STUDY LOCATION

WESTERN GHATS

At the great mountains on the west coast of peninsular India are one of the richest biological areas of South Asia, the Western Ghats, one of the 34-biodiversity hotspots of the world (Myers et al, 2000) covering 5% of India’s land area. The Ghats run up to 1600 metres from the southern most tip of peninsular India (8°N) all the way up till the mouth of river Tapti (21°N) between 73°E – 77°E longitude. Western Ghats cover a total area of 160,000 sq km containing eight national parks and 39 wildlife sanctuaries. With rainfall varying from 1000 mm to over 6000 mm along with mountain ranges that have an elevation over 2000 metres, landscape heterogeneity is abundant in the Ghats (Subhashchandran 1997, Ramachandra et al., 2007). These ranges cut across political boundaries of Tamilnadu, Kerala, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra and Gujarat. Except for the Palghat gap separating the Nilgiri ranges from the Anamalai hills the Ghats are more or less continuous. In the West the Ghats descend steeply to face the Arabian sea while in the East they slope down gradually merging with the Deccan Plateau. The Ghats support a variety of endemic flora and fauna because of the diverse habitats, which have got created due to the varying topography and climate (Menon and Bawa 1997). The original rich tropical evergreen, moist deciduous and dry deciduous forest of the Ghats today present themselves as a mosaic of natural forest types, plantations of rubber, eucalyptus, wattle, casuarina, beetlenut, fields of paddy and gardens due to degradation and human intervention into the biological system.

High species diversity and endemism is associated with the Western Ghats. Daniels (1997) quotes high levels of endemism in 2000 species of higher plants, 84 species of fishes, 87 species of amphibians, 89 species of reptiles, 15 species of birds and 12 species of mammals at the Western Ghats. The montane evergreen or shola forests of high altitudes of the Western Ghats are known to harbour a relatively rare assemblage of bird species (Pramod et al 1997) while monoculture and plantations harbour species that exhibit high values of hospitality (extent of cohesion) and high levels of ubiquity or rarity. Of the 480 species of reptiles recorded from India, 197 have been reported from the Western Ghats (Johnsingh, 2001). It has also been well established that the natural vegetation show relatively high diversity of birds, butterflies and vegetation compared to monocultures, scrub and grassland (Kunte et al 1999).

Despite demonstrating such high levels of diversity and endemism, Western Ghats is experiencing large scale deforestation due to lack of conservation measures. Fragmentation has resulted in either losses or conversion of 40% of primary forests within a span of 50 years between 1920-1970 (Menon and Bawa, 1997). Within the latter part of 30 years 85.6 km2 of forests have been converted to plantations, 42 km2 to encroachments and 36.4 km2 to reservoirs (Ramesh et al, 1997).

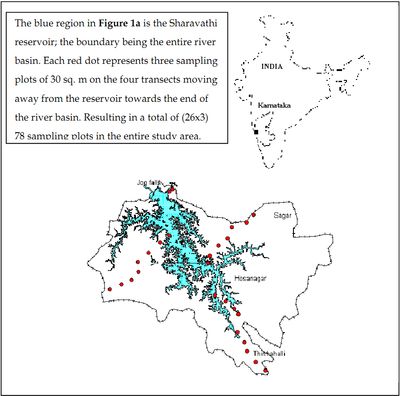

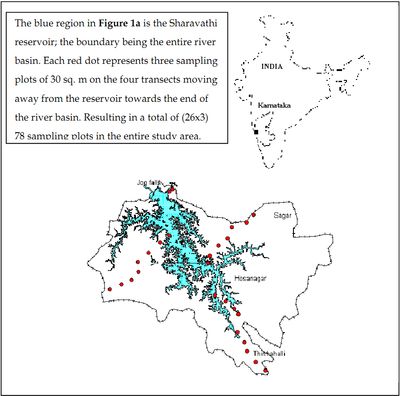

The present study was done at the Sharavathi river basin in the central Western Ghats located between 13°43'24 N and 14°11'57 N, 74°40'58 E and 75°18'34 E (Figure 1a), with elevation ranging between 80 and 1340 m. It spans Hosanagar, Sagar, and Thirthahalli taluks covering a total area of 2000 sq kms. The western part of the study area receives 2500 mm of annual rainfall while the eastern region receives 900 mm. Maximum rainfall occurs during the monsoon between June and September (data acquired from Drought Monitoring Cell, Bangalore).

Figure 1a

The western region of the study area, Nagodi, Karani and Kodachadri were rich in indicators of climax vegetation, prominent being Poeciloneuron indicum, Myristica dactyloides along with Dipterocarpus indicus, Aglaia anamallayana, Holigarna grahamii and Ficus nervosa. Certain moisture loving species as Garcinia talbotii, Mastixia arborea, Elaeocarpus tuberculatus were also present. Poor regeneration of the few present deciduous species such as Terminalia paniculata, Terminalia tomentosa, Terminalia bellarica, Lagerstroemia microcarpa, ascertained the presence of fire in the past. The shrub layer was dominated by Psychotria flavida, Pinanga dicksoni, Polyalthia fragrance, Strobilanthus species. A scrub savannah habitat with barren hilltops characterised the 25 km stretch from the reservoir on the western region to Tumri. Along the eastern region, evergreen forests were found particularly as small fragments and also only to the south. This included the Sharavathi state forest, Hilkunji, Nilvase and Kavaledurga, wherein Artocarpus hirsutus, Olea dioica, A.anamallayana, Dimocarpus longan, Vataria indica, Hopea ponga, and Knema attenuata dominated along with deciduous species as Vitex altissima and T.paniculata. The extreme level of land utilisation and encroachment seen in the planes towards the eastern region suggests the undulating topography in the southeast is responsible for remnant forests in the region. Monoculture plantations of Acacia towards the northeast were products of recent conversions of large state forests to meet the requisites of the local population and city dwellers. The eastern region had an unprecedented increase in the agricultural and wasteland area and built-up regions. With evergreen species restricted to Aporosa lindleyana, H.ponga and Polyalthia sp, the deciduous forests dominated, represented by T.bellarica, T.paniculata, Xylia xylocarpa, L.microcarpa and Buchanania lanzan. In the northeastern region, the invasive weed Euphatorium odoratum were abundant, indicating extreme degree of disturbance. Sampling plots that had 90% of evergreen trees were called evergreen forests, while less than 90% were semievergreen forests. Anthropogenic activities in recent times has resulted in large scale fragmentation, creating a mosaic of land cover patterns of agricultural fields, monocultures of acacia, eucalyptus, rubber, arecanut, pine, casuarina and cashew along with evergreen forests, moist deciduous and scrub jungles in the river basin.