Chapter 6: Beekeeping Scenario

6.1. Introduction

Honey was an item traded from the south Indian west coast from time immemorial. Most of the honey collection was from wild sources or from semi-domesticated sources wherein often earthen pots with narrow mouths (especially water pots) where fixed to large trees for attracting bee colonies. In Uttara Kannada, the number of beekeepers was stated to be about 5300 in 1900-91. In 2002, after the passage of a century, the number of bee keepers got reduced to merely 1550, according to Bhat and Kolatkar (2011). There could have been different reasons for showing such low number. Firstly, the figures could have been obtained from the bee-keeper’s co-operative societies in the district. It needs to be stated that all the bee keepers are not necessarily members of such societies. Therefore it is difficult to get a picture of the ground reality. Further, the closing years of the last millennium witnessed bee colonies perishing in large numbers all over the Western Ghats areas due to the spread of the Thai sac brood virus epidemic. Our studies at the village level, admittedly though far from complete, reveal that many bee keepers are not necessarily members of the societies, nor they sell their products like honey and beeswax to the societies. Therefore, it can be stated with certainty that, bee-keeping remains to be an unorganized sector despite its increasing attractiveness and rising demand for honey in domestic and international market. The district, with over 60% of its lands under forest cover, and about 15% under agriculture, has a huge potential to be a stronghold of honey production, at least in peninsular India. It is a field where scores more can find fruitful employment, not impacting the environment in any manner, except beneficially, through increased pollination, fruit and seed setting in both crop and wild plants. If combined with appropriate environment management the employment potential could be very high, next only to agriculture and fisheries. Through interviews of over 100 individual farmers from the coastal and interior malnadu taluks as well as using the information furnished by some of the notable bee keepers co-operative societies we have been able to provide a picture on bee keeping in Uttara Kannada.

6.2. Materials and methods

The study on bee keeping was carried out in six of the 11 taluks Uttara Kannada district namely: Ankola, Kumta, Honavar, Yellapur, Sirsi and Siddapur from November 2011 to March 2012. Details of Uttara Kannada district, geography, topography, climate etc. are given in the chapter 5. Primary data was collected from randomly selected villages and towns, through interviews with help of a questionnaire (Annexure-II). The locations of field study sites, pertaining mainly to visiting the bee-keepers, are given in figure 6.1. and 6.2. About 105 bee-keepers from 83 villages from six taluks (Annexure II) were interviewed, about the number of boxes they kept, honey production, processing, marketing, important bee-forage plants, types of honey and on problems and prospects of bee-keeping. Their bee colonies were also examined wherever possible.

Figure 6.1: Field study localities (indicated with stars) in Uttara Kannada district

6.3. Results and discussion:

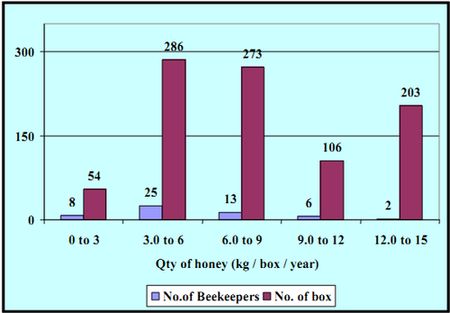

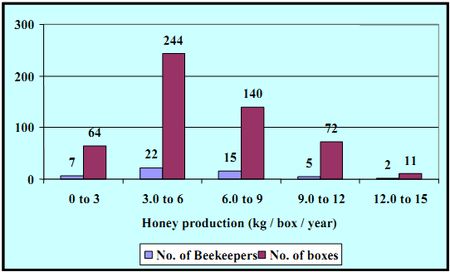

Annual honey production/box

The 105 bee-keepers whom we interviewed owned 1453 bee boxes, at an average of 14 boxes each. The total honey production amounted to 10,424 kg, during the year 2011(Table 6.1), at a district average of 6.68 kg/per bee box. Taluk-wise per box honey production ranged from 5.73 kg in coastal Honavar taluk to 9.45 kg in Sirsi taluk of malnadu region. Of the other coastal taluks the average of Kumta was 5.94 kg and Ankola had 6.72 kg. Siddapur in the malnadu region had 5.96 kg/box and Yellapur had 6.29 kg/box. These details show that apart from Sirsi taluk the other taluks, whether interior or coastal, did not show any notable variation in annual honey production per box. The actual honey production ranged from 0.8 kg to 14.7 kg in a box / year. Exceptionally high production /box at 12-15 kg/yr for the coast was reported by a couple of bee-keepers, who together had 11 boxes. Such high production was noticed in Hodike-Shirur and Kadle-Koppa villages of Honavar. The lowest production for the coast was noticed in Belekeri village of Ankola and Mirjan of Kumta. Belekeri village has very poor vegetation for the coast as it being the seat of a minor port was ravished by iron ore transport beyond its carrying capacity. Mirjan, situated towards the bank of Aghanashini estuary, although is hilly for most of its terrain, the major vegetation is monoculture of the exotic Acacia auriculiformis, which is not a nectar producer. Krishana B. Gunaga of Alageri village in Ankola, close to Belekeri port village, has the practice of keeping his bee colonies in his native village until the close of flowering of the soapnut trees in December. Soapnut honey fetches a very high market price of about Rs.1000/kg. Thereafter, in mid February or so he transports his bee colonies to the rather densely forested Hillur and Yana villages towards the interior of the coastal region and installs them there until the end of April. This is a period of widespread flowering of forest plants which benefits him considerably to increase the honey output. Some other coastal bee-keepers also follow such good practice. Inner coastal villages have greater scope for bee-keeping because of better vegetation than along the coast and the nearness of the better forests in the interior to which they can shift their bee colonies when gregarious flowering begins. Details of the number of beekeepers surveyed and honey production/box/year in the coastal taluks and malnadu taluks are given in Figure 6.3 and 6.4 respectively

Situation in the malnadu villages is not much different from the coast, barring a couple of farmers, one from Kodkani village of Siddapur and the other from Kallalli village of Sirsi. Together these two farmers own 203 bee boxes and get high yields ranging from 12-15 kg/box/yr. Their villages have good vegetation and both of them have also good management practices. Wherever bee forage plants, especially nectar plants are less, scope for good honey production is bleak. The major problem of the bee-keepers in the interior hilly terrain is the scanty availability of bee forage materials during November to January. There is more need to enrich such areas with various early flowering herbs and other species until the forest trees come into bloom. These bee keepers require alternative locations, apart from their own private lands, during the lean season, to keep their bee boxes. Some of the malnadu farmers also get the benefit from the early flowering of the soapnut trees of the coast, by shifting their colonies and thereafter they return to their interior villages to get the benefit of summer blooms of forest plants.

Difficulties in evaluating the actual bee-keeping scenario

Most of the beekeepers interviewed were not in the habit of selling their products to the society, because of the lower prices such products fetch. It is difficult to estimate how many bee-keepers are there in Uttara Kannada through short term studies. Even in the 83 villages covered by us we could not meet all the bee keepers. Most of the terrain covered is hilly with often isolated houses or dispersed in small hamlets. Considering the fact that there are about 1200 revenue villages, in addition to over a dozen towns, the bee keeping, despite its waned state, is still an enterprise large enough to merit more detailed studies and assessment of potential for the future. The fact that nearly 7 kg of honey production per box, fetching an annual income of anything between Rs.2000-Rs.3000 per box maintained, reveals the enormous hidden potential of this enterprise to boost rural incomes through this eco-friendly activity which incidentally will also enhance agricultural income through pollination services from the bees. Further, our study does not cover honey collected from the wild by an uncounted number of persons from the villages close to the forests. Most of these activities are being carried out without any kind of special assistance to the farmers from the state. The study underscores the fact that if beekeeping is promoted and supported in all potential areas, Uttara Kannada can produce enough honey not only for domestic consumption but also for export.

A male-dominated enterprise

The family sizes of bee-keepers in the study area ranged from 2 to 16 persons at an average of 5.25. Wherever we surveyed it was found that bee-keeping was mostly a male dominated field. Greater female participation is necessary so as to increase the economic and nutritional security of especially the rural households. Motivation and training for women are necessary in this regard. Domestic use of honey in the households of the producers, despite its high nutritional quality, was poor. It varied from a minimum of 0.5 kg/yr to about 400 kg/yr in an exceptional case of a bulk producer from Sirsi, who has almost entirely replaced the household use of sugar and jaggery with honey and claims that to be the major reason for the good health of his family.

Bee-keeping for the landless

Although landed bee-keepers constitute a more privileged class, in Uttara Kannada there is good scope for the landless, especially in the villages, to adopt bee-keeping. Ganapati T. Naik of Bisgod village in Yellapur taluk, a landless person, owns about 60 boxes which he keeps in and around the village and earns a good income. He also sells bee colonies to others. The forest department should patronage the bee-keepers to use appropriate areas in the forests for keeping the bee-boxes, and as well as enrich the forests closer to villages with especially bee forage wild plants.

Table 6.1: Details of honey production during 2011 gathered from bee keepers in six taluks

| Taluk |

Persons interviewed |

No. of Boxes |

Qty (Kg) |

Average (Kg) |

| Ankola |

14 |

152 |

1021 |

6.72 |

| Kumta |

20 |

270 |

1604 |

5.94 |

| Honavar |

17 |

109 |

625 |

5.73 |

| Yellapur |

11 |

309 |

1945 |

6.29 |

| Sirsi |

14 |

451 |

4264 |

9.45 |

| Siddapur |

29 |

162 |

965 |

5.96 |

| Total |

105 |

1453 |

10424 |

6.68 |

Figure 6.2: Beekeepers surveyed, number of bee boxes and average honey production/ box/year in the coastal taluks (Ankola, Kumta and Honavar) of Uttara Kannada

Figure 6.3: Beekeepers surveyed, number of bee boxes and average honey production/ box/year in the malnadu taluks (Yellapur, Sirsi and Siddapur) of Uttara Kannada

Plate 6.1: Kinds of honey produced by a bee-keeper in Sirsi taluk; 1. Terminalia paniculata; 2. Carallia brachiata; 3. Syzygium cumini; 4. Strobilanthus spp./Carvia callosa; 5. Sapindus laurifolius; 6. Gliricidia sepium

Types of honey

The district produces a variety of honey types, mostly of organic origin. The honey type depends on the dominant kind of nectar sources of the season, which determines the colour, aroma, composition and taste. The composition of honey varies, depending mainly on the source of the nectar(s) from which it is originated and to a lesser extent on certain external factors, for eg. climatic conditions and bee keeping practices (White 1975). We could document seven types of honey from Sirsi taluk. Of these six types are unifloral honey mainly from the flowers of Terminalia paniculata (Honagalu honey), Syzygium cumini (Neerilu honey), Carallia brachiata (Andamurugilu honey), Strobilanthus spp. & Carvia callosa (Gurige honey), Sapindus laurifolius (soapnut or Atalakai honey) and Gliricidia sepium (Goppara) Plate: 6.1). Most commonly two kinds are recognized locally viz. mixed and soapnut honey. The demand for unifloral honey such as from soapnut is very high compared to mixed honey. It would be, therefore, beneficial to plant large number of soapnut trees in the district, especially in the coastal taluks. Even though the quality of honey was identified in three ways like physical, chemical and biological methods, most local people grade the honey by its taste, viscosity, smell and colour.

6.4. Recommendations

1. Trainingprogrammes

- Honey production: theory and awareness: There is large number of aspirants for apiculture in Uttara Kannada. If proper awareness and training programmes are conducted bee keeping can be a major income-generating activity especially in rural areas. Many people have interest; yet they are scary of bee stings or about gaining profits due to lack of encouragement and proper knowledge. By appointing adequate number of trainers, directly by the Government, or commissioning experienced bee keepers from the district itself as trainers, on honorary basis, the bee keepers’ societies can still play key role in promoting this enterprise and bring it at par with China, the world’s highest producer of honey. The trainers need to conduct the programmes at two levels. Using power point presentation, especially at panchayat level they can impress upon the village community on the importance of bee keeping. A selection can be made of prospective persons who can be given the second level of training with more practical components, including a series of visits to successful apicultural farms in the district and outside. Relevant literature on bee keeping theory and techniques should be provided to the trainees free of cost.

- Using wild colonies from the jungles for domestication through traditional expertise: Many local villagers, especially belonging to the communities such as Halakkivokkals, Siddis, Kumri Marattis, Kunbis etc. have the knowledge of collecting wild bee colonies and transferring them to the bee-keeper’s boxes. This is a much cheaper method, costing about Rs.300- Rs.500, per colony transfer. At the same time purchasing such a colony at market prices will cost anything between Rs.1200-Rs.1700, which many cannot afford. Caution is necessary regarding the timing of bee colony collection from the wild as the period from late March to early June is honey collection period from the forests. It is recommended strongly that for rearing purpose jungle colonies may be transferred to the brood chamber of the bee box during September and October. By February the box will be full of bees, all the seven to eight frames occupied by the bees through multiplication within the box itself. The bee box starts yielding honey from February to end of May. As this is the flowering season for most forest plants and horticultural crops, honey from the boxes can be collected at intervals of seven to 14 days.

- Populating new boxes:A well maintained bee box can accommodate seven to eight frames of bees in the brood chamber. Each brood chamber is topped with a super chamber, from which alone honey has to be extracted as the brood chamber honey has to be kept in the reserve for the sake of the growth and functioning of the colony. Once the newly trained bee-keeper, becomes successful in rearing honey bees, he needs training in developing new colonies for introducing in more boxes in his own farm. He can even trade surplus colonies to others. To develop a new colony the bee-keeper may remove four frames with honey bees to a new bee box where already four empty frames are fixed. The new bee box to be populated has to be kept as far away from the original colony so as to prevent the migration of the queen from the old box to the new.

- Regulating the number of queen bees: Normally one bee box should have only a single queen bee. If an additional queen tends to develop by chance in a larger cell the worker bees will not provide royal jelly critically necessary for maturity of the queen bee. By mistake if an additional cell with developing larva gets stored with royal jelly one more queen develops in the same box. If more than one queen develops in a bee box it is likely to fly away from the parent box to establish a new colony elsewhere. Her flight is often accompanied by a horde of thousands of worker bees, deserting the parent colony, leading to its collapse, as less number of workers is left here to gather pollen and honey. The bee-keeper should keep an eye on such disorders in the colony and remove the extra queen cell itself or destroy the larva developing in the queen cell.

- Screening for healthy queen bees: The setting up of a healthy colony depends on the quality of the queen bee. If the queen bee is undersized or unhealthy or infected with parasitic mites it will affect the egg laying capacity, or the eggs hatch into undersized bees etc. The bee keepers are to be guided to select every year a new queen for the colony as it has greater egg laying capacity leading to more number of healthy worker bees resulting in greater honey production.

- Ideal time for setting up new colonies: Separation of a queen bee for setting up a new colony has to done before September, in the conditions of Uttara Kannada. After September with the beginning of overall flowering season the bees become active collecting nectar and pollen for brood development and therefore the worker force has to be maintained in the box.

- Shifting bee boxes for greater production: An atmosphere of goodwill has to be created among the bee keepers and the general public so as to facilitate the bee keepers shifting the boxes of bee colonies to places with good amount of bee forage plants. Considering also the fact that bees are tremendous forces in pollinating horticultural crops and forest trees, various other medicinal plants etc., the farmers and foresters should welcome bee keepers to set up the bee boxes in their farms and forests respectively. In a small way however, ‘nomadic’ bee-keeping is happening in the district. For instance most of the soapnut trees (Sapindus laurifolius), the sources of the highly priced soapnut honey, are concentrated in the coastal taluks. Soapnut trees are the earliest to flower, November-December being their blooming period. Some of the bee keepers from the interior villages set up bee boxes in the coastal taluks on mutual understanding with the locals, so as to harvest soapnut honey, the first honey of the season. Likewise some of the coastal bee keepers also shift their bee boxes into interior hill ranges to derive benefit of the peak flowering season of a variety of wild plants.

Shifting colonies in search of flowers

K.B. Gunaga of Alageri, a sea coast village of Ankola taluk, and one of the best producers of honey from the taluk, as well as a member of the local society, finds it hard to get any honey, except from soapnut trees of the coast. The large-scale raising of Acacia auriculiformis plantations along the coast has adversely affected wild plant growth necessary for bees. Therefore the farmer shifts his almost 40 boxes into Hillur and Yana, well-forested villages, in the interior, from mid-February onwards to reap maximum benefit from mass flowering of a great diversity of plants. The shifting of the bee boxes has to be done only after sunset, when the bees have returned to their colonies. The entrance to the box has to be sealed with bee wax itself so as to prevent bees from flying away during transport. |

Plate 6.2: K.B. Gunaga, beekeeper of Alageri, Ankola taluk, explaining foraging bees in beehive

|

- Training in dis-infestation and disease control: Attack by mites, wax moth etc. and viral, bacterial and fungal diseases can have devastating effect on bee keeping (Chapter 4 for more details). The bee keepers are scared of such outbreaks of pests and diseases and are often in the dark about how to deal with them. The bee keepers needs training in diagnosing the ailments of the bees and in adopting preventive and quarantine measures before greater expertise to deal with the problem is made available by the Government.

- Protection from predators: Ants can be a menace on the bee colonies as honey in the hive is a great attraction for them. The use of water stored in containers around the legs of the box is the safest and most eco-friendly measure for keeping away the ants from access to bee colony. Awareness should be spread against the ill effects of chemical pesticides for that purpose. The attack by carpenter bees which capture and carry away honey bees to feed their young ones is almost an unsolvable problem that needs experts’ attention.

- Optional feeding during lean periods: The farmers need to be instructed about the importance of conservation of honey in the super chamber of the colony during the lean periods, especially the rainy season, when practically the bees do not get any food. There is the general practice among the bee keepers of providing sugar or jaggery solution as feed for the bees. Although the bees live feeding on such substances, these being mainly of sucrose, provide only calories and not the proteins vital for development of the larvae. Protein rich gram flour (from black gram, soybean, Bengal gram etc.) made into a paste with sugar and honey may be better option to provide vital nutrients to the adults and developing bees.

- Awareness on pollination benefits: The great role of bees in pollination of especially horticultural crops need to be highlighted in the training programmes, through excursions to such farms with pronounced yield increase because of bees and through invited talks from such bee-keeper farmers. It is not merely extraction of honey for trade purpose that should motivate the farmers; the role of bees as pollinators to achieve higher yields and quality fruits and seeds is also very important. The bee keeping has to be ingrained as a culture among the farming community and even among the rural landless for the multiplicity of benefits that include income from honey, nutritional security and pollination of both cultivated and wild plants.

- Awareness on organic farming: The widespread and indiscriminate use of pesticides in the agricultural sector can be detrimental to bee keeping. The evils of pesticide application can be far reaching on human health as well as of the various beings in the ecosystem. The honey bees are very susceptible to the toxic effects of pesticide use as organophosphates can be deadly neurotoxins on them. The pesticide use is becoming a widespread practice in the coastal areas than in the interior of the district where organic farming is more popular. During our survey, we came across a case of organophosphate application on sweet potato crop in Bijjur village of Gokarna panchayat that caused death of honey bees in five boxes in the vicinity.

2. Forests in support of beekeeping

In Uttara Kannada district most human settlements, barring some major towns, are dispersed among forest lands. These forest lands might be having already good vegetation, or may be poorly vegetated; for instance, the coastal minor forest belt is substantially barren or supports only scrub and Acacia plantations. These are not good places for healthy bee colonies, and naturally, there are less people on the coast having interest in apiculture. In the interior villages the forests may be rich or may be a combination of diverse landscape elements which include monoculture plantations (teak, Acacia etc.), scrub jungle, savanna, betta (leaf manure forests which are often heavily lopped). Our surveys and interviews with the bee keepers reveal that good vegetation with several species of nectar plants are very essential for enhancing honey production. Therefore we recommend the following:

- Enrichment of coastal minor forests with bee forage plants: The ground in the coastal minor forests is very eroded, rocky and compact, often lateritic, or strewn with granitic boulders and fragments. The laterite formations of Kumta to Bhatkal have been destitute of good vegetation even before the British arrival in Uttara Kannada. Human impact seems to be the major reason for the general state of vegetational devastation of the coast. Once the original vegetation is destabilized through cutting and burning, for repeated cultivation or cattle grazing, the torrential monsoon rains erode the exposed soils and thereafter the hot sun bake the surface creating hard lateritic surfaces. These coastal hills and plateaus at the most could support scrub or savanna and some kind of stunted semi-evergreen forests where the soil conditions are better. During the last two to three decades a good lot of these areas have been brought under monoculture of Acacia auriculiformis. Apiculture in the coastal villages is not all that attractive proposition in the given situation, and the bee keepers are hard to find. Some of them carry their bee boxes into the interior forested villages once the early honey, mainly of soapnut plant origin is harvested. For instance K.B Gunaga from the coastal village of Alageri in Ankola moves into the interior villages of Hillur and Yana to fix his bee boxes, from mid-February of every year, after the soapnut honey season comes to an end as the coast does not have much to offer thereafter. Likewise some of the interior taluk bee-keepers take their bee boxes to the coastal areas to take benefit of the soapnut flowering.

- The importance and profitability of soapnut tree: The soapnut tree (Sapindus laurifolius) is an excellent producer of high quality honey. It is one of the earliest to flower among the notable nectar plants, coming into bloom during November-December, soon after the rainy season. The honey, esteemed medicinally due to its slightly bitter taste and less sugar and other properties, was sold for about Rs.700/kg till a year ago and fetches these days a price exceeding Rs.1000/kg. Soapnut tree grows commonly along the coastal villages. It can be grown in a variety of soils including in lateritic areas and roadsides. Many bee-keepers demanded that soapnut tree be liberally planted by the forest department in all blank areas. On a modest estimate, if we succeed in raising 100,000 trees, at the average rate of three kg of honey per tree, each kg fetching Rs.1000/- at current market prices the potential income from one lakh soapnut trees could be Rs.30 crores. Apart from income from honey, the soapnut fruit is a non-timber forest produce used in production of soap and cosmetics. The tree will provide also a good cover for the open lands subjected to high degree of soil erosion.

- Need for improving the betta forests: The bettas are forests allotted to arecanut gardeners for collection of dry leaves and lopped green leaves from trees as manure for their gardens. Betta allotment is highest in Sirsi, Siddapur and Yellapur taluks where horticulture is most important. Most of the bettas have today heavily lopped trees; they have open canopy and poor vegetation on the ground. Good bee-keepers shy away from keeping their bee boxes inside or closer to these bettas. Therefore, we suggest here that at least one third of the betta lands be enriched with bee forage plants, and the forest and horticulture departments should provide necessary guidance to the farmers and supply saplings of these bee forage plants.

3. Government assistance for bee-keepers

The Government may help bee-keepers with necessary equipments than with cash subsidies. The Government assistance may also include enrichment of bee flora in the village areas and the forests around, by planting such species along roadsides, public premises etc. Free guidance programmes should be taken up to help rural entrepreneurs to take up bee keeping, for purification and packaging honey and in disease prevention and control. Subsidies and loans are to be restricted to the functional boxes only so that Government aid is not misused.

4. Guidance for honey hunters

Honey hunting in the wild often happens to be destructive exercises. The bees are driven away with fire and smoke and the entire hive pulled down and squeezed to extract honey causing destruction of thousands of eggs, larvae and pupae. The honey hunting in the wild should be using sustainable methods. The Village Forest Committees and bonafide forest dwellers like Kunbis, Kumri Marattis, Karivokkaligas, Siddis etc. alone should extract honey on sustainable basis from only areas designated for the purpose by the Forest Department, leaving behind sufficient stock of untapped beehives so as not to decimate the genetic stock of wild bees very necessary for infusing resistance into the domestic bees, as the bee boxes are often colonized by capturing wild bees of the species Apis cerana. The Forest Department may periodically take stock of the situationand decide to close certain area of forests to honey collections, which are under threat from overharvests, until such areas recuperate well. The bonafide honey collectors may be provided with protective uniforms and awareness on scientific collection and processing techniques.

5. Bee colony heritage trees

The bees, especially Apis dorsata, prefer certain large trees such as Tetrameles nudiflora for establishing their colonies. Any such tree with more than ten colonies may be considered for declaration as a ‘heritage tree’ under the provisions of the Biodiversity Act-2002 of Government of India.

6. Prospects of beekeeping in mangroves

Mangroves play an essential role in maintaining a healthy coastal environment by providing protection for aquatic species, functioning as a habitat for a variety of terrestrial fauna, in improving coastal protection and acting as a source of nutrients that sustains many complex food chains. These swamp forest communities are often employed in promoting shrimp cultures (Olsen and Maugle, 1988; Stonich, 1992). A variety of renewable products including timber, food, charcoal, firewood, honey and medicine are traditionally obtained from mangroves by many local communities world-wide (Kovacs, 1999).

The mangroves are good producers of honey. Forest Survey of India (1999) estimated about 487,100 ha area under mangroves in the country. The Sundarbans, which has largest area under mangroves, has been a major production centre for honey. It accounted for 111 tons of honey production, which was 90% of the total honey from mangrove areas of India (Krishnamurthy, l990). Phoenix– Excoecaria combination of trees associated with mangrove swamps offer ideal habitats for honey comb formation in the wild in the Sundarbans, accounting for maximum number of combs per unit area. Rhizophora and Avicennia (A. alba and A.officinalis ) also accounted for good number of combs. Aegiceras corniculatum and several mangrove associates are useful for honey production. Area under mangroves is steadily under rise in Uttara Kannada during the recent years due to consistent efforts made by the forest department. If more attention is paid to the planting of nectar producing species more people from the coast will be benefited by bee keeping.

7. Importance of organic honey production

The demand for organic honey is on the rise in developed countries. Honey production from intensive agricultural landscapes, because of usage of chemical pesticides and fertilizers cannot be termed as organic. Bulk of Uttara Kannada’s honey production probably would fall in the organic category on account of the cattle and forest dependent farming practices. The district needs to capitalize on this and intensify production of organic honey for export, supply to pharmaceutical companies and for domestic consumption.