| Sahyadri Conservation Series: 8 |

ENVIS Technical Report: 37, January 2012 |

|

Anuran Diversity and Distribution in Dandeli Anshi Tiger Reserve |

|

|

|

Introduction

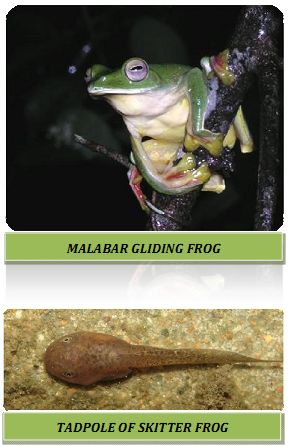

What are Amphibians?

Amphibians include frogs, toads, salamander and caecilians, are the first tetrapod vertebrates dwell on land. They evolved from the bony fishes nearly 360 million years ago (in the late Devonian period). The early amphibian fossil records are from Madagascar Island. Amphibians got their name because they possess two life stages (in Greek, amphi-dual and bios-life form), one as tadpoles and other as adults. In general, tadpoles live in water and feed on algae, while adults (frog or toad) dwell on land or water and feed on insects. One can find amphibians in almost all the continents (except Antarctica). They are found in many habitats and microhabitats ranging from human habitations to desert regions. They are found inside the water, muddy and rock crevices, burrowing deep in the soil, or bushes, high canopy trees, etc. Rainy season are the best time to find amphibians. As rains provide adequate moisture to keep eggs from drying, many of the amphibians breed during this period having maximum chance of survival of their eggs. Generally, amphibians are active during night (nocturnal) and one can easily locate and identify the amphibian species based on their calls in the night hours. Amphibians include frogs, toads, salamander and caecilians, are the first tetrapod vertebrates dwell on land. They evolved from the bony fishes nearly 360 million years ago (in the late Devonian period). The early amphibian fossil records are from Madagascar Island. Amphibians got their name because they possess two life stages (in Greek, amphi-dual and bios-life form), one as tadpoles and other as adults. In general, tadpoles live in water and feed on algae, while adults (frog or toad) dwell on land or water and feed on insects. One can find amphibians in almost all the continents (except Antarctica). They are found in many habitats and microhabitats ranging from human habitations to desert regions. They are found inside the water, muddy and rock crevices, burrowing deep in the soil, or bushes, high canopy trees, etc. Rainy season are the best time to find amphibians. As rains provide adequate moisture to keep eggs from drying, many of the amphibians breed during this period having maximum chance of survival of their eggs. Generally, amphibians are active during night (nocturnal) and one can easily locate and identify the amphibian species based on their calls in the night hours.

Amphibian Systematics: Present Scenario in the Western Ghats

All living and described amphibians are divided into three groups, namely, gymnophiona (caecilians and ichthyophis), caudata (salamanders and newts) and anura (frogs and toads). There are over 6,771 species of amphibians world over, of which India harbours about 337 species (Anil et al., 2011a, 2011b; Biju et al., 2011; Dinesh et al., 2011). Species belonging to all three extant orders are recorded in India. The species distribution across India is not uniform, attributed mainly to the prevailing climate, phenology and topography (zoogeography) associated with habitat preferences of the species. Nearly 60% of the India amphibians are endemic to three important hotspots of biodiversity, namely, the Western Ghats, the north-eastern Himalaya and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The Western Ghats are 1600km long mountainous terrain from Kanyakumari to river Tapti (8°N to 21°N) along the West coast of India having an average width of about 100km, forms a key amphibian hotspot. Of the 180 species available from the Western Ghats (Dinesh and Radhakrishnan, 2001 and personal compilation), 160 species are described from the region. In the last decade, 80 new species are described from the region. This supports the estimation of Aravind et al., (2004) and Gower et al., (2004) of more species to be described from the Western Ghats. Among the described species, 87.8% (158 species) are endemic to the region.

Despite being rich in amphibians and their endemism, the Western Ghats still lack comprehensive list of amphibians available from the region, again due to the skewed availability of research output from Southern and Northern Western Ghats. Research on species distribution in the Western Ghats are limited to few studies, more scanty are on the protected areas (Inger et al., 1984a, b; 1987; Daniels, 1992; Krishnamurthy, 2003; Naniwadekar and Vasudevan, 2007; Sameer Ali et al., 2007).

There are several Protected Areas in the Western Ghats of Karnataka (for details please refer Sameer Ali et al., 2007), but systematic amphibian research are carried out only in Kudremukh National Park (Krishnamurthy, 2003; Vasudevan et al., 2006) and Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary (Sameer Ali et al., 2007). This is quite evident for Protected Areas of rest of the Western Ghats also (Kalakkad Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Vasudevan et al., 2001; Naniwadekar and Vasudevan, 2007; Ponmudi, Inger et al., 1984a, b; 1987). Das et al., (2006) stress that amphibians are poorly represented from Protected Areas of the Western Ghats.

This study was carried out in Dandeli Anshi Tiger Reserve to address the aforesaid issues in a systematic and scientific manner, so as to provide baseline information on amphibians of the region from Western Ghats and more specifically from a Protect Area.

Why study amphibians?

Amphibians inhabit two different habitats (water and land) during their life cycle.For surviving in two diverse habitats, they have unique adaptations to thrive well in these habitats. In their early life stage, amphibians are fish like (called tadpoles) with streamlined body (without scales), breath through gills and feed with labial palp (keratinized lips) on algae. Later on, they get retrogressively metamorphosed to adult frog/toad, where in the body completely loses fish like appearance. It now possesses lungs to respire, hands and legs to move, and frontally attached tongue and bony mouthparts to catch insects. In addition, amphibians also breathe through their skin. Generally, amphibians have relatively wide distribution, bimodal life style, ectothermic conditions with stable environmental temperature of 20-30°C and moist permeable skin. All these have made them highly sensitive and susceptible to the external changes. Hence amphibians are regarded as the best ecological indicators among the vertebrates.

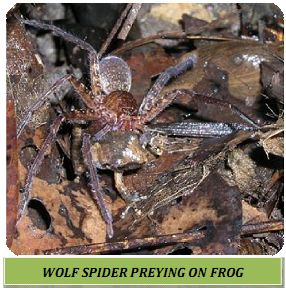

In the ecosystem, amphibians function both as prey and predator, and they constitute a vital component of the ecosystem. In ecosystem management, they are the best biological pest controllers. Amphibians are part of human culture (folk stories, frog marriages to get rain, Rig Vedic verses, etc) and food delicacy. In science education they have immense value as model specimen to understand anatomy and histology. Anti-microbial peptides are unique group of chemicals available in amphibian skin with very high therapeutic values in developing anti bacterial and anti fungal medicines. In the ecosystem, amphibians function both as prey and predator, and they constitute a vital component of the ecosystem. In ecosystem management, they are the best biological pest controllers. Amphibians are part of human culture (folk stories, frog marriages to get rain, Rig Vedic verses, etc) and food delicacy. In science education they have immense value as model specimen to understand anatomy and histology. Anti-microbial peptides are unique group of chemicals available in amphibian skin with very high therapeutic values in developing anti bacterial and anti fungal medicines.

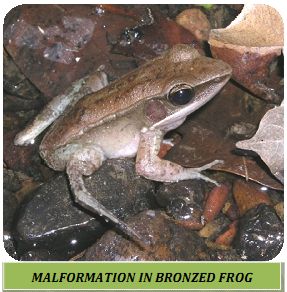

Over the last two decades, the amphibians are exhibiting decline in their population throughout the world as an indication of increased degradation, deterioration and alteration of habitat/microhabitat and changes in global climate (evidenced by increased UV-B radiation) due to anthropogenic activities. Land use and land cover changes coupled with indiscriminate usage of pesticide and fertilizers are the main drivers of habitat deterioration. Diseases, road kills and culling for trade (illegal smuggling) have also reduced the amphibian population. Amphibian decline has been considered as an early warning to human welfare in the future.

In tropics, diversity of amphibians are exceptionally high at the same time, these regions are prevailing under tremendous pressure from anthropogenic and anthropocentric activities. The amphibian declines in this region are sudden, selective and more pronounced that has necessitated the evolving of strategies for conservation and restoration of amphibians and their habitats. Monitoring anuran diversity and their distribution would provide an insight into the prevailing conditions of an ecosystem and its health. Such monitoring and documentation are important towards assessment and conservation of biodiversity of a region, which in turn helps in prioritizing the region for immediate conservation and management action. In tropics, diversity of amphibians are exceptionally high at the same time, these regions are prevailing under tremendous pressure from anthropogenic and anthropocentric activities. The amphibian declines in this region are sudden, selective and more pronounced that has necessitated the evolving of strategies for conservation and restoration of amphibians and their habitats. Monitoring anuran diversity and their distribution would provide an insight into the prevailing conditions of an ecosystem and its health. Such monitoring and documentation are important towards assessment and conservation of biodiversity of a region, which in turn helps in prioritizing the region for immediate conservation and management action.

Captive breeding, ex-situ conservation practices like putting them in artificial amphibian parks are not effective for amphibian conservation. Catchment based conservation plans with holistic approaches are more suitable for amphibian conservation. This requires information on vital habitat variables such as humidity, temperature, vegetation, etc., of individual species. A well planned systematic study would provide such necessary information, ultimately helping in proper conservation measures for amphibians. Continuous monitoring and creating awareness in public and especially in the young minds will certainly help in effective conservation of amphibians (Gururaja, 2004).

|

|

|

Dr. T.V. Ramachandra

Centre for Sustainable Technologies,

Centre for infrastructure, Sustainable Transportation and Urban Planning (CiSTUP),

Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560 012, INDIA.

E-mail : cestvr@ces.iisc.ac.in

Tel: 91-080-22933099/23600985,

Fax: 91-080-23601428/23600085

Web: http://ces.iisc.ac.in/energy

Gururaja K VEnergy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore – 560 012, INDIA.

E-mail:

gururaj@ces.iisc.ac.in

Citation: Gururaja KV and Ramachandra TV, 2012. Anuran Diversity and Distribution in Dandeli Anshi Tiger Reserve., ENVIS Technical Report : 37, Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012.

Anil, Z., Dinesh, K.P., Kunhikrishnan, E., Das, S., David V. Raju and Radhakrishnan, C. 2011a. Nine new species of frogs of the genus Raorchestes (Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from southern Western Ghats, India. Biosystematica, 5(1): 25-48.

Anil, Z., Dinesh, K.P., Radhakrishnan, C.,Kunhikrishnan, E., Palot, M.J. and Vishnudas, C.K. 2011b. A new species of Polypedates Tschudi (Amphibia: Anura: Rhacophoridae) from southern Western Ghats, Kerala, India. Biosystematica, 5(1): 49-53.

Biju, S.D., Bocxlaer, I.V., Mahony, S., Dinesh, K.P., Radhakrishnan, C., Anil, Z., Giri, V. and Bossuyt. F. 2011. A taxonomic review of the Night Frog genus Nyctibatrachus Boulenger, 1882 in the Western Ghats, India (Anura: Nyctibatrachidae) with description of twelve new species. Zootaxa, 3029:1-96

Dinesh, K.P. and Radhakrishnan, C. 2011. Checklist of amphibians of Western Ghats.Frogleg, 16: 15-20.

Aravind, N. A., Ganeshaiah, K.N. and Uma Shaanker, R.2004. Croak, croak, croak: Are there more frogs to be discovered in Western Ghats? Current Science, 86: 1471-1472.

Gower, D. J., Bhatta, G., Giri, V., Oommen, O. V., Ravichandran, M. S. and Wilkinson, M. 2004. Biodiversity in the Western Ghats: the discovery of new species of caecilian amphibians. Current Science 87: 739-740.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1984a.A report on a collection of amphibians and reptiles from the Ponmudi, Kerala, South India.Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 81: 406-427.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1984b.A report on a collection of amphibians and reptiles from the Ponmudi, Kerala, South India.Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 81: 551-570.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1987.Ecological structure of a herpetological assemblage in South India.Amphibia-Reptilia, 8: 189-202.

Daniels, R.J.R. 1992. Geographical distribution patterns of amphibians in the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Biogeography, 19:521-529.

Krishnamurthy, S.V. 2003. Amphibian assemblages in undisturbed and disturbed areas of Kudremukh National Park, central Western Ghats, India. Environmental Conservation, 30: 274-282 doi:10.1017/S0376892903000274

Naniwadekar, R. and Vasudevan, K. 2007. Patterns in diversity of anurans along an elevational gradient in the Western Ghats, South India.Journal of Biogeography, 34, 842–853.

Sameer Ali, Rao, G.R., Divakar K. Mesta., Sreekantha, Vishnu D.Mukri, SubashChandran, M.D., Gururaja, K.V., Joshi, N.V. and Ramachandra, T.V. 2007. Ecological Status of Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. Prism Books Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore.

Sameer Ali, Rao, G.R., Divakar K. Mesta., Sreekantha, Vishnu D.Mukri, SubashChandran, M.D., Gururaja, K.V., Joshi, N.V. and Ramachandra, T.V. 2007. Ecological Status of Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. Prism Books Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore.

Krishnamurthy, S.V. 2003.Amphibian assemblages in undisturbed and disturbed areas of Kudremukh National Park, central Western Ghats, India. Environmental Conservation, 30: 274-282 doi:10.1017/S0376892903000274

Vasudevan, K., Singh, M.,Singh, V.R., Chaitra, M.S., Naniwadekar, R.S., Deepak,V. and Swapna,N. 2006. Survey of biological diversity in Kudremukh Forest Complex.Karnataka Forest Department report, 60 p.

Sameer Ali, Rao, G.R., Divakar K. Mesta., Sreekantha, Vishnu D.Mukri, SubashChandran, M.D., Gururaja, K.V., Joshi, N.V. and Ramachandra, T.V. 2007. Ecological Status of Sharavathi Valley Wildlife Sanctuary. Prism Books Pvt. Ltd., Bangalore.

Vasudevan, K., Kumar, A., and Chellam, R. 2001. Structure and composition of rainforest floor amphibian communities in Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve. Current Science 80(3): 406-412.

Naniwadekar, R. and Vasudevan, K. 2007. Patterns in diversity of anurans along an elevational gradient in the Western Ghats, South India.Journal of Biogeography, 34, 842–853.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1984a.A report on a collection of amphibians and reptiles from the Ponmudi, Kerala, South India.Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 81: 406-427.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1984b.A report on a collection of amphibians and reptiles from the Ponmudi, Kerala, South India.Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 81: 551-570.

Inger, R.F., Shaffer, H.B., Koshy, M. and Bakde, R. 1987.Ecological structure of a herpetological assemblage in South India.Amphibia-Reptilia, 8: 189-202.

Das, A., Krishnaswamy, J., Bawa,K.S., Kiran, M.C., Srinivas, V., Kumar, N.S. and Karanth, K.U. 2006. Prioritisation of conservation areas in the Western Ghats, India.Biological Conservation, 133(2006): 16-31.