|

Impact of Hydroelectric Projects on Bivalve Clams in the Sharavathi Estuary of Indian West Coast

|

|

M. Boominathanta,b, G. Ravikumarb, M. D. Subash Chandrana, T.V. Ramachandraa,*

aEnergy and Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore - 560012, India,

bA.V.V.M. Sri Pushpam College, Poondi - 613503, Tamil Nadu, India

*Corresponding author: cestvr@ces.iisc.ac.in

Materials and Method

Study area

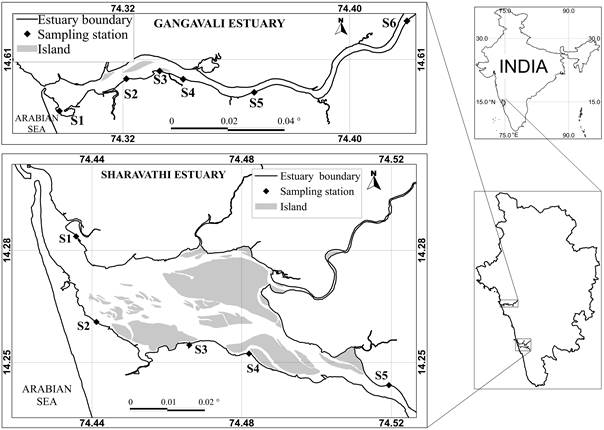

The survey was conducted on the Sharavathi and the Gangavali estuaries along the Arabian Sea coast of Uttara Kannada district in South-west India, in the Karnataka State during August 2011 to July 2012 (Fig. 1). The study area map was created in QGIS version 1.8.0 (Quantum GIS Development Team, 2012). Sharavathi originates in the Western Ghats of Tirthahalli Taluk of Shimoga district and has a total length of 128 km to its river mouth close to Honavar town. The estuarine portion was traditionally understood to having extended from the river mouth to Gerusoppa, about 27 km upstream, towards the foothills of the Western Ghats. The total area of the estuarine portion was stated to be 1600 ha (Kamath, 1985; Rao et al., 1989). Sharavathi has a power generation history dating back to commissioning in 1948 of a 120 MW power house in it (Jog Management Authority, 2014), now with 139.20 MW capacity. In 1964 a large dam was built at Linganmakki with a 55 MW power generation capacity. Using the waters Linganmakki dam Sharavathi Power Generating Station was commissioned with 10 units and installed capacity of 1035 MW. One more dam was commissioned at Gersoppa in 1999 with an additional power generation capacity of 240 MW (Karnataka Power Corporation Ltd., 2011).

The river Bedti or Gangavali originates in the Dharwad district, towards the eastern fringes of the Western Ghats, bordering the Deccan, and has a total westward course of 161 km to its river mouth close to Ankola town in Uttara Kannada. In the Gangavali river, which has no hydel project, the high tide from the sea travels upstream to a village Gundbale, about 15 km interior. The estuarine of the river is spread an area of about 640 ha (Kamath, 1985; Rao et al., 1989).

Fig. (1). Gangavali and Sharavathi estuaries in Uttara Kannada district. Gangavali. Abbreviations of station code as given in the table 1.

Salinity measurement

Surface water salinity was measured in both the estuaries, in the field itself, during high tide using EXTECH EC 400 salinity meter in December 2011, after the total stoppage of the rainy season. In Gangavali, unaffected by dams, salinity was measured in six stations covering a total distance of about 15 km upstream until the upstream limit of marine tides beyond which no estuarine bivalves were to be found. In Sharavathi estuary, with two hydroelectric projects upstream in the river, salinity was measured from five stations covering a total distance of 12 km upstream. The salinity status line graph was prepared by using statistical software R version 3.0.2 (R Development Core Team, 2013).

Bivalve data collection

Bivalve studies are normally conducted in the respective species specific habitats. Mudflats and sandy bottoms were known as preferred habitats for some common commercial estuarine clams of the Indian west coast such as Meretrix casta, M. meretrix, Paphia malabarica, Polymesoda erosa, Tegillarca granosa, and Villorita cyprinoides (Apte, 1998; Boominathan et al., 2008). As expectedly these clams also occurred in the Aghanashini estuary of Uttara Kannada (Boominathan et al., 2008), situated between the case study areas of Gangavali and Sharavathi estuaries. All out searches were made during low tides in the mudflat and sandy bottom of Gangavali and Sharavathi estuaries for these common clams of the Indian west coast. Professional clam collectors' help was also taken in collecting the clams from their expected habitats such as mudflats and sandy bottoms. As sand mining was happening in the upstream parts of the Sharavathi estuary mined sand also was searched for clams. In addition, 20 fisher-folks of Gangavali and 25 of Sharavathi estuaries were shown specimens of different clams of the region to ascertain their locations of occurrence in the respective estuaries, currently or in the past. The clam bivalve shells collected were identified using the diagnostic characters given in the relevant literature (Apte, 1998; Dey, 2006; Morton, 1984; Rao, 1989; Rao et al., 1989). The past studies on clam bivalves from the Gangavali and the Sharavathi estuaries (Alagarswami and Narasimham, 1973; Rao et al., 1989; Rao and Rao, 1985) were also referred to, for understanding any changes that might have taken place in their occurrence currently. The limitation of the current study, admittedly, is the paucity of earlier published studies on Sharavathi dealing with the species-wise ranges of clam distribution. The few earlier works available focused mainly on one or few commercial species than the entire range of commercial bivalves that would have occurred in the estuary.

Citation : M. Boominathan, G. Ravikumar, M. D. Subash Chandran and T. V. Ramachandra, 2014. Impact of Hydroelectric Projects on Bivalve Clams in the Sharavathi Estuary of Indian West Coast, The Open Ecology Journal,2014, 7, 52-58

|

|