|

Central

Pennsylvania Fold Belt; The Appalachians

|

Our imaginary airplane flight now passes over central Pennsylvania. The dominant landscape feature is the zig-zag folds that characterize the Valley and Ridge subprovince of the Appalachians. The structural expression of this mountain system varies along its length as demonstrated by several other space images.

Our odyssey proceeds west into the heart of the Appalachian fold belt that dominates the land forms of central Pennsyvania. The segment known as the Valley and Ridge has very distinctive topography: the ridges are curved, some shaped almost like an arrowhead, and have generally uniform elevations (not pointed or irregular like many western mountains). They are even today forest-covered but the valleys in between are flat to rolling and commonly developed for agriculture. This aerial oblique photo shows a typical expression of this:

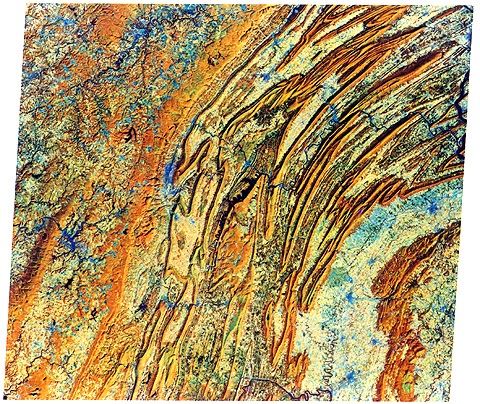

That photo is included in this unusually

colored Fall Landsat MSS composite. Most of the interior of this image depicts

the Valley and Ridge province which runs from southernmost New York state to Alabama.

The area shown includes the center of Pennsylvania.

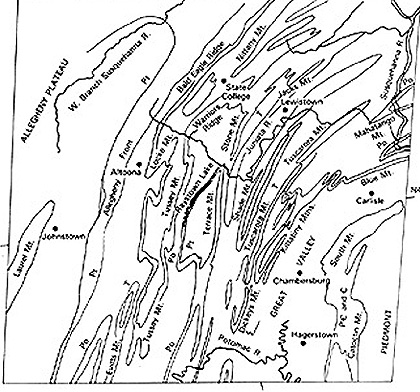

The following sketch map names the

principal mountain ridges and other features found in this scene:

Here, the sedimentary rocks that compiled

thicknesses up to 15,250 m (50,000 ft) in parts of the geosynclinal deposition

basin during the Paleozoic era, were strongly folded into anticlines (uparches)

and synclines (downbends). These rocks were also shoved westward along thrust

fault sheets. Erosion since the Appalachian Revolution has repeatedly sculpted

ridges out of harder rocks (most commonly, sandstones) and valleys out of weaker

rocks (such as shales). This erosion results in a zig-zag pattern developed from

folds that also curve sharply as they pinch out, as seen in plan or horizontal

perspective. The ridges, few of which are higher than 460 m (1,500 ft), remain

heavily forested but the valleys are mostly cleared for agriculture. Toward the

lower right corner, shales and limestones of early Paleozoic age underlay a broader

lowlands, the Great Valley of Pennsylvania (the northern extension of the Shenandoah

Valley of Virginia).

The wide isolated ridge to the southeast

is South Mountain/Catoctin Mountain, a complex of igneous-sedimentary-metamorphic

rocks, which connects with similar rocks in the Blue Ridge in Virginia. The

Appalachian Plateau occupies the western (left) part of the image and continues

for several hundred kilometers into eastern Ohio. Its rocks are also Paleozoic

sedimentary units that were not strongly folded (the compression effects die

down in this region) and are still subhorizontal. However, the rock units were

lifted en masse during the orogeny and, more recently, to elevations high enough

to foster deep local stream cutting. The stream courses here are typical of

the dendritic drainage pattern that develops on elevated terrain underlain by

rocks of similar resistance to erosion. 6-6: The town of State College is the home of the

Nittany Lions, the football team at Penn State University. It is situated in

"Happy Valley" and is overlooked by Nittany Mountain; find it. Deep in the woods

of South Mountain is a famed location where U.S. Presidents like to go; name

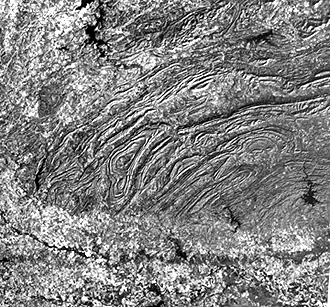

it. ANSWER Radar has produced many splendid

images of the Folded Appalachians, since the ridges stand out sharply because

of the radar shadow effect. This X-band image, acquired from an aircraft by

Intera Technologies of Ottawa, Canada, shows a swath 50 km (31 miles) wide that

is contained in the Landsat image (you can locate it in that image by the distinctive

fold pattern near the center of the radar scene). Look direction is from the

west (left). The city of Altoona, PA is the bright, stretched out speckled pattern

just above left center. The upper left corner shows the topography of the Appalachian

Plateau, another subprovince of this mountain system.

The U.S. Appalachians extend into

northern Georgia and Alabama, south of which they go underground, being buried

by sediments comprising the Coastal Plains. Actually, the general orogenic belt

that includes the Appalachian Mountains of eastern North America extends westward

across the Mississippi River through the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas/Oklahoma

before dying out in Texas. Its northern end passes through Maine into Nova Scotia

and Newfoundland and has been traced into mountain systems in the British Isles

and Norway. The Atlas Mountains of northwestern Africa also link to the Appalachians.

This once continuous belt split at the end of the Paleozoic Age, as the present

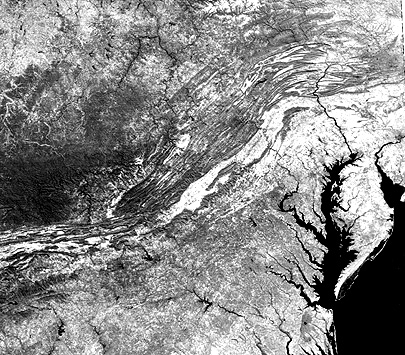

continents broke apart and their tectonic plates then drifted in several directions. We now take a momentary detour in

our flight to look at parts of the central and southern Appalachians. The first

scene shows much of the Appalachian Belt from Pennsylvania through North Carolina,

as depicted in this Day-Vis (0.5 - 1.1 Ám) image made by the Heat Capacity Mapping Radiometer

on HCMM (see Section 9-8 for a description

of this 1978 mission).

The swath width covered by the image

is 715 km (444 miles); spatial resolution is 500 m (1,640 ft). To get your bearings

at this scale, locate Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA on an atlas. This overview

scene is shows the entire central part of the Appalachian Mountain system in a

single view. The fold belt of the Valley and Ridge Province is distinctive. At

the northern end, in Pennsylvania, the zig-zag pattern described above is determined

by the closed or pitching anticlines and synclines. This type of folding largely

disappears to the south, being replaced by subparallel ridges separated by valleys.

Note the sharp bend or kink in the belt near Roanoke, VA. This feature is, in

part, fault-controlled. We can see the Blue Ridge because it lies to the east

of the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia that continues as the Great Valley through

Pennsylvania (both in light tones).

The Piedmont to the southeast is

not particularly obvious in this image. Its terrain does not express well because

of generally low relief. Its boundary with the Coastal Plains is the Fall Line,

so-called because waterfalls form along some streams as they descend from harder

Piedmont rocks to softer rocks toward the coast. This boundary is also diffuse,

but generally its tone is darker than that of the Coastal Plains (more farming

and less trees). The Cumberland Plateau, west of the belt, is much darker because

of heavy forestation. As that province grades into the Allegheny Plateau, the

dissected morphology remains, but forest cover diminishes. 6-7: Where is the Delmarva peninsula; locate the

Shenandoah Valley of Civil War battle fame. Where is Pittsburgh. What state

occupies the upper left 1/6th of the image? Name all the states that are entirely

or partly present in the image. ANSWER The second image is a Landsat subscene,

covering about 100 km (62 miles) left-right, that contains parts of Tennessee,

Virginia, and North Carolina. Kingsport, TN is the fuzzy blue patch in the center

about 1/3 down. Douglas Lake on the French Broad River lies at the lower left

corner. A section of the Great Smoky Mountains,

north of Ashville, occupies the lower right corner of the image. This is an

assemblage of relatively homogeneous crystalline rocks that includes the Blue

Ridge on their eastern side. Running diagonally through the image center is

part of the Tennessee Valley, which is rolling hills underlain by more easily

eroded limestones that tie into the Shenandoah Valley to the north. The Valley

and Ridge is represented here by continuous folds of steeply dipping rocks that

are also involved in the Pine Mountain thrust. The upper left is the beginning

of the Cumberland Plateau, a southern extension of the Allegheny Plateau of

Pennsylvania. Note the similarities and differences of this subscene and the

earlier one. Here the South Mountain counterparts are much wider. What is normally thought of as the

southern tip of the Appalachians occurs where the mountains seem to end abruptly

in northern Alabama. Actually, they continue westward across the Mississippi

River embayment and reappear in northern Arkansas as the Ouachita Mountains,

as seen below in a Landsat image. In fact, segments of the continuation of the

Paleozoic fold belt that formed these mountains surface again in Oklahoma and

probably extend (buried) only to reappear in northern Mexico.

For the writer (NMS), this image remains an especially fond memory. Prior to launch of ERTS (Landsat-1), my then skeptical outlook born of unfamiliarity with the potential for space imagery to show much of significance to Geology had led him earlier to comment publicly that I didn't expect too much of usefulness from this new satellite. The first day that about 100 management persons and the scientists were gathered at the ERTS Data Receiving Center (in Building 22) the initial RBV image was a disappointing polaroid of the Dallas-Fort Worth area (see page 4-5) that seemed to reenforce this view. Then, an hour later the first can containing a continuous strip of 70mm black and white transparencies representing the first MSS images was brought into the room. Because none of the guests knew how to use the image display unit (but I did, as did the processing staff), I was delegated to load it for viewing. As I scrolled downward from imagery taken over Minnesota down to southern Missouri, all views were completely cloud-covered. Disappointing! Then, hallelujah, the next image was completely free of clouds. It was stunning! Much beyond my expectations. I was so thrilled, yet humbled, I turned to Len Jaffe - the NASA Associate Administrator for Earth Sciences - and uttered this (immortal?) line: "I am so wrong about my predictions that I will not eat Crow but will consume Raven instead.". Thus did I convert to ERTS/Landsat and to remote sensing in general.