Centre for Sustainable Technologies,Centre for infrastructure, Sustainable Transportation and Urban Planning,

Energy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012, India Introduction The Molluscs are soft bodied invertebrates with or without an external protective shell. They inhabit usually water bodies, marine, estuarine, as well as fresh water; many are also terrestrial, often associated with moist shaded lands. If the body of the Molluscan taxa is enclosed by a pair of shells hinged in the middle it can be classified under the Class Bivalvia. Bivalves, which include clams and oysters contribute to the livelihoods of many people in India. The first Mollusc appeared at the end of the Pre-Cambrian period, approximately 550 million years ago (Sturm et al., 2006). It is the second largest phylum in the invertebrates comprising more than 100,000 species worldwide of which, 5070 species are present in India (Venkataraman and Wafar, 2005). Molluscs have been exploited worldwide for food, ornamentation, pearls, lime, and medicine (Nayar and Rao, 1985). Geologic evidence from South Africa indicates that systematic human exploitation of marine resources had started about 70,000 to 60,000 years ago (Volman, 1978). Of the 5070 species of molluscs recorded from India, very few of them, especially of the bivalves, are exploited for food and other economic purposes. Three clam genera, Meretrix, Paphia and Villorita, and some oysters are used as food and sustain the livelihoods scores of people in the estuarine villages of the Karnataka (Rao and Rao, 1985; Rao et al., 1989; Boominathan et al., 2008). Even these few edible bivalves are threatened in recent times due to shell and sand mining, over-exploitation, and salinity changes brought about in the estuaries due to constant releases of fresh water from hydroelectric projects upstream in the rivers. Earlier study in Kali estuary (Boominathan et al., 2012) revealed that the edible estuarine bivalves lost about 15 km of their occupational territory, pushed more westwards towards the Arabian Sea, due to water releases from upstream dams. This necessitated similar studies in all the estuaries of Uttara Kannada, which are getting subjected to ever increasing human pressures. The present study covered the situation of the edible bivalves, their diversity and its distribution, in Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavathi estuarine areas.

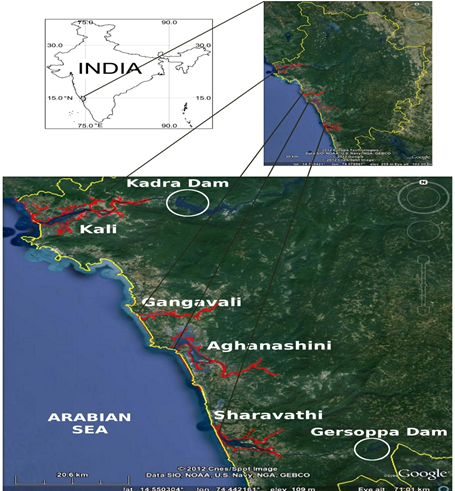

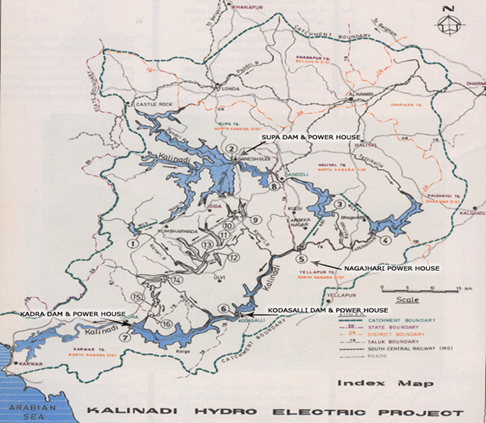

Figure 1.1: Estuaries of Uttara Kannada District viz. Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavathi. Uttara Kannada Estuaries The Uttara Kannada District has four major estuaries viz. Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavathi (Figure 1.1). The Kali estuary is located in the northern most part of the district, the Bedthi or Gangavali about 32 km south from Kali river-mouth, the Aghanashini or Tadri estuary, about 10 km south of Gangavali, and the Sharavathi estuary is about 24 km south of the Aghanashini estuarine mouth Kali Estuary: The Kalinadi originates near the village Diggi in the Joida taluk of Uttara Kannada, and has many tributaries. It is also known as Karihole and as Dagi in its upper reaches. Its total length is 184 km and meets the sea, three km north of Karwar. It has four major dams with hydroelectric power stations viz. Supa, Nagjhari power house, Kodashalli, and Kadra (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: Kali River with Dams.

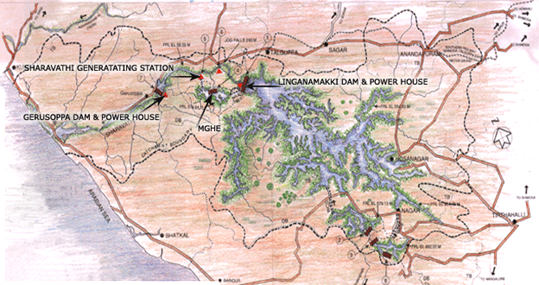

Figure 1.3: Sharavathi River with dams

Livelihood Resources - Edible Bivalves of Uttara Kannada Estuaries There are six edible clams, viz. Anadara granosa, Meretrix casta, Meretrix meretrix, Paphia malabarica, Polymesoda erosa, Villorita cyprinoides and some oysters present in all the estuaries of Uttara Kannada district (table 1), except in Sharavathi estuary where only one clam Polymesoda erosa occurs today and the oysters can be seen on rocks close to the river mouth with higher salinity. Among these edible bivalves the genus Meretrix, Paphia, and Villorita, and oysters contributes to the livelihoods of many peoples (Rao and Rao, 1985; Rao et al., 1989; Boominathan et al., 2008). Table 1: Edible Bivales of Uttara Kannada estuaries. P = Present, A = Absent.

Anadara granosa is present in all the estuaries except, Sharavathi. The distribution of A. granosa is restricted to one kilometer range from river-mouth in Kali, Gangavali, and Aghanashini (Table 2.1). It prefers soft intertidal muds bordering mangrove swamp forest (Pathansali, 1966) and salinity range of 13.69 – 34.40 ppt (Narasimham, 1988). Hence, A. granosa occurs only at the river-mouth where the salinity is usually high. This species was previously reported from Kali (Boominathan et al., 2012), Aghanashini (Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012), and Venkatapur (Rao and Rao, 1985) estuaries of Uttara Kannada District. Meretrix casta is distributed in Aghanashini and Gangavali (without any dams) estuaries from the river-mouth to six km interior. Compared to this, M. casta is distributed in Kali (with dam) only for three km range from the river-mouth (table 2.2) and its distribution area is now reduced due to the influx of fresh water releases from the hydroelectric projects at upstream. M. casta is a euryhaline species (adapted to a wide range of salinity) (Rao et al., 1989) with a greater degree of physiological adaptation in the salinity range of 25.00 to 56.00 ppt (Durve, 1963). M. casta is distributed only up to three kilometer distance from river-mouth as the salinity of Kali estuary is very low. Whereas in Sharavathi estuary M. casta is absent, probably because of extremely low salinity due to dam water releases. M. casta was reported earlier by various authors from Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, Sharavathi, and Venkatapur estuaries (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973; Harkantra, 1975a, 1975b; Rao and Rao, 1985; Rao et al., 1989; Bhat, 2003; Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012). Whereas the distribution of Meretrix meretrix in the undammed Aghanashini and Gangavali estuaries range from river-mouth to three kms inside, in Kali (with dams) M. meretrix has only a one km range from river-mouth (table 2.3). M. meretrix prefers high salinity (Rao et al., 1989) and hence its presence closer to the river mouth can be justified. In the Sharavathi estuary M. meretrix was present earlier (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973; Rao and Rao, 1985), but seems to have vanished today, due to the decline in salinity caused by release of fresh water from hydroelectric projects. M. meretrix is present to this day in all the other estuaries (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973; Rao and Rao, 1985; Rao et al., 1989; Bhat, 2003; Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012). Paphia malabarica occurs closer to the river mouths (Rao et al., 1989) with salinities of 20 to 30 ppt (Mohan and Velayudhan, 1998). It occurs to this day in the high salinity regions of Kali, Gangavali, and Aghanashini estuaries (table 2.4). However, in Sharavathi estuary P. malabarica was not reported earlier nor it occurs currently. The species occurs in all the other estuaries viz. Kali Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Venkatapur (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973; Harkantra, 1975a; Rao and Rao, 1985; Rao et al., 1989; Bhat, 2003; Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012). Table 2: Current distribution of bivalves in the Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavathi estuaries. P = Present.

Table 2.2: Current distribution of Meretrix casta.

Table 2.3: Current distribution of Meretrix meretrix

Table 2.4: Current distribution of Paphia malabarica.

Polymesoda erosa prefers salinity of 7 to 22 ppt (Modassir, 2000) and is present in all four estuaries (table 2.5). Even though, it is present in Kali, Gangavali, Aghanashini, and Sharavathi estuaries, the population is high in Sharavathi estuary than the other estuaries and also it is the only species of edible clam present to this day. P. erosa was earlier reported by Ingole et al., (2002) from Sharavathi estuary where it is still present. Boominathan et al., (2012), for the first time, reported its occurrence in Kali and Aghanashini estuaries. Villorita cyprinoides associated with medium salinity conditions is known to withstand freshwater conditions (Nair et al., 1984; Rao et al., 1989; Boominathan et al., 2012). It was reported from Kali (Rao et al., 1989; Boominathan et al., 2012), Aghanashini (Rao et al., 1989; Bhat, 2003; Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012), and Venkatapur (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973) estuaries. Extremely low salinity of Sharavathi estuary might have caused its present elimination from here where according to elderly fisher-folks the species was present earlier. In Kali estuary, which has more salt water ingress, despite the dams, it is found in 6-12 km range. It occurs in 5-16 km zone in Gangavali, and 9-23 km zone in Aghanashini respectively (table 2.6). Table 2.5: Current distribution of Polymesoda erosa

Table 2.6: Current distribution of Villorita cyprinoides

Oysters are present in all the estuaries (table 2.7), usually it occurs in moderate to high salinity regions in the estuary. They were also previously reported from Kali (Rao, 1974; Boominathan et al., 2012), Gangavali (Rao, 1974), Aghanashini (Rao, 1974; Boominathan et al., 2008, 2012), Sharavathi (Rao, 1974; Rao and Rao, 1985), and Venkatapur (Rao and Rao, 1985) estuaries. Table 2.7: Current distribution of oysters

Significant outcome of the current study are:

Citation:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||