|

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

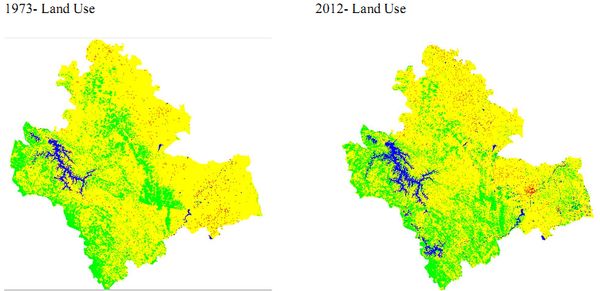

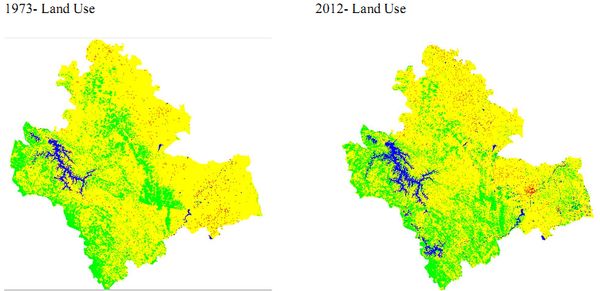

The administration of the Forest Department in the district is under the charge of the Conservator of Forests, Shimoga Circle, Shimoga. The district has been divided into three Forest Divisions, namely, Shimoga, Bhadravati and Sagar Divisions.The forests of the district, which yield rich and valuable products, covered an area of 4, 34,516 hectares nearly 40.27 % of the land in the district. The areas of different types of Forests are as follows: Evergreen forests- 69,459 hectares (16%), Semi-evergreen- 88,135 hectares (20.28%), Moist deciduous- 1, 30,612 hectares (30.06%), Dry deciduous -1, 09,539 hectares (25.21%) and Scrub Forests-24,111 hectares (5.55%). Vegetation cover of the study area was analyzed through NDVI. Figure 2 and table 1 illustrates that area under vegetation has declined from 96.57% (in 1973) to 91.72% (in 2012). Land use analysis for the period 1973 to 2012 has been done using Gaussian maximum likelihood classifier and the temporal land use details are given in table 2. Figure 3 provides the land use in the region during the study period. There has been 1.47 % growth in built up area during last four decades with the decline of vegetation by 2.6 %.

Figure 2: Land Cover changes from 1973 to 2012

Table 1: Land Cover statistics

| Land Cover (%) |

| |

Vegetation |

Non-Vegetation |

| 1973 |

96.57 |

3.43 |

| 2012 |

91.72 |

8.28 |

Figure 3: Land Use changes in Shimoga District

Table 2: Temporal land use dynamics

| Land Use (%) |

| |

Urban |

Vegetation |

Water |

Others |

| 1973 |

0.66 |

23.88 |

1.91 |

73.61 |

| 2012 |

2.13 |

21.28 |

3.09 |

73.63 |

Case studies on two Kan forests of Thirthahalli Taluk

Kurnimakki-HalmahishiKan and Kullundekan in the Taluk of Thirthahalli, Shimoga district was studied in the month of April 2012, mainly from the vegetation angle and for knowledge of threats facing it.The Kurnimakki-Halmahishi Kan is said to be about 1000 hectares and KullundeKan covers an area of 453.86 hectares. These are not a single piece but distributed in several survey nos. There is considerable confusion on the demarcation of the boundaries of the Kan due to encroachments, conflicting Claims of ownership and other practical problems.Shimoga and Chikmaglur districts were part of erstwhile Mysore state. Kan lands were recognized by state Forest department till almost 1970. But after that those survey numbers were merged in reserved Forests and other kind of forests including minor forests, State forests and District forests. Evergreen to semi-evergreen forests and secondary moist deciduous forests were the main forest types present in these Kans.

Fragmentation of vegetation: The Kan forests were praised in the past for their unique evergreen vegetation of lofty trees, rich moldy soils, fire security, as source of perennial streams and production of various products in demand for human subsistence, especially as centers of pepper production. Today a close look at the Kurnimakki-Halmahishi Kan on the ground or using aerial imageries, reveal a high degree of forest fragmentation. The composition of the landscape elements of the Kan does not conform to the past descriptions of such sacred forests from Central Western Ghats. It appears that many a stream originating in the Kan get dried up in the summer months resulting in abandonment of minor tanks constructed along their courses, thus obviously, with adverse consequences on farming downstream and water-flow into the Thunga River diminished. Such severe human induced changes in the evergreen forests of Western Ghats are bound to have cascading consequences on human welfare in the Deccan plains mainly because of reduced water flow in the east-flowing rivers.

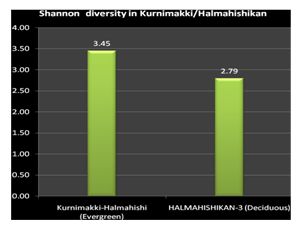

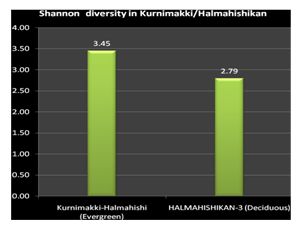

Tree species in evergreen-semi evergreen forest type: Evergreen trees of 25-30 mheight were numerous in the forest and belonged to species such as Aphanantha cuspidate, Canarium strictum, Mangifera indica, Syzygium hemisphericum, Syzygium travancoricum etc. Evergreen trees of the second level of general heights from 15-25 m include Actinodaphne hookeri, Aglaia roxburghiana, Anthocephalus kadamba, Beilsmeida fagifolia, Dimocarpus longan, Ficus callosa, Holigarna ferruginea, Hopea ponga, Olea dioica, Syzygium cumini etc. Deciduous species like Careya arboa, Lagerstroemia microcarpa, Stereospermum personatum, Terminalia paniculata, Terminalia bellirica, Vitex altissima, Xylia xylocarpa, Zanthoxylum rhetsaetc. The secondary deciduous forests within the Kan and their peripheral areas are obviously due to forest fragmentation through cutting and burning. Altogether 46 species in evergreen and 25 tree species were found in deciduous forest of Kurnimakki-Halmahishi Kan. In Kullunde Kan, a part of it was cleared and was with coffee plantation had 21 tree species. Another coffee planted area had 19 species, whereas the deciduous forest had least number (7). The Shannon diversity index for trees was found to be higher (3.45) for the evergreen dominated patches than for the deciduous (2.79) in Kurnimakki-HalmahishiKan (figure 4).

Figure 4: Shannon diversity index for evergreen dominated and deciduous dominated areas in Kurnimakki-Halmahishi Kan

In case of KullundeKan, Diversity index (Shannon diversity) for tree species for the evergreen forest was highest at 3.11, for the forest patch allotted to private person and protected as such (figure 5). When a climax evergreen forest of Dipterocarpusindicusand Calophyllumtomentosumdomination was partially cleared and planted with coffee, despite the isolated towering trees remaining, the diversity index was lower at 2.75. Yet another portion with coffee had reasonably good number of species, although they were of secondary nature and smaller in stature with diversity index at 2.87. The lowest diversity of 1.85 was for the secondary moist deciduous forest.

Figure 5: Shannon diversity index for tree species in four categories of forests, with the intact preserved forest in malki land showing marginally higher diversityin Kullunde Kan

Swamps with Syzigium travancoricum: In some of the swampy water bodies associated with the Kan we could see small populations of Syzigium travancoricum, an evergreen endemic tree of the Western Ghats, which has been red listed as critically endangered by the IUCN. Discovery of this majestic tree in the Kurnimakki-Halmahishikan, new report of such a species from Shimoga district itself, underscores the importance of preservation of Kans as Heritage sites from cultural, biological angles. Its rare occurrence associated with swampy places in some of the evergreen Kan forests of Ankola and Siddapur, 700km north of Travancore came as surprise, while this finding highlights the role of Kans as centres of biodiversity conservation in otherwise human impacted landscapes (Chandran et al., 2008).

Sacred Kan on the wane: The Kan forests of Central Western Ghats were important natural sacred sites and cultural centres of the pre-British village communities. At one time, they rose majestically in the horizons, covering large areas in the high places of the malnadu village landscapes, surrounded by cultivations, timber rich secondary forests, and savannized grazing areas. Perennial streams gushing out of these sacred forests were often embanked to make irrigation tanks. Unfortunately, the Kans did not merit consideration as sacred places of village communities under the British rule and so after independence. In Shimoga district, particularly, many kans were brought under the jurisdiction of the revenue department, which allotted Kan lands for meeting various non-forestry purposes such as for growing coffee, expansion of cultivation, for grazing purposes and numerous others, neglecting the rare species they conserved and also of their crucial hydrological importance. The Government also conceded large portions of Kans on long leases to the Mysore Paper Mills for growing industrial woods like Eucalyptus and Acacia sp. after clearing the natural vegetation.

|