- Roots : Aerial adventitious roots called stilt roots that spring out from the main trunk provide additional support to the swamp trees in the soft soil. Such roots might become woody and flattened with age, becoming ‘flying buttresses' as in Myristica spp. and Virola surinamensis. Some Malayan species of Myristicas produce stilt roots in swampy conditions and not when they grow elsewhere (Richards, 1952). M. malabarica , a species of wild nutmeg found in the evergreen forests of South Indian Western Ghats often produce stilt roots and flying buttresses, even though it is seldom associated with swamps, indicating its possible origin in the swamps. Apart from the Myristicas , the several flood tolerant species of the Western Ghats, such as Elaeocarpus, Holigarna, Madhuca neerifolia, Pandanus etc. also produce stilt roots.

In many flood-tolerant dicots the original tap root dies and the plants depend on adventitious water roots, which arise from the stem above the flood zone. These roots trap debris and soil and over time build a hummock around the base of the tree, permitting portion of the roots to remain above the general flood level (Hook and Brown, 1973; Coutts and Philipson, 1978; Hook, 1984). Some trees of habitually water-logged soils produce from horizontally growing roots knee like knobby protrusions into the air. At least initially the knees are spongy and apparently provide the underwater roots with air. The knees facilitate gas exchange freely (Cowles,1975). Pond cypress in the US and Semecarpus kathalekanensis, an altogether new species reported from some of the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada (Vasudeva et al ., 2001) have such knee roots.

Loop like roots protrude into the air from the flooded substratum in the swamp dwelling Gymnacranthera canarica of the Western Ghats. These aerial loops, which thicken with age, are studded with enlarged air pores called lenticels.

- Rhizomes : Rhizomes are thick stems buried in the soils as found in many herbaceous plants such as ginger, turmeric etc. Many swamp growing ferns and herbs such as aroids have spongy rhizomes. Pinanga dicksonii, a delicate, shade-loving palm endemic to the Western Ghats, and often found in the vicinity of the Myristica swamps, propagate mainly through rhizomes. Rhizomes, according to Braendle and Crafford (1987), exhibit a much greater range of flood tolerance than roots.

- Physiological adaptations : Roots of swamp species are known to cope up with oxygen deficiency of soil through anaerobic respiration. Through the lenticel studded aerial roots of the swamp plants diffuse out products of anaerobic metabolism, such as ethyl alcohol, acetaldehyde, ethylene etc., the accumulation of which could be toxic to the tissues. Apart from venting out toxic products, lenticels also serve as primary entry points for oxygen into the root zone (Hook and Scholtens, 1978; Davies, 1980; Kozlowski, 1982). In the Myristica swamps of Travancore, Varghese and Kumar (1997) found moderate levels of oxidation of soil by the knee roots. In fact the lenticels lead into a system of intercellular spaces. The roots with such aerated tissues (aernchyma) can grow in anaerobic media and also function well in the transport of ions to the xylem (Drew, 1987).

- Seed germination: Flooded conditions are a challenge to the germination of seeds. Seeds of many swamp plants, however, can remain viable in water for long periods. They do not germinate under water, and their regeneration is usually limited to drought period when the soil surface is exposed. Because of rapid juvenile growth the swamp species extend their foliage as high as possible before the normal flood level returns (Debell and Naylor, 1972; Hook, 1984). At the same time adequate amount of water has to be available for imbibition, subsequent germination and seedling establishment. In places with long dry season, seedling desiccation may be a major obstacle to recruitment. A study in a seasonally dry forest in Panama showed that availability of soil water during the dry season may limit the survival and growth of seedling of Virola surinamensis of Myristicaceae (Khurana and Singh, 2001).

Myristicaceae : the dominant family of the swamps

Myristica swamps are dominated by members of Myristicaceae. A primitive family of flowering plants, Myristicaceae has 18 genera and 300 species. The nutmeg, Myristica fragrans, a native of Mollucas Island, and cultivated widely in the gardens of the Western Ghats, is a well known spice. The members of the family are pantropical, being associated with the rainforests of Asia, Africa, Madagascar, South America and Polynesia. Myristica with 120 species is the largest of the genus; New Guinea has the largest number of species. Virola is major component of the Amazon forests. Knema spp. are found in Southeast Asia and Malaysia (Takhtajan, 1969; Ahmedullah and Nayar, 1986). India has four genera namely Horsfieldia, Gymnacranthera, Knema and Myristica and altogether 15 species. The members occur in the evergreen forests of Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Meghalaya and the Western Ghats. Iryantha and Virola are found in the swamp forests of Venezuela. Apart from the South Indian Western Ghats swamps dominated by Myristicaceae are also reported from New Guinea (Corner, 1976).

The members of Myristicaceae, the world over, share several common features. They are shade-tolerant, evergreen trees with pink or red resinous juice in the bark. The trees have central shaft like main stem producing horizontal branches. The leaves are simple, dark green and alternate. The flowers are small, dull in appearance, either male or female with only one whorl of perianth. The stamens in the male flower together form a central column. The ovary in the female has one chamber and one ovule. The fruits wall is fleshy and fibrous, and when mature splits into two valves exposing a single large seed covered with a bright orange or red juicy cover called aril. The kernel of the seed is rich in starch and oil. Many members of the family, being equipped with aerial roots can endure water-logging (Kuhn and Kubitzki, 1993).

MYRISTICA SWAMPS OF THE WESTERN GHATS

The Western Ghats have three genera and five species of Myristicaceae; all of them are trees associated with evergreen to semi-evergreen forests. Of these Gymnacranthera canarica and Myristica fatua var. magnifica are exclusive to the swamps. M. malabarica is occasional in the swamps and more frequent in the evergreen forests. The other species of trees are M. dactyloides and Knema attenuata. All these are trees endemic to the Western Ghats.

Distribution of Myristica swamps

Any little patch of woods having the presence of G. canarica or M. fatua var. magnifica or both is considered here as a Myristica swamp. Krishnamoorthy (1960) reported Myristica swamp, for the first time, as a special type of habitat from Travancore. These swamps were found in the valleys of Shendurney, Kulathupuzha and Anchal forest ranges in the southern Western Ghats. Champion and Seth (1968) classified such swamps under a newly introduced category ‘Myristica Swamp Forests' under the Sub Group 4C. The northernmost swamp known is associated with a sacred grove in the Satari taluk of Goa (Santhakumaran et al. 1995). However they have not reported M. fatua or G. canarica from the Goa locality. The photographs in their paper, however, are indicative of the presence of G. canarica, thereby meriting the classification of the habitat as a Mytristica swamp.

Varghese and Kumar (1997) differentiate between two types of swamps having Myristicaceae, in the Travancore region: 1. Myristica swamp forest, restricted to below 300 m, fringing sluggish streams. 2. Tropical sub-montane hill valley swamp forest- found as narrow strips of water-logged areas. Whereas the former has M. fatua as well as G. canarica, in the latter, G. canarica is found along with Mastixia arborea and several others. Such bifurcation of these swamps does not have enough justification. The Atlas of Endemics of the Western Ghats (India) by Ramesh and Pascal (1997) shows that G. canarica and M. fatua occur from sea level to 700 m and 1000 m altitudes respectively.

More detailed studies on the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada have been made recently in Uttara Kannada district of central Western Ghats in Karnataka. These swamps are isolated and situated in localities from near sea level to about 450 m altitude (Chandran et al. , 1999; Chandran and Mesta, 2001). This article is based on the Uttara Kannada study.

On the occurrence of Myristica fatua

Myristica swamps of the Western Ghats are in very disjointed state. Most swamps do not have Myristica fatua , but Gymnacranthera is present invariably. Between the Travancore sites (8° to 9°N) and the northernmost site in Uttara Kannada (14°N) Ramesh and Pascal (1997) have shown only a single location, at 12°N for M. fatua . We have found one more site for this species, in a one ha swamp in the Maihme village in the interior of Honavar taluk, in addition to the already known Katalekan site of Malemane village in Siddapur taluk.

Ramesh and Pascal (1997) found more number of locations for the other exclusive swamp species Gymnacranthera , the northernmost location being at 13°N latitude, close to Kudremukh. The very fact that our studies (Chandran and Mesta, 2001) revealed 51 swamps in southern Uttara Kannada, at 14°N lat., all of them new reports for this tree species, highlight the need for making all out search for the Myristica swamps in rest of the South Indian Western Ghats.

The study areas

The Uttara Kannada district, formerly North Kanara (13°52' to 15°30N and 74°05' to 75°5'E), is located towards the centre of the Western Ghats. The district with 10,250 km² of area is one of the most forested in South India with about 70% of the land under forest cover, including forest plantations. Here the Western Ghats seldom exceed 700m in altitude. The district is a maze of steep hills with narrow valleys. Tropical evergreen to semi-evergreen forests form the natural climax vegetation in most of parts of the district which receive 200 to 500 cm of rainfall. Human impact, especially through the last three millennia, has variously modified the natural vegetation, which probably had a network of swamps, into various forms of secondary forests, monoculture plantations, agricultural areas and so many other land uses.

Being very hilly, only about 12% of Uttara Kannada's land area is presently under cultivation. Most hills have, in the pre-colonial and early colonial period passed through phases of slash and burn cultivation by various local communities. Alterations of primary forests, would have in all probability destroyed substantial areas of primeval swamps. Swamps would have as well perished in the fires set on by shifting cultivators who altered through ages, substantial parts of Uttara Kannada's evergreen forests, until the close of the 19 th century, when the British almost put out totally this form of cultivation. Nevertheless the forest alterations detrimental to swamps continued unabated during the state management of forests both during the British and post-British periods. Over 1000 km² of forests have given way to tree plantations. Many valleys were submerged under hydel projects, and forest lands (about 1000 km²) were released for various non-forestry purposes, after the independence. There is very little scope for return of the primary swamps in the Uttara Kannada district which has at least five dry months.

Pre-colonial conservation

Pre-colonial agriculture went hand in hand with community based system of conservation. Most of Uttara Kannada's villages had one or more sacred forests of often several hectares area, known as kans. These kans were patches of evergreen forests with perennial water sources (Chandran and Gadgil, 1993), and some of them could have harboured Myristica swamps as well. The Kathalekan swamp in Siddapur, associated with Myristica fatua, is in the midst of a patch of climax evergreen forest dominated by Dipterocarpus. During the British period the communities lost their hold over the kans, which became the state property. Many kans perished thereafter or lost their identity or were converted into alternative land uses. Of the 51 swamps that we came across in southern Uttara Kannada, 17 of them, although small fragments in size, were sacred groves. They could have been larger in size in the pre-colonial times.

Distribution and size ranges of Myristica swamps

Details regarding Forest Range and village-wise distribution of Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada are given in Table-1 . Except for two swamps in the Mahime village of Honavar taluk all others are situated in Siddapur taluk.

Table 1: Forest range and village-wise distribution of Myristica swamps

of Uttara Kannada.

Forest Range |

Village |

No. of swamps |

Area (m 2 ) |

Range total |

Siddapur |

Malemane |

10 |

27900 |

|

Bidrakan |

1 |

50 |

27950 |

|

Kyadgi |

Hemgar |

3 |

2000 |

|

Kudgund |

7 |

12900 |

||

Hukli |

2 |

2400 |

||

Haadrimane |

6 |

9025 |

||

Havinbil |

1 |

100 |

||

Sovinkoppa |

1 |

4000 |

30425 |

|

Amenhalli |

Harigar |

11 |

17950 |

|

Unchalli |

7 |

10650 |

28600 |

|

Gersoppa |

Mahime |

2 |

11200 |

11200 |

Grand total |

51 |

98175 |

98175 |

Uttara Kannada study shows that nearly half of the 51 swamps fall in the size class of less than 500 m² in area ( Figure-1 )' some of them barely deserve to be called swamps because they fall within 50 to 100 m²- not more than a clump of trees- and with hardly and signs of regeneration of the swamp species. Most swamps are linear formations fringing slow running water courses, within fragments or patches of evergreen forests.

Figure 1. Frequency distribution of Size class (in m 2 ) of Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

1 = <500 |

2 = 500-1000 |

|

3 = 1000-1500 |

|

4 = 1500-2000 |

|

5 = 2000-2500 |

|

6 = 2500-3000 |

|

7 = 3000-3500 |

|

8 = 3500-4000 |

|

9 = 4000-4500 |

|

10 = 4500-5000 |

|

11 = 5000-5500 |

|

12 = 5500-6000 |

|

13 = 6000-6500 |

|

14 = 6500-7000 |

|

15 = 7000-7500 |

|

16 = 7500-8000 |

|

17 = 8000-8500 |

|

18 = 8500-9000 |

|

19 = 9000-95000 |

|

20 = 9500-10000 |

Quantitative sampling of vegetation

We studied the swamps and their surrounding vegetation using a combination of transect and quadrats. Quadrats of 20 m X 20 m were laid along transects of variable length along the linear course of the swamp. Trees (minimum gbh – 30 cm) were enumerated within each quadrat. An inter-quadrat distance of 20 m was normally maintained. The girths of trees were measured and heights estimated. The ground vegetation of the swamps including the regeneration status of trees was studied.

Swamp vegetation

Of the several tree species associated with the Myristica swamps, three were exclusively associated with them: 1. Myristica fatua var. magnifica , 2. Gymnacranthera canarica and 3. Semecarpus kathalekanensis

- Myristica fatua var. magnifica

- Gymnacranthera canarica

- Semecarpus kathalekanensis

It is endemic to the Western Ghats and critically endangered. After the Travancore swamps at 8-9°N lat. this species was known only from a single location in southern Uttara Kannada at 14°17'N lat., in the Malemane village of Siddapur taluk. Ramesh and Pascal (1997) have reported a lone site at 12°N in the Kannur district of Kerala. Our survey revealed one more swamp with this species in the Mahime village of Honavar taluk (Chandran et al ., 1999). Dasappa and Ram (1999) found this species in a swamp in the Hulikal Ghat of Shimoga district.

M. fatua has large evergreen leaves. From the lower part of the tree trunk arise numerous stilt roots, which with age turn into flat and woody structures, sometimes called ‘flying buttresses'. The fruit is large and fleshy and the single large seed is enveloped in an orange aril. We estimated about 250 trees in the district. Since these swamps are under severe threat, habitat-centred conservation of the species is of paramount importance. The seeds having very short viability period germinate and become seedlings only in deeply shaded and wet soil.

A lofty evergreen tree of Myristicaceae, the species is endemic to Western Ghats. Ramesh and Pascal (1997) have recorded 13 locations for Gymnacranthera, the northernmost being at 13°N lat. Therefore our finding regarding its occurrence in all the 51 swamps of southern Uttara Kannada (at 14°N lat.) is significant. In all probability it has isolated occurrence in more northern localities, including in the sacred grove reported from the Satari taluk of Goa by Santhakumaran et al. (1995).

The tree has characteristic loop like breathing roots, protruding out of the water logged soil all around the main trunk. These roots are studded with large air pores or lenticels. These roots are slender and spongy when young, but turn large and woody with age. The seeds of the species have very short viability period and require swampy conditions for germination.

A member of the mango family Anacardiaceae, this evergreen tree with very large simple leaves, attains a height of about 30 m. This tree was earlier identified as Semecarpus travancorica (Chandran et al. , 1999). This has been described as a new species by Dasappa and Swaminath (2000). Population structure and reproductive biology of this critically endangered swamp tree has been investigated by Vasudeva et al. , (2001).

The tree has smooth grayish-brown bark, mottled with numerous prominent lenticels. The bark exudes a black resinous, thick acrid sap from injured portions, which is highly allergic and causes severe burning on the skin. The tree has knee roots which protrude out of the swampy soil all around the tree. The knee roots have prominent lenticels on the surface. Altogether four swamps in Siddapur taluk had small populations of this tree. Adult individuals were found only in three. The leaves are simple and very large attaining lengths of 40-60 cm in adults and almost about one meter in the juveniles. The flowers are small and unisexual. The seeds have very short viability period of less than one week.

The Myristica swamps are also associated with many other species which show tolerance to various degrees of flooding. However these are not swamp exclusive species. Among the trees are evergreens like Calophyllum apetalum, Dipterocarpus indicus, Elaeocarpus tuberculatus, Lophopetalum wightianum and Mastixia arborea. Notable of the ground layer are rare herbs like Alpinia malaccensis, Jerdonia indica, Neurocalyx calycinus and Schumanniatus virgatus. An aroid Lagenandra ovata and Elatostemma lineolatum and Pellionia heyneana, both members of Urticaceae, are abundantly associated with some of the swamps. Pinanga dicksonii , a slender endemic palm of the Western Ghats, grows gregariously in some of the Siddapur swamps enhancing their primeval appearance. |

Plate: Semecarpus kathalekanensis- leaves of the juvenile form |

Notable of the Pteridophytes are Angiopteris evecta, Bolbitis appendiculata, Cyathea nilgiriensis, Osmunda regalis, Pronephrium triphyllum, Selaginella, Pteris, Staenochlaena palustris and Tectaria wigthii.

Dominance of Myristicaceae

Figure 2. Family-wise distribution of tree numbers (based on 37 quadrats of 400 m 2 each) in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

1 = Myristicaceae |

2 = Cornaceae |

|

3 = Anacardiaceae |

|

4 = Clusiaceae |

|

5 = Dipterocarpaceae |

|

6 = Celastraceae |

|

7 = Rutaceae |

|

8 = Myrtaceae |

|

9 = Oleaceae |

|

10 = Arecaceae |

|

11 = Ebenaceae |

|

12 = Lauraceae |

|

13 = Elaeocarpaceae |

|

14 = Flacourtiaceae |

|

15 = Euphorbiaceae |

|

16 = Anonaceae |

|

17 = Meliaceae |

|

18 = Moraceae |

|

19 = Burseraceae |

|

20 = Rhizophoraceae |

|

21 = Rubiaceae |

|

22 = Others |

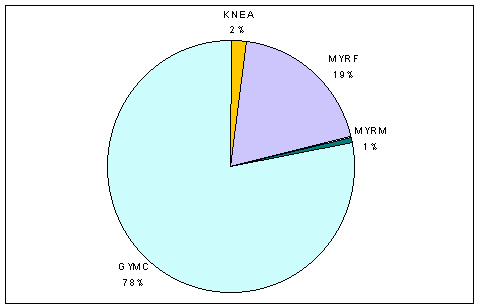

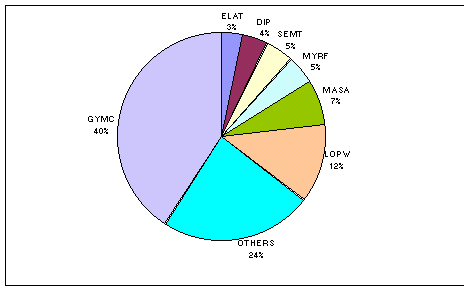

The family-wise distribution of actual number of trees counted in the 37 quadrats of 400 m² each, from the swamps is depicted in Figure 2 . Myristicaceae was the most dominant family of the swamps forming 32% of the total number of trees. Within the Myristicaceae, Gymnacranthera canarica accounted for 78%, followed by Myristica fatua var. magnifica (19%), Knema attenuata (2%) and Myristica malabarica (1%) ( Figure 3) .

Figure 3. Relative composition of tree species within the family Myristicaceae in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

GYMC = Gymnacranthera canarica |

| KNEA = Knema attenuata | |

| MYRF = Myristica fatua var. magnifica | |

MYRM = Myristica malabarica |

|

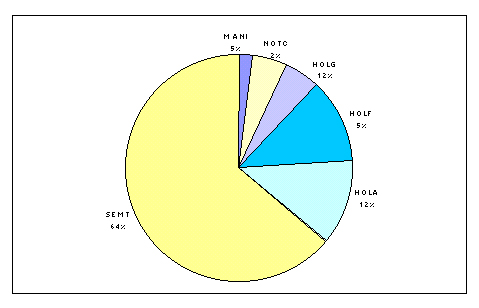

The Cornaceae was represented by a single species Mastixia arborea. Apart from its association with the swamps, this endemic tree was also found sparingly along the streams of the south and central Western Ghats. It was reported to occur up to 1800 m in the southern Western Ghats (Ramesh and Pascal, 1997). The relative proportion of Anacardiaceae associated with the swamps is given in ( Figure 4 ). Notable of the family was the newly reported and critically endangered Semecarpus kathalekanensis. Five of the six members of this family are Western Ghat endemics.

Figure 4. Relative composition of tree species within the family Anacardiaceae in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

SEMT = Semecarpus travancorica |

| HOLA = Holigarna arnottiana | |

| HOLF = Holigarna ferruginea | |

| HOLG = Holigarna grahamii | |

| NOTC = Nothopegia colebrookeana | |

| MANI = Mangifera indica | |

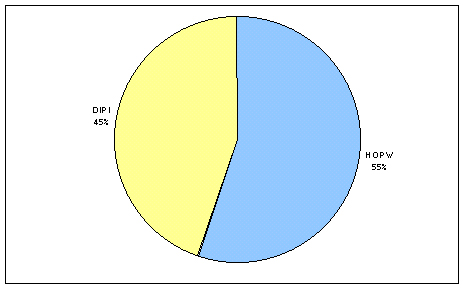

Dipterocarpus indicus and Hopea ponga, both Western Ghat endemics, were found as associates in the areas abutting swamps ( Figure 5) . The former is rare in Uttara Kannada district and notably present only in some of the kan forests, including in the Kathalekan forest, distinguished by the presence of the Myristica swamps.

Figure 5. Relative composition of tree species within the family Dipterocarpaceae in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

DIPI = Dipterocarpus indicus |

HOPW = Hopea wightiana |

|

Basal area and Importance Value Index

The overall mean basal area estimated for one hectare of the swamp was 66 m² for the compared to the adjoining forests where it was 42 m². This shows that the Myristica swamps are relics of climax forests with very mature trees still surviving. G. canarica (40%) contributes major share of the basal area for swamp trees, followed by Lophopetalum wightianum (12%) – see Figure 6 for more details. The importance value index (IVI) for 68 species of trees associated with swamps was obtained by summing the relative density, relative frequency and relative basal area ( Table 2 ).

Figure 6. Relative basal area of trees in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

|

GYMC = Gymnacranthera canarica |

| LOPW = Lophopetalum wightianum | |

| MASP = Mastixia arborea | |

| ELAT = Elaeocarpus tuberculatus | |

| MYRF = Myristica fatua var. magnifica | |

| SEMT = Semecarpus travancorica | |

DIPI = Dipterocarpus indicus |

|

Table 2. Importance value index ( IVI ) of trees in the Myristica swamps of Uttara Kannada.

Trees |

RD |

RF |

RB |

IVI |

Gymnacranthera canarica* |

27.76 |

27.76 |

33.50 |

89.02 |

Mastixia arborea* |

14.94 |

14.94 |

8.50 |

38.37 |

Lophopetalum wightianum |

4.38 |

4.38 |

15.14 |

23.90 |

Myristica fatua var. Magnifica* |

6.98 |

6.98 |

5.66 |

19.63 |

Semecarpus travancorica* |

6.82 |

6.82 |

5.55 |

19.18 |

Dipterocarpus indicus* |

3.41 |

3.41 |

5.18 |

11.99 |

Hopea wightianum* |

4.38 |

4.38 |

1.66 |

10.43 |

Olea dioica |

2.44 |

2.44 |

2.14 |

7.01 |

Dimocarpus longan |

2.76 |

2.76 |

1.38 |

6.90 |

Garcinia gummi-gutta |

2.92 |

2.92 |

0.82 |

6.66 |

Elaeocarpus tuberculatus |

0.97 |

0.97 |

4.06 |

6.01 |

Caryota urens |

1.79 |

1.79 |

0.67 |

4.24 |

Machilus macarantha |

0.32 |

0.32 |

3.58 |

4.23 |

Hydnocarpus laurifolia* |

0.49 |

0.49 |

2.19 |

3.16 |

Holigarna grahamii* |

1.30 |

1.30 |

0.48 |

3.07 |

Syzygium laetum* |

1.14 |

1.14 |

0.24 |

2.52 |

Diospyros candolleana* |

0.97 |

0.97 |

0.18 |

2.13 |

Syzygium hemispericum |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.81 |

2.11 |

Callicarpa tomentosa |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.53 |

1.83 |

Holigarna arnotiana* |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.51 |

1.81 |

Euonymus indicus* |

0.81 |

0.81 |

0.14 |

1.76 |

Syzygium macrocephala* |

0.81 |

0.81 |

0.09 |

1.71 |

Anthocephalus cadamba |

0.16 |

0.16 |

1.37 |

1.69 |

Vapris bilocularis* |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.22 |

1.52 |

Alstonia scholaris |

0.16 |

0.16 |

1.19 |

1.51 |

Knema attenuata* |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.18 |

1.48 |

Garcinia morella |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.14 |

1.44 |

Syzygium cumini |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.73 |

1.38 |

Unidentified - 1 |

0.65 |

0.65 |

0.07 |

1.37 |

Holigarna ferruginea* |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.29 |

1.26 |

Diospyros embryopteris |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.20 |

1.17 |

Canarium strictum* |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.48 |

1.13 |

Myristica malabarica* |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.09 |

1.06 |

Mangifera indica* |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.08 |

1.05 |

Aglaia roxburghiana |

0.49 |

0.49 |

0.07 |

1.05 |

Paramignya monophylla |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.17 |

0.82 |

Myristica dactyloids |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.09 |

0.74 |

Artocarpus hirsutus* |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.06 |

0.71 |

Elaeocarpus serratus |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.04 |

0.69 |

Unidentified - 2 |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.04 |

0.69 |

Flaucortia montana* |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.04 |

0.68 |

Aglaia anamallayana* |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.02 |

0.67 |

Lauraceae sp. - 1 |

0.32 |

0.32 |

0.02 |

0.67 |

Aporosa lyndleyana |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.49 |

Diospyros assimilis* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.17 |

0.49 |

Ficus nervosa |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.13 |

0.45 |

Unidentified - 3 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.11 |

0.44 |

Syzygium zeylanica |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.11 |

0.43 |

Cyclostemon confertiflorus* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.09 |

0.41 |

Lauraceae sp. - 2 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.09 |

0.41 |

Garcinia talbotii* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.08 |

0.41 |

Nothopegia colebrookeana* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.05 |

0.38 |

Cleidion javanicum |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.05 |

0.38 |

Beilschmedia fagifolia* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.05 |

0.37 |

Casearia elliptica |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.04 |

0.37 |

Macaranga peltata |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.04 |

0.36 |

Murraya exotica |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.36 |

Nothapodytes foetida |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.35 |

Unidentified - 4 |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.35 |

Carallia brachita |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.03 |

0.35 |

Cinnamomum malabatrum* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.35 |

Actinodaphne hookeri* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.35 |

Linociera malabarica* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.34 |

Ervatamia heyneana* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.02 |

0.34 |

Agrostistachys longifolia |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

Ixora brachiata* |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

Polyalthia coffeoides |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

Calophyllum tomentosum |

0.16 |

0.16 |

0.01 |

0.34 |

RD : Relative density;

RF : Relative frequency;

RB : Relative basal area;

* : Endemics of Western Ghats

Western Ghat endemism

Western Ghats form one of the biodiversity hotspots of the world, specially rich in endemics. Ramesh et al. (1997) consider Myristica swamps as unique areas at the ecosystem level than at species level. These swamps per se are species poor due to the water-logged conditions. Nevertheless most species found in and around them are endemics. Apart from the members of the Myristicaceae endemism is highly pronounced in Anacardiaceae, Arecaceae (palms), Ebenanceae, Dipterocarpaceae, Cornaceae and several others. The swamps also have various endemic herbs and ferns. A comparison between swamps and adjoining natural forests for tree endemism is given in Table 3. The table shows that the swamps are dominated by Western Ghat endemics.

Table 3: Percentage of tree endemism in the Myristica swamps and adjoining natural forests of Uttara Kannada

% of the endemism of Western Ghats |

||

Locations (Villages in Uttara Kannada) |

Swamps |

Non-swamps |

Malemane |

90 |

60 |

Hemgar |

78 |

33 |

Kudgund |

63 |

40 |

Unchalli |

83 |

55 |

Table 4 provides similar comparison for the ground vegetation. The major reason for decline in endemism in the ground vegetation of the swamps was obviously due to various forms of human disturbances, including the drainage of the swamps for irrigating adjoining farmlands. Cutting of the swamp trees also promotes the arrival of various weeds and non-endemic ground vegetation, obviously due to the changed micro-climatic conditions. The future of the swamps is bleak unless early steps are taken to safeguard the last remnants of these ancient forests from further depredations of humans.

Table 4: Percentage of ground layer endemism in the Myristica swamps and adjoining natural forests of Uttara Kannada

| Locations (villages in Uttara Kannada) | % of ground vegetation endemism of Western Ghats |

|

| Swamps |

Non-swamps |

|

| Malemane | 62 |

70 |

| Hemgar | 49 |

58 |

| Kudgund | 87 |

84 |

| Unchalli | 42 |

68 |

Threats to the freshwater swamps

The world over fresh water swamps are threatened habitats. The extensive swamps of Mississippi and their tributaries in the US are extensively dyked, cleared and most often planted with soybeans and other crops. Similar and other threats such as logging, mining etc are operating in other parts of the world too (Clark and Benforado, 1981; Eric, 1997; Rao, 1994).

A major threat to the Travancore Myristica swamps was their conversion into rice fields (Krishnamoorthi, 1960; Champion and Seth, 1968). Asplenium grevillei, a very rare and threatened species of fern that occured in a swamp of Quilon district of Kerala until recent times had vanished as the swamp was drained and the trees removed (Nair and Nair, 1988). Many have been converted into rice fields, oil palm and teak plantations (Ramesh et al. (1991).

In the Uttara Kannada district most swamps are presumably extinct due to human impacts of various kinds. Palynological studies might be of help in locating some of the past swamps. The pressure is mounting on the last traces of the remaining swamps, due to mainly ignorance about the value and evolutionary significance of these ancient patches of forests, and other human pressures. Areca gardens are gnawing away the swamps with the Myristicas, elements which probably had Gondwanaland origin.

Swamps are perennial sources of water. But draining of the swamps by diversion of the streams into areca gardens or rice fields is a major threat to them. When the swamp becomes seasonal the exclusive swamp species fail to regenerate. Of the 51 swamps we observed in southern Uttara Kannada 17 were facing extinction, having lost their swampiness due to diversion of streams. Yet another 21 swamps were under various types of disturbances such as tree-felling, girdling, burning, clearance of ground vegetation, and reclamation for agriculture. |

Plate: Weed infestation in a Myristica swamp of Siddapur, cleared for agriculture |

Since the early days of Indian independence the evergreen forests, including swamp areas were logged for industrial timbers. The logging activities also included road making, dragging, incidental damages etc. Unfortunately, since Myristica swamps were not reported prior to the 1960's we have no record of the swamps that perished during the logging operations and due to the microclimatic changes after logging.

In the 1970's, during the peak period of commercial extraction of timbers from the evergreen forests of central Western Ghats, even Myristica spp. were leased out to the plywood industry. The light wood of M. fatua was considered useful for packing cases and matches. The wood of G. canarica was also used for packing cases and plywood (Nair and Nair, 1988; Gadgil and Chandran, 1989).

Need for conservation

• Evolutionary importance: The Myristica swamps are priceless possessions for evolutionary biology. With its entanglement of aerial roots, canopy of dark green large leaves, and high degree of endemism, the swamp is one of the most primeval ecosystems of the Western Ghats. With their little known specialized biota, these swamps are virtually live museum of ancient life of great interest to biologists. The swamps of Uttara Kannada occur mostly around the relics of the ancient Dipterocarp forests of Siddapur.

Taxonomists consider Myristicaceae as an archaic one and group it along with the Magnolias, the most primitive of the flowering plants. The present day geographic distribution of the nutmeg family members is considered enough evidence of the origin of the family before the breakup of the Gondawanaland into present day landmasses (Raven and Axelrod, 1974; Thorner, 1974; Terborgh, 1992; Cox and Moore, 1993; Kubitzki, 1993). Takhtajan (1969) finds many archaic and primitive features in the family, and terms it as one of ‘living fossils', which due to some favourable circumstances escaped extinction.

Wherever grow the members of Myristicaceae today- in Amazonia or Africa, New Guinea or Madagascar, Malaysia or India- despite their separation by thousands of kilometers of oceans, they have striking similarity, such as tree habit, evergreen nature, reddish exudation, unisexual flowers, beetle pollination, and fleshy fruit with a single large seed enveloped in a brightly coloured aril. Armstrong and Irvine (1989) consider pollination in Myristica by small beetles as relatively archaic and relictual, as also characteristic of the ancestors of flowering plants or proto-angiosperms. Large-beaked ancient birds such as toucans in tropical South America and hornbills in Africa and Asia are among the dispersers of the seeds of Myristicaceae (Howe, 1983; Kuhn and Kubitzki, 1993; Raman and Mudappa, 1998). Corner considers swampy forests to be the home of angiosperms.

• Watershed value of swamps: Because the bottom of the swamp is at or below the water table, it serves to channel runoff into the groundwater supply, helping to stabilize the water table. During periods of very heavy rains, a swamp can act as a natural flood control device ( Columbia Encyclopaedia , 1978). Standing or slow moving water seeps continuously into the ground, helping to replenish underground water reservoirs called acquifers (Cunningham and Saigo, 1990). The presumed widespread loss of perennial freshwater swamps such as the Myristica swamps, as evidenced by their present day rarity and fragmentation is perhaps a reminder of the progressive desiccation of the Western Ghats. When wetlands such as swamps are drained, filled or otherwise disturbed, their natural water absorbing capacity is lost and surface waters run off quickly, resulting in floods and erosion during the rainy season and dry or nearly dry streambeds the rest of the year.

• Biological value: The swamps could have several species of flora and fauna, which need to be investigated. We are in the dark about the nutrient cycling, mycorrhizal relationships, plant-animal interactions etc. and about the genetics and biochemistry pertaining to the swamps. The swamp has high level of Western Ghat endemism among plants, and probably among animals, most of which are yet unstudied. Some fragments of the last few acres of Myristica swamps of Siddapur shelter the only populations in the world of the newly discovered evergreen tree Semecarpus kathalekanensis.

Lion-tailed Macaque, an endangered primate of the Western Ghats, is associated with the relics of the primary forests in Siddapur having the Myristica swamps and Dipterocapus. Subramanian (2003) recorded for the first time a montypic genus of damsel fly Phylloneura westermanni, earlier from only Nilgiris, Coorg and Wayanad in 1933 by Fraser, from a Myristica swamp of Kathalekan. Several streams from the relic primary forests drain into the Sharavati river, that is very rich in fish species. From the lower catchment area of Sharavati has been recoded 51 species of fresh water species, including a new species Parabatasio sharavatiensis.

• Wild relatives of cultivated plants: The swamps are home to some of the wild relatives of cultivated plants- such as M. fatua, Piper nigrum, Piper hookeri, Garcinia spp., Cinnamomum spp., Zingiber spp. etc.

• Economic value: Although swamps per se are small, the humid environment which they support around favour the growth of many economically important trees, medicinal plants and other plants which support many rural livelihoods. These include Apama siliquosa, Dipterocarpus indicus, Calamus spp., Caryota urens, Garcinia cambogea, Myristica malabarica, Saraca indica, Ochlandra scriptoria etc. Ochlandra is widely used for basket and at weaving especially in southern Western Ghats. Myristicaceae members have much more potential economic value. They are rich in essential oils and biochemicals such as flavonoids, lignins, quinines, phenols etc. Research is under way on the uses of derivatives from the family for their anti-diabetic and anticancer activities, and uses as antioxidants and cosmetics, and in the bio-control of Trypanosoma and fungi (Chandran et al. , 1999).

• Sustaining wildlife: The swamp and its immediate surrounding forests have a number of wild fruit bearing trees. These include Garcinia, Myristica, Syzygium, Holigarna, members of Lauraceae, Meliaceae, Myrtaceae etc. which provide food for many wild mammals and birds. The endangered primate Lion-tailed Macaque has its notable presence in the Siddapur evergreen forests.

Conclusions

Conservation of the swamps with their ancient and unique biota, and associated ecological value, is of paramount importance. The swamps have suffered heavily from ignorance and neglect, in the recent decades, although heir willful conversions into agricultural areas or other alternative uses have taken place through centuries.

Our interactions with the farmers and forest dwellers in the forest belt of southern Uttara Kannada, where the last swamps are fading out almost imperceptibly, are encouraging. They can be easily sensitised about the importance of conservation of the Myristica swamps. Most of the swamp locations are places where the foresters seldom reach, and are therefore more at the mercy of the forest dwellers. If they could be taken as partners in conservation and restoration, through a system of incentives, the swamps will survive. Other swamps safer from human threats will have to be restored through careful planning and manipulations and watershed management. Special efforts should be made to locate more of these swamps lying hidden in the recesses of the South Indian Western Ghats.

Our study has generated some good interest in the Myristica swamps among biologists and conservationists. The forest department of Karnataka State is also keen on protection of these fragmented swamps which hitherto remained ignored or hidden in the hinterlands of the Western Ghats.

Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES) Field Station,

Indian Institute of Science (IISc),

#679/2, Vivek Nagar,

Kumta - 581 343. Uttara Kannada (dist)