L.) Lindl. |

Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Polystachya flavescens (Bl.) Sm |

Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Rhynchostylis retusa (L.) Blume, Bijdr. |

Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Aphyllorchis montana Reichb.f. |

Western Ghats. |

-

|

Cleisostoma tenuifolium (L.) Garay |

Western Ghats |

-

|

Dendrobium mabelae Gammie |

S W India. |

-

|

Dendrobium macrostachyum Lindl |

India, Sri Lanka |

-

|

Epipogium roseum (D.Don) Lindl. |

West Africa, Indo-Malaysia |

-

|

Oberonia brunoniana Wt. |

S W India |

-

|

Porpax reticulata |

S W India |

-

|

Porpax jerdoniana (wight) Rolfe |

S W India |

-

|

Zeuxine longilabris (Lindl.) Benth. Ex. Hook.f. |

S W India. |

-

|

Acampe praemorsa (Roxb.) Blatt. and McC. |

India, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka |

-

|

Bulbophyllum neilgherrense Wight |

South India |

-

|

Flickingeria nodosa (Dalz.) Seidenf. |

India Sri Lanka |

-

|

Habenaria heyneana Lindl. |

South India in Western Ghats |

-

|

Nervilia prainiana (King and Pantling) Seidenfaden and Smitin |

India |

-

|

Dendrobium crepidatum Lindl. |

South and North East India |

-

|

Dendrobium lawianum Lindl. |

South West India |

-

|

Diplocentrum congestum Wight |

South West India |

Ramesh et al (2010) described the mesoscale patterns of the floristic composition of the central Western Ghats of Karnataka through 96 1-ha biodiversity plots in the areas of Uttara Kannada, Shimoga and Chikmagalur districts and analyzing the abundance of woody species and the stand structure characteristics. They recorded a total of 61,906 individuals, belonging to 400 plant species (343 trees and shrubs, 56 woody climbers and 1 strangler species) in 254 genera and 75 families from the 96 study plots. The angiospermic plant families Euphorbiaceae, Rubiaceae, Lauraceae and Moraceae were found to constitute 23.5% of the total number of plant species encountered in the study. The principal component analysis revealed that the plots with similar floristic composition can encompass contrasting physiognomic structures which may be probably related to the levels of disturbance.

Many plant species records have been reported and many range extensions of habitats have been observed indicating that this region still holds a great potential for documenting the biodiversity. Clarke (1879) and Gamble (1919) for the first time reported the occurrence of Gymnostachyum polyanthum Wt. belonging to family Acanthaceae in the Coorg district. Later Sharma et al (1984) reported this plant from Shimoga region of Karnataka. Bhat (2005) reported the presence of Ceraciocarpum bennetti (Miq.) Cogn.belonging to family Cucurbitaceae for the first time from Karnataka state. Hegde & Shripathy (2005) rediscovered Chirita hamosa R. Br. and Kaempferia sccaposa Benth. belonging to Zingiberaceae from Karnataka state. Hegde et al (2010) gave the additional descriptions of Gymnostachyum polyanthum Wt. and Ceraciocarpum bennetti (Miq.) Cogn recorded during an extensive floristic diversity inventorisation in Uttara Kannada and Udupi districts of Karnataka.

Marsdenia raziana Yogan.& Subram was first collected in 1970 from Yelnir forests of Western Ghats in Chikmagalur district and was described by Yoganarsimhan et al (1976). Later it was collected from Agumbe Ghats and Kannur in Kerala and was described as a rare climber endemic to the Western Ghats of Karnataka and Kerala by Ravikumar & Udayan (2002). Raghavan & Kulkarni (1980) collected and described a new species of Dalechampia namely Dalechampia stenoloba Raghavan & Kulkarni sp. Nov. from the forests of Lakavalli taluk in Chikmagalur district. Krishnakumar & Kaveriappa (1999) collected and described Hopea canarensis from Kudremukh region in Karnataka. According to them, this species is considered as a narrow endemic species of Western Ghats and is mostly confined to Dakshina Kannada and Chikmagalur districts of Karnataka. Semecarpus kathalekanensis, a new tree species of Anacardiaceae was described from the swamps of Kathalekan (Dasappa & Swaminath 2000). Ravikumar & Udayan (2002) collected Marsdenia raziana Yogan. & Subram. of family Asclepiadaceae from Agumbe and Kannur region in Karnataka thereby describing the extended distribution of this endemic species. Bhaskar (2006) reported a new scapigerous epiphytic species of Impatiens namely Impatiens clavata Bhaskar sp. nov. from the Bisle - Subrahmanya road in Sakaleshpur taluk of Hassan district in Karnataka.

Recent discovery of two Critically Endangered trees Madhuca bourdillonii and Syzygium travancoricum from some relic forests of Uttara Kannada, almost 700 km north of their recorded home range in southern Kerala emphasized the need for locating more relic forest patches and investigating them (Chandran et al, 2008). Dessai et al (2009) illustrated and described a new species, Impatiens bhaskarii from the Western Ghats of Charmadi ghat region in Chikmagalur district of Karnataka. This is an endemic species and confined to the Western Ghats of Karnataka. Mesta et al (2009) collected and reported Cassipourea ceylanica (Gardn.) Alston after a gap of 130 years from the first report of its occurrence in Karnataka. Current specimen was reported along a stream bank in the evergreen forest patch of Ankola taluk in Uttara Kannada district.

Ali et al (2010) reported the occurrence of Burmannia championiiThw., a saprophytic herb, for the first time in Karnataka from a Myristica swamp in Uttara Kannada district, thereby extending its northern limit of distribution in Western Ghats. Mascarenhas & Janarthanam (2010) described and illustrated a new variety Rungia linifolia Nees var. saldanhae Mascar. & Janarth.belonging to family Acanthaceae from Charmady ghat in Karnataka. Shimpale & Yadav (2010) described an undescribed plant species Eriocaulon belgaumensis of family Eriocaulaceae from Western Ghats region of Kakumbi plateau in Belgaum district. During a botanical exploration in Anshi National Park, Uttara Kannada district, Punekar and Lakshminarasimhan (2010) observed and described a new species Stylidium darwinii Punekar & Lakshmin belonging to family Stylidaceae.

Table 2: Important Angiosperms of Central Western Ghats with their Conservation status

| Sr. No. |

Family |

Botanical Name |

Habit |

IUCN status |

-

|

Meliaceae |

Aglaia elaeagnoidea |

Tree |

Lower Risk |

-

|

Calophyllaceae |

Calophylum tomentosum |

Tree |

Vulnerable |

-

|

Sapindaceae |

Dimocarpus longan |

Tree |

Near Threatened |

-

|

Ebenaceae |

Diospyros crumenata |

Tree |

Endangered |

-

|

Dipterocarpaceae |

Dipterocarpus indicus |

Tree |

Endangered |

-

|

Myristicaceae |

Gymnacranthera canarica |

Tree |

Vulnerable |

-

|

Myristicaceae |

Knema attenuata |

Tree |

Lower Risk |

-

|

Sapotaceae |

Madhuca bourdillonii |

Tree |

Endangered |

-

|

Myristicaceae |

Myristica magnifica |

Tree |

Endangered |

-

|

Caesalpinaceae |

Saraca asoca |

Tree |

Vulnerable |

-

|

Myrtaceae |

Syzygium travancoricum |

Tree |

Cr. Endangered |

-

|

Dipterocarpaceae |

Vateria indica |

Tree |

Cr. Endangered |

-

|

Dipterocarpaceae |

Vatica chinensis |

Tree |

Cr. endangered |

Figure 1 – Some important angiosperms of Western Ghats

References:

- Arora R.K., (1961, 62, 63), The forests of the North Kanara district, Journal of the Indian Botanical Society, vol. 40, 41, 42.

- Bhaskar V. (2006), Impatiens clavata Bhaskar sp. nov. – a new scapigerous balsam (Balsaminaceae) from Bisle Ghat, Western Ghats, South India. Current Science, 91(9): 1138-1140.

- Bhaskar V. and Razi B.A. (1973), Hydrophytes and Marsh plants of Mysore city. Prasaranga Univ Mysore.

- Bhat K.G. (2005), Additions to the flora of Karnataka. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 102(3): 383.

- Bhat D.M., Prasad S.N., Hegde M. and Saldanah C.J. (2000), Plant diversity studies in Uttara Kannada district, CES Technical Report no.9, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

- Buchanan F.D. (1801), Journey through the northern parts of Kannara.

- Buchanan F.D. (1870), A Journey from Madras through the countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar, Vol. 2. Higginbothams and Company, Madras.

- Chandran M. D. S, Mesta D. K., Rao G. V., Sameer Ali, Gururaja K. V. and Ramachandra T. V. (2008), Discovery of two critically endangered tree species and issues related to Relic forests of the Western Ghats, The Open Conservation Biology Journal, 2: 1-8.

- Clarke C.B. (1879), Cucurbitaceae. In: Flora of British India (by Hooker J.D.) Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehradun. Vol.2, pg. 629.

- Cooke, T. (1901-1908). Flora of Presidency of Bombay, 3 Vols. Taylor and Francis, London.

- Daniels R.J.R., Chandran M.D.S. and Gadgil M. (1993), A strategy for conserving the biodiversity of Uttara Kannada district in South India. Environmental Conservation, 20(2): 131-138.

- Dasappa and Swaminath M.H. (2000), A new species of Semecarpus (Anacardiaceae) from the Myristica swamps of Westrn Ghats of North Kanara, Karnataka, India. Indian Forester 126, 78-82.

- Fyson, P.F (1915). The Flora of the Nilgiri and Pulney hill-tops (above 6,500 feet), Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehra Dun.

- Gamble J.S. (1919), Flora of the Presidency off Madras. Adlard and Son, London, pg. 541 – 542.

- Gamble, J. S. (1915-1936), Flora of the Presidency of Madras. Adlard and Son, London.

- Hegde G.R. and Shripathy V. (2005), Plants of interest in the districts of Karnataka existed under Presidency of Bombay. In: Plant Taxonomy: Advances and Relavance (Pandey A.K., Jun Van and J.V.V. Doga) CBS Publishers and Distributors, New Delhi. P. 355 – 361.

- Hegde G.R., Prakash D., Hebbar S.S., Bhat K.G. and Hegde G.R. (2010), Additional descriptions to two newly recorded plants from Karnataka. Indian Forester, 136(1): 117 – 122.

- Kadambi, K. (1939), The montane evergreen forests of Bisle region. Indian For.

- Kadambi, K. (1941), The evergreen Ghat rain forest. Agumbe-Kilandur zone. Indian For.

- Krishnamurthy Y.L., Prakasha H.M. and Nanda A. (2009), Floristic diversity of the Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary. Indian Forester.

- Krishnakumar G. and Kaveriappa K.M. (1999), Hopea canarensis Hole: A little known species of Western Ghats, India. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 11(2): 337-344.

- Lovery E. P. (1888), Catalogue of forest trees growing in Shimoga district. 1-50, Bangalore.

- Mascarenhas M.E. and Janarthanam M.K. (2010), A new variety of Rungia linifolia (Acanthaceae) from the Western Ghats of Karnataka, India. Novon, 20(2): 182-185.

- Murthy K.K.R. (1986), Studies on the flora of Coorg (Kodagu) district, Karnataka. PhD thesis, Department of Botany, University of Mysore, Mysore.

- Pascal, J. P. (1988), Wet Evergreen forests of the Western Ghats of India-Ecology, Structure, Floristic composition, and Succession. Sri Aurobindo Ashram press, Pondicherry.

- Raghavan, R.S. (1970), The Flora of Agumbe and Tirthahalli areas in Shimoga district, Mysore State. 3 Vols. Ph.D. thesis. Univ. Madras.

- Raghavan R.S. and Kulkarni B.G. (1980), A new species of Dalechampia (Euphorbiaceae) from peninsular India. Kew Bulletin, 35(2): 323 – 325.

- Ramachandra T.V. (2007), Vegetation status in Uttara Kannada district. MJS, 6(7): 1-26.

- Ramachandra T.V., Chandran M.D.S, Bhat H.R., Dudani S., Rao G.R., Boominathan M., Mukri V. and Bharath S. (2010), Biodiversity, Ecology and Socio-economic significance of Gundia River basin in the context of proposed Mega Hydro electric power project. CES Technical Report-122, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

- Ramaswamy, S.N., Radhakrisna Rao, M. and Govindappa, D.A. (2001), Flora of Shimoga District. Karnataka.University printing press, Mysore.

- Ramesh B.R. and Pascal J.P. (1997) Atlas of the Endemics of the Western Ghats (India). French Institute, Pondicherry, 403 pp.

- Ramesh B.R., Venugopal P.D., Pelissier R., Patil S.V., Swaminath M.H. and Couteron P. (2010), Mesoscale patterns in the floristic composition of forests in the Central Western Ghats of Karnataka, India. Biotropica, 42(4): 435-443.

- Rao G. R., Subhashchandran M. D. and Ramachandra T. V., (2005), Habitat approach for conservation of herbs, shrubs, and climbers in the Sharavathi River Basin, The Indian Forester, 131 (7): 885-900

- Rao G.R., Mesta D.K., Subhashchandran M.D. and Ramachandra T.V. (2008), Wetland Flora of Uttara Kannada, Environment Education for Ecosystem Conservation, pp. 152 – 159.

- Rao G.R., Subash Chandran M.D. and Ramachandra T.V., (2010), Plant Diversity in the Sharavathi River Basin in Relation to Human Disturbance. The Indian Forester 136(6): 775-790.

- Rao Anand T., 1998. Conservation Of Wild Orchids Of Kodagu In The Western Ghats. The Karnataka Association for the Advancement of Science, Bangalore.

- Rao R.M. (1990), Studies on the flora of Shimoga district. PhD thesis, Department of Botany, University of Mysore, Mysore.

- Ravikumar K. and Udayan P.S. (2002), Notes on Marsdenia raziana Yogan. &Subram., a Karnataka and Kerala Western Ghats endemic.Zoos’ Print Journal, 17(12): 949-950.

- Saldanah C.J. and Nicolson D.H. (1976), Flora of Hassan district, Karnataka, India. Amerind Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

- Saldanha C. J. (1984), Flora of Karnataka. 2 Volumes. Oxford and IBH Publishing Co., New Delhi.

- Sameer Ali, D.K. Mesta, M.D. Subash Chandran and T. V. Ramachandra, (2010), Report of Burmannia Championii Thw. From Uttara Kannada, Central Western Ghats, Karnataka. J. Econ. Taxon. Bot. Vol. 34 No. 2 (2010).

- Santapau (1955), Indian Botanical Society Excursion, Journal of Indian Botanical Society, 30: 181 – 191.

- Sharma B.D., Singh N.P., Raghavan R.S. and Deshpande U.R. (1984), Flora of Karnataka, Analysis. Botanical Survey of India.

- Shastri C.M., Bhat D.M., Nagaraja B.C., Murali K.S. and Ravindranath N.H. (2002), Tree species diversity in a village ecosystem in Uttara Kannada in Western Ghats, Karnataka. 82(9): 1080-1084.

- Talbot, W.A (1909). Forest flora of the Bombay Presidency and Sind. Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh, Dehra Dun.

- Talbot, W.A. (1911). Forest Flora of the Bombay Presidency and Sind. Vol. 2 (Poona: Government Photozicographic Press).

- Vasanth Raj B.K. (2006), Structural studies of some Dipterocarp forests of Western Ghats of Karnataka. PhD thesis, Department of Applied Botany, Mangalore University.

- Yoganarasimhan S.N., Subramanyam K. and Razi B.A. (1981), Flora of Chikmagalur district. International Book distributors, Dehradun.

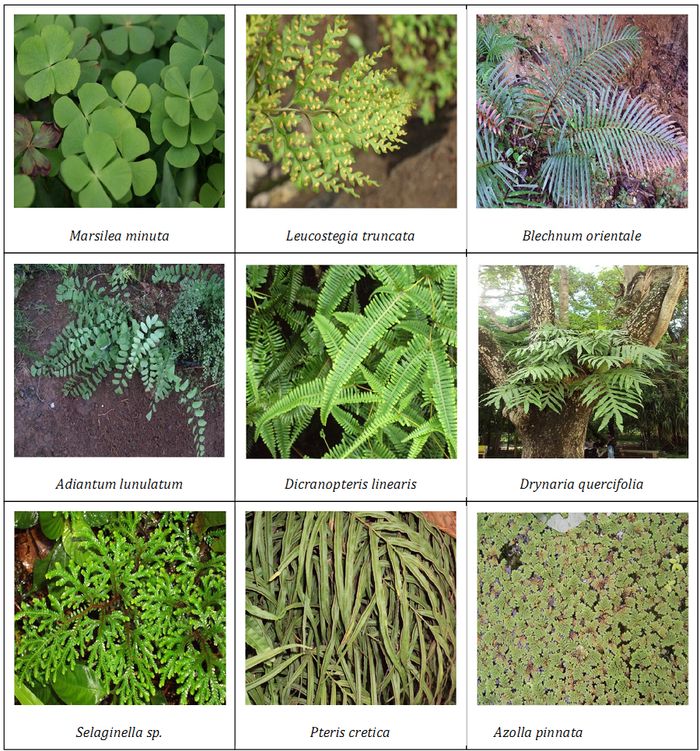

PTERIDOPHYTES

Pteridophytes are the most primitive vascular cryptogams and include ferns and fern-allies. They form a conspicuous element of the earth’s vegetation and are important from evolutionary point of view as they show the evolution of vascular system and reflect the emergence of seed habitat in the plants. . They were the first vascular plants to grow on the surface of earth and began their life period from leafless and rootless individuals (with photosynthetic stem and rhizoids performing the function of roots) in the Silurian and Devonian periods. As they show the evolution of vascular system and reflect the emergence of seed habitat in the plant, they are considered to be a vital link between the lower cryptogam group of plants and higher spermatophyte group of plants (Dudani et al, 2011). They played an important role in establishing the early land flora as they emerged shortly after the evolution of land plants and are much larger than bryophytes (Kenrick & Crane, 1997).

Pteridophytes grow luxuriantly in moist tropical forests and temperate forests and their occurrence in different eco-geographically threatened regions from sea level to the highest mountains are of much interest (Dixit, 2000). Though they have been largely replaced by the spermatophytes in the modern day flora, they continue to occupy an important and crucial position in the evolutionary history of the plant kingdom. India has a rich and varied pteridophytic flora due to its diversified topography, variable climatic conditions and its geographical position with several migration-flows of species of different phytogeographical elements meeting in different parts of the Country. They occur in a variety of habitats like terrestrial (Equisetum, Selaginella), aquatic (Azolla, Marsilea), epiphytic (Lepisorus, Drynaria) and lithophytic (Psilotum, Adiantum).

The world flora consists of approximately 12, 000 species of pteridophytes of which around 1000 species distributed in 70 families and 192 genera are likely to occur in India. The major distribution of pteridophytes can be observed in the Himalayas, Western Ghats, Eastern Ghats and Panchmarhi Biosphere Reserve. The Western Ghats form an important habitat for the ferns and fern-allies and hence, they are one of the important biodiversity centers rich in pteridophytic diversity. About 300 species of pteridophytes are figured to be present in the Western Ghats. They depend upon the microclimatic conditions of the region and any disturbance in it may have adverse effects on their population. Each species of fern has its own preferences for temperature, humidity, soil type, moisture, pH, light levels etc., and in many cases are very specific indicators of the conditions they need (Shaikh & Dongare, 2009).

Some noticeable studies which had been carried out in this region include the collection and listing of 75 species of ferns from North Canara (Uttara Kannada) district by Matchperson (1890). Later, in 1992, Blatter & Almeida included 90 species of ferns from Uttara Kannada district, then a part of Bombay Presidency, in their “Ferns of Bombay”. Alston (1945) recorded 58 species of Selaginella from India of which 4 species have been recorded from Karnataka. Kammathy et al (1967) listed 25 species of ferns and fern-allies in their “Contribution towards a Flora of Biligirirangana Hills”. Razi & Rao (1971) published an artificial key to the Pteridophytes of Mysore city and its neighbouring areas in which they included 70 species of ferns and fern-allies spread over 41 genera. Bhaskar & Razi (1973) recorded 7 species of ferns and one species of Selaginella from aquatic and semi-aquatic habitats of Mysore district.

Holttum (1976) included 10 members of Thelypteridaceae in the “Flora of Hassan District”. Yoganarsimhan et al (1981) recorded 12 species of ferns in their “Flora of Chikmagalur District”. However, the only in depth and comprehensive work on the pteridophytes of Karnataka has been done by Rajagopal and K.G. Bhat (1998) by gathering data on Pteridophyte diversity of Karnataka state from 1988-1995. Ramachandra et al (2010) documented the presence of 54 different species of pteridophytes from the Gundia river basin. There have been very few studies on the ecological aspects of this group of plants and hence, more research needs to be done to develop conservation strategies for them.

References:

- Bhaskar V. and Razi B.A. (1973), Hydrophytes and Marsh plants of Mysore city. Prasaranga Univ Mysore.

- Blatter E. and Almeida J.F.D (1992), The Ferns of Bombay. D.B. Taporevala Sons & Co., Bombay.

- Chandra, S., Fraser-Jenkins, C.R., Kumari Alka and Srivastava, A. (2008). A summary of status of threatened pteridophytes of India. Taiwania, 53(2): 170-209.

- Dixit R.D. (2000), Conspectus of Pteridophytic diversity in India. Indian Fern Journal, 17: 77 – 91.

- Dudani S.N., Chandran M.D.S., Mahesh M.K. and Ramachandra T.V. (2011), Diversity of Pteridophytes of Western Ghats. Sahyadri E-News Issue-33.

http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/sahyadri_enews/newsletter/issue33/index.htm

- Holttum R.E. (1976), Thelypteridaceae, In: Saldanah C.J. and Nicolson D.H. (Eds), Flora of Hassan district of Karnataka, India. Amerind Publishing Co Pvt Ltd, New Delhi.

- Kammathy R.V., Rao A.S. and Rao R.S. (1967), A contribution towards Flora of Biligirirangan Hills, Mysore state. Bull Bot Surv India, 9(1-4): 206-234.

- Kenrick P. and Crane P.R. (1997), The origin and early evolution of plants on land. Nature, 389: 33-39.

- Matchperson T.R.M. (1986), List of ferns gathered in North Kanara. J Bomb Nat Hist Soc, 5: 375-377.

- Rajagopal P. K. and Bhat K. G. (1998), Pteridophyte flora of Karnataka state, India. Indian Fern Journal, 15: 1 – 28.

- Ramachandra T.V., Chandran M.D.S, Bhat H.R., Dudani S., Rao G.R., Boominathan M., Mukri V. and Bharath S. (2010), Biodiversity, Ecology and Socio-economic significance of Gundia River basin in the context of proposed Mega Hydro electric power project. . CES Technical Report-122, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

- Saldanah C.J. and Nicolson D.H. (1976), Flora of Hassan district, Karnataka, India. Amerind Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

- Shaikh S.D. and Dongare M. (2009), The influence of microclimatic conditions on the diversity and richness of some ferns from the North-Western Ghats of Maharashtra. Indian Fern Journal, 26: 128 – 131.

- Yoganarasimhan S.N., Subramanyam K. and Razi B.A. (1981), Flora of Chikmagalur district. International Book distributors, Dehradun.

Table 1: Pteridophytes recorded from Uttara Kannada district

| Sr. No. |

Botanical Name |

Family |

Occurence |

-

|

Lycopodium cernum L. |

Lycopodiaceae |

Kaiga |

-

|

L. hamiltonii |

Siddapur |

-

|

Selaginella delicatula (Desv. Ex Poiret) Alston |

Selaginellaceae |

Castle rock, Dandeli, Londa and Anmode |

-

|

S. miniatospora (Dalz.) Baken |

Castle rock |

-

|

S. proniflora (Lam.) Baker |

Kaiga |

-

|

S. tenera (Hook. & Grev.) Spring |

Sirsi and Kaiga |

-

|

Psilotum nudum (L.) P. Beauv. |

Psilotaceae |

Kaiga |

-

|

Ophioglossum costatum R. Br. |

Ophioglossaceae |

Yellapur-Sirsi bridge side & Kadra-Kodasali road |

-

|

O. reticulatum |

Kaiga |

-

|

Osmunda regalis L. |

Osmundaceae |

Anmode, Jog and Samse |

-

|

Lygodium flexosum (L.) Sw. |

Schizaeceae |

Jog falls and Dandeli |

-

|

L. microphyllum |

Castle rock |

-

|

Acrostichum aureum L. |

Pteridaceae |

Karwar |

-

|

Pteris biaurita L. |

Castle rock |

-

|

P. linearis Poriet |

Castle rock |

-

|

P. pellucida Presl. |

Castle rock, Siddapur and Kaiga |

-

|

P. quadriaurita Retz. |

Castle rock and Jog |

-

|

P. semipinnata L. |

Anmode |

-

|

P. vittata L. |

Castle rock |

-

|

Cheilanthes tenuifolia (Burm.) Sw. |

Sinopteridaceae |

Londa, Jog and Kaiga |

-

|

Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn. |

Parkeriaceae |

Londa, Karwar and Dandeli |

-

|

Pityrogramma calomelanos (L.) Link |

Hemionitidaceae |

Gerusoppa |

-

|

Adiantum lunulatum Burm. F. |

Adiantaceae |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

Vittaria elongate Sw. |

Vittariaceae |

Yellapur |

-

|

Microlepia speluncae (L.) Moore. |

Dennstaeditiaceae |

Kathalekan |

-

|

Pteridium aquilinium (L.) Kuhn. |

Castle rock |

-

|

Lindsaea ensifolia Sw. |

Lindsaeceae |

Castle rock and Sirsi |

-

|

L. heterophylla Dryander |

Gerusoppa, castle rock and Shivapura |

-

|

Leucostegia immerse (Wallich ex Hook.) Presl |

Davalliaceae |

Gerusoppa |

-

|

Trichomanes intramarginale Hook. & Grev. |

Hymenophyllaceae |

Kaiga |

-

|

Dicranopteris linearis (Burm. f.) Underwood |

Gleicheniaceae |

Castle rock, Londa and Jog falls |

-

|

Cyathea gigantea (Wallich ex Hook.) Holttum. |

Cyatheaceae |

Gerusoppa and Castle rock |

-

|

Thelypteris (Ampelopteris) prolifera (Retz.) Copel. |

Thelypteridaceae |

Kaiga |

-

|

T. (Amphineuron) terminans (Hook.) Holttum |

Yellapur |

-

|

T. (Christella) dentate (Forsk.) Brownsey and Jermy |

Kaiga and Castle rock |

-

|

T. (Christella) hispidula Holttum |

Kaiga |

-

|

T. (Christella) papilio (Hope) Holttum |

Kaiga |

-

|

T. (Christella) parasitica (L.) Leveille |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

T. (Cyclosorus) interruptus (Willd.) |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

Asplenium inaqeilaterale Willd. |

Aspleniaceae |

Jog falls |

-

|

A. nidus L. var. phyllitidis (D.Don) Bir |

Sirsi |

-

|

Anisocampium cumingianum Presl |

Athyriaceae |

Nagergoli |

-

|

Athyrium anisopterum Christ. |

Castle rock and Gerusoppa |

-

|

A. hohenackerianum (Kunze) T. Moore |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

A. solenopteris (Kunze) T. Moore |

Gerusoppa |

-

|

Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw. |

Jog falls and Castle rock |

-

|

Dryopteris cochleata C. Chr. |

Dryopteridaceae |

Castle rock |

-

|

Tectaria coadunata (J. Smith) C. Chr. |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

Bolbitis appendiculata var. appendiculata (Willd.) K. Iwatsuki |

Lomariopsidaceae |

Anmoda and Castle rock |

-

|

B. lancea (Coepl.) Ching |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

B. presliana (Fee) Ching |

Castle rock and Kaig |

-

|

B. prolifera (Bory) C. Chr |

Castle rock |

-

|

B. semicordata(Baker) Ching |

Gerusoppa |

-

|

B. subcrenata (Hook. & Grev.) Ching |

Castle rock and Kaiga |

-

|

Blechnum orientale L. |

Blechnaceae |

Katgal and Castle rock |

-

|

Stenochlaena palustris (Burm.) Beddome |

Katgal and Yana |

-

|

Drynaria quercifolia (L.) f. |

Sirsi and Kaiga |

-

|

Lepisorus nudus (Hook.) Ching |

Castle rock and Gerusoppa |

-

|

Leptochilus decurrens Blume |

Jog falls and Kaiga |

-

|

Loxogramme involuta (D. Don) Presl |

Gerusoppa |

-

|

Microsorum membranaceum (D. Don) Ching |

Jog falls |

-

|

M. punctatum (L.) Coepl. |

Jog falls |

SOME PTERIDOPHYTES FOUND IN CENTRAL WESTERN GHATS

FUNGI

The fungi are a very important group of organisms both from the ecological and economical point of view. They degrade the organic substances and thus, help in continuation of nutrients in the ecosystem. Their fermentation properties are used for the formation of a number of products which are of great economical importance. They form a vital source of food and nourishment and hence, are consumed on large scale by humans in different forms. In the forest ecosystem, the ectomycorrhizal or endomycorrhizal associations with the roots of higher plants and thus, help in their adaptation to the environment. The fungi are key functional components of the forest ecosystems and in spite of this, very little are known about the diversity and landscape distribution of this group of organisms. The effects of forest disturbance and habitat fragmentation have not been studied properly on this group of organisms.

One of the main reasons responsible for the lack of information about the fungi is the formidable difficulty they present to the ecological study (Cannon, 1997). However, some studies in recent past have been carried out on the fungal groups in the central Western Ghats. Vijay Kumar (1995) documented 103 different species of aquatic fungi belonging to 83 genera from Uttara Kannada district. He pointed out that the occurrence of water borne fungi was affected by rainfall, water temperature and availability of leaf litter and maximum species was collected during the monsoon season.

Rajashekhar & Kavveriappa (1996) studied the occurrence of aquatic hyphomycetes in the Panekal Suphur spring in Dakshina Kannada district of Karnataka by using leaf litter incubation method and analysis of natural foam and induced foam. A total of 16 species belonging to 13 genera were recorded from the outflow sites of the spring with Triscelophorus monosporus being the most frequent organism. The study indicated that high sulfide content along with high temperature was responsible for total absence of hyphomycetes in proper sulfur spring water.

Bhat (1999)studied the rhizosphere mycoflora including the arbuscular mycorrhizae and rhizoplane regions in five selected tree species of Myristicaceae family in the Kathalekan forests of Uttara Kannada district. A total of 49 species of fungi were isolated from the non-rhizosphere soils of the study region while a total of 99 species of fungi were isolated from the rhizosphere of selected tree species with 34 species being common to the rhizosphere of all the trees. The analysis of rhizoplane showed the presence of 37 species of fungi whereas the Arbuscular Mycorrhyzal fungi (AMF) isolated from the rhizosphere represented 57 different species and 6 different genera. the statistical analysis revealed a significant correlation between rhizosphere and rhizoplane fungi population and pH, temperature, MC, OM and EC of the rhizosphere soil of individual tree species in different seasons.

Soosamma et al (2001) collected an aquatic fungi in the foam and submerged coffee leaves from a stream in a coffee plantation in Somwarpet, Kodagu District which was found to be possessing triradiate conidia with a recurved arm. As this fungus was undescribed, the authors described it as a new taxon of Trinacrium identified as Trinacrium indica Soosamma, Lekha, Sreekala & Bhat, sp. nov.

Lakshmipathy et al (2003) investigated the Vesicular Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (VAM) colonization pattern in some rare, endangered and threatened medicinal plants in different part of Western Ghats of Karnataka. In general, the VAM colonization was found to be more from the samples of Western Ghats region compared to the samples of coastal region. The VAM colonization was also found to be related to pH, phosphorous content and phosphatase activity in the root soil zone.

Madhusoodhanan (2003) isolated 68 different Arbuscular mycorrhizal species from 56 different plant species in iron rich soil of Western Ghats region in Kudremukh National Park. 15 plant species were selected and a total of 87 different types of AM spores were isolated from iron-rich and normal soils. The density of the AM spores varied from plant species to plant species and from season to season in iron-rich and normal soils. A significant correlation was also observed between the spore number and root colonization.

Rajashekhar & Kaveriappa (2003) analysed the relationship between the physic-chemical parameters of water, riparian vegetation, altitude and species richness of the fungi of group Hyphomycetes in six rivers and a sulfur spring of the Western Ghats in Karnataka. The most abundant species were found to be Anguillospora longissima, Helicomyces roseus, Lunulospora curvula, Triscelophorus monosporus and Wiesneriomyces laurinus. Generally, the indices of similarity in the mycoflora were found to be high between the streams.

Brown et al (2006) studied the effects of disturbance and fragmentation on the diversity and landscape distribution of the macrofungal group in the Western Ghats of Kodagu region in Karnataka. They recorded the macrofungi on three occasions over a wet season in forest reserve sites, sacred groves and coffee plantations and found that the sacred groves had the highest sporocarp abundance and the greatest morphotype richness per sample area whereas the coffee plantations were more diverse for a given number of sporocarps. The study also indicated that there was no significant correlation between dissimilarity in macrofungal assemblages and geographical distances between the sample sites.

Mallikarjuna Swamy (2007)studied the fungal diseases and its effects on the medicinally important plant species in the Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary of central Western Ghats in Karnataka. A survey was conducted to record the medicinal tree species in the study area and the pathogenecity of all fungal species associated with disease symptoms of different plant parts was conducted on leaves and stems of respective tree species. The results revealed the presence of 224 different fungal species associated with the surfaces of diseased samples of tree species with the commonly occurring dominant fungi being the species of Alternaria, Cercospora, Collelotrichum, Fusarium, Macrophomina, Pestalotiopsis and Phoma. The disease occurrence in different trees was found to be varying in different seasons depending upon the pathogenic species, vegetation pattern in state forest regions and respective host species. Rainfall, humidity and temperature played a significant role in causing the fungal diseases as well as deciding its severity. The phytochemical analyses of the plant materials revealed that the content of steroids and alkaloids decreased significantly in both partially affected and totally affected diseased samples whereas the flavonoid and phenol content was found to be decreasing with the increase in percentage of infection.

Swapna et al (2008) studied the diversity of macrofungi in the semi evergreen and moist deciduous forests of Shimoga district in Karnataka. They recorded the presence of a total 778 species of macrofungi belonging to 101 genera and 43 families. 280 genera of macrofungi belonging to 41 families and 19 orders were recorded from the moist deciduous forests with Basidiomycetes being the dominant group followed by Ascomycetes and Myxomycetes. The overall macrofungal diversity was found to be higher in high elevations of semi-evergreen forests than in the intermediate altitudes of moist deciduous forests.

Reddy et al (2005)reported a new ectomycorrhizal fungi species Pisolithus indicus associated with the endemic tree Vateria indica (Dipterocarpaceae) from a Dipterocarp native forest in the central Western Ghats of Uppangala in Coorg district. Yadav & Bhat (2009) isolated a coprophilous fungus, Dimastigosporium yanense sp. novfrom the cattle dung collected from the forests of Western Ghats in Karrnataka. Senthilarasu et al (2010) collected and described a new species of fungi, Hygrocybe natarajanii from the Uppanagala forests in Coorg districts of Karnataka.

References:

- Bhat P.R. (1999), Studies on the rhizosphere mycoflora of some species of Myristicaceae in Western Ghats. PhD thesis, Department of Applied Botany, Mangalore University.

- Brown N., Bhagwat S. and Watkinson S. (2006), Macrofungal diversity in fragmented and disturbed forests of the Western Ghats of India. Journal of Applied Ecology, 43: 11-17.

- Lakshmipathy A., Gowda B. and Bagyaraj D.J. (2003), VA mycorhizal colonization pattern in RET medicinal plants (Mammea suriga, Saraca asoca, Garcinia spp., Embelia ribes and Calamus sp) in different parts of Karnataka. Asian Journal of Microbiology, Biotechnology and Environmental Sciences, 5(4), 505 – 508.

- Madhusoodhanan P.C. (2003), Studies on arbuscular mycorrhizae of selected species of plants in Kudremukh region of Western Ghats. PhD thesis, Department of Applied Botany, Mangalore University.

- Mallikarjun Swamy G.E. (2007), Studies on Fungal diseases of Medicinally important plant species in Bhadra wildlife sanctuary. PhD thesis, Department of Postgraduate studies and research in Botany, Kuvempu University, Shimoga.

- Rajashekhar M. and Kaveriappa K.M. (1996), Aquatic Hyphomycetes of a Sulfur spring in the Western Ghats, India. Microbiaal Ecology, 32(1): 73-80.

- Reddy M.S., Singla S., Natarajan K. and Senthilarasu G. (2005), Pisolithus indicus a new species of ectomycorrhizal fungus associated with Dipterocarps in India. Mycologia, 97(4): 838 – 843.

- Senthilarasu G., Kumaresan V. and Singh S.K. (2010), A new species of Hygrocybe in section Firmae from Western Ghats, India. Mycotaxon, 111: 301-307.

- Soosamma M., Lekha G., Sreekala K.N. and Bhat D.J. (2001), A new species of Trinacrium from submerged leaves from India. Mycologia, 93(6): 1200 – 1202.

- Swapna S., Syed A. and Krishnappa M. (2008), Diversity of macrofungi in semi evergreen and moist deciduous forests of Shimoga district – Karnataka, India. J Mycol Pl Pathol, 38(1): 21 – 26.

- Vijaya Kumar S. (1995), Studies on water borne fungi of Uttara Kannada district. PhD thesis, Department of Botany, Karnatak University, Dharwad.

- Yadav S. and Bhat D.J. (2009), Dimastigosporiumyanense, a new coprophilous fungus from the forests of Western Ghats in Karnataka State, India. Mycotaxon, 107: 397-403.

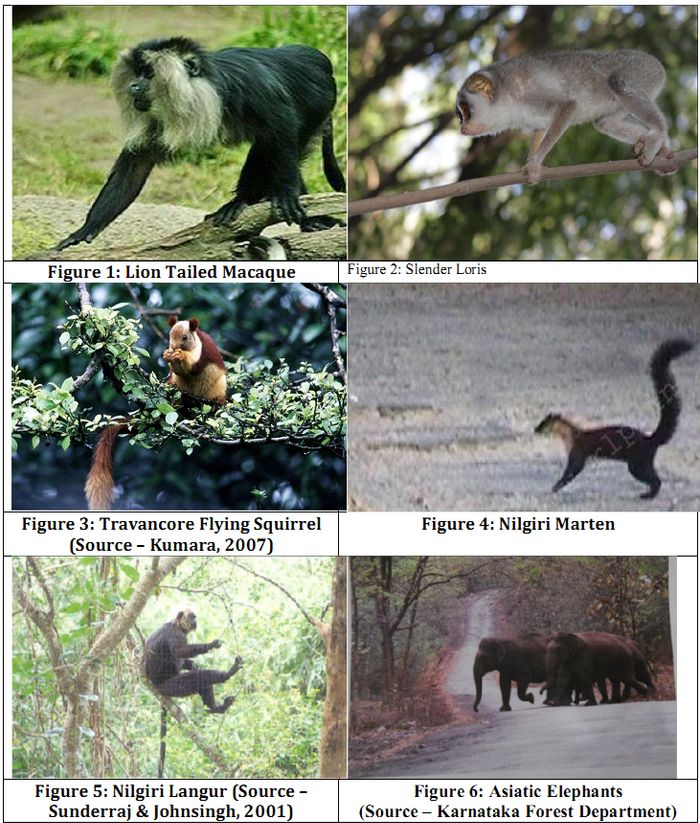

MAMMALS

The Western Ghats is endowed with the presence of many endemic and Red listed mammals like Lion-tailed macaque, Slender Loris, Nilgiri Marten, Travancore Flying Squirrel, Nilgiri Langur, Nilgiri Tahr, Elephant, Tiger, Malabar civet, etc. Many National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries have been identified to provide protection to such mammals and other faunal groups. However, they continue to face serious threats with local hunting being one of the most important threats. Hunting has existed in the Western Ghats since historical times (Chandran, 1997), while in the 19th century got accelerated and it continues to persist (Madhusudan and Karanth, 2002; Kumara and Singh, 2004a) undermining all conservation efforts. The loss of biodiversity due to hunting practices is unaccounted for and is carried out by a large number of people targeting a wide range of species.

In spite of the rich mammalian diversity in the Western Ghats, not many significant studies have been undertaken to document and study them. Some notable studies on the mammals include: mammal survey in Karnataka by Prasad et al (1978), lion-tailed macaques survey in Karnataka (Karanth, 1985; Singh et al, 2000), documentation of occurrence of large mammals in Kudremukh National Park (Karanth et al, 2001), study on distribution and abundance of primates in Western Ghats of Karnataka (Kumara and Singh, 2004), distribution and conservation of Slender Loris in Karnataka (Kumara et al, 2006), distribution and conservation status of bonnet macaques, rheus macaques and Hanuman langurs in Karnataka (Kumara et al, 2010). The presence of such important mammals signifies the ecological importance of the region.

Ali et al (2008) documented the faunal assemblages in the Myristica swamps of central Western Ghats of Uttara Kannada district. They recorded the presence of 15 mammals including the endemic and endangered Lion Tailed Macaque. The biodiversity and ecological significance of Gundia river basin in central Western Ghats (Gururaja et al 2007; Ramachandraet al 2010) highlight the occurrence of 22 different mammals in the region. This region was found to be harbouring many important and significant mammals such as Tiger, Sloth Bear, Indian Bison, Leopard, Barking Deer, Indian Mouse Deer, Asian Elephant, Wild Dog, Lion Tailed Macaque, Pangolin, Porcupine, Nilgiri Martin, Travancore Flying Squirrel, Common Flying Squirrel, Indian Civet, Palm Civet, Slender Loris.

Kumara and Singh (2006) assessed the distribution and relative abundance of giant squirrels and flying squirrels and found that two species of giant squirrels, the Indian giant squirrel and the grizzled giant squirrel and two species of flying squirrel, the large brown flying squirrel and the small Travancore flying squirrel were occurring in the state. They were distributed in the forests of both Eastern and Western Ghats but they were confined to the forests the Indian giant squirrels and large brown flying squirrels were found to be occurring in both deciduous and evergreen forests while the small Travancore flying squirrels were occupying high rainfall evergreen forests and the grizzled giant squirrels occupied the riverine forests. Hunting was found to be a major threat influencing the abundance of all the species except the grizzled giant squirrel.

Bali et al (2007) hypothesized that the mammalian communities in the coffee plantations can be taken as a function of their proximity to the protected area and vegetation characteristics. They sampled the vegetation and mammals of the coffee landscape around the moist deciduous forests of Bhadra Wildlife Sanctuary in Chikmagalur district. A total of 93 tree species and at least 28 mammal species were recorded in this study. They also observed that the estates near to the Bhadra WLS had more species than the estates far away and the overall mammal species richness in an estate was negatively correlated with its distance from the Bhadra WLS. The local vegetation characteristics were found to be influencing the abundance of some small species.

Kumara et al (2010) carried out a study to assess the population of bonnet macaques, rheus macaques and Hanuman langurs in the areas outside notified wildlife reserves in the state of Karnataka. They travelled throughout the 26 districts of the state conducting vehicular surveys and recorded the data regarding the presence or absence of the groups of the primates and compared the data with earlier records. No sightings were made and no information could be collected on the occurrence of rheus macaques in the state whereas the bonnet macaques were recorded from throughout the state except for few districts with a mean encounter rate of 2.10 groups/100 km. In the case of Hanuman langurs, a total of 139 groups were sighted with an encounter rate of 1.43 groups/ 100 km. Hence, they found that the bonnet macaques and Hanuman langurs are distributed throughout the state, however, their encounter rates differed significantly across the biogeographic zones. They emphasized that periodic assessment of the conservation status of such primates should take place and appropriate conservation measures should be undertaken to prevent them from becoming endangered. Some faunal species which are highly endemic and featuring in the IUCN Red list are found to be occurring in good numbers in the central Western Ghats of Karnataka state emphasizing the ecological importance of this region. However, there is an urgent need for developing suitable conservation strategies for such endangered and threatened fauna before they vanish out from the ecosystem. The details of some of such important species are mentioned here:

Lion Tailed Macaque - Macaca silenus, commonly known as Lion-tailed macaque, is

categorized as Endangered by the IUCN Red List and is endemic to the rainforests of the

Western Ghats. This belongs to the Scheduled I of protected animals according to the Wild

life protection act 1972. Habitat loss and fragmentation has seriously affected this species

(Karanth, 1992) and its population has declined drastically with its becoming local extinct in

some areas. Karanth (1992) has emphasized the importance of lion-tailed macaques as

flagship species for the rapidly declining rainforests of this biodiversity hotspot. Karanth

(1985) had reported the presence of 4, 1, 6 and 2 groups of lion-tailed macaques in

Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, Subrahmanya Reserve forests

and Sakaleshpur reserve forests. Whereas, Kumara & Sinha (2009) reported the presence of

just two groups lion-tailed macaques in Pushpagiri - Subrahmanya region having four and

five individuals respectively. Their study shows an overall decline of 69% in the groups of

same study areas surveyed by Karanth (1985). Various surveys have been carried out on the

occurrence of LTM in various parts of South India and hence it has been found that they

occur in Sringeri forest range (Singh et al. 2000); Brahmagiri-Makut and Sirsi-Honnavara

areas (Kumara and Singh 2004a); the Kudremukh National Park, Someshwara Wildlife

Sanctuary, and Mookambika Wildlife Sanctuary (Vasudevan et al. 2006); and the Talakaveri

Wildlife Sanctuary, Pushpagiri-Subramanya including Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary, and

Sharavathi- Gersoppa including Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (Kumara 2007).

However, the shrinkage and fragmentation of habitat have resulted in sharp decline in lion-tailed macaque populations across the state and thus, they emphasize the need to investigate

more areas having these macaque populations and develop conservation strategies for their

protection. If this is not done, these macaques may have to face extinction.

Slender Loris - Slender lorises in India have two sub-species namely Loris lydekkerianus lydekerrianus which prefers drier form of habitat and other Loris lydekkerianus malabaricus which prefers the wet form of habitat. L. lydekkerianus malabaricus is commonly known as Malabar Slender Loris and is found in the rainforest of Western Ghats (Kumar et.al. 2006). Slender lorises are small, often solitary and nocturnal. The Slender Loris of India are assigned to the category of Near Threatened by IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and have been assigned highest level of prtion under Schedule I, of Indian Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. Kumara et al (2006) recorded the presence of Loris lydekkerianus malabaricus in Uttara Kannada, Shimoga, Hassan, Chikmagalur and Dakshin Kannada districts.

Travancore Flying Squirrel - Petinomys fuscocapillus, commonly known as Travancore Flying squirrel, is one of the small flying squirrel and is expected to be present in some parts of the Western Ghats. This belongs to the Scheduled I of protected animals according to the Wild life protection act 1972. This species was rediscovered from Kerala after a gap of 70 years by Kurup (1989) and after a couple of years it was reported from Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary in Tamil Nadu by Umapathy (1998). However, there were no sight records of this squirrel from Karnataka state until Kumara & Singh (2005a) reported it from Makut Reserve forests and later Kumara (2007) reported it from Pushpagiri Wildlife Sanctuary and Shravathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. All the sightings were from western foot hills and slopes of Western Ghats, having high rainfall and humidity. This species has been accredited as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List and requires more study and conservation strategies.

Nilgiri Marten - Martes gwatkinsii, commonly known as the Nilgiri marten is one of the largest and rarest Indian mustelids and is endemic to the Western Ghats. Mudappa (1999) has reported that it prefers moist and tropical rainforests with an altitude of 300 - 1200 m as its habitat. The marten is legally protected under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 (schedule II), is listed on Appendix-III of the Convention of Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and is categorized as Vulnerable by IUCN Red List. However, habitat destruction, fragmentation and hunting of Nilgiri marten are hurdles in its conservation. The presence of Nilgiri marten has been reported in Brahmagiri Wildlife Sanctuary by Schreiber et al in 1989.