|

Results & Discussion

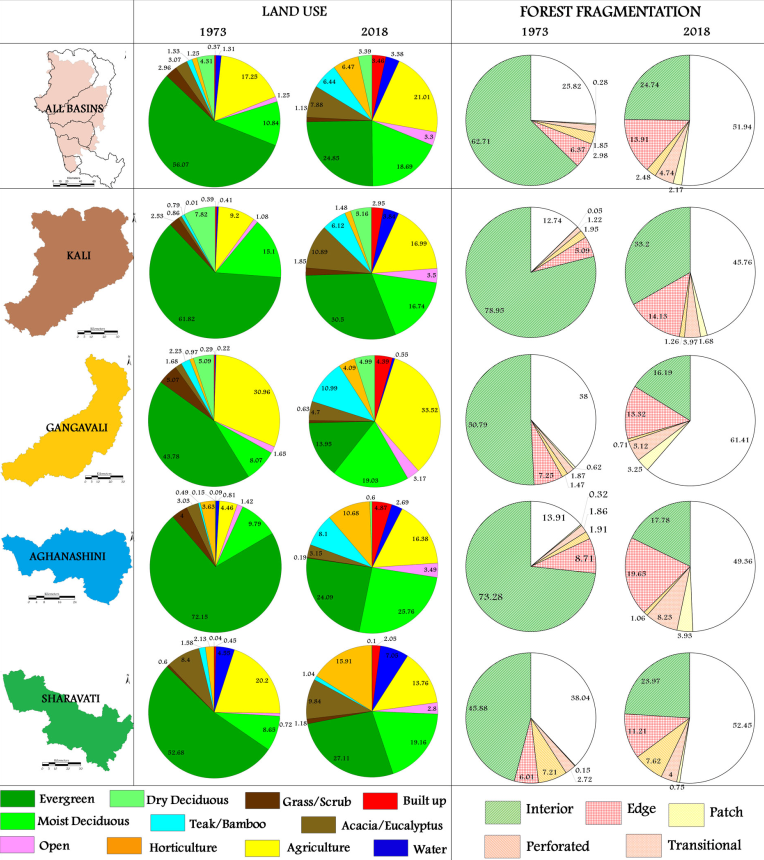

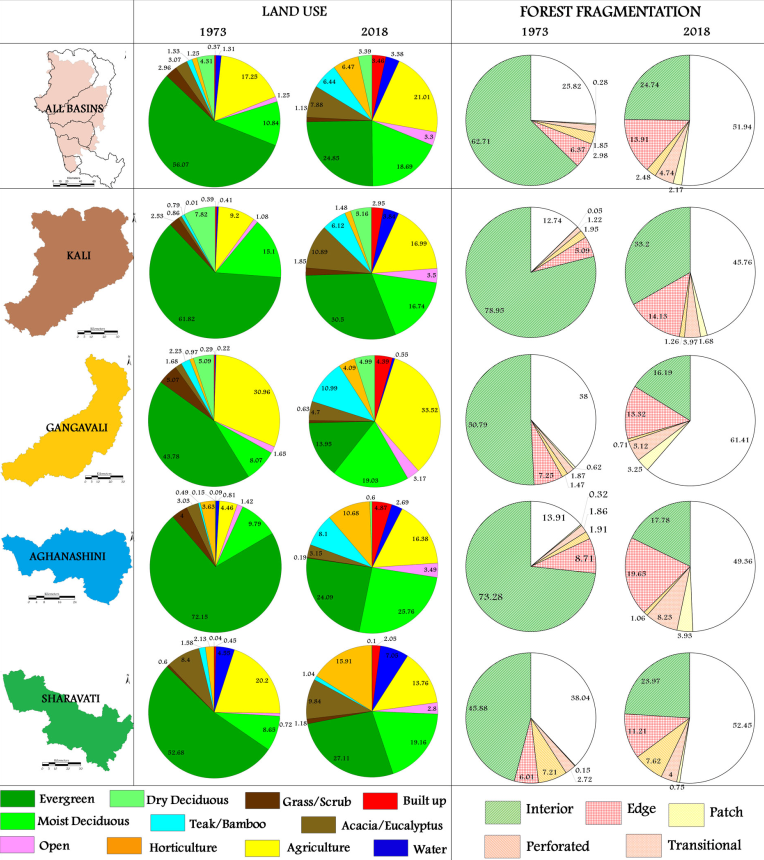

Status and transitions of forests: This is

evaluated through the assessment of land use dynamics and

fragmentation of forest landscapes using the temporal remote

sensing data of 1973 and 2018. Land use dynamics with the

fragmentation of forests across five major river catchments

of Uttara Kannada district in Central Western Ghats are

presented in Figure 3 and statistics are presented river

basin wise in Figure 4. Land use analyses using temporal

remote sensing data reveals that the overall forest cover in

the district has declined from 74.19% (1973) to 48.04%

(2018), with the loss of evergreen forests from 56.07% to

24.85%. The loss of forest cover is due to developmental

activities with the aggravated anthropogenic activities94

such as i) construction of dams along river Kali post 1975

without appropriate rehabilitation and catchment restoration

measures, ii) increase in monoculture plantations such as

teak, eucalyptus, acacia by the forest department as part of

social forestry scheme, iii) conversion of area under

forests to agriculture, horticulture or private

plantations82,95, iv) increase in built up area,

v) setting up of forest based industries, vi) nuclear power

plant at Kaiga in the midst of evergreen

forests75, etc.

Figure 4. Land use and forest fragmentation dynamics. Fragmentation process involves alteration in the structure

and composition of native forests through the division of

contiguous forest into smaller non-contiguous fragments with

a sharp increase in edges. This will have detrimental

effects such as disruption in bio-geo chemical cycling,

nutrient and water cycling, ecological processes, easier

access and further land use changes. About 64,355

Ha of forest land has been diverted for various non-forestry

activities (such as paper industries, hydro-electric and

nuclear power projects and commercial plantations) during

the last four decades by the government75. Due to

these, the terrestrial forest ecosystems in Uttara Kannada

district, Central Western Ghats have been experiencing

fragmentation of contiguous forests, evident from the

decline of interior or contiguous forests from 62.71% (in

1970) to 24.74% (2018) and consequent increase in patch,

transitional, edge and perforated forests. This has led to

the loss of connectivity natural/native vegetation and wild

animals straying into human habitations. Instances of

human-animal conflicts, has increased. There is also

extirpation of gene due to higher inbreeding, loss of

biodiversity, absence of native pollinators etc. Spurt in

urban growth is witnessed in and around major towns such as

Sirsi, Siddapura, Karwar, Hubli, Ankola, Kumta, Honavar,

Dandeli, etc. Encroachments of forest lands of the order of

7072 Ha75 and conversion to agriculture,

horticulture and private plantations throughout the district

(except the areas designated as protected areas) across all

agro-climatic zones (coast, ghats, plains, and transition

zones).

Figure 3: Dynamics in Land use, Forest cover and Forest

Fragmentation across the West flowing rivers of Central

Western Ghats

River basin wise land use analyses (Figure 4) reveals that

anthropogenic activities involving monoculture (both forest

plantation and horticulture) plantations and exploitation of

timber in the Aghanashini river basin have led to the

decline in the forest cover from 86.08% (1973) to 50.65%

(2018) followed by river basins of Kali (37.8%), Gangavali

(37.7%) and Sharavati (23.3%).

Evergreen forest cover in Aghanashini riverscape has declined

from 72.15% (1973) to 24.09% (2018), while moist deciduous

forest cover has increased from 9.79% to 25.76% during this

period. While there has been a sharp increase in

agricultural activity from 4.46% to 16.38% in the coastal

regions, on the Ghats and transition zones to the east,

horticulture practices (Arecanut gardens) have increased

from 3.63% to 10.68%, especially along the river valleys and

stream courses. Urban growth has picked up as indicated by

increase in built-up areas from 0.1% to 4.87% in the

proximity of the coast (Gokarna and Kumta) and along the

Ghats (Sirsi). There has been a reduction in the interior

forest cover from 73.28% to 17.78%, with increase in edge

forests (from 8.71% to 19.65%) and transitional forests

(from 1.86% to 8.23%).

Construction of series of dams in the Kali river basin at

Supa, Kodasalli, Kadra, etc.52 has resulted in

loss of forest cover (from 87.26% to 54.24%) and in

particular the evergreen forests (from 61.82% to 30.5%). Due

to the availability of water and lack of appropriate

regulatory mechanism, there have been forest encroachments

in the eastern part of the catchment (near Hubli and

Belgaum) leading to increase in agricultural and

horticulture activities (17.02% to 22.15%). Overall, the

forest cover in Kali river basin has reduced. Infrastructure

activities (Karwar, Hubli – Dharwad) have boosted the growth

of urban areas from 0.39% to 2.95%. All these pressures have

reduced the contiguous native intact forest from 78.95% to

33.2% in the Kali river basin.

Similar level of anthropogenic stress was witnessed in the

Sharavati river basin which has led to the decline in forest

cover (from 61.97% to 47.55%) with the loss of evergreen

forests (from 52.68% to 27.11%) and an increase in deciduous

forests by two fold. Human animal conflicts have increased

due to the disruption of animal movement paths with the

decline of the contiguous intact (interior) forests from

45.88% to 23.97% and loss of fodder, water, etc. with

decline of native vegetation. There has been an increase in

urban spaces (0.45% to 2.05%), and horticulture lands (2.13%

to 15.91%), etc. Also, the decline in agricultural practices

in Sharavati river basin was noticed with the large scale

conversion of paddy fields into cash crop fields like areca

gardens, etc.

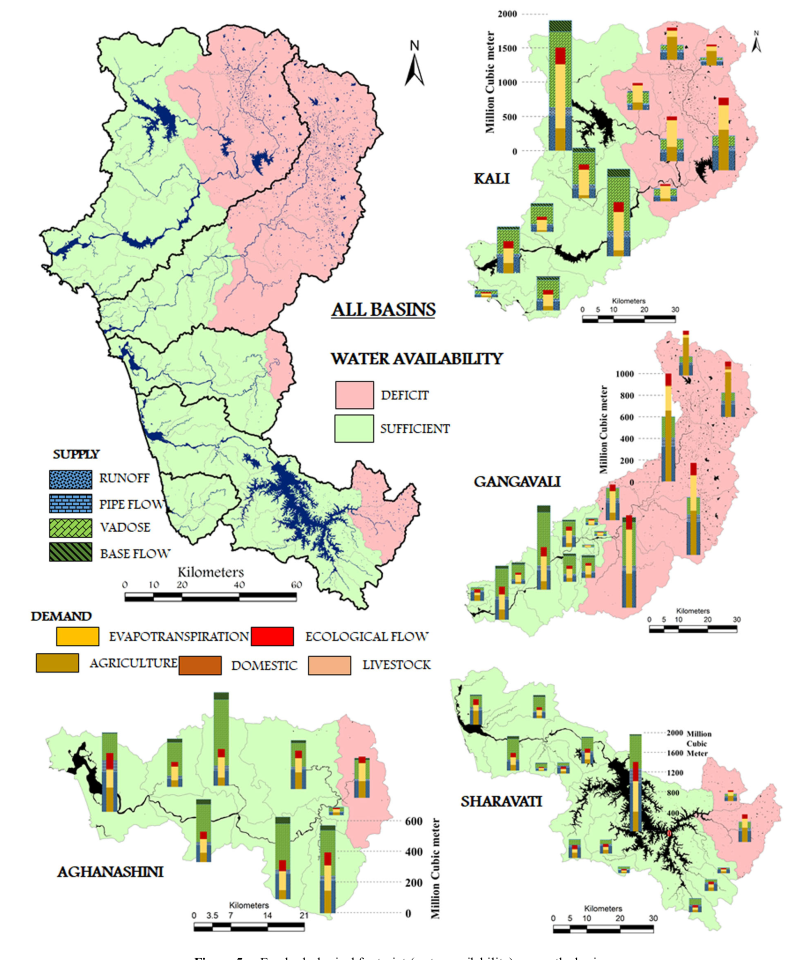

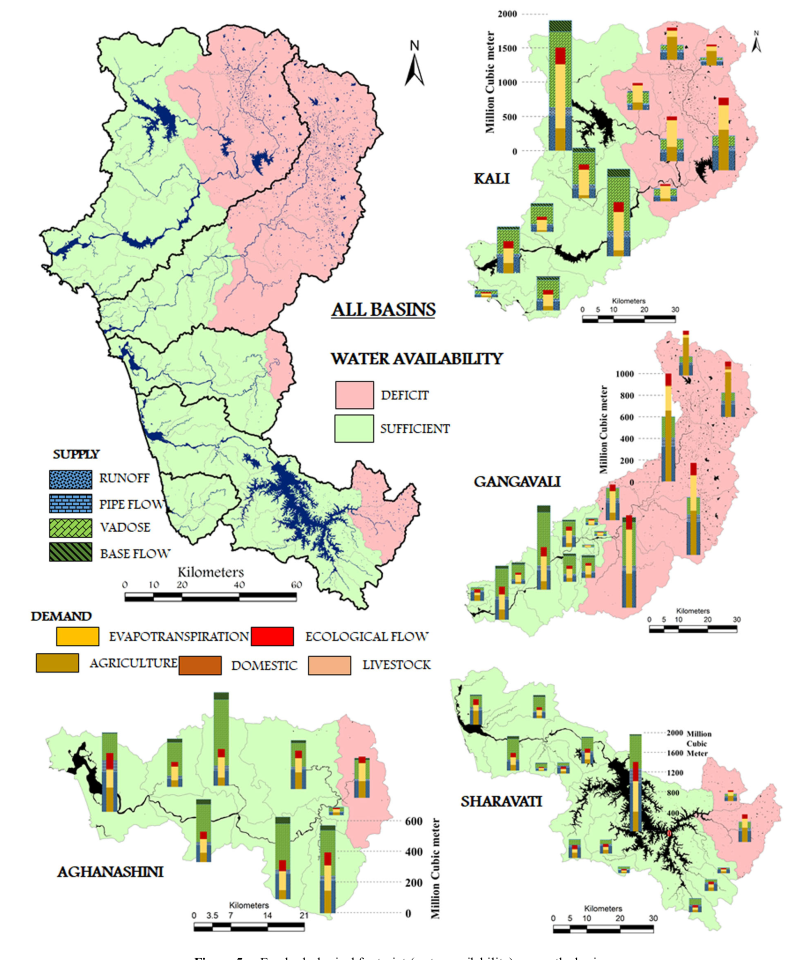

Figure 5: Eco-Hydrological Footprint (Water Availability)

across the basins

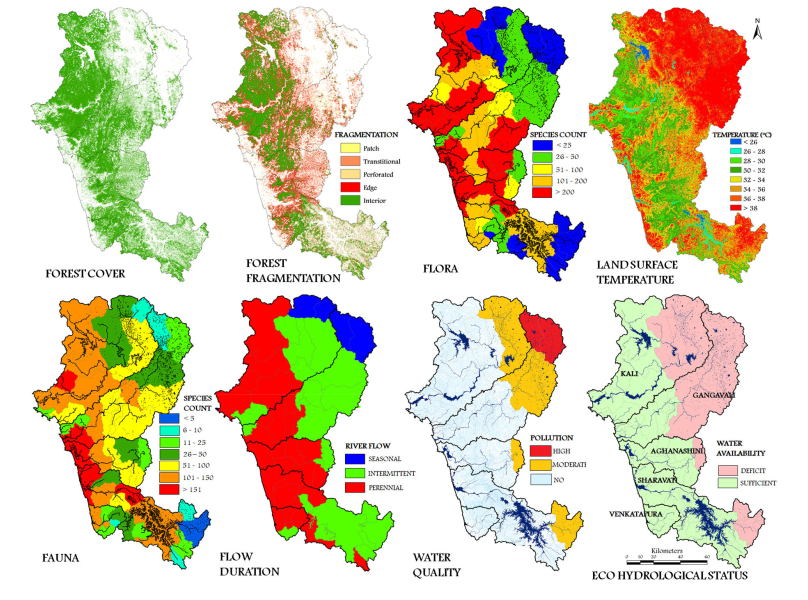

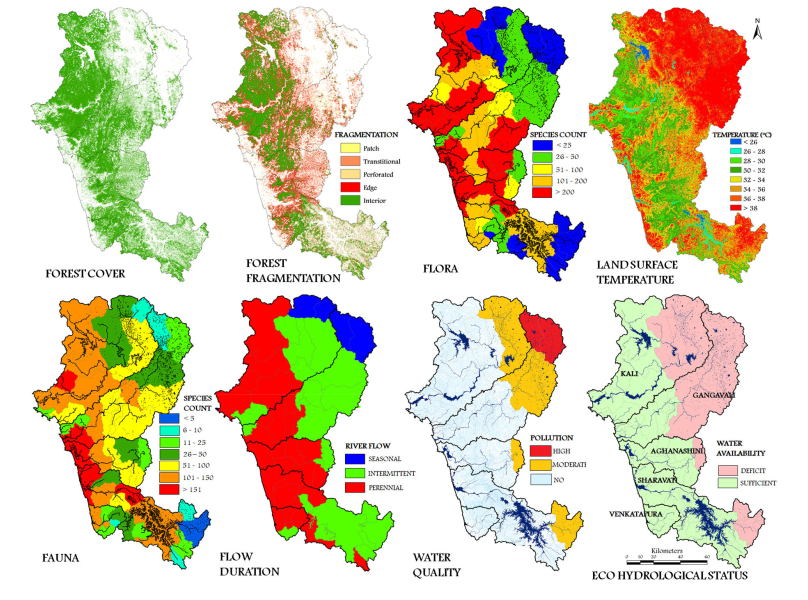

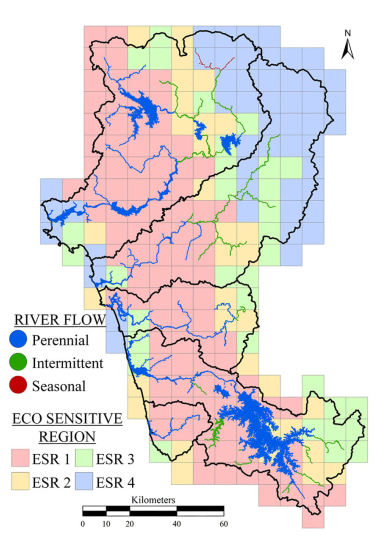

Figure 6.

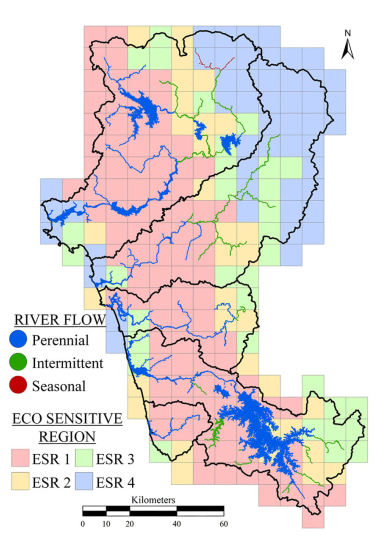

Eco-hydrology and forest linkages.  Figure 7: Ecologically Sensitive Regions in Uttara Kannada

District People’s livelihood and eco-hydrological status

of a catchment: A comparative assessment of

people’s livelihood has been made with soil water properties

and availability of water in the respective catchment. The

result shows that, catchments with > 60% vegetation with

native species has higher soil moisture and groundwater in

comparison to the catchment (of seasonal stream) during dry

spell of the year. The higher soil moisture due to the

availability of water during all seasons facilitates farming

of commercial crops with higher economic returns to the

farmers, unlike the farmers who face water crisis during the

lean season. The study emphasizes the need for conservation

endeavour on maintaining native vegetation in the catchment,

highlighting its potential to support people’s livelihood

with water conservation at local and regional levels. Both

plantation and agricultural crops have been considered for

the valuation in the select catchments of perennial and

seasonal streams. Plantation crops (viz. areca nut, coconut,

banana, beetle leaf and pepper) are the major income

generating products in the catchment of perennial streams. A

total amount of Rs. 3,11,701 ha-1

yr.-1 (year 2009-10) gross average income was

generated from the plantation crops against an average

expenditure of Rs. 37,043 ha-1 yr.-1,

(mainly for plantation maintenance), yielding a net profit

of Rs.2,74,658 ha-1 yr.-1. On the

contrary, for the catchment of seasonal streams, (where both

plantation and rice fields were considered for income

calculation) the average gross income generated was Rs.

1,50,679 ha-1 yr.-1 against

expenditure of Rs. 6474.10 ha-1 yr.-1

for plantation maintenance and field preparation.

Faunal diversity and total economic value: The

presence of contiguous or intact forests with the native

species maintain the natural flow conditions and water

quality. Alteration in the natural flow regime through

construction of reservoirs for impounding water and

releasing as per societal needs has led to an imbalance in

the ecosystem, loss of habitat, alteration in water quality

etc. Altogether 61 fish species from 47 genera and 38

families were recorded from the Kali estuary. Gangavali, has

55 species of fish from 46 genera and 39 families.

Aghanashini has highest diversity of fishes; 86 species

belonging to 66 genera and 47 families, while Sharavati has

lowest with 43 species from 25 genera and 24 families60,99.

This high diversity in Aghanashini estuary is obviously due

to preservation of the relative naturalness of the river,

unaffected by dams or other major developmental projects.

However, shell and sand mining that have intensified in

recent decades, have telling effect on estuarine fish

population and livelihood based on them60.

These four estuaries spreading across 7,549 ha area,

constitute a very important employment sector in the

district, accounting for about 2,092,000 fishing days/year,

benefiting altogether an estimated 3,086 families of

estuarine fishermen, generating 277 days of fishing work per

year and generating an income of Rs. 88,157/ha/year. This is

significant considering income is without any input from

humans except on fishing efforts through human energy alone,

as mechanized fishing is not practiced in the estuaries of

the district. The estuarine area required for fishing was

0.56 ha per head in Gangavali and Aghanashini (both are

without dams), 1.58 ha in Kali and a whopping 4.72 ha in

Sharavati (impacted by series of hydro-electric

projects).

Table 1 lists estuarine faunal diversity with the total

economic value, which highlights the importance of

maintaining natural flows to sustain the estuarine diversity

and also ecosystem goods and services. Natural flows are

regulated in the Kali and Sharavati rivers with reservoirs

built across them for producing electricity at Supa,

Kodasalli, Kadra (Kali) and Linganmakki (Sharavati).

Controlled flows alter the salinity and nutrient levels in

the estuaries, which results in the lowering of goods and

services as evident from the Total Economic Value (TEV) per

hectare. The TEV is 1.2 Million Rupees (Sharavati) and 2.5

Million Rupees (Kali) as compared to 5 Million Rupees per

hectare per year in the Aghanashini or 2.6 Million Rupees

per hectare per year in the Gangavali rivers. Gangavali and

Aghanasini rivers are devoid of reservoirs and the flow in

these rivers are natural. This ecology also has led to

higher diversity of bivalves which consists of about 13

species in Gangavali and 86 species in

Aghanashini65. The study reiterates the need for

maintaining the natural flow regime and prudent management

of watershed to i) sustain higher faunal diversity, ii) to

maintain the health of the water body and iii) to sustain

people’s livelihood with the higher revenues. The study

negates the current decision makers approach with an

assumption ‘Fresh water flowing into the Sea is a waste

of a precious natural resource’, and highlights the

importance of maintaining forests with native vegetation in

the catchment areas to sustain water quality and quantity of

the rivers during all the seasons. The unregulated flows in

rivers can maintain the health and biodiversity in the

downstream regions also including coastal waters, wetlands

(mangroves, seagrass beds, floodplains), and estuaries.

Table 1: Estuarine faunal diversity and total economic

value(TEV) 65,71,84,100

River Basin |

Dams |

Fishes

(Sp. Count) |

Gastropods / Bivalves (Sp. Count) |

TEV Rs. per hectare per year |

Kali |

6 Reservoirs |

61 |

7 |

2.5 Million |

Gangavali |

Presence of small check dams |

55 |

6 |

2.6 Million |

Aghanashini |

Presence of small check dams |

86 |

7 |

5.0 Million |

Sharavati |

3 Reservoirs |

43 |

2 |

1.3Million |

Citation :Ramachandra T. V., Vinay S., Bharath S., Subash Chandran M. D. and Bharath H. Aithal, 2020. Insights into riverscape dynamics with the hydrological, ecological and social dimensions for water sustenance, Current Science, Vol. 118(9): 1379-1393

|