Introduction and Methodology

Plants form an important source of traditional medicines for a major portion of population living in the tropical countries, since time immemorial. Majority of the medicinal plants in India are higher flowering plants which play a significant role in the economy of the country, providing raw materials for a variety of industries. The complex forest types in Western Ghats serve as treasure troves of about 700 medicinal plant species of which many find their applications in the traditional and folk medicine practices by the local communities (Soni, 2009). The Western Ghats, running almost parallel to the west coast of India, along with Sri-Lanka is one among 34 biodiversity hotspots of the world. It also features among the 200 globally most important eco-regions in the world (Olson and Dinerstien, 1998). Covering an area of about 160,000 km2, this rugged range of hills stretches for about 1600 km from the south Gujarat in the north to nearly the southern tip of the Indian Peninsula (8°N-20°N). The complex geography, wide variations in annual rainfall from 1000-6000 mm, and altitudinal decrease in temperature, coupled with anthropogenic factors, have produced a variety of vegetation types in the Western Ghats.

The Central Western Ghats mainly encompassing Uttara Kannada and neighbouring districts of Karnataka State has a variety of climatic conditions, soil and topography leading to different ecological and environmental regimes which support their own characteristic set of plants and animals (Ramachandra et al., 2012), and of course, medicinal plants as well. The knowledge related to the medicinal properties of various plant resources goes back to the pre-historical days. The Rigveda, the earliest Indian scripture, contains the records of the preparation and use of medicines from plants. It was followed by Atharvaveda in which the uses of the plants described were more varied and these works were followed by monumental contributions like Charaka Samhita, Sushruta Samhita and Ashhtanga Hridaya. Many rural people throughout the tropics rely on medicinal plants because of their effectiveness, lack of modern medical alternatives, and cultural preferences (Balick, et al., 1996). The indigenous forest-dwelling people are known to possess an exceptional knowledge base on medicinal plants, which range from lichens and algae to various herbs, shrubs, climbers and trees. Many species are distributed from canopy to understory in the complex evergreen forest; whereas other occur in drier forests to scrub, grasslands, rocky areas, water bodies, sea beaches, even as weeds in household gardens or in the hedges. The individual species ecology and community ecology of medicinal plant species are often complex and their proper understanding, including their medicinal properties and uses requires taxonomic, ecological and ethno-botanical knowledge, as well as updated knowledge on such species from the fields of pharmacognosy and pharmacological applications. Depletion of biodiversity at an alarming rate due to anthropogenic activities has necessitated inventorying, monitoring, conservation and management of medicinal plants in their natural habitats. Hence, vegetation and floristic studies have gained increasing importance and relevance in recent years. The current study was carried out, with financial and logistic support from the Karnataka Forest Department, Honavar Forest Division, with the objective of assessing general floristic and medicinal plants status, their diversity and regeneration status in Shirgunji and Jankadkal, two of the Medicinal Plants Conservation Areas (MPCAs) of the Division in Uttara Kannada coast.

The tropical forests of Uttara Kannada district are bestowed with richness of medicinal plants which have formed an important component of the traditional knowledge of various tribes and local communities residing in the district. Several studies have focussed on the diverse applications/uses of the medicinal plants by these communities. Bhandari et al (1995) investigated upon the uses of medicinal plants by the Siddi tribe which is mainly located in the northern part of the district. The Siddis often cured stomach acidity with the infusion of stem bark of Garcinia indica. They believe that the consumption of the stem sap of Calamus thwaitesii, coinciding with menstrual cycle, prevented conception. Harsha et al. (2002) in their studies on the ethnobotanical knowledge on the medicinal plants of the Marathi/Konkani speaking Kunabi community in the district found that the acrid juice of endemic tree Holigarna arnottiana was applied as antiseptic for fresh cuts and wounds while the bark of Mangifera indica crushed along with bark of Artocarpus heterophyllus, givenin water, was effective in treating dysentery. Harsha et al. (2003) documented the ethno-medical practices of local people residing mainly in and around the semi-evergreen to evergreen forested areas for treatment of skin diseases. They foun that plants such as Ervatamia heyneana, Naravelia zeylanica and Aristolochia indica were applied externally for the treatment of itches, boils, scabies and other skin allergies. The ethno-medico-botanical knowledge of Karivokkaliga community, living in interior forest hamlets of Uttara Kannada, was studied by Somashekhara et al. (2010). The Karivokkaligas used plants like Holarrhena pubescens for treatment of dysentery, fruit of Garcinia indica for treatment of cold, bark powder of Artocarpus heterophyllus for treatment of impotency and bark of Ervatamia heyneana for snake bite. Besides these the applications of other important medicinal plants found in the study region are found in many earlier works: oil from root, bark and leaves of Cinnamomum malabathrum for rheumatic affections as external applications; root powder of Glycosmis pentaphylla for fever; bark decoction of Diospyros candolleana for rheumatism and swellings; bark of Mimusops elengi as cooling agent, cardio-tonic, stomachic, anthelmintic, astringent and for curing biliousness, diseases of gums and teeth; fruits of Embelia ribes are used as appetizer, carminative, anthelmintic, laxative and helps in curing tumours, bronchitis, diseases of heart, jaundice and mental diseases (Kirthikar and Basu; 2003).

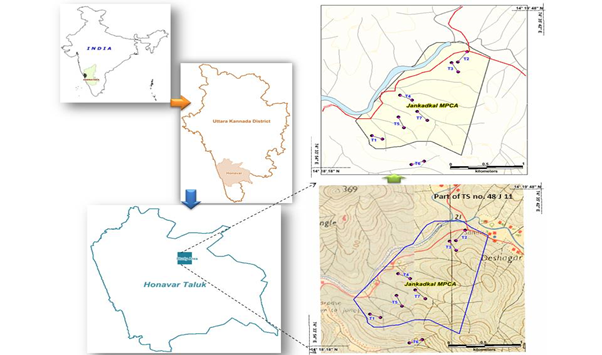

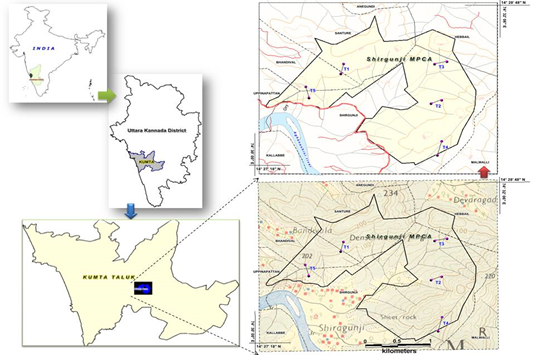

1.1 Study area and Methods: The study was carried out in two MPCA’s of Jankadkal village of Honnavar taluk (Figure 1.1) and Shirgunji village of Kumta taluk (Figure 1.2), in Uttara Kannada district, Karnataka. Both the MPCAs are in central Western Ghats, at altitudes ranging from 50 to almost 500 m above msl. The vegetation in the study area mainly comprises of tropical wet evergreen to semi-evergreen forest as the rainfall exceeds 3500 mm. Moist deciduous forests mixed with savannas are found in areas disturbed by fire and deforestation. These landscape elements form a mosaic with Acacia and teak plantations, rice fields and arecanut gardens characteristic of the entire western slopes of the Western Ghats.

Studies on forest vegetation were carried out using transect cum quadrat method. Each transect with a length of 180m had alternating 5 tree quadrats at 20 m inter-distance between any two (Figure 1.3). Each tree quadrat was 20 x 20 m, in which all trees (> 30 cm GBH) were studied. Members of the shrub layer, including shrubs, and tree saplings (GBH <30 cm and height more than 1 m) were enumerated in two sub-quadrats (5 x 5m) placed diagonally inside the tree quadrat. Inside each shrub quadrat two herb layer (all plants including tree saplings of height < 1 m) quadrats were laid diagonally (1 x 1m). Total of 7 transects were laid in the Jankadkal MPCA. Each transect was linked to 5 tree quadrats, 10 shrub layer quadrats and 20 herb layer quadrats. Altogether with 35 tree quadrats, each of 400 sq.m, 70 shrub layer quadrats, each of 25 sq.m and 140 herb layer quadrats, each of 1 sq.m were laid to get a comprehensive picture of the flora, including of the medicinal plants. Such a picture would give the current status of vegetation, the status of medicinal plants and also the future trends in the population tendencies of various medicinal species. In the Shirgunji area 5 transects were laid with 25 tree quadrats, 50 shrub layer quadrats and 100 herb layer quadrats. Associated features such as presence of epiphytes, climbers, parasites, human disturbances etc. were noted.

Opportunistic survey was also carried out to list other species not encountered in the transect areas. The data from the transects were pooled into three classes, locality wise, with herb layer (<1m height), shrub layer (≥ 1m and < 30 cm GBH) and tree layer (≥ 30cm GBH) and analysed accordingly layer wise (mainly confined to tree and shrub layer as year-round survey could not be carried out especially for seasonal herbs due to short term nature of the forest, although tree seedlings were estimated and seasonal herbs recorded opportunistically). The different size classes gave the current status of vegetation and trends in regeneration of forests. From the overall plant diversity data collected medicinal plants were identified using standard literatures and local consultations and data analysed using standard vegetation analysis procedures.

1.2 Data analysis: Data analysis was carried out using various ecological parameters. To access species diversity, dominance and equitability, Shannon diversity, Simpson dominance, and Peilou’seveness index were used. To analyse the vegetation characteristics (dominant and co-dominant species), Importance Value Indices (IVI) were calculated for each species. IVI takes into consideration the number of individuals (density-rD) belonging to each species, their basal area (dominance-rB) and distribution (frequency- rF) in the plot (Table 1.1 for the formulas).

Figure 1.1. Location of Jankadkal MPCA with sampling locations (T1 toT7)

Figure 1.2. Location of Shirgunji MPCA with sampling locations (T1-T5)

Figure 1.3. Transect cum quadrat method of forest vegetation study

Table 1.1: Details of indices and formulas used

|

Index |

Equation |

Notes |

% Evergreenness (trees) |

No. of evergreen trees X 100

Total no. of trees |

To estimate how evergreen a forest is. |

% Endemism (trees) |

No. of endemic trees X 100

Total no. of trees |

Percentage endemism of a forest patch |

Basal area (m²) |

(GBH)²/4π |

|

Important Value Index |

R. density + R. frequency + R. basal area |

To know dominant and co-dominant species |

Density |

No. Species A

Total no. of trees |

Provides information on the compactness with which a species exists in an area. |

Relative Density |

Density of Species A x 100

Total density of all species |

|

Frequency |

No. points with Species A

Total No. points Sampled |

Provides information on the repeated occurrence of a species |

Relative Frequency |

Frequency of Species A x 100

Total Frequency of all Species |

|

Relative basal area |

Basal area (m²) of Species A X 100

Total basal area of all species |

|

Shannon Weiner’s diversity index |

|

The value of Shannon’s diversity index is usually found to fall between 1.5 and 3.5 and only rarely surpasses 4.5. |

Simpson’s dominance index |

|

|

Pileou’s evenness |

Shannon value/Log(Total number of species) |

|

|