Results

Unique Spatial Patterns

A concentric ring pattern of CO2 emissions is discernible among

household samples in Xi’an, waving downward from the inner city

then upward towards the outer ring. In Bangalore, the high level

emission households are distributed sporadically, interspersed with

low emission households in multiple clusters all over the space.

Distinctive Family Characteristics

Families in Xi’an are smaller than their counterparts in Bangalore.

About 60% of the households in Xi’an are three-member

families. In Bangalore three member families only account for 15%

of the samples. Instead, almost half of the samples in Bangalore are

four-person families. In Xi’an four-person families only account for

10% of the samples. The largest family reported in the Xi’an sample

has 8 persons, while the largest in Bangalore has 33 persons. About

2% of the household samples in Xi’an have 6 persons or more, but in

Bangalore about 13% of the samples have 6 members or more.

Distinctive Housing

The majority of the households in Xi’an live in walk-up apartments

(64%) or high-rise apartments (32.5%), while in Bangalore a

large proportion of the households live in single storey houses (41%)

and walk-up apartments (42%). A larger proportion of households

live in newer apartments in Xi’an than in Bangalore, and the unit

size of housing is smaller but less varied in Xi’an as compared with

Bangalore.

Modernisation as a Key Driver Towards High CO2 Emissions

In both cities the ownership and usage of motor vehicles show

positive influence on CO2 emissions, though the ownership and

usage vary greatly. About 20% of the family heads commute by car or

motorcycles in Xi’an but in Bangalore the proportion is above 60%.

However, among the families that use motor vehicles, the average level of petrol consumption in Xi’an (149 litres per month) is higher

than that in Bangalore (45 litres per month); this is due to the popular

use of motorcycles in Bangalore. In contrast, more than half (52%) of the family heads and their spouses in Xi’an walk or cycle to work,while in Bangalore only about 11–20% of the family heads and their

spouses walk or cycle to work.

The use of electricity is measured by the number of household

appliances in Xi’an but the use of electricity for cooking in Bangalore.

This choice of measurement reflects the different characteristics of

on-site energy use in the two cities. About 56% of the families in Xi’an

use six or more electric appliances such as refrigerator, microwave,

TV, etc. In Bangalore, about 54% of the families use electricity for

cooking.

In terms of income, the proportion of samples in each of the

highest three bands (US$ 1668 and more) are quite similar between

Xi’an and Bangalore. But the poorer households form a larger

proportion in Bangalore (25%) than that in Xi’an (7%). According to

the accumulative percentage values, there are 5% more samples that

earned a monthly income of US$ 833 and less in Bangalore than that

in Xi’an.

The 1 km zone as a Planning Unit to Reduce CO2 Emissions

A rich mix of economic activities within a neighbourhood space

(about 1 km radius from home) is associated with low household CO2

emissions. This is confirmed by both the aggregate household emissions

model and the commuting-related emissions model in Xi’an.

A related finding is that a rich mix of services and facilities, such as

kindergartens, primary and secondary schools, supermarkets, banks

and hospitals, in the immediate vicinity (within 500 m radius) of a

household is associated with higher emissions from the household.

These results are not contradictory as they represent different

aspects of the built environment. The provision of more services and

facilities within the immediate zone contributes to the formation of

a prestigious residential environment, thus higher house values and

wealthier families are more likely to be found in the area – apparently,

wealthier families are associated with higher CO2 emissions.

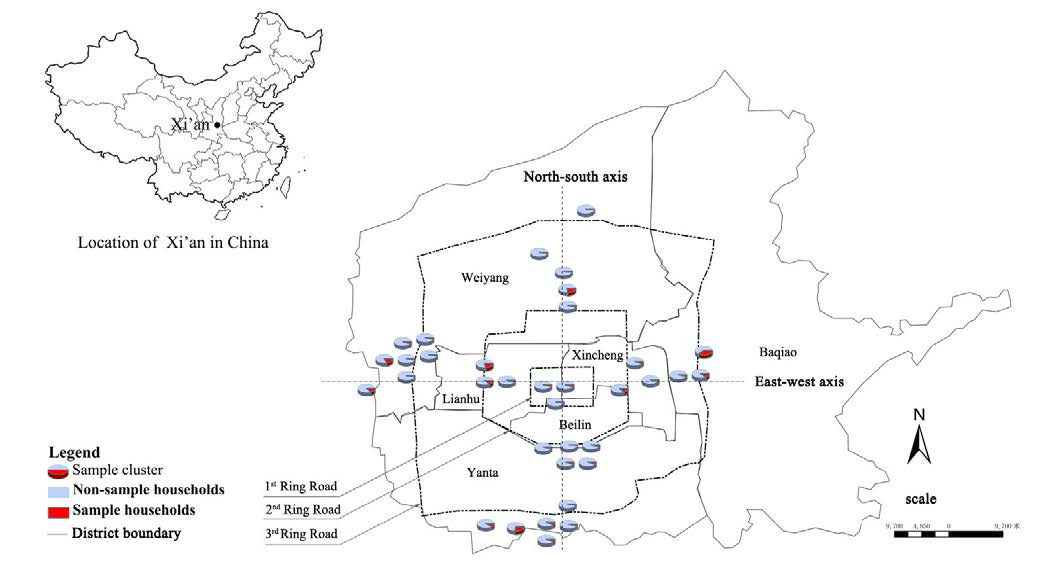

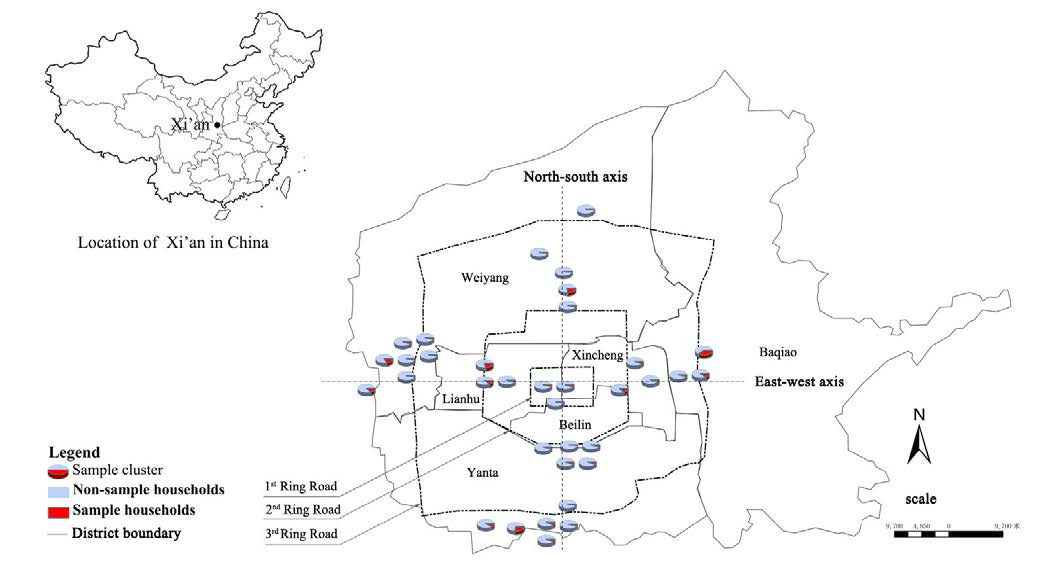

Figure 1. Sample households selected from housing blocks/groups including market housing, municipal housing and work-unit housing

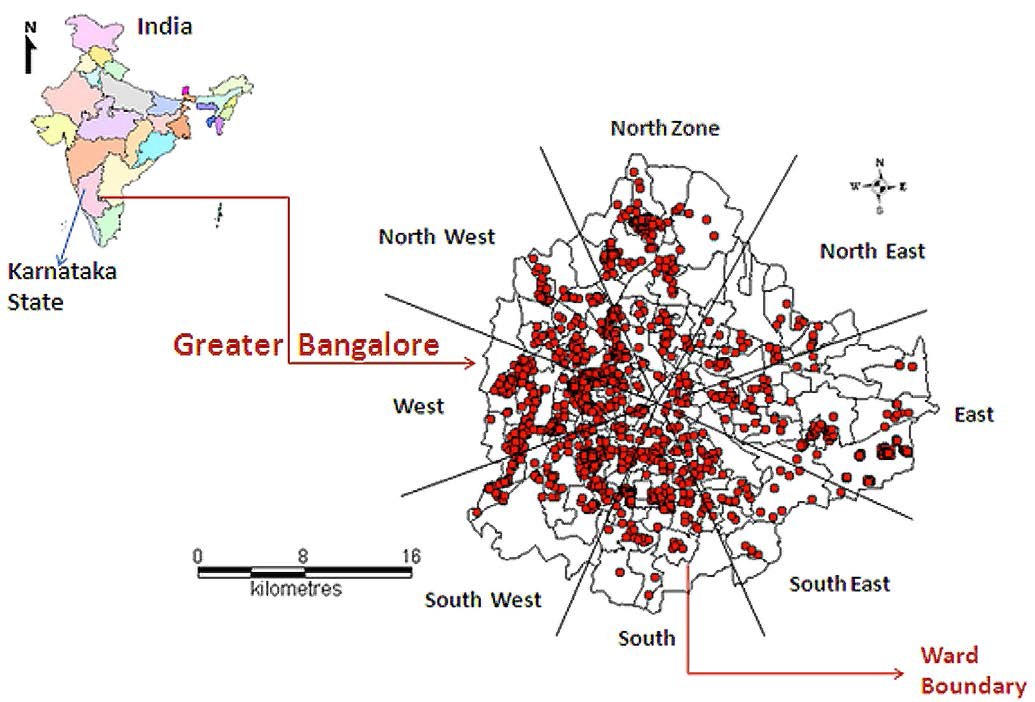

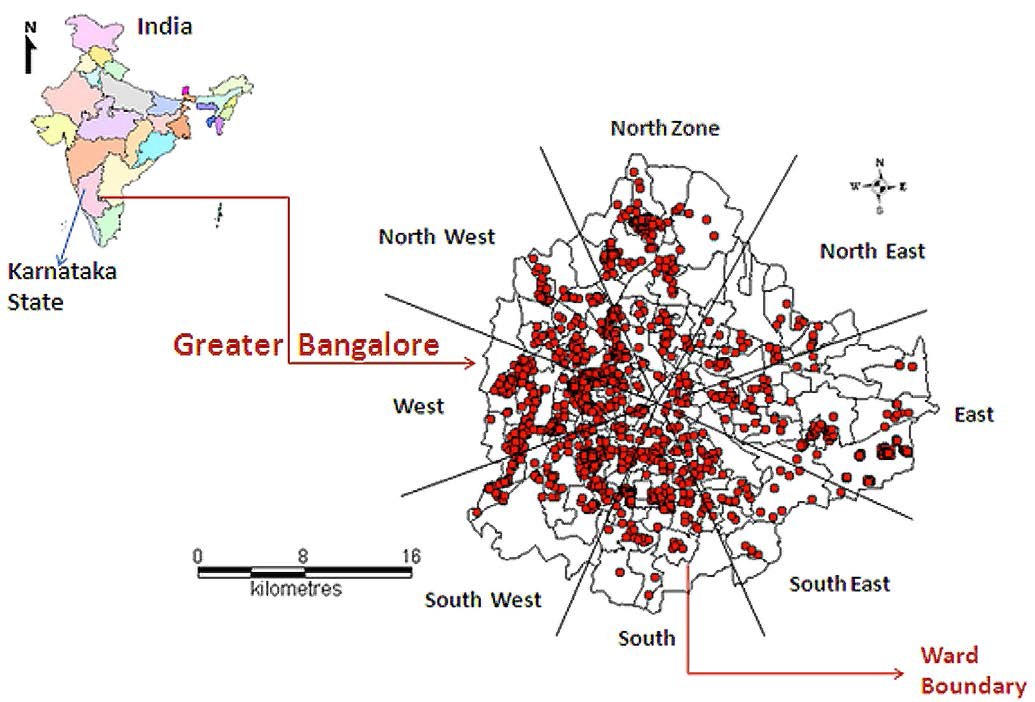

Figure 2. The spatial distribution of sample households in Bangalore.

Households in Xi’an are more likely to be surrounded by a

richer mix of services, facilities and jobs than their counterparts in

Bangalore. In the immediate vicinities of households in Xi’an, more

than 60% of the samples are surrounded by eight or more service

and/or facility types. This same measurement is much smaller in

Bangalore (less than 30%). Less than 4% of the sample households in

Xi’an are surrounded by one or two service or facility types, while the

same measurement reads 20% in Bangalore. Within the neighbourhood

space, more than 50% of the sample households in Xi’an are

surrounded by four or more job types, while in Bangalore the same

measurement is about 12%. About 30% of the samples in Xi’an are

surrounded by one or two job types, while in Bangalore the percentage

is as high as 73%. This same pattern is true for the extended

neighbourhood defined by a 5 km radius from home.

Citation : Sun Sheng Han, Yuan Qing Wang, T. V. Ramachandra and Bo Qin, 2015. The Impact of Spatial Parameters on Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Emissions: A Comparative Study between Cities in China and India [ARCP2011-07CMY-HAN], APN Science Bulletin, Issue 8, March 2015, Pp 6-7.