RESULTS

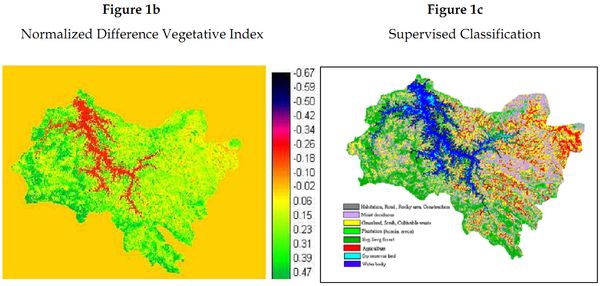

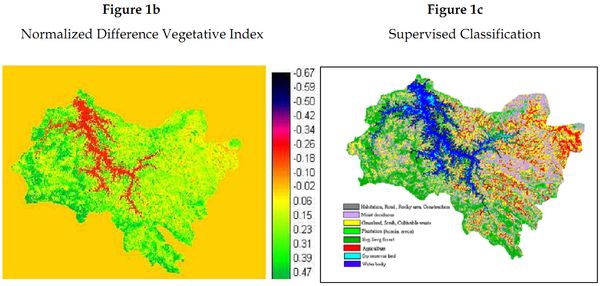

Land cover analyses: IRS-1C satellite data having a 23.5 m resolution has detected 70% vegetation cover at the Sharavathi river basin, of which 20% comprises moist deciduous and evergreen forests (Figure 1b). Field investigations coupled with satellite imagery shows large patches of undisturbed evergreen forests towards the western region of the study area (Figure 1c), while the eastern region is extensively disturbed distinct of only fragments of deciduous vegetation amidst settlements.

Ant diversity: A total of 84 species representing 31 genera and 5 subfamilies (Table 1) were collected from the study area, with an average of 9 (±3) species in 30sq.m area. Species belonging to 3 different subfamilies (Formicinae, Ponerinae, and Myrmicinae) were the most frequently occurring species for the entire study area. Ant specificity and requirement resulted in not all species being present in all the habitats. Species presence, varied from a least of 7% in pine plantations to a maximum of 76% in moist deciduous forests. Sampling revealed moist deciduous forests to harbour the most diverse ant species while evergreen forests had the highest ant species density. Scrub jungles recorded a higher species density than acacia plantations, despite having a similar species percentage (51%). Ant species were more evenly distributed in evergreen forests than the lesser but uniform evenness exhibited in the other habitats. Less than 30% of species of all subfamilies were present in evergreen forests.

Table 1: Ant composition along different habitats

| Subfamily |

Species across Forest types |

Acacia plantation |

Pine plantation |

Moist deciduous |

Dry deciduous |

Scrub jungles |

Semi evergreen forests |

Evergreen forests |

| Ponerinae |

Diacamma rugosm |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Harpegnathos saltator |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Leptogenys diminuta |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

| |

Leptogenys processionalis |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

| |

Leptogenys sp |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Platythyrea parallela |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Platythyrea sagei |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

| |

Pachycondyla henrie |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Pachycondyla luteipes |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

| |

Pachycondyla rufipes |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Pachycondyla tesserinoda |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| Dolichoderinae |

Bothriomyrmex sp |

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

Dolichoderus sp |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

Tapinoma sp |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Technomyrmex albipes |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

| Formicinae |

Acantholepis sp |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

Acantholepis opaca |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

Anoplolepis longipes |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

Camponotus angusticollis |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

Camponotus compressus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Camponotus invidus |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Camponotus irritans |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Camponotus paria |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Camponotus rufoglaucus |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Camponotus sericeus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Camponotus sp |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Camponotus (Colobopsis) sp |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Oecophylla smaragdina |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

| |

Paratrechina longicornis |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Paratrechina sp |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Prenolepis |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

| |

Polyrhachis mayri |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

| |

Polyrhachis rastellata |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Polyrhachis simplex |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Polyrhachis tibialis |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

| Myrmicinae |

Aphaenogaster beccari |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

Cardiocondyla sp |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

Cardiocondyla wroughtonii |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Cataulacus taprobanae |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

| |

Crematogaster nr dohrni |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Crematogaster rothneyi |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

| |

Crematogaster sp 1 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Crematogaster sp 2 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Crematogaster sp 3 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Crematogaster sp 4 |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Crematogaster sp 5 |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Crematogaster sp 6 |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

| |

Crematogaster wroughtoni |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Holcomyrmex sp |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| |

Lophomyrmex quadrispinosa |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Meranoplus bicolor |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Monomorium dichroum |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

| |

Monomorium floricola |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Monomorium gracillimum |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Monomorium indicum |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Monomorium latinode |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

| |

Monomorium pharaonis |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Monomorium scabriceps |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Monomorium sp 1 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Monomorium sp 2 |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Monomorium sp 3 |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Monomorium sp 4 |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Myrmicaria brunnea |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Pheidole nr sharpi |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

Pheidole parva |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

Pheidole sp 1 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Pheidole sp 2 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Pheidole sp 3 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| |

Pheidole spathifera |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Pheidole watsoni |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Pheidole wood-masoni |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Pheidologeton affinis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Pheidologeton diversus |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| |

Recurvidris recurvispinosa |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| |

Solenopsis geminata |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| |

Tetramorium sp 1 |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Tetramorium sp 2 |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| |

Tetramorium sp 3 |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| |

Tetramorium sp 4 |

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

| |

Tetramorium sp 5 |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

| |

Tetramorium walshi |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| Pseudomyrmicinae |

Tetraponera aitkeni |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Tetraponera nigra |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

Tetraponera rufonigra |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total species |

43 |

6 |

64 |

53 |

43 |

39 |

15 |

|

Percentage of species in each habitat to the total acquired |

51.19 |

7.14 |

76.19 |

63.09 |

51.19 |

46.24 |

17.85 |

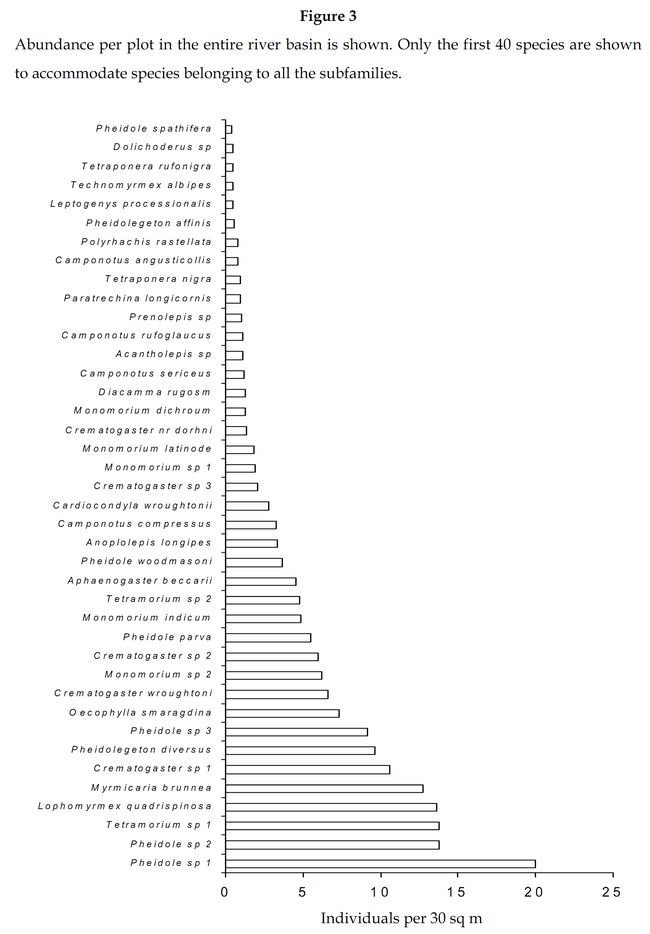

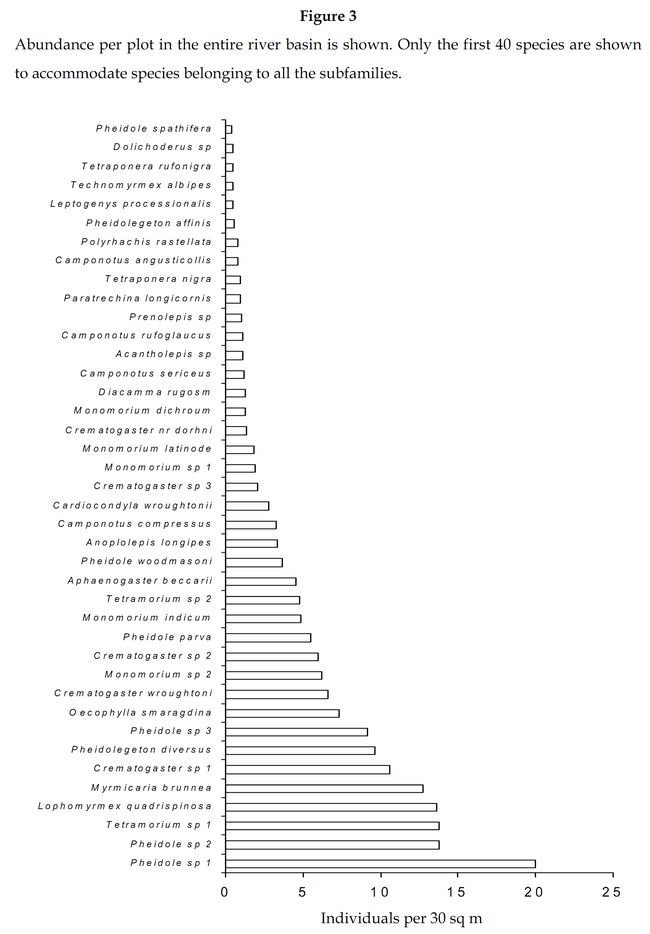

Abundance and species richness: Of the 84 species of ants collected (Table 1), Pheidole sp 1 was the most dominant (10.63%), followed by Pheidole sp 2 (7.34%) and Myrmicaria brunnea (6.77%). Solenopsis geminata, Bothriomyrmex sp, Pachycondyla tesserinoda, Monomorium floricola, Camponotus (Colobopsis) sp and Recurvidris recurvispinosa were represented by a solitary individual. Monomorium sp 2 and Monomorium indicum dominated the genus Monomorium, which was represented by 11 species. Crematogaster was represented by 9 species, wherein Crematogaster sp 1 and C.wroughtoni were highly dominant. C.sericues, C.compressus and C.rufoglaucus dominated the genus Camponotus, which was represented by 9 species. Pheidole sp 1, Pheidole sp 2 and Pheidole parva dominated the genus Pheidole, which was represented by 8 species.

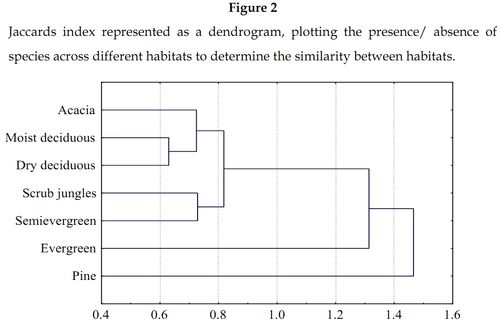

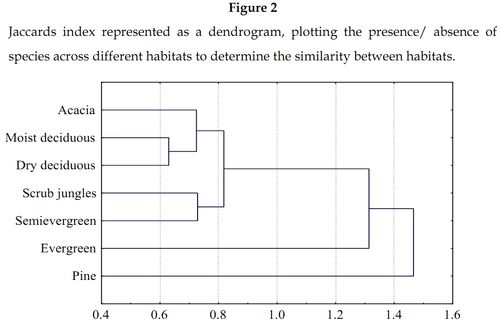

A maximum of 7.5 species per plot (30 x 30 m) was acquired from evergreen forests followed by 5.57 species in semi evergreen forests (Table 1). Moist deciduous forests were the most species rich forests with 76.19% of the recorded ant fauna (Table 1). This was followed by dry deciduous and semi evergreen forests, which had 63.09% and 46.24% of the recorded ant species respectively. Acacia and scrub jungles both had the same number of species (not the same species) with scrub jungles having a higher species per plot richness. Pine plantations recorded a lowest of six species with only one plot being sampled. A lowest of 2.06 species per plot in moist deciduous forest was attributed to a relatively large number of replicates of this forest type. Similarity tests reveal that pine plantations have extremely low levels of similarity with all the other habitats (Figure 2) except for evergreen forests wherein no species overlapping was present. They do express maximum similarity of 10.9% with dry deciduous forests. Moist deciduous and dry deciduous forests shared a maximum of 55.8% of their species.

The first, eight abundant species belonged to the subfamily Myrmicinae (Figure 3). The ninth abundant species was a Formicinae, Oecophylla smaragdina (3.92%). Further members belonging to Formicinae were ranked eighteenth and nineteenth in abundance and were represented by Anoplolepis longipes and C.compressus respectively. Diacamma rugosm was the most abundant Ponerinae (0.66%) ranked twenty sixth, followed by Leptogenys processionalis (0.26%) ranked thirty sixth. Tetraponera nigra was the most abundant Pseudomyrmicinae (0.49%)ranked thirty third followed by T.rufonigra (0.25%) ranked thirty eighth. Technomyrmex albipes was the most dominant Dolichoderinae (0.25%) ranked thirty seventh, followed by Dolichoderus sp (0.24%) ranked thirty ninth.

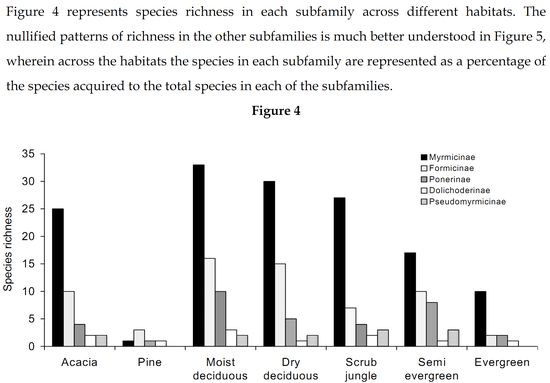

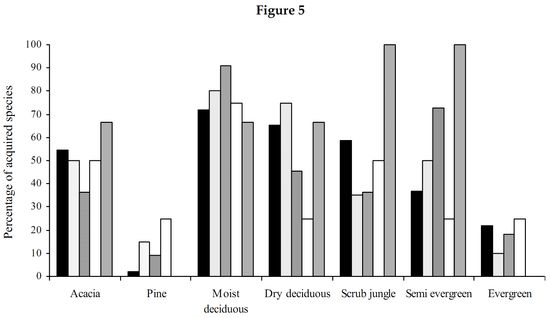

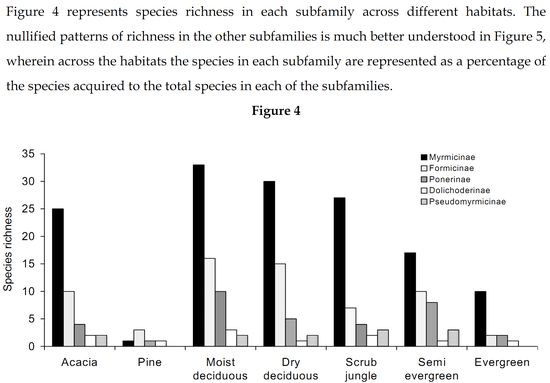

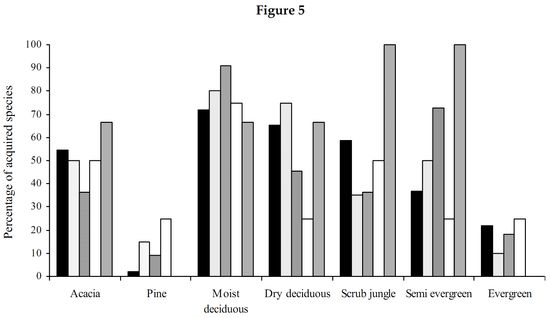

Myrmicinae: The abundance values did suggest a great dominance exhibited by the subfamily Myrmicinae. Sampling done in the seven forest types substantiates that the subfamily Myrmicinae is extremely dominant. Figure 5 depicts that more than 50% of the inhabiting species in dry deciduous, scrub jungles and evergreen forests were Myrmicines and also more than 40% of the species present in acacia, moist deciduous and semi evergreen forests were Myrmicines. This extreme dominance exhibited by Myrmicinae subfamily suggested the presence or easy availability of their food and their nesting sites. Niche and food requirements are one of the primary limiting factors of an ant population (Kaspari 2000). The highly abundant genus Pheidole had been recorded to feed on grass seeds, along with all the baits offered (species varied). Their habit of feeding on grass seeds has also been recorded by Ali (1992). Tetramorium and Monomorium also exhibited the same traits. M.indicum had been recorded to feed on insects also. M.scabriceps has been recorded to collect and store 150 – 600 g of seeds during October – December in India (Ali 1992). Certain species of Crematogaster fed exclusively on honey and few on tuna fish, while some feed on both. Also the subfamily had exclusively arboreal and terrestrial taxa. Meranoplus and Lophomyrmex had nests in open canopy areas, Myrmicaria and Apahaenogaster had terrestrial nests at tree base, Pheidole nested in soil, under leaflitter and occasionally nests had also been seen under trees. Catalaucus nested in rotten wood on trees, Crematogaster made carton nests, sometimes nesting in dead wood on trees.

High Myrmicine species percentage (Figure 5) was seen in acacia plantations (56%) and in scrublands (58%). Although many species representing Myrmicinae were present (Figure 4), the subfamily was pushed to third and fourth position in dry deciduous (65%) and moist deciduous forests (72%) respectively. They were overtaken in semi evergreen forests (36%) by species belonging to Pseudomyrmicinae, Ponerinae and Formicinae. Myrmicinae is known to have a diverse range of feeding habits with some being specialist predators, scavengers, seed harvesters and nectarivores (Majer et al. 2001). Less specificity and easy availability of the required resources coupled with varied and non-specific niche requirements and dominance in both arboreal and terrestrial zones has resulted in dominance of the subfamily Myrmicinae.

Formicinae: Subfamily Formicinae was the immediate successor to Myrmicinae subfamily. Formicines were dominant in moist and dry deciduous forests. Formicines were always second in dominance in all forest types except for pine plantation, wherein they took over from the Myrmicinae subfamily (Figure 5). The most dominant among them were O.smaragdina (Figure 3), a truly arboreal species. These ants nest in shady places and require broad leaves to stitch their nests. They were most dominant in moist deciduous, semi evergreen and evergreen forests. They were totally absent from plantations and scrub jungles (Table 1) implying on the necessity of broad leaves for their nest construction. Only a few foragers were collected from acacia plantations, only when moist deciduous forests were in the vicinity (where the nests were traced to). Dry deciduous forests did not provide shelter for these ants. The only instance wherein nest was found in dry deciduous forests was when lianas had intertwined cluster of trees and created a small narrow shaded area. A.longipes makes terrestrial nests and were dominant in moist deciduous and pine plantations. However, they were totally absent from evergreen, semi evergreen and scrub jungles (Table 1). Though dominant in moist deciduous and pine plantations they were not frequently occurring as only 22.8% of the sampled moist deciduous forests (Table 2) harbored this ant species. This species was found in areas which were disturbed and also wherein grazing, sweeping of leaf litter for manure was common. Settlements were always found close to such habitats. This species was found in acacia plantations also only when disturbance is seen and in other instances were totally absent. They did not have a liking towards close canopy and thick leaf litter niches. They preferred hard soil with canopies just touching each other. Nests were very common in walk paths in the forests used by people. They occupied all the disturbed habitats where the canopy was open for penetration of sunlight. Their absence however in the evergreen and semi evergreen forests suggests that those forests were not disturbed and close canopy areas were still persistent in these forests. With only 10% of the scrubs jungles harboring these species (Table 2), their affinity to open canopy areas was also doubtful. C.compressus was very dominant in all forest types. Absence of this species in evergreen forests was because of very few samples in evergreen forests. C.angusticollis was another dominant species present as we reached the interiors of the forest. They were absent from scrub jungles and pine forests (Table 1). Their dominancy reduced in monocultures and in dry deciduous forests. They required overlapping canopy cover for nests and areas where sunlight penetrates, for foraging. They were very specific about this requirement, which reflects in their high frequency of occurrence (Table 2) in semievergreen forests (75%). C.sericeus was one of the open canopy system specialists. They made chimney like nests in scrub jungles while they made underground nests in totally barren lands. Lands that got submerged in the monsoon season and exposed during the other parts of the year provided inhabitation only for this species. C.sericeus was a frequently occurring species in scrub jungles and dry deciduous habitats (Table 2), vouching for their preferences of open canopies and dry hard soil. P.mayri was an arboreal species present in moist deciduous and semi evergreen forests (Table 1). Plots wherein this species was found were undisturbed and were under no human influence. These plots were characteristic of thick canopy cover with no sunlight penetration and thick leaf litter. P.rastellata was extremely dominant in moist deciduous, semi evergreen and evergreen forests. They were absent from plantations. Foragers were found in scrub and dry deciduous forests only when moist deciduous or semi evergreen forests were in the vicinity. All the recorded species of Polyrhachis were arboreal and made their nests by stitching leaves.

Table 2 Species occurrence (expressed as percentage) across habitats.

| Subfamily |

Species across Forest types |

Acacia plantation |

Pine plantation |

Moist deciduous |

Dry deciduous |

Scrub jungles |

Semi evergreen forests |

Evergreen forests |

| Ponerinae |

Diacamma rugosm |

72.72 |

0 |

35.48 |

41.17 |

60 |

50 |

0 |

|

Harpegnathos saltator |

0 |

0 |

9.67 |

0 |

10 |

12.5 |

50 |

|

Leptogenys diminuta |

9.09 |

0 |

16.12 |

0 |

0 |

25 |

50 |

|

Leptogenys processionalis |

0 |

0 |

9.67 |

17.64 |

0 |

25 |

0 |

|

Leptogenys sp |

9.09 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Platythyrea parallela |

0 |

100 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Platythyrea sagei |

36.36 |

0 |

6.45 |

11.76 |

0 |

25 |

0 |

|

Pachycondyla henrie |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

30 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Pachycondyla luteipes |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

5.88 |

0 |

25 |

0 |

|

Pachycondyla rufipes |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

11.76 |

20 |

37.5 |

0 |

|

Pachycondyla tesserinoda |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Dolichoderinae |

Bothriomyrmex sp |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Dolichoderus sp |

9.09 |

100 |

6.45 |

11.76 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tapinoma sp |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Technomyrmex albipes |

9.09 |

0 |

9.67 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

| Formicinae |

Acantholepis sp |

0 |

0 |

6.45 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Acantholepis opaca |

0 |

0 |

12.90 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Anoplolepis longipes |

9.09 |

100 |

22.58 |

5.88 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Camponotus angusticollis |

27.27 |

0 |

32.25 |

11.76 |

0 |

75 |

0 |

|

Camponotus compressus |

27.27 |

100 |

54.83 |

52.94 |

40 |

25 |

0 |

|

Camponotus invidus |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Camponotus irritans |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Camponotus paria |

9.09 |

0 |

12.90 |

17.64 |

10 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Camponotus rufoglaucus |

9.09 |

0 |

22.58 |

23.52 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Camponotus sericeus |

9.09 |

100 |

32.25 |

58.82 |

50 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Camponotus sp |

18.18 |

0 |

0 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Camponotus(Colobopsis) sp |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Oecophylla smaragdina |

18.18 |

0 |

29.03 |

5.88 |

0 |

75 |

50 |

|

Paratrechina longicornis |

18.18 |

0 |

16.12 |

29.41 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

|

Paratrechina sp |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Polyrhachis mayri |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Polyrhachis rastellata |

0 |

0 |

29.03 |

5.88 |

20 |

50 |

100 |

|

Polyrhachis simplex |

9.09 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Polyrhachis tibialis |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Prenolepis sp |

0 |

0 |

6.45 |

11.76 |

0 |

12.5 |

0 |

| Myrmicinae |

Aphaenogaster beccari |

36.36 |

0 |

19.35 |

17.64 |

40 |

50 |

0 |

|

Cardicondyla sp |

18.18 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Cardiocondyla wroughtonii |

9.09 |

0 |

16.12 |

29.41 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Cataulacus taprobanae |

9.09 |

0 |

3.22 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Crematogaster nr dohrni |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster rothneyi |

9.09 |

0 |

9.67 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Crematogaster sp 1 |

36.36 |

0 |

29.03 |

41.17 |

20 |

25 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster sp 2 |

45.45 |

0 |

32.25 |

35.29 |

30 |

37.5 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster sp 3 |

36.36 |

0 |

3.22 |

5.88 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster sp 4 |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster sp 5 |

9.09 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Crematogaster sp 6 |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Crematogster wroughtoni |

0 |

0 |

9.67 |

17.64 |

60 |

12.5 |

100 |

|

Holcomyrmex sp |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Lophomyrmex quadrispinosa |

9.09 |

0 |

25.80 |

29.41 |

40 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Meranoplus bicolor |

18.18 |

0 |

6.45 |

5.88 |

10 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Monomorium dichroum |

9.09 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Monomorium floricola |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Monomorium gracillimum |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Monomorium indicum |

18.18 |

0 |

22.58 |

29.41 |

10 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Monomorium latinode |

0 |

0 |

9.67 |

17.64 |

0 |

0 |

50 |

|

Monomorium pharaonis |

0 |

0 |

6.45 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Monomorium scabriceps |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Monomorium sp 1 |

9.09 |

0 |

29.03 |

17.64 |

40 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Monomorium sp 2 |

0 |

0 |

12.90 |

0 |

20 |

25 |

0 |

|

Monomorium sp 3 |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Monomorium sp 4 |

0 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Myrmicaria brunnea |

0 |

0 |

29.03 |

17.64 |

30 |

25 |

0 |

|

Pheidole nr sharpi |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pheidole parva |

9.09 |

0 |

12.90 |

5.88 |

20 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pheidole sp 1 |

27.27 |

0 |

32.25 |

17.64 |

40 |

37.5 |

50 |

|

Pheidole sp 2 |

54.54 |

0 |

32.25 |

52.94 |

30 |

62.5 |

50 |

|

Pheidole sp 3 |

27.27 |

0 |

12.90 |

23.52 |

10 |

0 |

100 |

|

Pheidole spathifera |

9.09 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

20 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Pheidole watsoni |

9.09 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pheidole wood-masoni |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pheidologeton affinis |

18.18 |

100 |

3.221 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Pheidologeton diversus |

18.18 |

0 |

25.80 |

17.64 |

10 |

50 |

50 |

|

Recurvidris recurvispinosa |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5.88 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Solenopsis geminata |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium sp 1 |

9.09 |

0 |

25.80 |

35.29 |

20 |

37.5 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium sp 2 |

0 |

0 |

9.67 |

29.41 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium sp 3 |

9.09 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium sp 4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

11.76 |

0 |

37.5 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium sp 5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Tetramorium walshi |

9.09 |

0 |

3.22 |

11.76 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Pseudomyrmicinae |

Tetraponera aitkeni |

9.09 |

0 |

3.22 |

0 |

10 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Tetraponera nigra |

0 |

0 |

0 |

17.64 |

20 |

12.5 |

0 |

|

Tetraponera rufonigra |

18.18 |

0 |

12.90 |

5.88 |

10 |

25 |

0 |

75% of the recorded Formicines were present in dry deciduous forests (Figure 5) while 80% of them were found in moist deciduous but was overtaken by the Ponerinae subfamily. They were least represented in scrub jungles with 35% of the recorded species present. With the presence of arboreal species as Oecophylla and Polyrhachis, Formicines were dominant in moist deciduous forests. There was a mix of species that were both specific and generalistic with their food and niche requirements, and pushing them behind the Myrmicinae subfamily.

Ponerinae: Ponerinae subfamily was more specific about its niche requirements and food habits. The jumping ant H.saltator, an endemic species to the Western Ghats was highly specific about its food requirements. Field observations have revealed that 90% of the food, brought to the nest by these solitary foragers were flying insects as wasps, bees, and hoppers, other than which, they fed on termites, roaches and other ants. Spiders were one more of their favorite food but occasionally the ants did succumb to them. Their nesting sites were more specific, present always under overlapping canopy covers (recorded once in scrub jungles in the vicinity of moist deciduous forests) and were always absent from monocultures (Table 1). This was in strong contrast to the situation in places around Bangalore wherein H.saltator was recorded in Eucalyptus plantations (Ali 1991). They showed high dominance in moist deciduous, evergreen and semi evergreen forests. The other Ponerine, D.rugosm was extremely dominant in acacia plantations with 72.7% of the acacia plantations harboring this species (Table 2), making it a highly consistent species in acacia plantations. D.rugosm fed on other ants, spiders, roaches and termites. H.saltator fed on all most all of D.rugosm’s food and also had the ability to capture flying insects. Though both species were present in moist deciduous, semi evergreen and scrub jungles, the degree of overlapping in the sampled plots was as low as 5%, but overlapping was obvious in food niches. Both species preferred to nest in hard grainy soils. Nests of both species were never found in same plots. This suggests that the only reason for the non-existence of these two species together in an ecosystem is probably because the competition would be too fierce, which might result in removal of one of these species from the system. All three species of Pachycondyla were present in moist deciduous forests, while the entire genus of Pachycondyla was absent from evergreen forests (Table 1). The acacia and pine plantation record one species Platythyrea sagei and Platythyrea parallela each, respectively. Pachycondyla rufipes, a Ponerine, preferred small breaks in the forest for nesting purposes. These breaks were either due to logging or natural fall of old trees, resulting in a clearing in the forests. These ants were present in semi-evergreen, moist and dry deciduous forests. Foragers were recorded in scrub jungles only when moist deciduous forests were in vicinity. Nests of these species were absent from scrub jungles. The genus Leptogenys was absent from pine plantations and scrub jungles as well. They did not prefer open canopy areas. They were present in forests, which had dense canopy and thick leaf litter, wherein they are usually seen in long trails. Small foraging (five to eight individuals) hunting groups were also observed. An unidentified Leptogenys sp was found only in acacia plantations, often taking shelter under leaf debris. Termites seemed to be the chief diet of Leptogenys, along with their ability to attack and kill centipedes also.

Moist deciduous (90%) and semi evergreen forests (72%) had a high Ponerine species percentage (Figure 5). The species percentage reduced drastically in pine plantations (0.11%), acacia plantations (36%) and scrub jungles (36%). The specific niche and food requirement among Ponerines, along with their incompatibility with other Ponerines to be in same niches, arguably has resulted in less abundance and low species richness in the subfamily Ponerinae.

Dolichoderinae: Dolichoderinae was a very subdued subfamily in this region as compared to its stature in Australia wherein species of Iridomyrmex dominated the ant fauna (Anderson 1997). Also Dolichoderinae referred to be highly dominant all over the world presents a different scenario here. It was pushed behind with species of Tapinoma occurring only where human habitation was seen. It has been recorded in two samples, one a moist deciduous and the other a semi-evergreen forest (Table 1), both of which were under tremendous human stress. Tapinoma acts as an excellent indicator species to determine human interference (Viswanathan & Ajay 2000). The Formicine, A.longipes was absent in both these samples due to thick leaf litter and overlapping canopy cover present. Tapinoma has been recorded to tend to extra floral nectarines. Bothriomyrmex sp is recorded only from an evergreen forest. Technomyrmex albipes was dominant in acacia plantations and in moist deciduous forests and were absent from scrub jungles. Dolichoderus sp was absent from both semi evergreen and evergreen forests. They were however dominant in pine plantations.

All species of Dolichoderinae recorded have terrestrial nests. Dolichoderines had a highest species percentage in pine plantations (Figure 5), while 75% of them were present in moist deciduous forests.

Psuedomyrmicinae: Only one genus Tetraponera representing Pseudomyrmicinae has been recorded. These ants are solitary foragers and make their nests in fallen dead wood and rotten logs. They feed on insects. They were also retrieved from tuna fish and honey baits. Tetraponera was absent from pine plantations. T.nigra was dominant in dry deciduous forests. T.aitkeni was dominant in moist deciduous forests, while T.rufonigra was dominant in both moist deciduous forests and semi evergreen forests. Their absence from evergreen forests is possibly because of fewer samples. However, all three species were present in scrub jungle and in semi evergreen forests (Figure 5).

Community composition: The top four abundant genera, Pheidole, Crematogaster, Tetramorium and Monomorium, were not equally dominant in all the samples. They showed a lot of variation within forest types. An acacia plantation had a Pheidole and Crematogaster community; pine plantations had Pheidolegeton; moist deciduous forests had ant communities as Pheidole and Lophomyrmex; dry deciduous and scrub forests had a Crematogaster and Tetramorium ant community. The semi evergreen forests exhibited Pheidole and Tetramorium ant community; while in evergreen forests Pheidole and Monomorium ant communities were present. Dominancy of the two genera together was never seen in the samples. This meant that if one genus was dominant in one site, then the others either becomes a subordinate or in some instance would be absent from the system.

When the top four genera did not dominate and if the habitat was a dry deciduous or a scrub jungle, Lophomyrmex quadrispinosa suddenly dominate the region. In a moist deciduous forest, whenever the top four genera were not dominant, Myrmicaria brunnea and Pheidolegeton diversus were dominant. However, as mentioned earlier, both of them did not show dominancy in the same plots. M.brunnea had highly diverse feeding habits - both saccharine and meat lovers (bait traps) and are called as tropical climate specialists (Agosti et al. 2000). They dominated the system only when the top four genera did not. But however their dominancy was not spread to the plantations and scrubland. P.diversus had a much wider niche preference, as other than moist deciduous forests they also dominated in plantations, dry deciduous, scrub jungles and in semi evergreen forests.

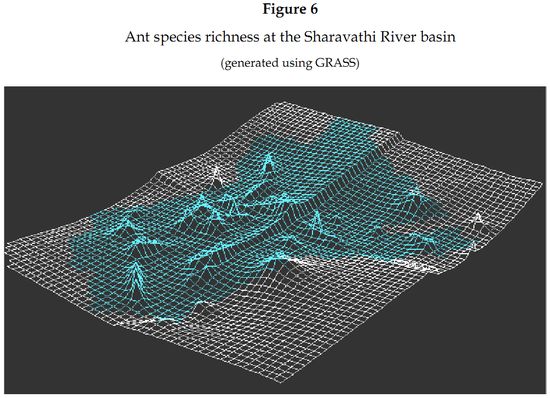

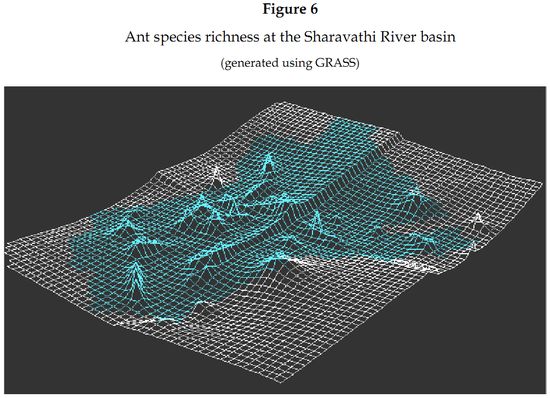

Ants along the radians: Radian 4 on the western side of the study area was the most species rich radian (Figure 6) recording fifty-seven species (67.85%) of ants. It was followed closely by radian 3, at the southern region, with fifty-one species (60.71%), radian 2 on the eastern region with forty-five species (54.21%) and then radian 1, towards the northern region, with twenty-six species (30.95%) of ants (Table 3).

|

Table 3: Ant composition (genera level) along the Radians

| Genera/Radians |

E |

S |

N |

W |

| Acantholepis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Anoplolepis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Aphaenogaster |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Bothriomyrmex |

|

|

|

+ |

| Camponotus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cardiocondyla |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cataulacus |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Crematogaster |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Diacamma |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Dolichoderus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Harpegnathos |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Holcomyrmex |

|

|

|

+ |

| Leptogenys |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Lophomyrmex |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Meranoplus |

|

+ |

|

+ |

| Monomorium |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Myrmicaria |

+ |

|

|

+ |

| Oecophylla |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Pachycondyla |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Paratrechina |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Pheidole |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Pheidolegeton |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Polyrhachis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Prenolepis |

+ |

|

|

|

| Recurvidris |

+ |

|

|

|

| Solenopsis |

|

|

|

+ |

| Tapinoma |

|

+ |

|

+ |

| Technomyrmex |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| Tetramorium |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Tetraponera |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Table 4: North Radian

| Genera/Distance from the reservoir (kms) |

0

1 |

4

2 |

| Acantholepis |

+ |

|

| Anoplolepis |

+ |

|

| Aphaenogaster |

|

|

| Bothriomyrmex |

|

|

| Camponotus |

+ |

+ |

| Cardiocondyla |

+ |

|

| Cataulacus |

|

|

| Crematogaster |

+ |

+ |

| Diacamma |

+ |

+ |

| Dolichoderus |

+ |

|

| Harpegnathos |

|

|

| Holcomyrmex |

|

|

| Leptogenys |

+ |

|

| Lophomyrmex |

+ |

|

| Meranoplus |

|

|

| Monomorium |

+ |

+ |

| Myrmicaria |

|

|

| Oecophylla |

+ |

|

| Pachycondyla |

|

+ |

| Paratrechina |

|

|

| Pheidole |

+ |

+ |

| Pheidolegeton |

+ |

|

| Polyrhachis |

+ |

|

| Prenolepis |

|

|

| Recurvidris |

|

|

| Solenopsis |

|

|

| Tapinoma |

|

|

| Technomyrmex |

|

|

| Tetramorium |

|

|

| Tetraponera |

|

+ |

|

At radian 1 (Table 4), most of the forest areas have been converted to acacia plantations. Acacia plantations had their own unique ant composition along with high percentage of D.rugosm. But truly arboreal ant taxa as Oecophylla were seen only in certain areas close to the reservoir (Table 5), where small patches of moist and dry deciduous forests still existed. However, these areas were under severe human stress exemplified by the dominancy of A.longipes in the dry deciduous forests. Moving further away from the reservoir, extensive acacia plantations areas were present, wherein D.rugosm dominated the ant fauna. As seen earlier, truly arboreal taxa were absent from plantations.

Along radian 2, ants of the genera Monomorium, Tetramorium, Crematogaster and Camponotus were present at all distances away from the reservoir (Table 5). The entire radian was under heavy human stress, with settlements and agricultural fields present close to the forest. Only the areas close to the reservoir were less disturbed, characterised with overlapping canopies and thick leaf litter for the entire radian. Harpegnathos, Leptogenys and Oecophylla are seen here. Pachycondyla, Lophomyrmex, Anoplolepis and Tapinoma were absent which suggests the kind of forest type present with reference to earlier discussions. Moving away from the reservoir, disappearance of Oecophylla and Harpegnathos is strongly related to the disappearance of continuous patches of moist deciduous and evergreen forests. Presence of Pachycondyla, as we moved away from the reservoir concretes the idea that evergreen forests were absent, but certain small patches of semievergreen, moist and dry deciduous forests with distinct canopy gaps were present, essential for the survival of this species. Moving closer towards the end of the catchment area, and away from the reservoir, A.longipes, D.rugosm, along with generalistic species as Pheidole, Myrmicaria, Monomorium and Tetramorium were present, suggesting large scale human interaction with the system.

Table 5: East Radian

| Genera/Distance from the reservoir (kms) |

0

1 |

4

2 |

8

3 |

12

4 |

16

5 |

20

6 |

24

7 |

|

| Acantholepis |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Anoplolepis |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

| Aphaenogaster |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

| Bothriomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Camponotus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cardiocondyla |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Cataulacus |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Crematogaster |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Diacamma |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Dolichoderus |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

| Harpegnathos |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Holcomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Leptogenys |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Lophomyrmex |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Meranoplus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Monomorium |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Myrmicaria |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Oecophylla |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Pachycondyla |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

| Paratrechina |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Pheidole |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

| Pheidolegeton |

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

| Polyrhachis |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

| Prenolepis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

| Recurvidris |

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

| Solenopsis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tapinoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Technomyrmex |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

| Tetramorium |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Tetraponera |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

Along the radian 3, a mix of acacia plantations and moist deciduous forests were present close to the reservoir. High levels of human interaction in forests revealed A.longipes, acacia plantations sheltered D.rugosm, while moist deciduous forests harbour Oecophylla (Table 6). Undisturbed forests present halfway along the radian, harboured Harpegnathos, along with truly arboreal taxa as Oecophylla and Polyrhachis. Due to obvious reasons, A,longipes was absent from the system. However, the undisturbed forests were not devoid of breaks that were revealed by the presence of Pachycondyla. However, towards the end of the catchment area, the ant composition of arboreal taxa along with Pachycondyla, Pheidole and Crematogaster coupled with the absence of A.longipes suggest the presence of moist and dry deciduous forests with a lesser degree of human stress on the system as compared to the second radian (Table 7).

Table 6: South Radian

| Genera/distance from the reservoir (kms) |

0 |

4 |

8 |

12 |

16 |

20 |

24 |

28 |

32 |

| Acantholepis |

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

| Anoplolepis |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aphaenogaster |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| Bothriomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Camponotus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cardiocondyla |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

| Cataulacus |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Crematogaster |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Diacamma |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

| Dolichoderus |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Harpegnathos |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

| Holcomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Leptogenys |

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| Lophomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Meranoplus |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| Monomorium |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Myrmicaria |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Oecophylla |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| Pachycondyla |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Paratrechina |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

| Pheidole |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Pheidolegeton |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| Polyrhachis |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

| Prenolepis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Recurvidris |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solenopsis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tapinoma |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Technomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

| Tetramorium |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tetraponera |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

Most prominent along radian 4, was the absence of Anoplolepis, which was because of less degree of human stress on the system along the entire radian. The absence of Ponerines for the first 16 km except Diacamma, suggests a different land feature compared to the other three radians (Table 7). Here the first 16km comprised of undulating barren hills and acacia plantations. This was characterised by the presence of Lophomyrmex, Camponotus and Meranoplus along the first half of the radian. Also, wherever acacia plantations were planted on the hills, Diacamma was extremely dominant. The only records of Solenopsis geminata and Holcomyrmex sp, on this radian suggested the presence of a new niche, the barren hills. Towards the latter part of the radian truly arboreal taxa as Oecophylla and Polyrhachis, Harpegnathos, Pachycondyla, Leptogenys were present, suggesting the presence of dense evergreen and semi evergreen forests. Also, the only records of Polyrhachis mayri were from these regions of radian 4 (west). However, towards the end of the catchment area, this radian was again under human influence confirmed by the presence of Tapinoma. But however, the human intrusion in the environment not being in huge proportions and also because of overlapping canopy areas with thick leaf litter, Anoplolepis longipes was still absent (Table 7).

Table 7: West radian

| Genera/Distance from the reservoir (kms) |

0 |

4 |

8 |

12 |

16 |

20 |

24 |

28 |

| Acantholepis |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Anoplolepis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Aphaenogaster |

|

+ |

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

| Bothriomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Camponotus |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Cardiocondyla |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Cataulacus |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Crematogaster |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Diacamma |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Dolichoderus |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Harpegnathos |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Holcomyrmex |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Leptogenys |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

|

| Lophomyrmex |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

|

| Meranoplus |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

| Monomorium |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Myrmicaria |

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

| Oecophylla |

|

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Pachycondyla |

|

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Paratrechina |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

| Pheidole |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Pheidolegeton |

+ |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Polyrhachis |

|

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

| Prenolepis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Recurvidris |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Solenopsis |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tapinoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

| Technomyrmex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tetramorium |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

| Tetraponera |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|