| Sahyadri Conservation Series - 11 |

ENVIS Technical Report: 35, February 2012 |

|

AGHANASHINI ESTUARY IN KUMTA TALUK, UTTARA KANNADA - BIOLOGICAL HERITAGE SITE |

|

DECLARATION OF BIOLOGICAL HERITAGE SITE UNDER BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY ACT 2002

Note: The proposal made here is for Aghanashini Estuary Biological Heritage Site in Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. Although the estuary itself is unique in biodiversity and productivity, due to the practical problems that could arise in managing the entire estuary as one unit, two separate core areas are identified within it as Location-1 and Location-2, the former of tremendous importance in Molluscan (bivalves) productivity and the latter of importance for the mangrove ecosystem, which is the core area for biodiversity and productivity. As the estuary is one biologically integrated unit the two locations within it are to be brought under a single Heritage Site Management Committee. The two locations have been described separately for convenience.

1. Identification of Property

- State : Karnataka

- Name of the property : Aghanashini Estuary Biological Heritage Site:

Location I: Bivalve Mudflats

- Exact location : Situated in Kumta taluk of Uttara Kannada

district. Lat. 14.520833-14.539342 N & 74.353754-74.369593 E

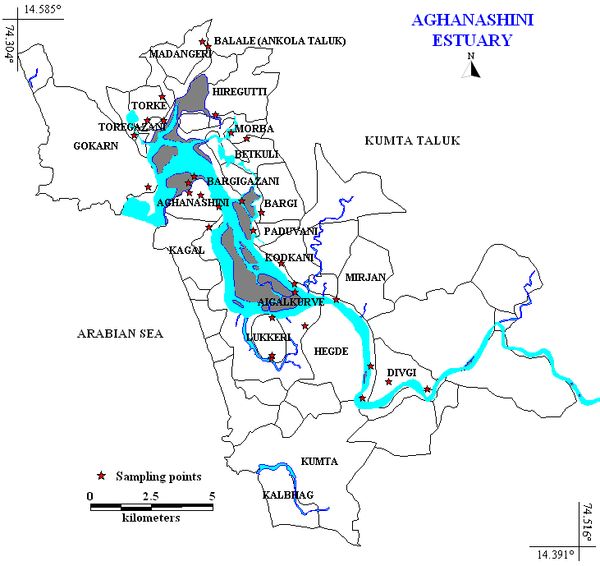

- Maps/plans showing boundary of area proposed: Figures 1, 2 & 3

- Area of Location I : About 229 ha

2. Justification for Declaration

- What is the significance of proposed site (Location-1)?

- A highly productive estuary

Aghanashini River in central Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka originates in the Western Ghats and flows westward towards the Arabian Sea, major part of its course through forested gorges and valleys. Having no dams and no notable industrial establishments or major townships along its banks the river may be considered one of the most pristine ones along the west coast. The River meets the sea in the Aghanashini village of Kumta taluk. The tidal portion, or estuary, towards the river mouth is a flat expanse of water dotted with small islands and narrow creeks. This portion, designated as the Aghanashini estuary, is a highly productive and biologically rich waterscape of coastal Karnataka.

The high productivity of the estuary is due to the following reasons:

- The river water carries large quantity of organic materials from the forests in the catchment area of the Western Ghats and deposits the same in the estuary. The debris becomes important base for food chains operating in the estuary

- The rich mangrove vegetation of the estuary plays significant role in nutrient supply for the diverse faunal community and provide shelter for birds and act as nurseries for many species of fishes and prawns

- The rich bird community (over 120 species)associated with the estuary contributes to the nutrient cycling through their potash and nitrogen rich castings (Details in Annexure I)

- The constant churning and circulation of waters due to flow of fresh water from one side and the tidal influx from the Arabian Sea oxygenates the water and circulates the nutrients

- Significance of bivalve (shellfish) production

Estuaries are ranked among the highest productive ecosystems of the earth. One of the most notable economic and subsistence output of the Aghanashini estuary is the bivalves (Phylum: Mollusca). The meat of these invertebrates is used as a protein rich food by thousands people along the coastal areas of Karnataka and Goa.

Total annual production: Estimated at 22,006 tons, valued at Rs.57.8 million per annum. Most of the of bivalves harvested belong to Paphia malabarica, although six other edible species are also gathered in lesser quantities. Bulk of the bivalve harvest is from mudflats bordering the village by name Aghanashini, close to the mouth of the river (bearing the same name). Collectively these bivalve harvesting areas measure about 229 ha. (Boominathan et al., 2008). It is significant to note that so much of food production is without any investment or supply of feeds by humans. Details are provided in Annexure II.

Constanza et al. (1997) estimated the value of an estuary as Rs.1141600/ha/year. This value is the aggregate of all goods and services such as shrimps, fish, crabs, salt, mangroves, in addition to services such as fish spawning grounds, nutrient cycling, hydrology, flood control, soil protection, sink for carbon etc. It is notable that we have provided for the proposed BHS the value of bivalves only and not the other goods and services.

Crucial role in local economy: Bivalve harvesting is the most important aspect of small scale informal fisheries of Kumta coast, an activity traditionally carried out by even persons from non-fishing communities, for family food security and for sale. Bivalve collection provided direct employment for 2,347 people according to the study referred to Boominathan et al., (2008). Of the harvesters 1,738 collectors were men and 609 were women. The collectors belonged to 19 estuarine villages and congregate in mudflats closer to Aghanashini village during the low tide time for harvesting. The bivalve-linked activities also include minor processing at the site, transportation, collection and sale of empty shells and drying of bivalve meat in small quantities for storage and future use. The calcium rich bivalve shells are used for lime making. The bivalve shell lime is of superior quality for white washing, as fertilizer, prawn feed, poultry feed, production of high grade cement etc.

Food security: Bivalves from the Aghanashini estuary provide excellent protein and mineral rich food for an estimated 198,000 people, especially along the coast. The Indian edible bivalves have protein (5-14%), fats (0.5-3%), calcium (0.04-1.84%), phosphorus (0.1-0.2%) and iron (1-29 mg/100 g of fresh weight) – CSIR (1962).

Ecosystem richness and productivity: The abundant annual production of edible bivalves reflects the rich biodiversity of the estuary in general, which also has around 150 species of fishes, 120 species of birds, 13 species of mangroves, numerous mangrove associates and many more species of lower plants. Organic debris from the bio-diverse community of the estuary itself as well as that brought into the estuary from the Western Ghat forests collectively contributes towards the high production of bivalves

- Why the declaration is proposed? Give justification

The proposal is put forward to declare the major bivalve gathering area of 229 ha as part of (Location-1) of Biological Heritage Site due to the following reasons.

- The bivalve rich area mentioned is the culmination of numerous food chains in the estuary and beyond from the Western Ghats from where nutrients reach the estuary through the river

- The local population has strong cultural bonds with the river, which they treat as Goddess. A long history of human association with the river can be traced, as integral part of people’s culture and livelihood activities such as fishing, fish and prawn culturing, mangrove planting and utilization, transportation, estuarine rice farming, salt making etc.

- The edible bivalve rich mudflats of Aghanashini may be considered as unique, ecologically fragile areas, as their productivity is due to their location towards the river mouth, at appropriate flooding depth during high tides, suitable salinity ranges, and accumulation of a huge quantity organic debris.

- Several aquatic and terrestrial bird species, including migrant species use the bivalves and other organisms of nutrient rich bivalve beds as their food.

- The site recommended for consideration as BHS is not covered under Protected Area network under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 as amended

- No village community has exclusive jurisdiction over the proposed area, although bivalve gatherers assemble here from 19 estuarine villages.

- Bivalve gathering, just like fisheries, has been a subsistence and economic activity from pre-historical times. Unlike fisheries the bivalve gathering is not an activity that needs high skills. It belongs to the sector of ‘informal fisheries’. The bivalve production area and activity of gathering and utilization may be considered a common heritage of the people of Aghanashini estuary.

- As such the bivalve collection activity is not regulated by any norms made by local communities. It is an unregulated, open to all economic activity engaged in by people, irrespective of caste and community. The activity was carried out traditionally on sustainable basis, more to cater local needs. Over the last few years large scale transportation of bivalves especially to Goa market has resulted in local famine and raises question of sustainability of the resource.

- As the bivalve harvesting areas are totally unprotected by any laws from any destructive type development activity or any other kind of disturbances that might happen in the future, in the very site or in any adjoining areas, that could adversely affect the food web of the estuary, it has become necessary to bring such critical areas under Location-1 of ‘Aghanashini Biodviersity Heritage Site’.

- As there is involved here an issue of common resource being used from generations by a set of villages, the proposed property is beyond the jurisdiction of any single Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC) or village panchayat. Section 6a of the Guidelines for selection and management of Biodiversity Heritage Sites (National Biodiversity Authority, 2009) states: “Wherever the BHS extends to more than one local bodies, the management of the BHS shall be the responsibility of the Biodiversity Heritage Site Management Committee ….. approved by the SBB”. Here therefore, the State Government’s role will come into play in the process of declaration, management and monitoring.

- Threat if any (give details)

For generations together the edible bivalve production areas adjoining Aghanashini village were used sustainably by the village communities as production has been abundant and the demand was mainly local. However in the recent years the demand has shot up from outside markets, especially from Goa, causing unprecedented over-harvesting. As many village communities are traditionally associated with bivalve gathering in the same production areas it is beyond the jurisdiction of any single gram panchayat or the local BMC to regulate harvests within sustainable limits. This situation could spell doom to the sustainability of the resource within few years. Further, the estuary is likely to be affected by various developmental interventions in the absence of any biodiversity centred, state sponsored governance.

3. Description

Present status of conservation

Need for conservation was not felt until recent years, when demand for bivalves as food was more local than from outside. As resource was abundant and extraction pressures limited to sustainable limits there was no need to adopt any special measures of conservation. But such need has arisen now due to over-exploitation for catering to outside markets.

4. Management

- Ownership: The part of estuary producing huge quantity of edible bivalves is under the jurisdiction of the Government of Karnataka; no private agency or village panchayat has special rights over the 229 hectares of Location-1 of the proposed BHS.

- Legal status: proposed area comes under the ownership of the Government of Karnataka

- Agency to manage the site after declaration: The ‘Guidelines for Selection and Management of Biodiversity Heritage Sites’ (http://nbaindia.org/wb_day.htm) states under Section 6 (only relevant clauses presented here):

- Wherever the BHS extends to more than one local bodies, the management of the BHS shall be the responsibility of the Biodiversity Heritage Site Management Committee constituted by the BMC or other local institutions linked to the local bodies in case BMC does not exist, and approved by the SBB.

- The committee responsible for the management of the BHS shall include representatives of all sections of local communities, and in particular those most dependent on the natural resources as also those who have been traditionally conserving the area.

- It shall be responsibility of the BMC/BHS Management Committee to prepare and implement a management plan for the BHS which should cover a period of five to ten years

- SBBs will then recognize and facilitate the implementation of the final management plan. Such facilitation shall include direction to all relevant government departments to assist the communities in implementation, including through appropriate changes in their plans and schemes, to eliminate biodiversity-damaging practices and to fully enable and empower the communities in conserving biodiversity. Where necessary orientation programmes shall be organized for such departments and NGOs.

- Any project/activity to be implemented by government or any other agency, which is likely to have adverse impact on the BHS may be avoided.

- Restriction in form of regulating the use of the resources may be warranted in some cases and such restriction shall be totally voluntary on the part of the community.

- Name, designation and address of responsible person/institution for contact:

(common for Location -1 & Location – II of proposed BHS)

- Sources of expertise : Centre for Ecological Sciences (Indian Institute of Science),

Field Station, Viveknagar, Kumta- 581343

5. Factors Affecting the Site

- Pressures affecting the site (Encroachment, Agriculture etc.): nil

- Environmental pressures: Getting subjected to unregulated exploitation, due to non-sustainable harvests of late

- Visitor/tourism pressures: nil

6. Documentation

- Photographs : Photographs for Location-1attached

- Existing site management plans if any: ‘Snehakunja’, Kasarkod, an important local NGO had conducted programmes for estuarine communities on CRZ awareness, mangroves, need for sustainable harvests of bivalves etc.

7. Opinion of other concerned stakeholders: Stakeholders (local fishing communities, other bivalve gatherers and traders) would welcome introduction of sustainable management system

8. Details of disputes if any on the site: Nil

9. General remarks if any: Declaration of Location-I as part of BHS and formulation of appropriate management plans for bivalve harvests, in combination with Location- 2, mangrove area will have good positive effects on the mollusk habitat and production and thereby ensure livelihoods and food security of the local communities.

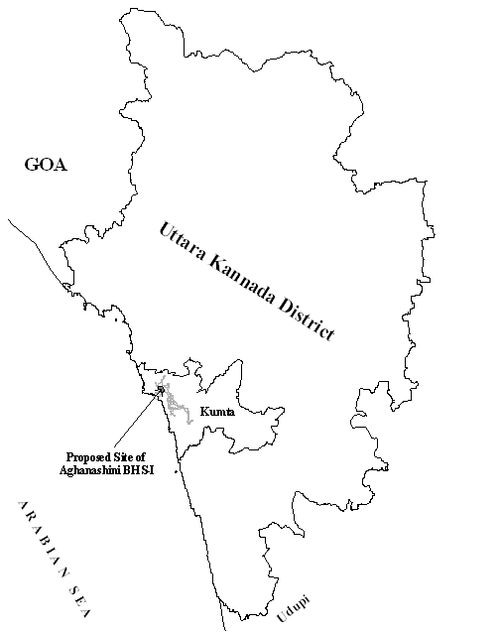

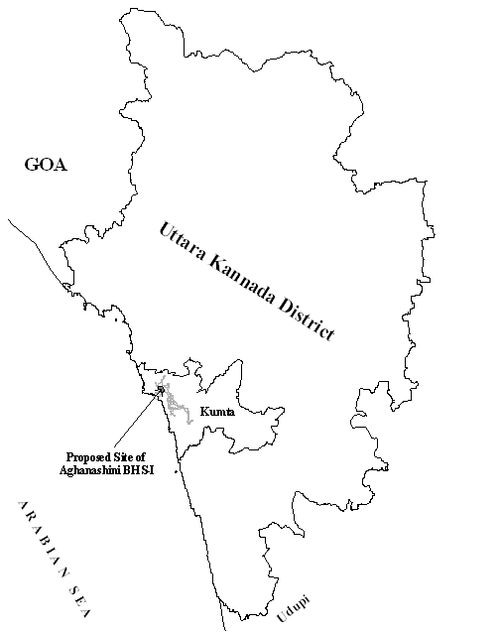

Figure 1: Uttara Kannada District Showing Location of Proposed Aghanashini Bivalve Biodiversity Heritage Site

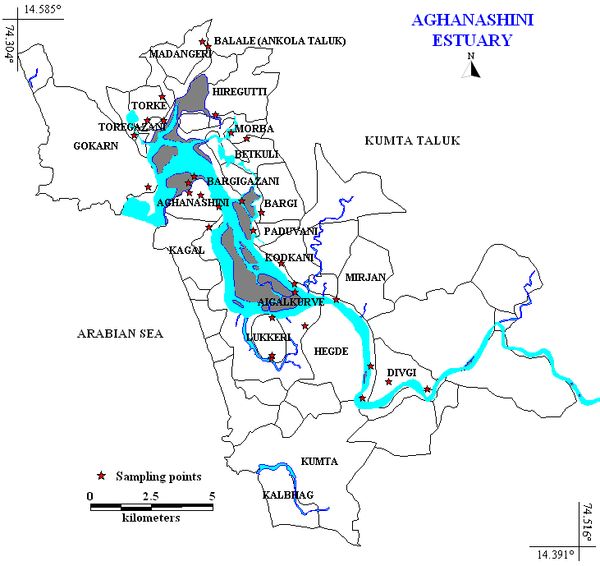

Figure 2: Proposed Aghanashini Biodiversity Heritage Site in the Estuary

Figure 3: Aghanashini River Estuary with surrounding villages

BHS Location I

1. Bivalve collection in exposed mud-flats

2: Using canoes for bivalve collection and transportation

3. Women collecting edible bivalves

4. View of edible bivalves on nutrient rich mudflats

5. Bivalve cleaning and sorting- a major activity of women

6. Bivalves packed for transportation to Goa

DESCRIPTION OF LOCATION- 2 OF AGHANASHINI ESTUARY BHS

1. Identification of Property

- State : Karnataka

- Name of the property : Aghanashini River Mangrove Biodiversity Heritage Site

- Exact location : Situated in Kumta taluk of Uttara Kannada district.

Lat. 14.52083-14.53934 N to 74.35375-74.36959 E

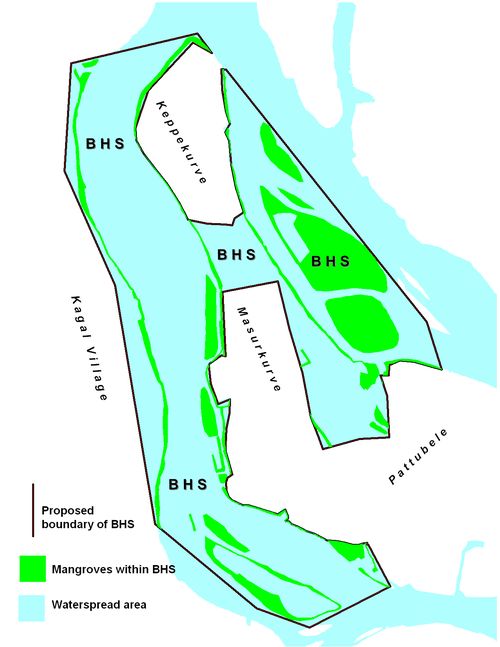

- Maps/plans showing boundary of area proposed: Figures 1, 2 and 4

- Area of site proposed for declaration : About 67 ha

2. Justification for Declaration

- What is the significance of proposed site?

- Aghanashini River in central Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka originates in the Western Ghats and flows westward towards the Arabian Sea, major part of its course through forested gorges and valleys. Having no dams and no notable industrial establishments or major townships along its banks the river may be considered one of the most pristine along the west coast. The River joins the sea in the Aghanashini village of Kumta taluk. The tidal portion, or estuary, towards the river mouth is a flat expanse of water dotted with small islands and narrow creeks.

- Through millennia the estuary and its environs formed the lifeline of the people and constitute a major cultural and historical heritage of the west coast. It was known as a rice bowl in the historical times and rice surplus was transported through water crafts to other regions. The Mirjan fort on the bank of the estuary built by Bijapur Sultans and the ruins of Aghanashini fort on a hill towards the river mouth giving a commanding view of the sea, the estuary and the Western Ghats are testimonials for the historical and cultural importance of the region. Spices grown in the hinterlands of Western Ghats were traded through the estuary during the European period and earlier to it. Gokarna on its shores has been, from time immemorial, a great place of pilgrimage. Before the road networks came the estuary was a major route for transportation of pilgrims. The beaches dotting the coastline of Gokarna are today well known places of tourism. The picturesque estuary with flourishing mangrove vegetation, its rich birdlife, and traditional way of life of the people need to be protected as a cultural heritage and draw for tourism.

- The estuary is a highly productive and biologically rich waterscape of coastal Karnataka. Whereas hundreds of families in the shore villages have direct dependence on it for their livelihoods through activities related to fishing, agriculture, collection of edible bivalves and crabs, shrimp aquaculture, traditional fish farming in the gazni rice fields, bivalve shell mining, salt production, sand removal, water transportation etc. scores of consumers in the estuarine villages and in places far away are benefited by the productivity of the estuary, of which the mangroves constitute the heart. The high productivity of the estuary is due to the following reasons:

- The river water carries large quantity of organic materials from the forests in the catchment area of the Western Ghats and deposits the same in the estuary. The debris becomes important base for food chains operating in the estuary and beyond in the offshore waters of the sea

- The rich mangrove vegetation has significant role in food supply for the diverse faunal community. The mangrove swamp acts as food rich and protective nurseries even for many species of marine fishes and prawns, which lay eggs in the swamp.

- The rich bird community (over 120 species, about half of them winter visitors )associated with the estuarine ecosystem contributes substantially to the nutrient cycling through their potash and nitrogen rich castings

- The constant churning and circulation of waters due to flow of fresh water from one side and the tidal influx from the Arabian Sea oxygenates the water and circulates nutrients.

- Why the declaration is proposed? Give justification

- Importance of mangroves: Mangroves are in the heart of estuarine ecosystem and productivity. Their influence is pronounced not only in the estuaries but also extends far into the offshore areas. Tropical estuaries are ranked among the top productive ecosystems of the world, at par with the coral reefs. The major reason for their productivity is attributed to the mangrove vegetation. There are also other reasons for ranking mangroves high in the conservation circles.

- Mangroves contribute nutrients to the estuarine-marine ecosystem through litter-fall that turn into nutrients eventually. These nutrients contribute significantly towards food web and productivity of the estuary and the coastal sea. The detritus and filter feeding organisms like bivalves contribute substantially to the income and food of the local people. People engaged in bivalve trade and consumers far away are also benefited. The bivalve shell gathering is a major, estuary based enterprise providing direct employment for about 600 persons and many more in associated trade and production of goods using shells such as poultry feed, cement, shell lime, paint, fertilizers etc. The annual output of shells from Aghanashini estuary is estimated to be around 100,000 tons worth Rs.5-6 crores. Fishermen report of good catch of fish closer to mangrove patches than elsewhere. Details are provided in the Annexure II.

- Mangroves act as nursery for fishes and prawns. Many sea fish visit nutrient rich mangrove area for laying eggs so that the juveniles grow amidst abundance of food before they leave for the sea. Resident estuarine fishes also take benefit of the mangrove areas for their food and breeding. The mangroves with their entanglement of roots making a dense impenetrable cover provide a safe place for fishes and prawns securing them from predators. The fishermen also do not cast their nets within the mangrove areas due to the physical obstacles created by the root network.

- Mangroves of Aghanashini provide good roosting place for many species of birds,which find rich food supply in the estuary apart from shelter provided by the mangroves. More than 120 species of birds, half of them migrants, have been recorded (Annexure-1. for recently observed birds) Mangroves protect the islands and mainland from erosion and trap soil and debris that come along with the run-off of the rainy season.

- Traditionally the local farmers used to plant mangroves alongside the earthen embankments of their gazni rice field cum fish farming areas. These mangroves helped in stabilizing the bunds from erosion due to tides and waves and torrential rains of the region. Ever-since the Government built permanent embankments in the estuaries to protect the rice fields the practice of planting mangroves by the locals almost waned out. Nevertheless the Forest Department, during the last one decade raised mangroves in large areas of the estuary. When fully grown these mangroves will make the estuary a haven for birds, increase productivity of the estuary in terms of fish, prawns, crabs, bivalves, oysters etc.

- In the heart of the mangrove enriched estuarine centre is a small uninhabited island which is the abode of ‘Babrudevaru’, the guardian deity of the estuary. The deity is worshipped by people from all the estuarine villages who have strong cultural bonds with the deity. A stretch of mangrove forest dominated by the several ancient trees of Avicennia officinalis is considered so sacred that no one should step inside it wearing footwear. Numerous birds, both migratory (during winter) and resident ones are associated with this sacred kan forest.

- The huge production of edible bivalves in the mudflats adjoining Aghanashini river mouth, although some kilometers away from the proposed mangrove heritage site, owe their productivity to the rich input of detritus from mangroves in addition to the organic matter input brought into the estuary from the Western Ghats.

- The site recommended for consideration as Location- II of BHS is not covered under Protected Area network under the Wildlife Protection Act 1972 as amended.

- No village community has exclusive jurisdiction over the proposed area, nor the Forest Department has any legal rights over there, in spite of the Department being responsible for enriching the estuary with mangroves for the last one decade and conserving it. The mangroves do not come under the Reserved Forest and are vulnerable to damages in the future in the absence of any formal protective measures. Their continued existence has to solely depend on the levels of awareness among the public and the constant vigil that the Department has to keep. Therefore the BHS status can be justified.

- Any decline in mangroves will have severe adverse consequences not only on mangroves but also on the estuarine ecosystem and productivity as a whole; both goods and services from the estuary, will be adversely affected by such contingencies.

- There is involved here an issue of common property resources, beyond the jurisdiction of any single Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC) or village panchayat. Section 6a of the Guidelines for selection and management of Biodiversity Heritage Sites issued by the National Biodiversity (2009) Authority states: “Wherever the BHS extends to more than one local bodies, the management of the BHS shall be the responsibility of the Biodiversity Heritage Site Management Committee ….. approved by the SBB”. Here therefore, the State Government’s role will come into play in the process of declaration, management and monitoring.

- Threat if any (give details)

The estuarine farmers were aware of the importance of mangroves in protecting the earthen bunds of their estuarine rice fields locally known as gaznis. Their practice from time immemorial was to raise mangrove trees alongside the gazni bunds. When the Government constructed permanent embankments for the gaznis to ensure better protection from salt water inundation on a permanent basis, the awareness pertaining to the importance on the role of mangroves dwindled among the local population. The growth of shrimp farming as an enterprise resulted in the creation of numerous aqua-cultural ponds, very often destroying the mangrove vegetation in the process. Such degradation of the mangroves continued until the end of the last century, until the Forest Department came in a big way to restore mangroves, by planting over a million saplings during the last one decade. As a permanent management mechanism for the mangroves is wanting this precious ecosystem any time in future is likely to be affected, to meet demand for timber and firewood from locals as well as outside. Further, in the absence of any formal protective mechanism the mangrove ecosystem stands to be affected by increasing developmental pressures in the densely populated coastal region.

3. Description

- Present status of conservation

As the Forest Department is taking constant care of the mangroves and creating awareness among the local communities, the spread and growth of mangrove community, not only in the proposed BHS but also elsewhere in the estuary, presently is remarkable.

4. Management

- Ownership: The part of estuary proposed under Mangrove Biodiversity Heritage Site is under the jurisdiction of the Government of Karnataka; no private agency or village panchayat has special rights over the mangrove areas proposed for BHS. The prawn farms or privately owned rice fields adjoining the mangrove areas have been excluded from the purview of the BHS. No gram panchayat boundary extends into those parts of the estuary proposed to be under the mangrove BHS.

- Legal status: proposed area comes under Government of Karnataka

- Agency to manage the site after declaration: The ‘Guidelines for Selection and Management of Biodiversity Heritage Sites’ (http://nbaindia.org/wb_day.htm) states under Section 6 (only relevant clauses presented here):

- Wherever the BHS extends to more than one local bodies, the management of the BHS shall be the responsibility of the Biodiversity Heritage Site Management Committee constituted by the BMC or other local institutions linked to the local bodies in case BMC does not exist, and approved by the State Biodiversity Board.

- The committee responsible for the management of the BHS shall include representatives of all sections of local communities, and in particular those most dependent on the natural resources as also those who have been traditionally conserving the area.

- It shall be responsibility of the BMC/BHS Management Committee to prepare and implement a management plan for the BHS which should cover a period of five to ten years

- SBBs will then recognize and facilitate the implementation of the final management plan. Such facilitation shall include direction to all relevant government departments to assist the communities in implementation, including through appropriate changes in their plans and schemes, to eliminate biodiversity-damaging practices and to fully enable and empower the communities in conserving biodiversity. Where necessary orientation programmes shall be organized for such departments and NGOs.

- Any project/activity to be implemented by government or any other agency, which is likely to have adverse impact on the BHS may be avoided.

- Restriction in form of regulating the use of the resources may be warranted in some cases and such restriction shall be totally voluntary on the part of the community.

- Name, designation and address of responsible person/agency for contact:

- The Western Ghats Task Force, Government of Karnataka

- The Honavar Forest Division, Karnataka Forest Department

- The Centre for Ecological Sciences (Indian Institute of Science), Field Station, Viveknagar, Kumta

5. Factors Affecting the Site

- Pressures affecting the site (Encroachment, Agriculture etc.): nil

- Environmental pressure: Presently not significant

- Visitor/tourism pressures: nil

6. Documentation

- Photographs : attached

- Existing site management plans if any: Forest Department, Honavar Division carried out many programmes among local people to develop positive attitude towards mangrove ecosystem. ‘Snehakunja’, Kasarkod had conducted programmes for estuarine communities on CRZ awareness, mangrove planting, need for sustainable harvests of bivalves etc. The Centre for Ecological Sciences (IISc) is conducting Carrying Capacity Studies in the estuary.

7. Opinion of other concerned stakeholders: Stakeholders (local fishing communities, and farmers) would welcome BHS status and introduction of sustainable management system

8. Details of disputes if any on the site: Nil

9. General remarks if any: Declaration of BHS and formulation of appropriate management plans will strengthen mangrove ecosystem that could benefit the goods and services from the estuary substantially which will promote goodwill of the local communities towards such a precious heritage ranked among the highest productive ecosystems of the earth.

Date:

Place: Signature of proposer

References

- Boominathan, M., Chandran, MDS & Ramachandra, TV. 2008. Economic valuation of bivalves in the Aghanashini estuary, West Coast, Karnataka. ENVIS Technical Report 3, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore.

- Constanza, R. et al. 1997. The valuation of world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature, 387: 253-260.

- CSIR 1962. The Wealth of India: Raw materials Vol. VI, National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources, CSIR, New Delhi.

- National Biodiversity Authority. 2009. Guidelines for Selection and Management of Biodiversity Heritage Sites (http://nbaindia.org/wb_day.htm)

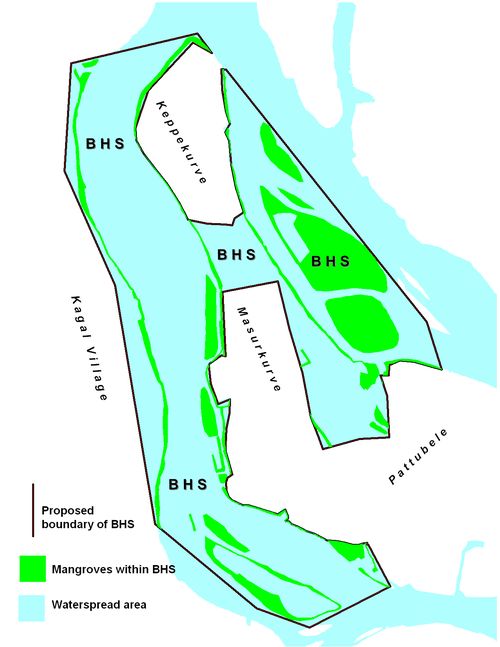

Figure 4: Proposed demarcation for BHS Location 2 showing mangrove areas

in Aghanashini Estuary

Photographs of Mangroves in Location II

1. Root entanglement of Avicennia officinalis

2. Hanging seedlings of Rhizophora mucronata

3. A mangrove sacred grove in Masurkurve, Location-2

4. Transporting grass from mangrove swamp

5. A high density mangrove plantation in the estuary

| Annexure-1: BIRDS OF AGHANASHINI ESTUARY IN KUMTA TALUK OF UTTARA KANNADA |

| |

|

|

| SN |

SCIENTIFIC NAME |

COMMON NAME |

| 1 |

Pavo cristatus |

Indian peafowl |

| 2 |

Vanellus indicus |

Redwattled lapwing |

| 3 |

Streptopelia chinensis |

Blossomheaded parakeet |

| 4 |

Psittacula cyanocephala |

Indian spotted dove |

| 5 |

Loriculus vernalis |

Indian loriquet |

| 6 |

Eudymamys scolopacea |

Indian koel |

| 7 |

Cetropus sinensis |

Crow pheasnat |

| 8 |

Cypsiurus parvus |

Indian palm swift |

| 9 |

Hemiprocne longipennis |

Crested tree swift |

| 10 |

Alcedo atthis |

Small blue kingfisher |

| 11 |

Pelargopsis capensis |

Brownheaded storkbilled kingfisher |

| 12 |

Halcyon smyrnensis |

Whitebreasted kingfisher |

| 13 |

Merops leschenaulti |

Chestnut-headed bee-eater |

| 14 |

Merops orientalis |

Small green bee-eater |

| 15 |

Anthracocerus coronatus |

Malabar pied hornbill |

| 16 |

Megalaema viridis |

Small green barbet |

| 17 |

Dinopaeum benghalense |

Malabar goldenbacked woodpecker |

| 18 |

Hirundo smithii |

Indian wiretailed swallow |

| 19 |

Hirundo daurica |

Himalayan striated swallow |

| 20 |

Lanius schach |

Rufousbacked shrike |

| 21 |

Oriolus xanthornus |

Indian balackheaded oriole |

| 22 |

Acridotheres tristis |

Indian myna |

| 23 |

Acridotheres fuscus |

Indian jungle myna |

| 24 |

Dendrocitta vagabunda |

Indian treepie |

| 25 |

Corvus macrorhynchos |

Indain jungle crow |

| 26 |

Coracina novaehollandiae |

Indian large cuckoo shrike |

| 27 |

Aegithina tiphia |

Peninsular Indian iora |

| 28 |

Pycnonotus jocosus |

Redwhiskered bulbul |

| 29 |

Pycnonotus cafer |

Redvented bulbul |

| 30 |

Muscicapa tickelliae |

Tickell's blue flycatcher |

| 31 |

Orthotomus sutorius |

Indian tailorbird |

| 32 |

Acrocephalus dumetorum |

Blyth's reed warbler |

| 33 |

Phylloscopus trochiloides |

Greenish reed warbler |

| 34 |

Phylloscopus occipitalis |

Largecrowned leaf warbler |

| 35 |

Copsicus saularis |

Indian magpie robin |

| 36 |

Motacilla maderaspatensis |

Large pied wagtail |

| 37 |

Indian purple sunbird |

Nectarinia asiatica |

| 38 |

Bulbulcus ibis |

Cattle egret |

| 39 |

Erymopterix grisea |

Ashycrowned pinchlark |

| 40 |

Galerida malabarica |

Malabar crested lark |

| 41 |

Alauda gulgula |

Indian small skylark |

| 42 |

Corvus splendens |

Indian housecrow |

| 43 |

Pycnonotus luteolus |

Whitebrowed bulbul |

| 44 |

Anthus novaeseelandiae |

Richard's pipit |

| 45 |

Nectarinia zeylonica |

Purplerumped sunbird |

| 46 |

Ploceus philippinus |

Indian baya |

| 47 |

Ardeola grayii |

Pond heron |

| 48 |

Vanellus malabaricus |

Yellow-wattled lapwing |

| 49 |

Turdoides affinis |

Whiteheaded babbler |

| 59 |

Motacilla cinerea |

|

| 51 |

Psittacula kramerii |

Roseringed parakeet |

| 52 |

Apus affinis |

Indian house swift |

| 53 |

Anas acuta |

Pintail |

| 54 |

Milvus migrans |

Paraih kite |

| 55 |

Haliaster indus |

Brahminy kite |

| 56 |

Coracias benghalensis |

Indian roller |

| 57 |

Hirundo rustica |

Eastern swallow |

| 58 |

Saxicola torquata |

Indian collared bushchat |

| 59 |

Accipitor badius |

Indian shikra |

| 60 |

Haliaeetus leucogaster |

Whitebellied sea eagle |

| 61 |

Columba livia |

Blue rock pigeon |

| 62 |

Merops phillippinensis |

Small green bee-eater |

| 63 |

Sturnus pagodarum |

Blackheaded myna |

| 64 |

Prinia socialis |

Ashy wren warbler |

| 65 |

Phyllacrocorax niger |

Little cormorant |

| 66 |

Ardea cinerea |

Grey heron |

| 67 |

Ardea alba |

Large egret |

| 68 |

Butrides stiratus |

Little green heron |

| 69 |

Egretta intermedia |

Smaller egret |

| 70 |

Anas quequdula |

Bluewinged teal |

| 71 |

Circus aeruginosus |

Marsh harrier |

| 72 |

Falco tinnunculus |

European kestrel |

| 73 |

Lonchura malacca |

Blackheaded muniya |

| 74 |

Chardarius dubius |

European little ringed plover |

| 75 |

Tringa glareorla |

Spotted sandpiper |

| 76 |

Ceryle rudis |

Indian pied kingfisher |

| 77 |

Hirundo daurica erythropigea |

Indian redrumped swaloow |

| 78 |

Arocephalus stentorius |

Indian great reed warbler |

| 79 |

Anthus campus |

Tawny pippit |

| 80 |

Motacilla flava |

Greyheaded yellow wagtail |

| 81 |

Motacilla alba |

Grey wagtail |

| 82 |

Egreta gularis |

Indian reef heron |

| 83 |

Nycticorax nycticorax |

Night heron |

| 84 |

Tadorna ferruginea |

Brahminy duck |

| 85 |

Anas crecca |

Common teal |

| 86 |

Aquila cranga |

Greater spotted eagle |

| 87 |

Pluvialis squatarola |

Grey plover |

| 88 |

Pluvialis dominica |

Golden plover |

| 90 |

Charadrius leschenaultii |

Large sandplover |

| 91 |

Charadrius alexandrianus |

Kentish plover |

| 92 |

Charadrius mongolus |

Pamir's lesser sand plover |

| 93 |

Numenius phaeopus |

Whimbrel |

| 94 |

Numenius arquata |

Eastern curlew |

| 95 |

Tringa totanus |

Eastern redshank |

| 96 |

Tringa stagnatalis |

Marsh sandpiper |

| 97 |

Tringa nebularia |

Greenshank |

| 98 |

Calidris minima |

Little stint |

| 99 |

Calidris testacea |

Curlew sandpiper |

| 100 |

Recurvirostrata avocetta |

Avocet |

| 101 |

Glaroeola lactea |

Small Indian pratincole |

| 102 |

Larus brunnicephalus |

Brownheaded gull |

| 103 |

Larus ridibundus |

Blackheaded gull |

| 104 |

Chlidonias hybridus |

Indian whiskered tern |

| 105 |

Halcyon pileata |

Black-capped kingfisher |

| 106 |

Sturnus roseus |

Rosy pastor |

| 107 |

Anhus novaeseelandiae rufulus |

Indian paddyfied pippit |

| 108 |

Motacilla alba |

Indian white wagtail |

ANNEXURE -2 : Details of data collected on bivalves and bivalve collectors

Table 1: Village-wise estimated number of bivalve collecting (BC) households (HH) and number of individuals involved in bivalve harvesting

| Village |

No. of HH** |

BC HH |

% of BC HH |

BC men |

BC women |

Total BC persons |

| Hiregutti |

596 |

1 |

0.17 |

1 |

|

1 |

| Bargigazani |

14 |

5 |

35.71 |

5 |

|

5 |

| Aigalkurve |

120 |

5 |

4.17 |

2 |

6 |

8 |

| Bargi |

359 |

7 |

1.95 |

7 |

4 |

11 |

| Paduvani |

331 |

13 |

3.93 |

3 |

11 |

14 |

| Balale |

213* |

10 |

4.69 |

14 |

|

14 |

| Betkuli |

316 |

22 |

6.96 |

25 |

|

25 |

| Lukkeri |

280 |

32 |

11.43 |

|

34 |

34 |

| Kodkani |

407 |

29 |

7.13 |

25 |

10 |

35 |

| Hegde |

1311 |

31 |

2.36 |

29 |

19 |

48 |

| Kagal |

711 |

33 |

4.64 |

44 |

9 |

53 |

| Madangeri |

279 |

20 |

7.17 |

56 |

|

56 |

| Morba |

180 |

34 |

18.89 |

81 |

10 |

91 |

| Toregazani |

38 |

38 |

100 |

69 |

28 |

97 |

| Mirjan |

630 |

89 |

14.13 |

85 |

94 |

179 |

| Torke |

261 |

72 |

27.59 |

158 |

26 |

184 |

| Gokarn |

2,532 |

98 |

3.87 |

205 |

22 |

227 |

| Divgi |

524 |

323 |

61.64 |

237 |

203 |

440 |

| Aghanashini |

579 |

340 |

58.72 |

692 |

133 |

825 |

| Total |

9,681 |

1,202 |

12.42 |

1,738 |

609 |

2,347 |

**http://zpkarwar.kar.nic.in/CensusKumtaVWP.htm

*http://zpkarwar.kar.nic.in/CensusAnkolaVWP.htm

Table 2: Village and season-wise average quantity (Kg. wet weight with shells) of bivalves harvested

| Village |

Jun-Oct |

% of total harvest |

Nov-May |

% of total harvest |

| Hiregutti |

105.00 |

0.09 |

105.00 |

0.07 |

| Aigalkurve |

300.00 |

0.25 |

300.00 |

0.20 |

| Bargigazani |

337.50 |

0.28 |

337.50 |

0.22 |

| Bargi |

412.50 |

0.34 |

412.50 |

0.27 |

| Balale |

420.00 |

0.35 |

420.00 |

0.28 |

| Lukkeri |

431.25 |

0.36 |

637.50 |

0.42 |

| Paduvani |

489.00 |

0.41 |

588.00 |

0.39 |

| Betkuli |

708.75 |

0.59 |

843.75 |

0.56 |

| Hegde |

851.25 |

0.71 |

2,062.50 |

1.37 |

| Kodkani |

1,275.00 |

1.06 |

2,175.00 |

1.45 |

| Madangeri |

1,680.00 |

1.40 |

1,680.00 |

1.12 |

| Morba |

2,497.50 |

2.08 |

3,060.00 |

2.04 |

| Toregazani |

2,551.50 |

2.13 |

6,014.25 |

4.01 |

| Kagal |

4,890.00 |

4.08 |

4,230.00 |

2.82 |

| Torke |

5,782.50 |

4.82 |

7,188.00 |

4.79 |

| Mirjan |

5,940.00 |

4.96 |

7,320.00 |

4.88 |

| Gokarn |

9,945.63 |

8.30 |

11,922.00 |

7.95 |

| Divgi |

23,565.00 |

19.66 |

30,465.00 |

20.31 |

| Aghanashini |

57,683.20 |

48.12 |

70,270.96 |

46.84 |

| Total |

119,865.58 |

|

150,031.96 |

|

Table 3: Village and season-wise average quantity of bivalves harvested (in kg. wet weight with shells) by men

| Village |

QHD: Jun-Oct |

BCD in Jun - Oct |

Total harvest (kg) - Jun-Oct |

QHD: Nov-May |

BCD in Nov - May |

Total harvest (kg) - Nov-May |

| Hiregutti |

105 |

44 |

4,620 |

105 |

154 |

16,170 |

| Bargigazani |

338 |

32 |

10,800 |

338 |

64 |

21,600 |

| Bargi |

263 |

26 |

6,825 |

263 |

96 |

25,200 |

| Aigalkurve |

165 |

13 |

2,145 |

165 |

182 |

30,030 |

| Paduvani |

225 |

100 |

22,500 |

225 |

140 |

31,500 |

| Balale |

420 |

9 |

3,780 |

420 |

108 |

45,360 |

| Betkuli |

709 |

9 |

6,379 |

844 |

85 |

71,719 |

| Hegde |

638 |

13 |

8,288 |

1,849 |

120 |

221,850 |

| Morba |

2,475 |

8 |

19,800 |

3,038 |

78 |

236,925 |

| Kodkani |

1,125 |

10 |

11,250 |

1,875 |

132 |

247,500 |

| Madangeri |

1,680 |

96 |

161,280 |

1,680 |

168 |

282,240 |

| Kagal |

4,620 |

18 |

83,160 |

3,960 |

80 |

316,800 |

| Toregazani |

2,498 |

48 |

119,880 |

5,951 |

96 |

571,320 |

| Mirjan |

3,960 |

40 |

158,400 |

4,500 |

138 |

621,000 |

| Torke |

5,760 |

45 |

259,200 |

7,110 |

102 |

725,220 |

| Gokarn |

9,430 |

33 |

311,190 |

11,378 |

78 |

887,445 |

| Divgi |

15,960 |

10 |

159,600 |

21,330 |

90 |

1,919,700 |

| Aghanashini |

56,689 |

71 |

4,024,951 |

67,278 |

117 |

7,871,580 |

| Total |

107,058 |

|

5,374,047 |

132,307 |

|

14,143,159 |

BCD – Bivalve collecting days; QHD – Quantity harvested per day

Table 4: Village and season-wise average quantity of bivalves harvested (in kg. wet weight with shells) by women

| Village |

QHD: Jun-Oct |

BCD in Jun - Oct |

Total harvest (kg) - Jun-Oct |

QHD: Nov-May |

BCD in Nov - May |

Total harvest (kg) - Nov-May |

| Morba |

23 |

34 |

765 |

23 |

119 |

2,678 |

| Toregazani |

54 |

30 |

1,620 |

63 |

96 |

6,048 |

| Torke |

23 |

51 |

1,148 |

78 |

102 |

7,956 |

| Aigalkurve |

135 |

10 |

1,350 |

135 |

133 |

17,955 |

| Bargi |

150 |

36 |

5,400 |

150 |

126 |

18,900 |

| Kagal |

270 |

7 |

1,890 |

270 |

98 |

26,460 |

| Paduvani |

264 |

10 |

2,640 |

363 |

90 |

32,670 |

| Hegde |

214 |

12 |

2,565 |

214 |

168 |

35,910 |

| Kodkani |

150 |

10 |

1,500 |

300 |

126 |

37,800 |

| Gokarn |

516 |

75 |

38,672 |

545 |

105 |

57,173 |

| Lukkeri |

431 |

10 |

4,313 |

638 |

102 |

65,025 |

| Aghanashini |

994 |

49 |

48,694 |

2,993 |

114 |

341,145 |

| Mirjan |

1,980 |

48 |

95,040 |

2,820 |

161 |

454,020 |

| Divgi |

7,605 |

11 |

83,655 |

9,135 |

120 |

1,096,200 |

| Total |

12,807 |

|

289,251 |

17,725 |

|

2,199,939 |

BCD – Bivalve collecting days; QHD – Quantity harvested per day

Table 5: Village, season and gender-wise income per year from bivalve collection

| Village |

Men |

Women |

Total (Rs.) |

| June - Oct |

Nov - May |

June - Oct |

Nov - May |

| Aghanashini |

14,247,842 |

17,979,543 |

158,992 |

704,600 |

33,090,977 |

| Divgi |

568,830 |

4,428,772 |

291,182 |

2,378,217 |

7,667,001 |

| Mirjan |

563,418 |

1,422,253 |

328,839 |

967,109 |

3,281,619 |

| Gokarn |

969,601 |

1,836,715 |

135,472 |

130,651 |

3,072,439 |

| Torke |

795,644 |

1,427,533 |

62,813 |

285,116 |

2,571,106 |

| Toregazani |

431,482 |

1,333,506 |

86,293 |

201,571 |

2,052,852 |

| Madangeri |

588,305 |

672,031 |

|

|

1,260,336 |

| Kagal |

289,145 |

719,192 |

6,867 |

62,622 |

1,077,826 |

| Kodkani |

41,044 |

589,468 |

5,036 |

79,019 |

714,567 |

| Hegde |

29,770 |

515,903 |

9,405 |

86,184 |

641,262 |

| Morba |

60,376 |

425,015 |

36,535 |

77,000 |

598,926 |

| Paduvani |

75,219 |

65,406 |

9,579 |

77,161 |

227,365 |

| Betkuli |

21,459 |

150,423 |

|

|

171,882 |

| Aigalkurve |

7,714 |

69,957 |

4,950 |

43,092 |

125,713 |

| Balale |

13,589 |

105,607 |

|

|

119,196 |

| Lukkeri |

|

|

11,397 |

89,487 |

100,884 |

| Bargi |

14,748 |

22,534 |

19,365 |

43,839 |

100,486 |

| Bargigazani |

38,767 |

50,173 |

|

|

88,940 |

| Hiregutti |

16,848 |

38,485 |

|

|

55,333 |

| Total |

18,773,801 |

31,852,516 |

1,166,725 |

5,225,668 |

57,018,710 |

Value which is in bold is the median value

Table 6: Village-wise income (Rs.) per year from shell sale

| Village |

BHH |

SHH |

No. of basket (Shells) sales / family |

Rs. / basket |

Income (Rs.) / family |

Total (Rs.) / village |

| Hiregutti |

1 |

1 |

25 |

10 |

250 |

250 |

| Aigalkurve |

5 |

3 |

28 |

10 |

280 |

840 |

| Kodkani |

29 |

20 |

11 |

11 |

121 |

2,420 |

| Balale |

10 |

10 |

28 |

11 |

303 |

3,025 |

| Paduvani |

13 |

7 |

35 |

13 |

438 |

3,063 |

| Hegde |

31 |

19 |

16 |

11 |

176 |

3,344 |

| Bargigazani |

5 |

5 |

50 |

15 |

750 |

3,750 |

| Madangeri |

20 |

20 |

40 |

10 |

400 |

8,000 |

| Mirjan |

89 |

36 |

23 |

11 |

256 |

9,207 |

| Torke |

72 |

18 |

75 |

9 |

638 |

11,475 |

| Gokarn |

98 |

33 |

41 |

12 |

488 |

16,088 |

| Toregazani |

38 |

19 |

148 |

11 |

1,623 |

30,828 |

| Kagal |

33 |

26 |

118 |

12 |

1,416 |

36,816 |

| Morba |

34 |

26 |

143 |

12 |

1,710 |

44,460 |

| Divgi |

323 |

226 |

35 |

14 |

490 |

110,740 |

| Aghanashini |

340 |

139 |

118 |

12 |

1,416 |

196,824 |

| Total |

1,141 |

609 |

|

|

10,752 |

481,129 |

BHH – Bivalve collecting households; SHH – Shell selling households

Table 7: Village-wise income (Rs.) per year from dried meat sale

| Village |

BHH |

DHH |

kg sales / family |

Rs. / kg |

Expense (Rs.) |

Income (Rs.) / family |

Total (Rs.) / village |

| Bargigazani |

5 |

5 |

2 |

200 |

|

300 |

1,500 |

| Hiregutti |

1 |

1 |

18 |

150 |

|

2,625 |

2,625 |

| Paduvani |

13 |

3 |

9 |

250 |

110 |

2,140 |

6,420 |

| Torke |

72 |

13 |

4 |

160 |

20 |

620 |

8,060 |

| Aigalkurve |

5 |

3 |

20 |

150 |

135 |

2,865 |

8,595 |

| Kagal |

33 |

13 |

6 |

175 |

200 |

894 |

11,619 |

| Morba |

34 |

17 |

8 |

166 |

88 |

1,159 |

19,709 |

| Balale |

10 |

5 |

40 |

100 |

25 |

3,975 |

19,875 |

| Madangeri |

20 |

20 |

8 |

175 |

150 |

1,163 |

23,250 |

| Divgi |

323 |

129 |

2 |

120 |

13 |

183 |

23,543 |

| Toregazani |

38 |

29 |

17 |

150 |

147 |

2,353 |

68,247 |

| Aghanashini |

340 |

170 |

8 |

127 |

175 |

834 |

141,696 |

| Total |

894 |

408 |

|

|

|

19,110 |

335,138 |

BHH – Bivalve collecting households; SHH – Shell selling households

|

|