Plant Diversity in Goa, Central Western Ghats

T V Ramachandra, Sudhansu Sekhar Sethi, Vishnu D Mukri

IISc-EIACP, Environmental Information System, CES TE15

Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012

E Mail: tvr@iisc.ac.in,

envis.ces@iisc.ac.in,

Tel: 91-080-22933099/23608661

Abstract

Characterisation and spatial mapping of vegetation would aid for making scientifically sound environmental decisions. Characterisation of plant species has been done through field surveys involving plant specimen collectionss, which were identified using taxonomic keys and validated in consulation with the subject experts. The collected data were analyzed to determine density, evergreeness and endemism as well as to identify areas of high conservation value. Goa's flora is diverse, with a total of 1041 species belonging to 494 genera and 151 families.

Keywords: Plant diversity, Flora, Western Ghats, Endemic plants, Biodiversity

Introduction

Plant diversity refers to the variety of plant species found in a particular or habitat. It describes plant varieties, their distribution, and the ecological role in the ecosystem. Understanding plant diversity is critical for conservation efforts and natural resource management [1]. Vegetation refers to an assemblage of plants growing together in a certain site, and it can be distinguished either by its component species or by the combination of structural and functional characteristics that form the appearance, or physiognomy, of vegetation. [2, 3]

India has the distinction of one of the 12 mega diversity countries [4] with about 126,000 species. India has 8% of the global biodiversity, even though it covers only 2.4% of the land area of the world [5]. The Eastern Himalayas and Western Ghats are also among the 36 global biodiversity hotspots [5]. The Western Ghats covers only 5% of the land area of India, but has 30% of India's species. It has about 5,000 flowering plant species of which 1,500 are endemic [6]. There are 58 endemic plant genera, of which 42 are monotypic. About 490 species of trees occur of which 308 (62.5%) species in 58 families are endemic. About 267 species of orchids occur belonging to 72 genera, of which 130 species are endemic.

Goa, a small state on India's western coast, is endowed with a diverse forest flora that has evolved as a result of its unique tropical temperature, geology, geography, and human land usage. The flora of Goa is notable for its high species variety, having an estimated 2,000 to 3,000 plant species [7, 8]. Goa's floral diversity is critical, and these plants have been used by local communities for a variety of purposes, including food, medicine, and ornamental use.

Goa's flora is characterised by a varied range of plant species that have adapted to the region's tropical temperature, geology, geography, and human land usage. Goa's flora includes several plant species that are endemic to the Western Ghats, such as the Gnetum ula and Memecylonramakrishnanii [7]. Endemism is a result of the unique geological and climatic conditions of the Western Ghats, which have led to the evolution of distinct plant lineages over time [9]. Several plant species have medicinal value and are used being used in traditional medicine. For example, the Acorus calamus is used to treat digestive disorders, while the Cassia fistula is used as a laxative [10]. The medicinal properties of many plant species in Goa have been documented in traditional knowledge systems, as well as in scientific studies [11]. Many plant species in Goa have economic value and are used for various purposes, such as timber, fuel, fodder, and food. For example, the Mangifera indica is a popular fruit tree, while the Acacia auriculiformis is grown for its wood [7]. The economic importance of these plant species has led to their cultivation and management by local communities.

Goa, a state on India's western coast, is famed for its lush woods, which plays critical role in maintaining the region's natural balance. The history of the state's forests may be traced back to the pre-colonial period, when forests covered a large portion of the territory. Agricultural practices also marked significant changes in the Goa Forest patches. “Slash and Burn Cultivation” was extensive during 12th to 14th century where the local tribes of Goa ‘Kumeri’ used this method for their agricultural practices. This is evident from the presence of fire tolerant trees along with invasive species [12].

The Kadamba dynasty, which ruled Goa between the 10th and 14th centuries, is credited with introducing advanced agricultural practices such as terrace farming and the kumeri system of paddy cultivation. The Portuguese, who ruled Goa from the 16th to 20th centuries, also left their footprint on the agricultural practices, introducing cash crops like tobacco, sugarcane, and spices, which became important exports for the region [13]. Portuguese in the early 16th century, promoted forests for economic purposes, such as timber extraction and mining. The establishment of mines for extracting iron and manganese ores resulted in heavy logging and destruction of large tracts of forests, and loss of valuable biodiversity.

The Myristica swamp forest, also known as the ‘Relic Forest’ are the ancient forest patches which have not undergone any disturbance or alternation in its species composition due to anthropogenic activities done by humans. They are ecological indicator of a good forest patch referring a highly productive ecosystem that also supports diverse biodiversity including threatened species and provides numerous benefits to people [14]. It strongly influences the organization, diversity, and dynamics of communities associated with aquatic ecosystems [15]. These Swampy relics forest harbours many critically endangered to endemic species within its habitat which includes recently identified species like Semecarpuskathalekanensis, and Syzygiumtravancoricum [17]. Sacred Grooves or ‘Devrai’ (in Konkani language) are patch of forests conserved as sacred dedicated to deities [16].

Dudani et al. (2014) reported threatened tree fern 'Cyathea nilgirensis' in sacred groves. The ecological significance is evident from the occurrence of critically endangered primitive flowering species, Myristica magnifica (Endangered), Dipterocarpus indicus (Endangered), Gymnacrantheracanarica (Vulnerable), Syzygiumtravancoricum (Critically Endangered), and Semecarpuskathalekanensis (Critically Endangered) [18].

Jagtap et al. (2005) demonstrated the characterization of Porteresiacoarctata along the Goa coast by studying and analysing P. coarctata characteristic features that varied with changing time periods. The biomass and growth of P. coarctata were negatively correlated with salinity and positively correlated with nitrite and nitrate and the leaf and tiller length of P. caorctata was greatest during the monsoon season and least during the pre- and post-monsoon seasons [19].

Dudani et al. (2013) conducted research on fern diversity in the Yana Forestand reported 21 fern species, with Pteridaceae dominating with 5 species, as well as endemic fern species such as Bolbitissemicordata and Bolbitissubcrenatoides [20].

Desai et al. (2008) carried out studies of phytoplankton diversity along the Sharavati river basin and reported the presence of 216 phytoplankton species with uneven distribution having Bacillariophyceae (diatoms) predominating stream water samples and Desmidials (desmids) predominating reservoir ones which ultimately suggest the higher eutrophic nature of streams than reservoir waters. Other families such as Cyanophyceae, Chrysophyceae, Euglenophyceae and Chlorococcales are also found in the collected samples [21].

Rao et al. through multiple belt transects along evergreen to semi-evergreen forests t in the MPCA at Shirgunji and documented 122 species was discovered including 61 medicinal trees, 21 shrubs, 20 climbers, and 20 herbs, with endemic species such as Garcinia cambogia, Garcinia indica, Perseamacrantha, and Cinnamomum malabathrum [22].

Chanda and Ramachandra (2019) studied vegetation of Sacred Groves in India in six different geographical regions documented 1740 plant species, with angiosperms having 1582 species and dominant plant forms including trees (35.33%), herbs (34.88%), shrubs (19.55%), climbers (8.21%), orchids (1.01%), and epiphytes (0.63%). The northern zone had the highest species diversity, while the western zone had the lowest. During research, the family Leguminosae was discovered to be dominant, followed by the families Laminaceae and Asteraceae.They also highlighted the threats responsible for the vulnerability of the sacred grove species which include anthropogenic pressure, agriculture conversion of forest into land and road construction, fencing, silviculture invasion and encroachment [23].

Rao et al. (2008) enumerated the floral diversity of wetlands of Uttara Kannada by collecting the samples from 29 different locations having various zones. Species identification was done by referring regional floras. Results reveal the presence of 167 floral species with 17 among them to be endemic ones and 26 species having medicinal values. Cyperaceae was the dominant with 50 species followed by Scrophulariaceae, Poaceae, Lythraceae etc. Among 167 species, 97 of them were annuals, 42 were perennials and 25 can be either of above depending upon wetland [24].

Priyanka and Minakshi (2019) conducted field studies to assess the state of plant diversity in castle rock. Species were sampled at various seasons and identified using flora books. The findings revealed the presence of 25 families and 39 species of flora, with moist-deciduous tree species such as Xylia xylocarpa, Terminalia paniculata, and Terminalia tomentosa as dominating forest vegetation. It also suggested that there will be a loss of flora species in this area hence requires proper attention for long-term development [25].

Manas et al. (2021) used the belt-transect method to investigate the structure and regeneration potential of the Similipal Biosphere Reserve over a year from various forest types such as dry deciduous forests (DDF), moist deciduous forests (MDF), and semi evergreen forests (SEF). Online floras like IPNI, GRIN was referred for Species identification and phytosociological parameters like density, regeneration potential, relative frequency and important value index was used for data analysis. Results showed a total of 84 tree species (35 families) with DDF having species richness of 54 (28 families) with tree density of 957 followed by MDF (848 in/h) and SEF (837 in/h). The size-class distribution of trees and juveniles showed a reverse j-shaped curve, indicating that the forest’s regeneration potential was quite good. Species like S. robusta, T. tomentosa, and X. xylocarpa were dominant in overall forest types. Despite DDF’s species richness, forest diversity was found to be low in comparison to the other two forest types, due to biotic interventions such as grazing and logging, which necessitates proper conservation and management [26].

D'Souza and Rodrigues (2006) documented the ethnomedicinal uses of 157 plant species in the forests of Goa. The authors noted that many of these plant species are used by traditional healers to treat various ailments [27].

Suthari et al. (2021) used the belt-transect method to investigate the ecological status of forests in the Eastern Ghats as well as the role of tropics in forest management and conservation. Over the course of four years, plant specimens were collected and identified using regional floras in six regions of Vishakhapatnam. Phytosociological parameters such as density, regeneration potential, relative frequency and important value index were computed and the results reveal of a total of 151 tree species from 46 families with Rajupet (dry deciduous) having a species richness of 79 from 36 families and a tree density of 453 in/h followed by Sileru (moist deciduous) having a species richness of 75 from 32 families and a tree density of 718 in/h. The size-class distribution of trees and juveniles exhibited a reverse j-shaped curve indicating that the forest's regeneration potential was excellent. In general, species such as Diospyros paniculata, Diospyros sylvatica, Gmelina arborea, Grewia tiliifolia, Lanneacoromandelica, Syzygiumcumini, and Wrightia tinctoria were dominant. Despite DDF's species richness, forest diversity was found to be low owing to biotic interventions such as logging, illegal hunting, timber collection, non-timber forest products, and other development challenges such as mining and invasive species entry into reserved forest areas. It eventually resulted in biodiversity depletion, species extinction, and biodiversity reduction [28].

Chanda and Ramachandra et al. (2019) studied the rare, endemic, and threatened medicinal plants of the Western Ghats. The presence of 108 RET species from 81 genera and 53 families, including two gymnosperms and orchids was discovered. The dominant family Asclepiadaceae, had 16 species followed by Fabaceae (15 species) and Apocynaceae (12 species). Ceropegiamannarana, Celastruspaniculatus, Gloriosa superba, Santalum album, and Terminalia arjuna were found to be major dominant RET medicinal plants in the following study. They also emphasised the urgent need for conservation of these RET species, which were constantly threatened by over-exploitation and anthropogenic activities [29].

Satheeshkumar et al. (2011) identified 1,319 species of flowering plants in Goa, belonging to 138 families. The presence of several endemic and rare species, including threatened and critically endangered were documented [30].

Sangle et al. (2021) highlighted the effective monitoring and conservation strategies for the sustainable use of endangered plants by carrying out extensive surveys through multiples field visits by collection of species and taxonomic identification through referring different research works and journals. The presence of 30 plant species belonging to 14 families and 19 generas was concluded, among which 22 species were herbs, 04 were twiners, 02 were shrubs, 1 climber and 1 was epiphyte. Observed species including Ceropegiamsahyadrica, Chlorophytum bharuchii,Sonerilascapigera, Begonia phrixophyllaandBigoniatrichocarpawerefound supporting ecologically specialized microhabitat to some vascular plant species. They also highlighted the threats which include illegal trade, over-exploitation, habitat loss, habitat fragmentation, over grazing and suggested suitable strategies for conservation the domestic cultivation of endangered plants. [31]

Chanda and Ramachandra et al. (2019) highlighted the distribution and usage of medicinal plants found in the sacred groves of South-western West Bengal. Information on the ethno-medicinal plants of sacred groves was gathered from seven papers covering sacred groves in West Bengal, then data was analysed to generate baseline information on disease type, curing plants, and usage patterns. The study reports of the presence of 257 medicinal plant species from 213 genera and 71 families. Leguminosae was the most numerous families, with 33 species, followed by Apocynaceae (21 species) and Malvaceae (15 species). Herbs dominated the forest area, accounting for 37.35% of total plant forms, followed by trees at 26.84% and climbers at 17.89%. Leaves had the highest usage pattern (25.48%), followed by roots (18.10%) and stem bark (11.14%). Species such as Ocimumtenuiflorum, Mimusopselengii, Azadirachta indica, Tamarindus indica and Madhuca indica were used to treat a variety of diseases. They also emphasised the importance of proper management and conservation of these medicinal species, which were threatened by a variety of biotic interventions [32].

Sawant and Rodrigues (2015) conducted a study of South-goa medicinal plant species by collecting samples during field visits, listing the methods for preparation and administration of medicines from local practitioners, and taxonomic identification using various bibliographies. The presence of 50 medicinal plant species from 20 families and 46 genera was observed treating 18 human ailments. The study revealed decoction was the most common method of preparation of medicine, followed by paste and poultice were using of combination of plant species was seen to be most effective. The dominant families are Combretaceae, Cucurbitaceae, and Apocynaceae, each with 7 species, followed by Anacardiaceae and Asteraceae, each with four species. The enlisted plants were found effective against human ailments like skin diseases, diabetes, jaundice, menstrual cycle, and hypertension [33].

Chanda and Ramachandra (2019) carried out studies to determine the relationship between medicinal plant usage, phylogenetic, morphological, and phenological characteristics from eastern India. It was discovered that the Asterid I clade contains 320 medicinal species from 4 orders and 12 families. These species have a common ancestor, as well as common secondary metabolites and medicinal bio-activity resembling metabolite features. With 7 families, Lamiales was found to be the dominant genus, followed by Gentianles, which had 3 families. Their secondary metabolites included alkanoids and flavonoids, and were effective against fever, skin disease, and diarrhoea [34].

Divakara and Srinivasa (2015) conducted a comprehensive survey to determine floral composition and diversity by laying random multiple plot-based quadrats for biodiversity sampling in various forest types and then analysing the data using the Shannon-Wiener diversity Index. The findings revealed that species composition varies across forest types depending on climate, topography, soil, and surrounding disturbances. It also revealed that species such as Terminalia paniculata, Xylia xylocarpa, Careya arborea, and Grewia tillifolia had the highest IVI over most Goan forest types, indicating that deciduous tree species dominate the Goan forest [35].

Gurusamy et al. (2022) conducted floristic studies in foothills of Pilavakkal dam to highlight the diversity and the emergent need of conservation of the floral species of Western Ghats. Results revealed the presence of 127 species belonging to 42 families and 100 genera. They also highlighted the lack in acknowledgment and continuous misuse of forest species by people had made a severe impact of the species diversity of the forest. Hence, an emergence step towards the conservation of the area should be taken [36].

Objective: Objectives of this study are

- Investigating plant diversity along with their distribution in Goa forest.

- Comparative ecological assessment of plant diversity in degraded and untouched forest patch as well as in Myristica swamps.

Materials and Method

Study Area

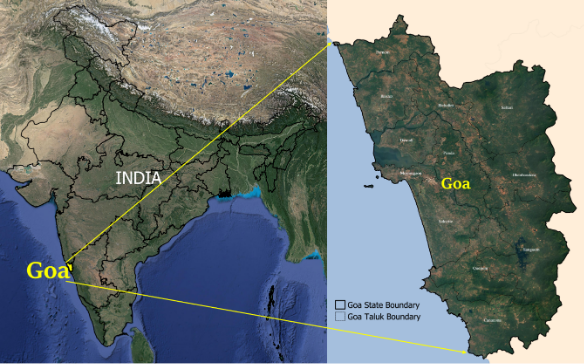

Goa is the smallest state in India and was formed in 1987. It is located on the western coast of the Indian Peninsula at latitudes 15˚ 48’ N and 14˚ 53’ 54" N and longitude 74˚ 20’ 13"and 73˚ 40’ 33" E. This state has a total area of 3702 km2 and a 104 km2 coastline [37].

Panaji is the capital of Goa, and the largest city in Goa is Vasco da Gama. The state comprises two districts: North Goa, covering 1736 km2, and South Goa, covering 1966 km2 and 12 taluks in total, such as Bardez, Bicholim, Pernam, Sattari, Tiswadi, Ponda (North Goa) and Canacona, Mormugao, Salcette, Sanguem, Quepem, and Dharbandora (South Goa) (Fig.1).

Figure 1: Goa State, India

Climate: The mean annual temperature is 27.8˚ C, while the mean minimum and maximum remain between 26.4˚ C to and 30.2˚ C, and the average monsoon rainfall is about 3910 mm. [38] Winter (December to February), summer or pre-monsoon (March to May), monsoon (June to September), and post-monsoon (October to November) are the four main seasons in the state [39]. The humidity level varies from 70% to 90%, which makes the climate warm and humid.

Geography: Geographically, Goa is divided into three regions: low-lying river basins with western coastal plains, midland regions with plateaus, and the hilly region of the Western Ghats in the west [40], where the majority of the land is occupied by pre-cambian rocks (quartz-sericite), and lateritic soil derived from pink phyllites is the dominant soil type [41].

Flora: Goa is rich in biodiversity since it is surrounded by the Western Ghats, which are considered biodiversity hotspots; forest areas containing both protected and unprotected sections. Cashew, Acacia, Teak, Rubber, Coconut, Areca-nut, and other plants can be found in Goa, where estuaries such as Terekhol, Chapora, Mandovi, Zuari, Sal, Talpona, and Galgibag support mangroves. In Goa's estuaries, there are 16 real mangrove species (including prominent species like Avicennia, Sonneratia, and Rhizophora) divided into 11 genera and seven families [42].

Forests: Goa's total forest area is 1424 sq. km., of which the government owns 1224.46 km2 including reserve forest covering 253.32 sq. km. classified under section 20 IFA; proposed reserve forest area up to 709.90 sq. km. under S/ 4 of IFA and unclassed forests spreads up to 261.24 sq. km. and the remaining 200 km2 is private forest. and the water covered area is 25,775 ha. Forest includes protected areas such as one national park, i.e., Mollem national park (107 km2), and six wildlife sanctuaries, i.e., Bondla wild life sanctuary (8km2), Bhagwan Mahavir wildlife sanctuary (133km2), Cotigao wildlife sanctuary (86km2), Salim Ali bird sanctuary (1.78 km2), Mhadei wildlife sanctuary (208km2), Netravali wildlife sanctuary (211km2) [42]. According to Champion and Seth classification (1968) of Forest types in India, the forests of Goa is divided into seven main categories which includes West Coast Tropical Evergreen Forests, West Coast Semi Evergreen Forests, Southern Moist Mixed Deciduous Forests, West Coast Tropical Evergreen Forests, West Coast Semi Evergreen Forests, Mangrove Forests, and Laterite Thorn Forests [43].

According to Mascarenhas, 2015, the goa forest is predominated by the fire tolerant species due to the Shifting cultivation done by the Kumeris and the floral species follows random spatial pattern of species distribution. Hence, the Point-centred quadrat method was found most suitable for the ecological assessment of floral diversity in Goa. Point centred Quarter method was first developed by Cottam and Cutis in 1950’s as a plotless technique to estimate density [44]. This method includes selection of a set of points along the transect area, division of area around point into quadrats of 90o each, measurement of distance (d) closest to the point followed by identification of species in each quadrat. Then the total average distance for all points in the transect is calculated (Xd).

2.1 Floral diversity in Goa Forest: -

The phytosociological character along with the distribution of total floral community including trees, shrubs and lianas in forest of Goa were thoroughly studied, revised and then enumerated into table specifying the present family classification (acc. to APG III classification) with their morphological characteristic features using online floras (India Biodiversity Portal, Flowers of India), research articles and books (Biodiversity documentation for Kerala pt.6 Flowering plants).

Results

Floral Diversity in Goa Forest: -

The following study is purely based upon the enumeration of flora diversity found in Goa’s Forest habitat by referring multiple sources such as Published books, journals & research articles and online flora.

A total number of 1041 plant species were enumerated during the floral studies belonging to 494 genus and 151 families. Fabaceae was found dominant family leading with 124 species followed by Poaceaewith 60 species, Malvaceaewith 51 species. Furthermore, about 390 tress species were found in floral diversity along with 595 species of shrubs and herbs and 56 species of lianas.

Dicotyledons dominated the floral composition in forest of Goa leading with 823 species belonging to 117 families. Monocots had 190 species belonging to 23 families, Pteridophytes with 27 species (10 families) and Gymnosperms with 01 species belonging to single family.

Enumeration of Floral species in Goa Forest are listed in Table 1.

Conclusion

Forest flora conservation is critical not just for preserving biodiversity, but also for maintaining ecological services that benefit human populations. Forest ecosystems in Goa are under threat from a variety of factors, including habitat destruction, fragmentation, degradation, and invasion by exotic species. Human activities like as mining, tourism, and urbanisation have resulted in forest loss and degradation, resulting in diminishing the amount of land accessible for plant growth and survival. Furthermore, invasive species, whether intentionally or mistakenly introduced, have entered natural habitats and are vying for resources with native species. The cultural and biological importance of Goa's forest flora, necessitate immediate interventions for conservation and prudent management. Moreover, the Family-wise mapping of distribution of floral species in Goa provided details of the structural compostition of the area.

Hence, the Goa Forest Department should develop suitable conservation methods for proper attention of these vulnerable floral species in its environmentally sensitive relics regions for long-term viability.

Plants of Goa

Table 1. Plants of Goa, Central Western Ghats

|

RANUNCULACEAE |

||

|

Family key (APG III System) |

Herbs or tendril climbing shrubs, flowers bisexual |

|

|

[55] Family description |

Dicotyledons. Leaves are opposite each other. Cymose flowers are regular. Petaloid perianth with 4-5 valvate or somewhat induplicate petals. Petals can be 0 or numerous. Stamens are numerous, hypogynous, and have free, filiform filaments; anthers are terminal, bilocular, and have adnate cells. Carpels many, free, I-celled, simple style; stigma on the inner side of the style at the top; ovules solitary, anatrope, pendulous; raphe dorsal. Fruit a head of plumose, I-seeded achenes. |

|

|

Generic key |

1. Clematis- Terminal leaflet in compound leaves not transformed into a tendril. Petals absent. |

|

|

[55] Genus description |

Leaves are opposite, frequently complex, with twinning petioles and no stipules. Flowers are beautiful and come in solitary, axillary, or terminal panicled cymes. Petaloid, 4-8 sepals, generally valvate. There are a lot of stamens. There are several carpels, each with one pendulous ovule. Achnes is either beaked or topped with a long feathery style. |

|

|

[52] Botanical name:Clematis hedysarifolia [53] Description: Woody evergreen climber; leaves simple or pinnate, often trifoliate, glabrous, shining; leaflets ovate, acuminate, cordate or rounded at base; venation prominent. Flowers axial or terminal, yellow green, cymose, leafy, bracteates panicles. Achenes orange or reddish, glandular hairy with rough, thickened margins. [53] Flowering & Fruiting: September to April Distribution: Goa:Sanguem |

|

|

|

Generic key |

2. Naravelia- Terminal leaflet transformed into a tendril. Petals many, linear, clavate. |

|

|

[55] Genus description |

The leaves are trifoliate. Flowers appear in axillary or terminal panicles that spread. 4-5 sepals. Petals are many, linear, and clavate, and are longer than sepals. Carpels are numerous on a small globose, hairy torus; the ovule is pendulous. Achenes are stalked and linear, with long feathery tails. |

|

|

[52] Botanical name:Clematis zeylanica(Naraveliazeylanica*) [53] Description: Leaflets are coriaceous, oval, and rounded at the base, with two opposing leaflets and a terminal stout. Flowers are small and emerge from axils or branch tips. Sepals are 4-5 oval, ribbed, and caduceus in shape. Petals are 6-12 straight and spathulate, and are longer than the sepals. Achenes that are crimson and covered in long, white hairs that are spirally curled and progressively narrow into long, feathery styles with thickened tips. [53] Flowering & Fruiting: October to April Distribution: Goa:Canacona; Geographical [53]: Nepal, Indonesia, Malaysia and Sri Lanka. [54] Medicinal Uses: Crushed roots are inhaled to treat colds and fevers, while fresh stems are chewed to treat toothaches and can also be used to alleviate chest pain and bone fractures. |

|

|

References

- Cardinale, B. J., Duffy, J. E., Gonzalez, A., Hooper, D. U., Perrings, C., Venail, P., & Naeem, S. (2012). Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486(7401), 59-67.

- Goldsmith, F. B., Morrison, R. G., & Cushing, C. E. (1986). Definitions of vegetation: a synthesis. Journal of Vegetation Science, 531-540.

- Heady, H. F. (1958). Vegetation and environmental patterns in the Santa Ana Mountains. Ecological Monographs, 28(1), 1-31.

- Myers, N. (Ed.). (1992). Tropical forests and climate (pp. 1-3). Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Khoshoo, T. N. (1995). Census of India's biodiversity: Tasks ahead. Current Science, 69(1), 14-17.

- Nair, S. C. (1991). The southern Western Ghats: a biodiversity conservation plan (No. 4). Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage.

- Shimpale, B. M., Kamat, N. M., & Gaikwad, S. P. (2012). The Flora of Goa State, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 4(6), 2615-2627.

- Gadgil, M. & Guha, R. (1992). This Fissured Land: An Ecological History of India. Oxford University Press.

- Mittermeier, R. A., Gil, P. R., Hoffmann, M., Pilgrim, J., Brooks, T., Mittermeier, C. G., & Lamoreux, J. (2004). Hotspots Revisited: Earth's Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CEMEX.

- Kamat, N. (2008). Goa's Plant Wealth. Botanical Survey of India.

- Pandey, S. K., Upadhyay, S., & Tripathi, S. C. (2011). Traditional Uses of Medicinal Plants among the Rural Communities of Chhattisgarh Plain, India. Ethnobotanical Leaflets, 15, 81-100.

- Mascarenhas, A. (2015). Goa's forests: A journey through time. International Journal of Scientific Research and Reviews, 4(3), 89-94

- Lobo, D. D. (2009). The agricultural history of Goa. In L. Rodrigues & U. S. R. Prusty (Eds.), The Environment and History: The Tensions of Nigeria’s Development (pp. 86-102). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Agbagwa, I. O., and Chimezia, Ekeke. (2011). Structure and Phytodiversity of fresh water swamp forest in oil rich Bonny, Rivers State, Nigeria. Research journal of Forestry. 5(2): 16-77.

- Gregory, S. V., Swanson, F. J., McKee, W. A. (1991). An ecosystem perspective of riparian zones. BioScience, 40: 540–551.

- Chandran, M.D.S. & D.K. Mesta (2001). On the conservation of the Myristia swamps of the Western Ghats, pp. 1–19. In: Shankar, R.U., K.N. Ganeshaiah & K.S. Bawa (Eds.). Forest Geneti Resources: Status, Threats, and Conservation Strategies. Oxford & IBH, New Delhi. Prabhugaonkar, A., Mesta, D. K., & Janarthanam, M. K. (2014). First report of three redlisted tree species from swampy relics of Goa State, India.

- Sumesh N. Dudani, S.N., M.K. Mahesh, M.D.S. Chandran & T.V. Ramachandra (2014). Cyathea nilgirensis Holttum (Cyatheaceae: Pteridophyta): a threatened tree fern from central Western Ghats, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 6(1): 5413–5416.

- Tanaji G. Jagtap, Siddharth Bhosale, Singh Charulata. Aquatic Botany 84(2006), 37-44.

- Sumesh N. Dudani, M. K. Mahesh, M. D. Chandran, T. V. Ramachandra. Indian Fern J. 30: 61-68 (2013).

- Desai S R, Subash Chandran M D, Ramachandra T V. The Icfai University Journal of Soil and Water Sciences, Vol I, No 1, 2008.

- G. R. Rao, M. D. Subash Chandran, T. V. Ramachandra. Diversity and Regeneration status of medicinal plants in Medicinal Plants Conservation Area (MPCA) at Shirgunji of Uttara Kannada District, Central Western Ghats. My Forest-March-June 2015, Vol. 51, pp 85-99.

- Sayantani Chanda, T. V Ramachandra. Vegetation in the Sacred Groves across India: A Review. Research & Reviews: Journal of Ecology, 2019; 8(1) 29-38p.

- Rao G. R., Divaker K. Mesta, Subash Chandran M. D. and T. V. Ramachandra, 2008. Wetland flora of Uttara Kannada in Environment Education for Ecosystem Conservation, Ramachandra (ed.), Capital publishingcompany, New Delhi, pp 152-159

- Priyanka Patil and Minakshi Mahajan. Plant Diversity at Castle Rock, Goa. Int. Journal of Universal Science and Technology ISSN: 2454-7263, Volume: 05 No: 03 Published: Jan., 2019.

- Manas R. Mohanta, Saloman Sahoo, Sudam C. Sahoo. Variation in structural diversity and regeneration potential of tree species in different tropical forest types of Similipal Biosphere Reserve, Eastern India. Acta Ecologica Sinica 41 (2021) 597–610.

- D'Souza, M. J., & Rodrigues, E. (2006). Ethnomedicinal plants used for digestive disorders by the traditional healers of Goa, India. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 103(3), 547-554.

- Mardana Tarakeswara Naidu, Sateesh Suthari, P. Balarama Swamy Yadav. Measuring ecological status and tree species diversity in Eastern Ghats, India. Acta Ecologica Sinica 43 (2023) 234-244.

- Sayantani Chanda and Dr. T. V. Ramachandra. Appraisal of Rare, Endemic and Threatened medicinal plants of Western Ghats. Lake_symposium 2018.

- Satheeshkumar, P. K., Srinivasan, K. V., Sivadasan, M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2011). Diversity and endemism of flowering plants in the Western Ghats, India. Taiwania, 56(3), 193-215.

- Sangale M. P., Kshirsaga S. R., Shinde H. P. Studies on Floristic diversity of some endangered plant species from Western Ghats of Nasik district, Maharashtra. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, Vol 8, Issue 2; pg 278-286, 2021.

- Sayantani Chanda and Dr. T. V. Ramachandra. Medicinal plants resources in sacred groves of South-western West Bengal. 5th Biodiversity Meet, 2018.

- A. S. Sawant and B. F. Rodrigues. Documentation of Some Medicinal Plant Species from Goa. Advances in Plant Sciences and Biotechnology, 10-16, 2015.

- Sayantani Chanda and Dr. T. V. Ramachandra. Phylogenetic, Morphology and Phenology analysis of Indian Medicinal plants of Eastern region. Lake_symposium 2018. IBM 2nd March, 2019.

- Baragur Neelappa Divakara, M. Srinivasa Rao. Assessment of Floristic composition and Diversity of Goa Forest types. Sep, 2015

- Gurusamy, M., Subramanian, V., & Raju, R. (2022). Diversity and Conservation status of flora in Pilavakkal dam foothills of Western Ghats, Tamil Nadu, India. Indonesian Journal of Forestry Research, 9(2), 215-237.

- Sreekanth G. B., Mujawar S. (2021). Fisheries Sector of Goa: Present Status, Challenges and Opportunities.

- Paramesh, V., Kumar, P., Nath, A. J., Francaviglia, R., Mishra, G., Arunachalam, V., & Toraskar, S. (2022). Simulating soil organic carbon stock under different climate change scenarios: A RothC model application to typical land-use systems of Goa, India. Catena, 213, 106129.

- Ansari, M. A., Mohokar, H. V., Deodhar, A., Jacob, N., & Sinha, U. K. (2018). Distribution of environmental tritium in rivers, groundwater, mine water and precipitation in Goa, India. Journal of Environmental Radioactivity, 189, 120-126.

- Joshi, V. C., & Janarthanam, M. K. (2004). The diversity of life‐form type, habitat preference and phenology of the endemics in the Goa region of the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Biogeography, 31(8), 1227-1237.

- Joshi, V. C., & Janarthanam, M. K. (2004). The diversity of life‐form type, habitat preference and phenology of the endemics in the Goa region of the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Biogeography, 31(8), 1227-1237.

- Deshpande, T. V., & Kerkar, P. (2023). Vulnerability of Mangroves to Changing Coastal Regulation Zone: A Case Study of Mandovi and Zuari Rivers of Goa. Nature Environment and Pollution Technology, 22(1), 339-353.

- Forest Department of Goa (Government of Goa | Official Portal) (WILD LIFE MANAGEMENT | Forest Department (goa.gov.in))

- Champion, H.G. & S.K. Seth (1968). A Revised Survey of the Forest Types of India. Manager of Publicatins, New Delhi, 404pp.

- Cottam, G., and J.T. Curtis. 1956. The use of distance measure in phytosociological sampling. Ecology 37:451-460.

- Ramachandra TV, Chandran MDS, Gururaja KV, Sreekantha (2006) Cumulative Environmental Impact Assessment, Nova Science Publishers,New York, 371 pp

- McElhinny, Chris; Gibbons, Phillip; Brack, Cris; Bauhus, Juergen (2005). "Forest and woodland stand structural complexity: Its definition and measurement". Forest Ecology and Management. 218 (1–3): 1–24.

- India Biodiversity Portal.” India Biodiversity Portal, https://indiabiodiversity.org/document/show/1364. Accessed 14 May 2023.

- IUCN (2009a) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.1. Available online: www.iucnredlist.org.

- Turner, I. M., Corlett, R. T., & James, P. K. (2001). The conservation value of small, isolated fragments of lowland tropical rain forest. Trends in ecology & evolution, 16(12), 613-618.

- Hilty, J. A., Lidicker Jr, W. Z., & Merenlender, A. M. (2006). Corridor ecology: the science and practice of linking landscapes for biodiversity conservation. Island Press.

- IPCC. (2014). Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- https://indiabiodiversity.org/

- Sasidharan, N. (2004) Biodiversity Documentation for Kerala Part 6: Flowering Plants. Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi.

- Venkatachalapathi, A., Sangeeth, T., & Paulsamy, S. (2015). Ethnobotanical informations on the species of selected areas in Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, the Western Ghats, India. J. Res. Biol, 5, 43-57.

- Rao, R. S. (1985). Flora of Goa, Diu, Daman, Dadra and Nagarhaveli.