|

Appraisal of Forest Ecosystems Goods and Services: Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation |

|

T. V.Ramachandra1, 2, 3, Divya Soman1 Ashwath D. Naik1 M. D. Subash Chandran1

1Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES)

2 Centre for Sustainable Technologies (ASTRA)

3Centre for infrastructure, Sustainable Transportation and Urban Planning (CiSTUP) Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012, Karnataka, India

Telephone: 91-80-23600985, 22932506, 22933099, Fax: 91-80-23601428, 23600085, 23600683

*Corresponding Author: tvr@iisc.ac.in,energy.ces@iisc.ac.in

|

Introduction

An ecosystem is a complex of interconnected living organisms inhabiting a particular area or unit space, together with their environment and all their interrelationships and relationships with the environment having well-maintained ecological processes and interactions (Ramachandra et al. 2007, 2015). Ecosystem functions include the exchange of energy between the plants and animals that are needed for the sustenance of life. These functions include nutrient cycling, oxygen regulation, water supply etc. The flow of goods or services which occur naturally by ecological interactions between biotic and abiotic components in an ecosystem is often referred as ecosystem goods and services. These good and services not only provide tangible and intangible benefits to human community, but also are critical to the functioning of ecosystem. Thus, ecosystem goods and services are the process through which natural ecosystems and the species that make up sustain and fulfill the human needs (Newcome et al. 2005). Ecosystems are thus natural capital assets supporting and supplying services highly valuable to human livelihoods and providing various goods and services (MEA 2003; Daily and Matson 2008; Gunderson et al. 2016). The tropical forests are the rich source of biodiversity and are probably thought of containing more than half of world’s biodiversity. Biodiversity is important to human kind in fulfilling its needs by way of providing food (80,000 species), medicine (20,000 species), drug formulations (8,000 species) and raw materials (90% from forests) for industries (Ramachandra et al. 2016a, b; Ramachandra and Nagarathna 2001: Ramachandra and Ganapathy 2007). Among the terrestrial biomes, forests occupy about 31 percent (4,033 million hectare) of the world’s total land area and of which 93 percent of the world’s forest cover is natural forest and 7 percent is planted (FAO 2010; TEEB 2010; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016). Forest ecosystems account for over two-thirds of net primary production on land – the conversion of solar energy into biomass through photosynthesis, making them a key component of the global carbon cycle and climate (MEA 2003). The forests of the world harbor very large and complex biological species diversity, which is an indicator for biological diversity and the species richness increases as we move from the poles to the equatorial region. Forest ecosystem services can provide both direct and indirect economic benefits. India’s forest has been classified into four major groups, namely, tropical, sub-tropical, temperate, and alpine(Champion and Seth 1968). Tropical forest in particular contributes more than the other terrestrial biomes to climate relevant cycles and biodiversity related processes. These forests constitute the earth’s major genetic reservoir and global water cycles (Anderson and Bojo 1992; Gunderson et al. 2016).

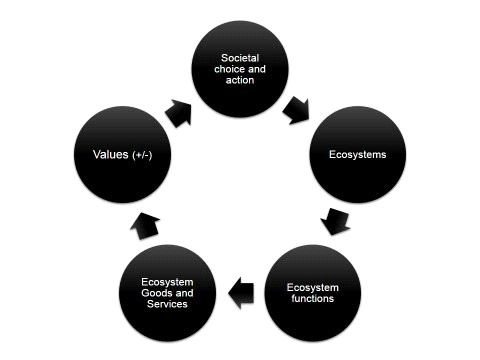

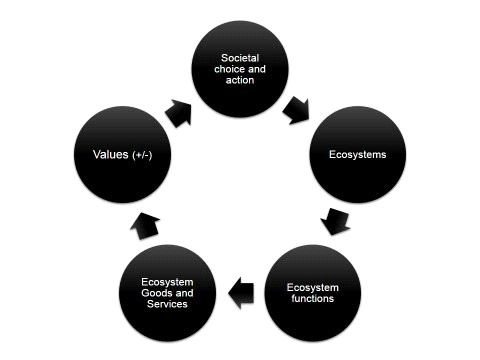

The ecosystem provides various fundamentalbenefits for our survival such as food; soil production, erosion and control; climate regulation; water purification; bioenergy, etc. These benefits and services are very crucial for the survival of humans and other organisms on the earth (MEA 2003; de Groot et al. 2002; VillegasPalacio et al. 2016). It includes provisioning services such as food and water, regulating services such as flood and disease control, cultural services such as spiritual, recreational and cultural benefits, and supporting services such as nutrient cycling that maintains the conditions for life on earth. Sustainable ecosystem service delivery depends on the health, integrity and resilience of the ecosystem. Policy-makers, interest groups and the public require reliable information on the environmental, social and economic value of regulating services to make informed decisions on optimum use and on the conservation of ecosystems (Kumar et al. 2010). The prime reason for ecosystem mismanagement is the failure to realise the value of ecosystem. Valuation of ecosystem is essential to respite human activities apart from accounting their services in the regional planning (Ramachandra et al. 2011). The range of benefits derived from ecosystem can be direct or indirect, tangible or intangible, can be provided locally or at global scale – all of which makes measurement particularly hard (TEEB 2010). Economic valuation of natural resources aids the social planners to design and better manage the ecosystems and related human wellbeing. Figure 1 shows the interrelationship of ecosystem, ecosystem functions, economic values and its impact on ecosystem through incentive/disincentive.

Fig. 1. Ecosystems heal th and economi c values

Valuation of ecosystems enhances the ability of decision-makers to evaluate trade-offs between alternative ecosystem management regimes and courses of social action that alter the use of ecosystems and the multiple services they provide (MEA 2003; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016).

Fig. 1. Ecosystems heal th and economi c values

Valuation of ecosystems enhances the ability of decision-makers to evaluate trade-offs between alternative ecosystem management regimes and courses of social action that alter the use of ecosystems and the multiple services they provide (MEA 2003; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016).

Valuation reveal the relative importance of different ecosystem services, especially those not traded in conventional markets (TEEB 2010).The ecosystem goods and services are grouped into four categories as provisioning, regulating, supporting and information services (MEA 2003; de Groot et al. 2002), based on the Total Economic Value (TEV) framework with significant emphasis on intrinsic aspects of ecosystem value, particularly in relation to socio-cultural values (MEA 2003). TEEB (2010) excludes the supporting services(such as nutrient cycling and food-chain dynamic) and incorporates habitat service as a separate category.

Integrated framework for assessing the ecosystem goods and services (TEEB 2010; de Groot et al. 2002; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016) involves the translation of complex structures and processes into a limited number of ecosystem functions namely production, regulation, habitat and information. These goods and services are valued by humans and grouped as ecological, socio-cultural and economic values. All values are estimated using the common metric, which helps in aggregating values of different goods and services (DEFRA 2007). When the market does not capture the value of environmental goods or services, techniques associated with ‘shadow pricing’ or ‘proxy price’ are used to indirectly estimate its value. Estimation of the economic values for 17 different ecosystem services (Costanza et al.1997; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016) highlight that the annual value of the ecosystem services of the terrestrial and aquatic biomes of the world to be 1.8 times higher than the global gross national product (GNP). About 63 percent of the estimated values of ecosystem services were found to be contributed by the marine ecosystems while, about 38 percent of the estimated values were found to be contributed by the terrestrial ecosystems, mainly from the forests and wetlands.

Forests, particularly tropical forests, contribute more than other terrestrial biomes to climate relevant cycles and processes and also to biodiversity related processes (Nasi et al. 2002). Forest ecosystem services with great economic value (Ramachandra et al. 2011, 2016b; Costanza et al. 1997; Pearce et al. 2002), are known to be critically important habitats in terms of the biological diversity and ecological functions. These ecosystems serve as a central component of Earth’s biogeochemical systems and are a source of ecosystem services essential for human wellbeing (Gonzalez et al. 2005; Villegas-Palacio et al. 2016). These ecosystem provides a large number of valuable products such as timber, firewood, non-timber forest product, biodiversity, genetic resources, medicinal plants, etc. The forest trees are felled on a large scale for using their wood as timber and firewood. According to FAO (2010) wood removals valued just over US$100 billion annually in the period 2003–2007, mainly accounted by industrial round wood. Further, 11 percent of world energy consumption comes from biomass, mainly fuel wood (CBD 2001). 19 percent of China’s primary energy consumption comes from biomass and 42 percent in India. Non-commercial sources of energy (such as fire wood, agricultural and horticultural residues, and animal residues) contribute about 54 percent of the total energy in Karnataka (Ramachandra et al. 2000).

Timber and carbon wealth assessment in the forests of India (Atkinson and Gundimeda 2006) show the opening stock of forest resources as 4,740,858,000 cubic meters and about 639,600 sq. km of forest area. Biomass density/ha in Indian forests is about 92 t/ha and carbon values of Indian forests is 2933.8 million tones assessed considering a carbon content of 0.5 Mg C per Mg oven dry biomass (Haripriya 2002). The closing stock of the timber is 4704 million cum and the estimate of value is Rs. 9454 billion, the stock of the carbon is 2872 million tons with a value estimate of Rs.1811 billion. Apart from serving as a storehouse of wood which is used for various purposes, there are also equally important non-wood products that are obtained from the forests. The botanical and other natural products, other than timber extracted from the forest system are referred to as non-timber forest products (NTFPs). These resources/products have been extracted from the forest ecosystems and are being utilized within the household or marketed or have social, cultural or religious significance (Falconer and Koppell 1990; Schaafsma et al. 2014; Pittini 2011). NTFP is a significant component due to its important bearing on rural livelihoods and subsistence. NTFPs are also referred ‘minor forest produce’ as most of NTFP are consumed by local populations, and are not marketed (Arnold and Pérez 2001). These include plants and plant materials used for food, fuel and fodder, medicine, cottage and wrapping materials, biochemical, animals, birds, reptiles and fishes, for food and feather. Unlike timberbased products, these products come from variety of sources like: fruits and vegetables to eat, leaves and twigs for decoration, flowers for various purposes, herbal medicines from different plant parts, wood carvings and decorations, etc. The values of NTFPs are of critical importance as a source of income and employment for rural people living around the forest regions, especially during lean seasons of agricultural crops. NTFPs provide 40-63 percent of the total annual income of the people residing in rural areas of Madhya Pradesh (Tewari and Campbell 1996) and accounted 20-35 percent of the household incomes in West Bengal. The net present value (NPV) of the forest for sustainable fruit and latex production is estimated at US$6,330/ha considering the net revenue from a single year’s harvest of fruit and latex production as US$422/hain Mishana, Rio Nanay, Peru (Peters et al. 1989) assumption of availability in perpetuity, constant real prices and a discount rate of 5 percent.

Evaluation of the direct use benefits to rural communities’ from harvesting NTFPs and using forest areas for agriculture and residential space, near the Mantadia National Park, in Madagascar (Kramer et al. 1995) through contingency valuation (CV) show an aggregate net present value for the affected population (about 3,400 people) of US$673,000 with an annual mean value per household of USD 108.

Estimation of the quantity of the NTFPs collected by the locals and forest department based on a questionnaire based survey in 21 villages of four different forest zones in Uttara Kannada district (Murthy et al. 2005), indicate the collection of 59 different plant species in the evergreen forests, 40 different plant species in the semi-evergreen forests, 12 different plant species in moist deciduous and 15 different plant species in dry deciduous forests and about 42– 80 NTFP species of medicinal importance are marketed in herbal shops. Valuation reveal an annual income per household depending on the goods availability ranges from Rs. 3,445 (evergreen forests), 3,080 (moist deciduous), 1,438 (semi-evergreen) to Rs. 1,233 (dry deciduous).

Assessment of the marketing potential of different value added products from Artocarpus sp. in Uttara Kannada district based on field surveys and the discussions with the local people and industries (Ramana and Patil 2008), revealed that Artocarpus integrifolia collected from nearby forest area and home gardens is most extensively used for preparing items like chips, papad, sweets, etc. Chips and papads are commercially produced and sold in the markets, and primary collectors get 25 percent and the processing industry get 50 percent of the total amount paid by the consumers.

Forest ecosystems also provide other indirect benefits like ground water recharge, soil retention, gas regulation, waste treatment, pollination, refugium function, nursery function etc. in addition to the direct benefits (de Groot et al. 2002). Forest vegetation aids in the percolation and recharging of groundwater sources while allowing moderate run off. Gas regulation functions include general maintenance of habits through the maintenance of clean air, prevention of diseases (for example, skin cancer), etc.

Forests act as carbon sinks by taking carbon during photosynthesis and synthesis of organic compounds, which aids in maintaining CO 2 /O2 balance, ozone layer and also sulphur dioxide balance. Carbon sequestration potential of 131t of carbon per hectare with the above ground biomass of 349 ton/ha has been estimated in the relic forest of Uttara Kannada (Chandran et al. 2010) and 11.8 metric ton (1995) in forests in India (Lal an Singh 2000) with the carbon uptake potential of 55.48 Mt (2020) and 73.48 Mt (2045) respectively (projected the total carbon uptake for the year 2020 and 2045). The carbon sequestration potential was found to be 4.1 and 9.8 Gt by 2020 and 2045 respectively.

Vegetative structure of forests through its storage capacity and surface resistance plays a vital role in the disturbance regulation by altering potentially catastrophic effects of storms, floods and droughts. Soil retention occurs by the presence of the vegetation cover which holds the soil and prevents the loss of top soil. Pollination is an important ecological service provided by the forest ecosystem and the studies have revealed that forest dwelling pollinators (such as bees) make significant contribution to the agricultural production of a broad range of crops, in particular fruits, vegetables, fiber crops and nuts (Costanza et al. 1997).

Forest also helps in aesthetic benefit, recreational benefit, science and education, spiritual benefits, etc. The scenic beauty of forests provides aesthetic and recreational benefits through psychological relief to the visitors. An investigation of cultural services of the forest of Uttaranchal (Djafar 2006) considering six services namely aesthetic, recreational, cultural heritage and identity, inspirational, spiritual and religious and educational function, highlight the recreational value of forests US$ 0.82/ha/yr for villager’s per visit. Aesthetic value derived by the preference of the villagers was estimated as US$ 7-1760 /ha/yr, derived by the preference of the villagers to live in the sites where there is good scenery. Cultural heritage and identity value was estimated as USD 1-25/ha/yr based on 24 places, 43 plant species and 16 animal species. Spiritual and religious areas was about USD 1-25/ ha/yr. Educational value was obtained from the research activity and value was similar to spiritual and religious values.

Ecotourism benefit of the domestic visitor using the travel cost method in the Periyar tiger reserve in Kerala is Rs. 161.3 per visitor (Manoharan 1996), with average consumer surplus at Rs. 9.89 per domestic visitor and Rs. 140 for foreign tourists. The value of eco-tourism (as per 2005) is extrapolated as Rs. 84.5 million. The recreational value assessment of Vazhachal and Athirappily of Kerala (Anitha and Muraleedharan 2006) reveal that visitor flow on an average is 2.3 lakh (at Vazhachal) and 5.3 lakh (Athirappily) visitors/year and the average fee collection ranges from Rs. 10 (Vazhachal) to Rs.23.5 (Athirappily) lakh / year. Parking fee for vehicles itself is about Rs. 1.39 (Vazhachal) lakh /year and Rs. 2.7 (Athirappily) lakh/ year. About Rs. 5.6 lakh is earned from visitors entrance fee and parking charges. The estimated aggregate recreation surplus of the sample is equal to Rs 20, 69,214 with an average recreation surplus per visitor of Rs. 2,593.

Recreational value in the protected site of Western Ghats (Mohandas and Rema Devi 2011) based on the relationship between travel cost and visitation rate and the willingness to pay is Rs. 26.7 per visitor and the average consumer surplus per visit is Rs. 290. A similar study carried out in the valley of a national park show the net recreational benefit as Rs. 5,88,332 and the average consumer surplus as Rs. 194.68 (Gera et al. 2008). The total recreation value of Dandeli wildlife sanctuary using travel cost method during 2004-05 shows the total recreation value of Rs. 37,142.86 per Sq. km with the total value of Rs. 1,76,43,600 (Panchamukhi et al. 2008). Similarly, based on the willingness to pay for the preservation of watershed in Karnataka indicate a value of Rs.125.45 per hectare and the total value of Rs. 480 million (for 2004-05).

Valuation of forest in Uttarakhand, Himalayas using the benefit transfer method (Verma et al. 2007) shows a total economic value of Uttrakhand forests as Rs. 16,192 billion, accounting Rs. 19,035 million from the direct benefits (including tourism) and Rs. 173,120 million from the indirect benefits and silt control service is accounted as Rs. 2062.2 million. Carbon sequestration is accounted as Rs.2974 million at US $ 10 per t of C considering the net accumulation of 6.6 Mt C per year in biomass. Aesthetic beauty of the landscape is estimated as 10,665.3 million and pollination service value is accounted to be Rs. 25,610 million/yr. Natural ecosystems also provide unlimited opportunities for environmental education and function as field laboratories for scientific research (de Groot et al. 2002).

Sacred groves present in varied ecosystems viz., evergreen and deciduous forests, hill tops, valleys, mangroves, swamps and even in agricultural fields in Uttara Kannada district represent varied vegetation and animal profiles (Ray et al. 2011, 2015). The protection of patches of forest as sacred groves and of several tree species as sacred trees leads to the spiritual function provided by the forest (Chandran 1993). Sacred groves also play an important role in the cultural service provided by the forest. The groves do not fetch any produce which can be used for direct consumptive or commercial purpose. Creation of hypothetical market fetches price worth Rs. 600/quintal for a woody species and Rs. 40/quintal for non-wood product. The value of sacred grove assessed through willingness to pay to preserve the sacred grove in Siddapur taluk of Uttara Kannada district (Panchamukhi et al. 2008), show the value of Rs. 7280/ per hectare.

The major threat to the forests today is deforestation caused by several reasons such as rise in the population, exploitation activities which include expansion of agriculture land, ranching, wood extraction, development of infrastructure. Shifting cultivation is considered to be one of the most important causes of deforestation (Myers 1984). The loss of biodiversity is the second most important problem in nearly every terrestrial ecosystem on Earth. This loss is accelerating driven by the over-exploitation of natural resources, habitat destruction, fragmentation and climate change (MEA 2003). Even though the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) has adopted a target of reducing the rate of biodiversity loss at global, regional and national levels by 2010 (Mace 2005), still the loss of biodiversity is at a high pace. Nearly, 75 percent of the genetic diversity of domesticated crop plants has been lost in the past century. About 24 percent of mammals and 12 percent of bird species are currently considered to be globally threatened. Despite the essential functions of ecosystems and the consequences of their degradation, ecosystem services are undervalued by society, because of the lack of awareness of the link between natural ecosystems and the functioning of human support systems.

Objectives

Forest ecosystems are critical habitats for diverse biological diversity and perform array of ecological services that provide food, water, shelter, aesthetic beauty, etc. Valuation of the services and goods provided by the forest ecosystem would aid in the micro level policy design for the conservation and sustainable management of ecosystems. Main objective of the study is to value the forest ecosystems in Uttara Kannada forest. This involved computation of total economic value (TEV) of forest ecosysem considering provisioning, regulating, supporting and information services provided by he ecosystem.

|

|

Citation :Ramachandra T. V, Divya Soman, Ashwath D Naik, Subash Chandran M D, 2017. Appraisal of Forest Ecosystems Goods and Services: Challenges and Opportunities for Conservation, Journal of biodiversity, 8(1):61-78

|