Results and Discussion

Buddhism’s role in promotion of medical

practice by the subaltern

South India came under Buddhist influence from

the time of Ashoka (3rd century BCE) with the

visit of Buddhist monks (arhats). Buddha Dharma

was propagated through monasteries and learning

centres and medical services were rendered from the

monasteries by knowledgeable monks. Buddhism80 M. D. Subash Chandran

found wide acceptability among the masses as it

opposed the oppressive caste system of Hindus,

as is evident from the Sangam Tamil works of

early centuries CE. Its decline from 7th century

started due to various reasons which weakened the

Buddhist Sanghas; the major reason was the revival

of Brahminism. However, despite its weakened state

Buddhism lingered in the south until the 14th century

(Murthy, 1987). As far as Kerala is concerned, Murthy

subscribes to the view that several temples bearing

the name Sattan-kavu and Aiyappan-kovil etc. which

exist to this day, were former Buddhist shrines. Sattan

(colloquial of Sastha?) was a name for Buddha and

kavu refers to a garden or a monastery. Hence Sattankavu refers to a monastery of Buddha (-ibid-). It is

well known today that the kavus of Kerala are worship

places. Kavus are exclusively sacred groves, or sacred

grove with small shrines or temples, or temples which

have lost their groves, as many are today (Chandran

et al., 1998).

Vaghbhta II, a Buddhist monk and one of the pillars

of Ayurveda, is believed to have lived in Kerala for

several years around 6-7th centuries CE (Sadasivan,

2000). Unique importance in Kerala, especially of

Ashtangahridaya, speaks of the influence of monastic

Buddhism in Kerala that time (Wolfgram, 2009).

The flourish of Sanskrit in Kerala, beginning in 5-6

centuries C.E. (Variar, 1985) coupled with social

emancipation credited to the spread of Buddhism,

could have conferred much advantage to its population

in learning Ayurvedic texts, where this classical

medical system became a living tradition. Valiathan,

himself an eminent physician and surgeon of the

allopathic system, and author of several works on

Ayurvedic history, endorses the view that Ayurveda in

Kerala got tremendous enrichment through ‘Buddhist

channels’ (http://textofvideo.nptel.iitm.ac.in) as given

in excerpts below:

● Ayruveda is practiced all over India whereas the

regional variation like Panchakarma is being

practiced in Kerala and Rajasthan only.

● Everybody had access to Ayurvedic ideas; there

are no restrictions; otherwise for initiation into

Ayurveda Brahmins were preferred; Khsatriyas

and Vaishyas were accepted; but Shudras were

not accepted. If they were accepted, they were

grudgingly accepted. For Buddhist there was no

restriction whatsoever; everybody was accepted.

● Sanskrit was taught to learners of Ayurveda;

there was no restriction in Sanskrit learning

through Buddhist channels. Regional languages

were also used.

● Pre-existing regional practices in healthcare,

were adopted into medical practice. Typical

local practices of Kerala adopted into Ayurveda

include: Dhara: Use of warm medicated oil on

body, Pizhichil: Using a cloth soaked in warm

medicated oil for massage, etc.

Ezhavas’ links with Buddhism, Sanskrit and

Ayurveda

Consistent with the teachings of Buddha the Buddhist

monasteries of the south had often dispensaries for

treating the sick. Kerala, nevertheless, is expected

to have a much older medical tradition of its own,

due to the richness of vegetation and the isolation

of the region from the rest of the country due to the

high rising Western Ghats to the east. The Ezhavas

constituting currently the largest Hindu community of

Kerala, are have their own medical tradition, although

their main traditional occupations were agriculture,

palm cultivation, toddy tapping etc. Introduction of

the concepts of Ayurveda, attributed to Vaghbhata,

would have immensely benefted the community, who

would have blended their own medical system with

that of Ayurveda. Buddhist Ayurveda itself had freely

absorbed local medical traditions from various parts

of the country. Sadasivan (2000) affrms that under

the patronage of Vaghbhata, Ashtangasamgraha and

Ashtangahridaya became the handbooks of Ezhava

physicians.From the shadows of legitimacy problems and prospects of folk healing in India 81

The decline of Buddhism from the south by 8th century

CE aggravated caste discrimination, a situation that

prevailed in Kerala for about the next 1000 years.

The inflexible laws governing social stratifcation in

Kerala never found expressions better than that of

Van Rheedeas recorded in the Preface to the Vol III of

Hortus Malabaricus composed in 1677:

This law (referring to social divisions)

“demands that everyone shall follow a special

mode of living by virtue of his birth, is observed

so rigorously, so strictly, and so scrupulously to

the present day that no mortal man could fnally

alter even a trifle of this law…. Thus farmers

and fsherman, through the whole course of the

years and the flight of time, will never beget

any but farmers and fsherman.”

At the same time one would wonder, how despite

such fatal laws governing caste system the Ezhavas

continued their medical profession and excelled in it.

Rheedes’ Preface has the answer:

Through this virtually fatal law, however,

no professions or crafts ever get lost, and all

peoples …. owing to the accident of their birth

…. are only occupied with those things to

which this fatal law through descent from their

ancestors has condemned them. And hence,

being rendered more and more capable through

this continuous instruction of their elders and

relations, they fnally acquire the striking and

exquisite knowledge of their profession…”

Itti Achudan, the Ezhava vaidyan who had the crucial

role in the composition of the botanical classic Hortus

Malabaricus explicitly states in his certifcate of 20th

April 1675 (printed in Hortus Vol I) that he was a

hereditary Malayali physician (Sampradayamulla

Malayalavaidyan) and the details of plants such

as ‘names, medical virtues, and properties of the

trees, plants, herbs, and convolvuluses’ narrated to

Emmanuel Carneiro, the interpreter were from ‘our

book’. Carneiro in turn termed the expression ‘our

book’ as the ‘famed book of the Malayalee physician’

(Heniger, 1980).

Historians of Kerala found numerous cases of

Ezhavas physicians of 18th and 19th to early 20th

century, known for their scholarship in Ayurveda

and Sanskrit. Despite the fatality of the caste

system in a feudal age and probable prohibition on

learning Sanskrit they made several contributions

towards development of Ayurveda in Kerala. Kerala

historian Gopalakrishnan (2000) states that the

Namboodiris (Kerala Brahmin caste) learnt medicine

from Buddhists. Expert Buddhists were converted

as Namboodiris as well. Through centuries Kerala

had numerous Ezhava families practicing medicine.

Some of the distinguished vaidyas were: Uppotu

Kannan (born 1825) is credited with the authorship of

Yogamritam, a popular work in Kerala based on the

same text in Sanskrit by Ashtavaidyans of Kerala. He

wrote an excellent exegesis for Ashatangahridaya.

His work Bhaskaram is a widely referred commentary

(Variar, 1985). Oushada Nighantu by Tayyil

Krishnan Vaidyan is another scholarly work. The 18th

century had about 300 celebrated Ezhava Ayurvedic

physicians; about 100 were court physicians during

18th and 19th centuries. Vaidyas from the Chavarkot

family of Kollam, were the chief Ayurvedic physicians

of the Travancore royal family during 18th and 19th

century, of whom Marthandam Vaidyan was specially

named. Cholayil Kunjmami Vaidyan was associated

with the Cochin royal family (Sadasivan, 2000).

Gopalakrishnan (2000) highlighted the important

role of Sanskritin mastering Ayurveda. It was widely

believed that the lower castes could not have gained

mastery in Ayurveda as they were not allowed to learn

Sanskrit. Malayalam scholar N.V. Krishna Warrier

(1989) tries to dispel this notion:

“it does not seem to be historically true to

equate Sanskritisation of South India as

Brahmanisation, as done by some. It was the

Baudhas and Jainas, who stood outside the82 M. D. Subash Chandran

purview of the varnasrama system that gave

leadership to the propagation of Sanskrit in

Ceylon and South India, and not Brahmins,

and they were not averse to give Sanskrit

education to non-Brahmins. Just as Sanskrit

was indispensable for Brahmins for the study of

Vedas and Vedantas, Sanskrit was required for

non-Brahmins to study result-oriented Sastras

like medicine, astrology and architecture.

Van Rheede on the rich biodiversity and

health care of the people of Malabar

During his journeys through Malabar (Kerala) during

the latter half of the 17th century Hendrik van Rheede,

the Dutch military offcer who became the Governor

of Cochin, could not help admiring biodiversity rich

landscapes and the good health of the people:

“On the way I observed large, lofty, and dense

forests …. they were pleasing through the

marvelous variety of the trees, which was so

great that it would be diffcult to fnd two trees

of the same kind in the same forest… I rather

frequently saw … many ivies of various kinds

clinging to one tree and moreover shooting

up in the very branches of the trees, and also

various plants against the bare trunk, so that

it was often very pleasant to see on one tree

displayed leaves, flowers and fruits of ten or

twelve different kinds… not only the fertile

soil extending in the plains was thus adorned,

but that even the rough rocks and the steeps

of the mountains were equally full of luxuriant

forests ” (Rheede’s Preface to vol. III of

Hortus).

On the good health of the people of Malabar, Rheede

remarked:

“They usually live to a very great age and their

health is cared for by native physicians, who

do not fetch medicaments from other regions,

or at all events as few as possible, since they

are content with only those medicaments

which their own region supplies bountifully, a

custom which is imitated with success by the

Europeans in those places.”

Rheede was critical on the practice of getting

medicines from Europe for the Dutch in Malabar:

“The Dutch, however, who are staying there

under the auspices of the East India Company,

indifferently use medicaments, which after

being fetched from those regions, are conveyed

via Persia and Arabia to Europe and thence

again by sea to India, in almost decayed and

spoiled condition, not without a waste of large

sums, which are spent without any advantage

on this matter…. Moreover it would involve

great proft for the Illustrious East India

Company, which indeed would be able to save

those expenses which it spends on transporting

medicaments”.

Hortus Malabaricus: A unique tribute to

Ezhava botany and medicine

Itti Achudan, an Ezhava physician of 17th century, had

played the key role in furnishing most of the valuable

data on 780 plant taxa (691 modern species) for the

compilation of Hortus Malabaricus by Van Rheede.

Three Konkani priest-physicians, Ranga Bhat,

Vinayaka Pandit and Appu Bhat, also supplemented

the information. A certifcate given by Achudan in

his own hand writing, attached to the Vol-I of Hortus

authenticated that the “disclosed the names, virtues

and properties of trees, plants, herbs and lianas as

they are written in our book and as I have observed

through long experience and practice”. Through his

contribution for this monumental work Achudan, not

only unraveled to the world the botanical treasure

of Malabar but also gave rare glimpses of the rich

knowledge of the Ezhava medical men on plant

diversity ranging from ferns to angiosperms, their

medical properties and uses. But for Achudan’s

participation the mission to compose Hortus,

would have been almost futile despite the effortsFrom the shadows of legitimacy problems and prospects of folk healing in India 83

of the Konkini vaidyas who gave more of textual

knowledge based on their Ayurvedic text MahaNighantu or Great Lexicon. The 12 volumes Hortus,

in Latin, were published between 1679-1692. Hortus,

became an important pre-Linnaean classical botanical

composition in Latin. Its translation into English was

published in 2003 by K.S. Manilal.

Hortus Malabaricus is considered as the earliest

example of systematic scientifc documentation of

folk medicinal practices of intangible heritage from

anywhere in Asia. It is the oldest comprehensive

printed book on the natural plant wealth of Asia,

compiled and published in Latin by Van Rheede.

This 12-volume treatise, contains illustrations of

742 plants from 691 modern species, together with

their descriptions and medicinal and other uses. It is

perhaps the only authentic evidence of the ancient

ethno-medical knowledge of Kerala, and that too

culled out from the hereditary palm-leaf manuscripts

of Itty Achudan. Whereas the Konkini Brahmin

collaborators depended on an Ayurvedic Nighantu

for the plant names, Achudan “disclosed the names,

virtues and properties of trees, plants, herbs and lianas

as they are written in our book and as I have observed

through long experience and practice” (quote from

his certifcate in Vol. 1). Professor Manilal, from the

University of Calicut, who has studied the various

aspects of the original book for more than 40 years,

wrote the English translation (in 2003) about 325

years after the publication of Vol. I in Latin in 1678.

In the words of Mohan Ram (2005):

“The work describes plants with multiple uses

as well as with medicinal properties. It includes

modes of preparation and application, based

on pre-Ayurvedic knowledge of the ancient,

renowned, hereditary physicians of Malabar.

The ethnomedical information presented in

Hortus Malabaricus was culled from palm

leaf manuscripts by Itty Achudan, a famous

physician of Malabar at that time.”

Achudan Vaidya: underplay of a

pre-Linnaean legend

For the frst time in Kerala’s history, Achudan’s

certifcate in the extinct Kolezuthu script of Malayalam

Hortus became the frst document to be printed in the

world in that language, along with its rewriting in

modern Aryaezuthu script. This certifcate, apparently,

was included more for the purpose of silencing his

critics, by van Rheede, more of a military person

than a botanist or ethnobiologist, whose credential

for authorship of the monumental Hortus was not

convincing for contemporary scientists. He was, in

the words of Fournier (1980), “no great botanist….

Not knowing the frst thing about systematic botany”,

but was a ‘successful organiser, who was able to bring

together the people who could realize his plans’.

Nevertheless, Rheede set high standard for his work

and achieved the same, making Hortus ‘the most

important and reliable source on the flora of Malabar,

indeed until the end of the eighteenth century, on the

flora of the whole of India’.

Rheede would have instructed his collaborators,

including the Konkini Brahmins, regarding the

contents of certifcates to be given by them for

Hortus, mainly to defne their specifc contributions

for the project, as a formal authentication, probably

needed for approval of his work by the biologists

in Europe. Achudan’s document mentions his

profession as vaidyan, his lineage, address and stated

unambiguously the certifcate was given mainly

to dispel the doubts of the people concerned, about

his role in the book project. Having served such a

purpose of authentication, except for the elaborate

description of Malabar, its flora, society and about

the methodology of work with the help of native

physicians, in the Vol. III of Hortus, nowhere else

occurs any acknowledgement towards the local

physicians, including the attribution of species to their

respective individual credits. Instead, volume after

volume of Hortus contained prefaces and profuse84 M. D. Subash Chandran

statements of dedication to honorable members of

the Dutch aristocracy, dukes and barons, which is

uncommon to scientifc writing.

Rheede, though underplayed the specifc role of

Achudan, in his Preface to Vol. III describes the

excellence of botanical knowledge the low caste

vaidyas had accumulated through “continuous

instruction of their elders and relations” so that “they

fnally acquire the striking and exquisite knowledge

of their profession which they now display.” Perhaps

through “accident of birth” these local men were

to perform their duties “with a more than stoic

inevitability”. Rheede seems to have taken for granted

this fatalism associated with lower castes of Malabar,

and with his passing remarks and affxation of the

necessary certifcates of authentication, implying

data has been obtained through ‘order’ (the term

‘order’ is explicit in Achudan’s certifcate). Beyond

that the providers of data did not merit any further

commendation from Rheede, a fact reflected in the

commentary of Heniger (1980) “Although the twelve

impressive folio volumes of the Hortus Malabaricus

are due to the exertions of his scholarly and skillful

collaborators, with the Preface Van Reede has earned

for himself a place in the history of tropical botany.”

In the Preface to the third volume Rheede admits that

the frst two volumes had met with a good deal of

criticism, including what justifed him in having his

own name printed, as the frst author, on the title page.

Most impressive contribution towards popularizing

the greatness of Malabar botany is through the English

translations of Hortus with annotations and use of

modern botanical nomenclature by K. S. Manilal,

published by University of Kerala in 2003. Manilal

(1980) had already shown greater sense of certainty

as regards the role of Achudan “who provided most

of the information regarding the medicinal power of

the plants described in Hortus Malabaricus,” based

on local medicine and Ayurvedic medical practice as

contained in his family book. One could only wonder

why a European like van Rheede had to take all such

trouble regarding publicizing the works of indigenous

botanists of the time when it was in his ambit of power

to execute things by order alone. Indeed, the Rajas

of Cochin had the onus of preserving the heritage of

Itti Achudan or his like, including his precious family

texts and the Great Lexicon (Maha-Nighantu) used

by the Konkini Brahmins. Manilal’s search for these

valuable indigenous medical texts for about 18 years,

after the passage of over three centuries since Hortus

publication, went futile, as nothing remained of them.

Considering the indifference of the Cochin rulers

towards these matters rich tributes need to be paid

Van Rheede’s great efforts, immortalizing Achuden

and other vaidyas of the time through the 12 volumes

of Hortus. Notably, An Interpretation of Van Rheede’s

Hortus Malabaricus published by Nicolson et al.

(2008) in Regnum Vegetabile, Vol 119, was acclaimed

as the only book by Indian authors published in this

series till date and considered a classic, ‘essential for

any study on the taxonomy of South Asian and South

East Asian plants’.

The Malayalam binomial nomenclature

The robustness of classifcation of plants by Ezhava

physicians, of the time is very well reflected in

the nomenclature itself, which may be termed

a pre-Linnaen binomial in the reverse order

(species equivalent preceding genus equivalent).

Environmental historian Richard Grove (1995)

reflects on the matter (Grove also had personal

discussions with this author on ‘Ezhava botany’

during his visit to Uttara Kannada, and on earlier

occasions):

“Most important for the subsequent history

of tropical botany, the insight of the Ezhavas

into the affnities among a large number of

plants in the Hortus malabaricus are revealed

by the names they gave to those species which

have the same stem and to which one or more

prefxes are added: for example Onapu, Valli-

onapu and Tsjeri-onapu. The names also

give us a considerable amount of incidental

sociological material. For Onapu, Onam is the

harvest festival in which this particular flower

would be used. The names thus preserve the

true social affnities of the plant name instead

of isolating them in a contextless arbitrary

category, as well as probably allowing a

truer affnity in terms of pharmacological

properties.”

The respect of the pre-Linnaean European systematic botanists, towards the Ezhava system of classifcation, has been highlighted by Grove (1995). Arnold Syen and Jan Commelin, while arranging the

sequence of plants in Hortus Malabaricus, retained

the order of sequence which the Ezhavas followed on

the assumption of their relationships “even if the Europeans knew this to be contrary to their own classifcation system.” Linnaeus, in particular, in 1740, fully

adopted the Ezhava classifcation and affnities in establishing 240 entirely new species as did Adanson,

Jussieau, Dennstedt, Haskarl, Roxburgh, Buchanan

and Hooker (-ibid-).

After closely examining the Malayalam nomenclature

of plants in the Hortus, especially used by the Ezhavas

(presumably from the family texts of Itti Achuthan), it

is not unreasonable to postulate that Linnaeus, known

as Father of Botany, who published his monumental

work Species Plantarum, in 1753, 75 years after

publication of the frst volume of Hortus Malabaricus

was influenced by the Ezhava system of nomenclature

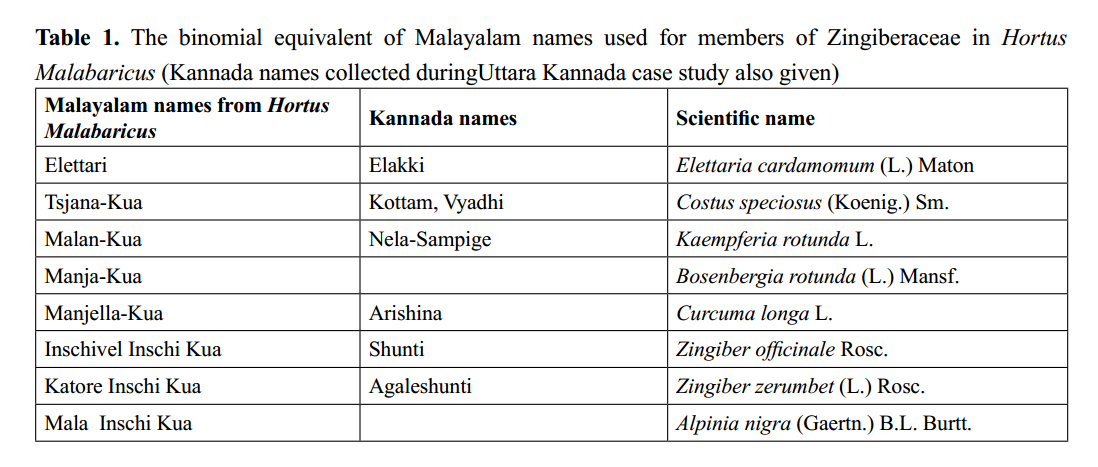

of plants. The very look at Achudan’s system of

naming of the closely related members of the ginger

family Zingiberaceae (Table-1) is contemplative

and reflective of the botany and relationships of

the plants concerned. Usually a typical taxon of the

related species is given a single name (the stem of

the name); for instance eg. Alpam (Apama siliqosa

Lam.; Champacam = Michelia champaca L., Manga

= Mangifera indica L. etc.) In the case cited in detail

as in Table-1, cardamom is called Elettari (as in

Hortus) its normal Malayalam name, designated as

Elettaria cardamomum by Linnaeus. All the other

Zingibers have in the Hortus the stem of the name as

‘Kua’, which is equivalent of genus. The others of the

ginger family are designated as Tsjana-Kua, MalanKua, Manja-Kua, Manjella-Kua, InschivelInschiKua, KatoreInschi-Kua etc. The last two names have

attachments that sound like sub-species (Inschivel and

Inschi). Obviously European biologists, of the colonial

period, placed at the summits of wealth biological

materials from all parts of the planet, and with their

linguistic superiority and managerial skills had greater

advantage, in formulating the globally accepted

binomial nomenclature, unlike the indigenous

Ezhavas, socially oppressed and for centuries

not allowed to use anything beyond the primitive

Kolezethu Malayalam and ‘smuggled Sanskrit’

learnt through the informal kudi-pallikootams (home

schools) run by Asans. The script and caste went

together in Malayalam, Kolezethu for lower castes

and Aryaezuthu (meaning ‘script of nobles’) for upper

castes. From early 19th century Kolezethu fadedaway

with the British universalizing education through

the government schools, and also through the Basel

Mission schools founded by German missionaries. It

is likely that texts of Achudan, in palm leaf bundles,

having perhaps no successors to follow him, would

have turned redundant and undecipherable, leading to

neglect and loss with the passage of time. Whereas

Achudan’s saga was immortalized through Hortus

by Van Rheede, rest of the subaltern knowledge on

traditional medicine in Kerala would have faded

away with time due to loss of manuscripts, lack of

successors and the Indian Medical Acts of later times

denying legitimacy for persons practicing without

approved qualifcations and registration. Retrieval,

scrutiny and legitimization of centuries old medical

knowledge, still lying dormant in the attics of old

houses in palm leaf manuscripts, or through family

lineages in the cases of hereditary vaidyan, using clues

through the Peoples Biodiversity Registers (Kerala is

most successful in the country for PBRs completed,

in almost every panchayat, under the guidance of one

of the most active State Biodiversity Boards) might

lead to new vistas of traditional medical knowledge.

The Uttara Kannada Study of

Folk Healers

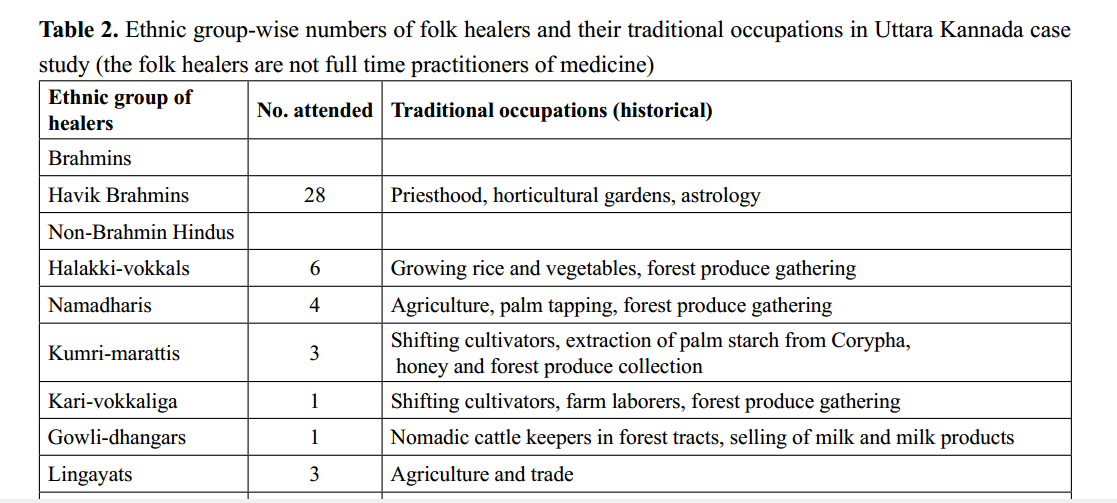

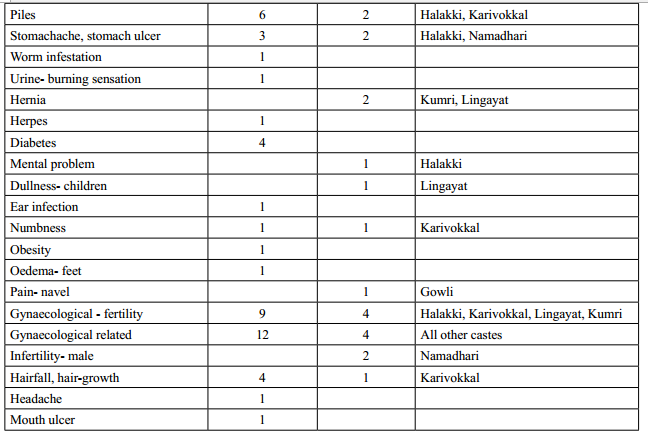

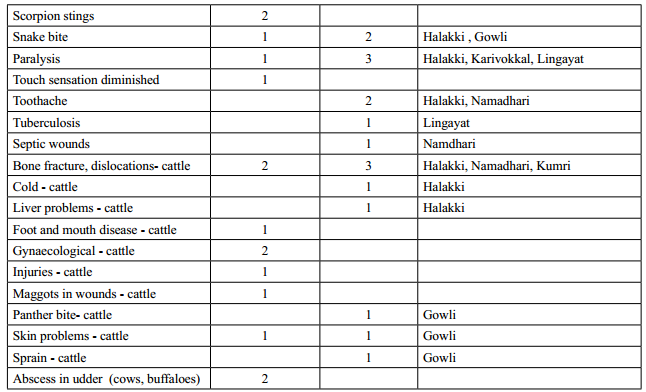

The kind of diseases and other health related

contingencies treated by 46 healers were recorded

and details of the medicines prepared kept in the safe

custody of the Karnataka Biodiversity Board. All the

persons, from diverse ethnic groups, who voluntarily

attended the traditional knowledge documentation

programme belonged to the Hindus. The details

regarding the number of persons attended, ethnic

group-wise and their traditional occupations are given

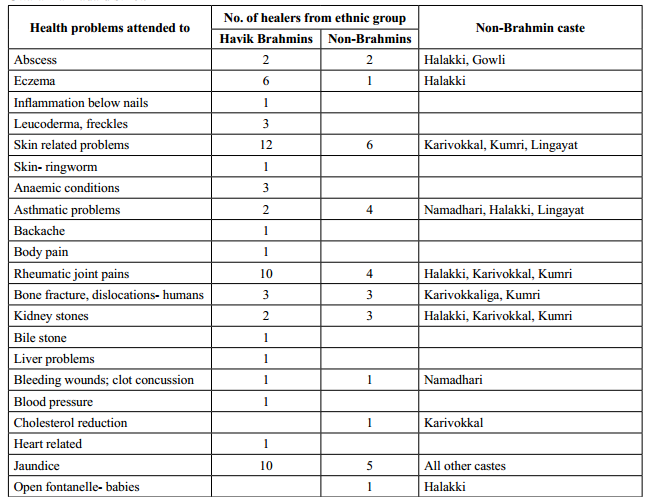

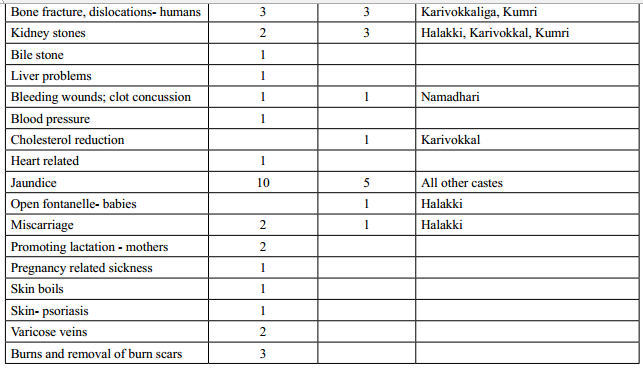

in the Table-2. The type of health problems which the

healers claimed expertise in treating, using locally

made herbal formulations are given in Table-3.

Of the folk healers interviewed Havik Brahmins (28)

outnumbered all the non-Brahmin ethnic groups (18).

This has no correlation however with the district’s

population structure. The Havik Brahmins constitute

an illustrious group of the population in the district

given to primarily pursuits like priesthood and

horticulture. They are traditional experts in raising

multi-storied gardens with arecanut, coconut, black

pepper, betel vines, nutmeg, cardamom etc. in the

valleys of Western Ghats. The farming section of

Haviks, in general, combines hard physical work

with several intellectual pursuits. Members of the

Table 3. Details of folk healers interviewed and kind of health problems attended to during a sample study in

Uttara Kannada district

community have good levels of education and many,

well versed in scriptures, offciate as priests for almost

all Hindu castes, unlike most other Brahmins. Their

rustic traditional homes, blending with the evergreen

forests around, have such home gardens, which at the

outset appear like domesticated wilderness, but are

composed of ornamentals, vegetables, nutraceutical

and medicinal plants as well as of semi-wild and

wild fruit trees like pickle mango varieties, Garcinia,

Artocarpus lakoocha (Vate-huli), jamuns, etc.

Many Havik Brahmins, render yeoman services to

the community around through healing and health

counseling. The vaidyas interviewed, though are

not qualifed to practice legally, render almost free

medical services using herbal medicines. They have

sound knowledge of the nutraceutical importance of

even weeds and wild plants, compared to most others

interviewed. Some of the distinguished practitioners

of herbal medicines have epistemological approach

to herbal cure, probably based on generations of

keen observations as well as under the influence of

Ayurveda. Such approach have made them confdent

in dealing with patients suffering from cancers,

bile stones, burn scars etc. However, for conclusive

proof on the effcacy of their treatments interviewing

patients is essential.

Of the non-Brahmin healers were few persons from

Halakki-vokkals, a community of small scale farmers

growing rice and vegetables, the latter mainly for

sale. They are well known as traditional healers

and some of them like the Halakki-vokkal vaidyas

of Belamber in Ankolataluk of the district earned

good name for treating paralysis. Other community

vaidyas who volunteered to attend the documentation

programme were in small numbers and therefore all

of them are grouped under non-Brahmin vaidyas.

Table-3 provides comprehensive picture on the array

of health problems which these traditional healers

have been handling. In a district like Uttara Kannada,

full of forests and rugged terrain, and the states’

inability to provide decent healthcare in the interior

places the local healers had entrenched themselves as

inevitable components of the society. As connectivity

is on the increase, and with greater spread of

education the sway of biomedicine and Ayurveda is

on the rise. Most vaidyas are elderly people and their

children tend to leave their homes after education, in

search of better prospects of employment elsewhere.

The vaidyas themselves are losing interest for fear

of punitive action from authorities as they are still

outside the realm of legitimacy.

Legitimacy of traditional medical knowledge

and unlawful practitioners

With the establishment British East India Company

itself, European medicine came to be looked upon as

the dominant knowledge system. By mid-19th century

the British offcial colonial policy marginalized

indigenous medicine to secondary status. After

the Indian Mutiny in 1857 the government was

careful not to disturb the local sensitivity around

the traditional treatments and restrained from the

process of annihilation of vaidyas or hakims through

registration of only modern medical practitioners. If

the conditions were not hostile the British Government

would have had its way, and indigenous systems like

Ayurveda, Unani etc. “would have been buried in the

nineteenth century itself” (Harrison, 1994). Later, as

the Indian Medical Service started accepting Indian

nationals, students from upper classes and minorities

entered medical colleges and European medicine

became the offcial health care system (https://www.

ncbs.res.in/History Science Society/home). The

Medical Council of India established in 1934 under

the IMC Act, 1933 repealed and enacted again the

Indian Medical Council (IMC) Act in 1956. People

qualifed from recognized medical institutions and

colleges were only allowed to practice. The Indian

Medicine Central Council Act, 1970 has been the most

detrimental to traditional physicians of codifed and

non-codifed systems of Indian medicine, as the Act

stipulated that a practitioner of Indian medicine who

possesses a recognised medical qualifcation and is

enrolled on a State Register or the Central Register of

Indian Medicine, (Ashtang Ayurveda, Siddha or Unani

Tibb) shall only practice. An estimated one and a half

million providers of folk medicine, who do not have a

certifed medical degree, but who provide health care

to nine hundred million Indians living in rural areas

(Hardiman and Mukharji, 2012) have been affected by

such stringent legislation. Bode and Hariramamurthy

(2014) estimate two million as the number of local

herbal healers, whose healing services to the Indian

society are affected, because of their ‘semi-legal

status’ aggressive marketing of biomedical drugs, and

biomedicine’s social prestige.

Case studies from various parts of India reveal that

the non-codifed TK is not getting adequate protection

from exploitation. For instance, about 200 medicinal

plants from Chittoor and Nellore districts of Andhra

Pradesh, being used by communities like Yanadis

have been developed into modern medicines without

any recognition or reward for any indigenous person

(Vedavathi, 2013). The Yanadis feel that priority

should be given to formal recognition of their TK and

exclusive rights to use the bioresources needed for

sustaining their knowledge/practices. Just as in Uttara

Kannada the Yanadi youth are also not interested in

TK, including traditional medicine.

The compulsion for acquiring a degree or diploma in

the concerned discipline of Indian medicine sounded the

death knell for both traditional, hereditary practitioners

of codifed Indian medicine as well as of the more

informal folk medicine, irrespective of the caste or

community. The traditional forms of Ayurveda and its

dwindling number of practitioners are fast disappearing

giving way to graduates from modern Ayurvedic

colleges, and their ways of preparing remedies have

been overtaken by the large scale production units run

by the thriving pharmaceutical industry (Warrier, 2016).

Menon and Spudich’s (2010) insightful study reflects

the predicament of senior Ashtavaidya physicians of

Kerala, who were masters of healing practiced for

more than 40 years. The desperation embodied in the

feelings of Vaidyamadham Namboodiri that “We lived

and breathed Ayurveda from birth” is because of the

sense of futility despite long years of training, intense

study and apprenticeship in the Gurukulam system

under accomplished masters, covering subjects

ranging from even grammar, poetry and drama in

addition to mastering Sanskrit works on Tarka (the

rules of reasoning and argument), and the traditional

philosophies of Nyaya, Vaisheshika and Samkhya

– all necessary to gain profoundness in the feld of

Ayurveda. Another Ashtavaidyan also testifed:

“Five years of textual study, fve years of learning

about medicinal plants in the forest, and fve years

of apprenticeship at home,” –including identifcation

of medicinal plants and making of personalized

medicinal preparations amounted to, in the eyes of the

State, nothing short of quackery. The Ashtavaidyas felt

the kind of training and studies that they underwent

cannot be sustained in the contemporary environment

of new trends in Ayurveda practice and teaching,

involving many modifcations which undermine the

very nature of Ayurveda (Menon and Spudich, 2010).

However, in these interviews the Ashtavaidyas were

well acquainted with the present-day Ayurveda

educational system and their younger generation rose

to the occasion to carry forth the legacy by getting

trained in modern Ayurvedic colleges.

|