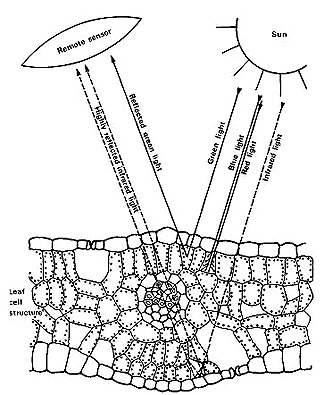

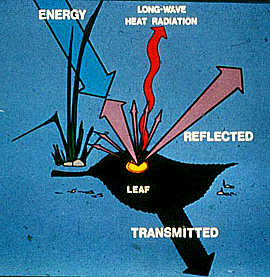

Now, consider this diagram

which traces the influence of green leafy material on incoming and reflected radiation.

Absorption centered at

about 0.65 Ám (visible red) by chlorophyll pigment in green-leaf chloroplasts

that reside in the outer or Palisade leaf, and to a similar extent in the blue,

removes these colors from white light, leaving the predominant but diminished

reflectance for visible wavelengths concentrated in the green. Thus, most vegetation

has a green-leafy color. There is also strong reflectance between 0.7 and 1.0

Ám (near IR) in the spongy mesophyll cells located in the interior or back of

a leaf, within which light reflects mainly at cell wall/air space interfaces,

much of which emerges as strong reflection rays. The intensity of this reflectance

is commonly greater (higher percentage) than from most inorganic materials,

so vegetation appears bright in the near-IR wavelengths. These properties of

vegetation account for their tonal signatures on multispectral images: darker

tones in the blue and, especially red, bands, somewhat lighter in the green

band, and notably light in the near-IR bands (maximum in Landsat's Multispectral

Scanner Bands 6 and 7 and Thematic Mapper Band 4 and SPOT's Band 3).

Identifying vegetation in

remote-sensing images depends on several plant characteristics. For instance,

in general, deciduous leaves tend to be more reflective than evergreen needles.

Thus, in infrared color composites, the red colors associated with those bands

in the 0.7 - 1.1 Ám interval are normally richer in hue and brighter from tree

leaves than from pine needles.

These spectral variations

facilitate fairly precise detecting, identifying and monitoring of vegetation

on land surfaces and, in some instances, within the oceans and other water bodies.

Thus, we can continually assess changes in forests, grasslands and range, shrublands,

crops and orchards, and marine plankton, often at quantitative levels. Because

vegetation is the dominant component in most ecosystems, we can use remote sensing

from air and space to routinely gather valuable information for characterizing

and managing of these organic systems.

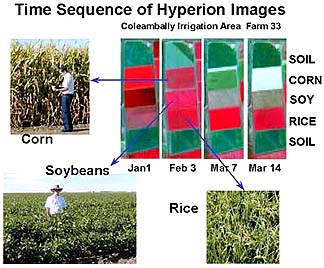

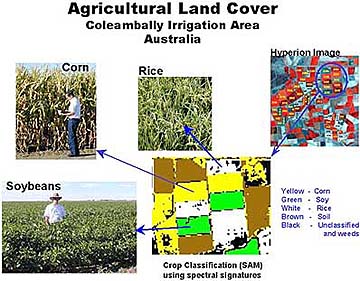

One of the most successful

applications of multispectral space imagery is monitoring the state of the world's

agricultural production. This application includes identifying and differentiating

most of the major crop types: wheat, barley, millet, oats, corn, soybeans, rice,

and others.

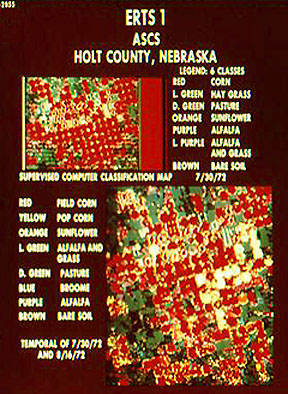

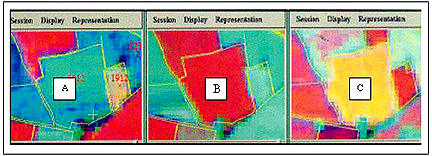

This capability was convincingly

demonstrated by an early ERTS-1 classification of several crop types being grown

in Holt County, Nebraska. This pair of image subsets, obtained just weeks after

launch, indicates what crops were successfully differentiated; the lower image

shows the improvement in distinguishing these types by using data from two different

dates of image acquisition:

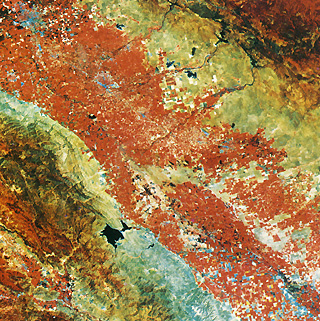

Perhaps this is a good

point in the discussion to introduce the appearance of large area croplands

as they appear in Landsat. We will illustrate with imagery that cover the two

major crop growing areas of the United States.

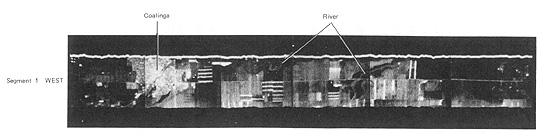

The first is part of the Great

or Central Valley of California, specifically the San Joaquin Valley. Agricultural

here is primarily associated with such cash crops as barley, alfalfa, sugar beets,

beans, tomatoes, cotton, grapes, and peach and walnut trees. In July of 1972 most

of these fields are nearing full growth. Irrigation from the Sierra Nevada, whose

foothills are in the upper right compensates for the sparsity or rain in summer

months. The eastern Coast Ranges appear at the lower left. The yellow-brown and

blue areas flanking the Valley crops are grasslands and chapparal best suited

for cattle grazing. The blue areas within the croplands (near the top) are the

cities of Stockton and Modesto.

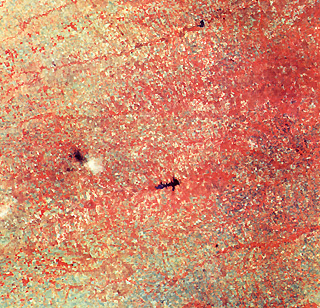

The second Landsat image

is in the Wheat Belt of the Great Plains. The image below is of western Kansas

in late August. Most of the scene consists of small farms, many of section size

(1 square mile). The principal crop is winter wheat which is normally harvested

by June. Spring wheat is then planted, along with sorghum, barley, and alfalfa.

This scene is transitional, with nearly all of the right side being heavily

planted, but the left side (the High Plains, at higher elevations) contains

some unplanted farms and barren land, some used for grazing.

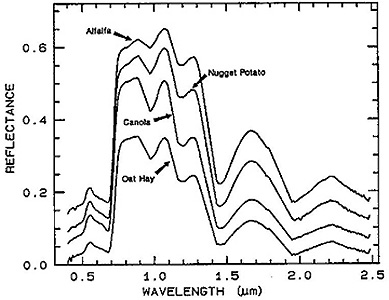

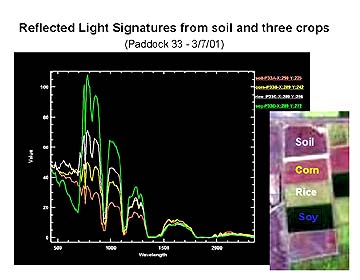

Many factors combine to cause

small to large differences in spectral signatures for the varieties of crops cultivated

by man. Generally, we must determine the signature for each crop in a region from

representative samples at specific times. However, some crop types have quite

similar spectral responses at equivalent growth stages. The differences between

crop (plant) types can be fairly large in the Near-Infrared, as shown in these

spectral curves (in which other variables such as soil type, ground moisture,

etc. are in effect held constant).

3-1:

Drawing on your experience and common sense, make (or

think) a list of the factors that will affect the spectral signatures of field

crops. ANSWER

Through remote sensing it

is possible to quantify on a global scale the total acreage dedicated to these

and other crops at any time. Of greater import, is accurately (best case 90%)

estimating the expected yields (production in bushels or other units) of each

crop, locally, regionally or globally. We do this by first computing the areas

dedicated to each crop, and then incorporating reliable yield assessments per

unit area, which agronomists can measure at representative ground-truth sites

(or in the U.S., county farm agents obtain routinely from the farmers themselves).

Reliability is enhanced by using the repeat coverage of the croplands afforded

by the cyclical satellite orbits assuming, of course, cloud cover is sparse enough

to foster several good looks during the growing season. Usually, the yield estimates

obtained from satellite data are more comprehensive and earlier (often by weeks)

than determined conventionally as harvesting approaches. Information about soil

moisture content, often critical to good production, can be qualitatively (and

under favorable conditions, quantitatively) appraised with certain satellite observations.

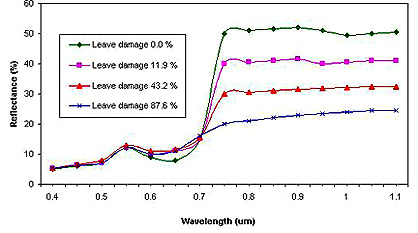

Under suitable circumstances,

it is feasible to detect crop stress generally from moisture deficiency or disease

and pests, and sometimes suggest treatment before the farmers become aware of

problems. Stress is indicated by progressive decrease in Near-IR reflectance,

as evidenced in this set of field spectral measurements of leaves taken from soybean

plants as these underwent increasing stress that causes loss of water and breakdown

of cell walls.

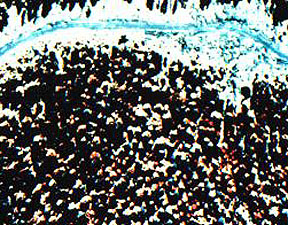

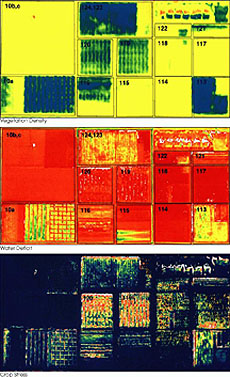

Differences in vegetation

vigor, resulting from variable stress, are especially evident when Near Infrared

imagery or data are used. In this aerial photo made with Color IR film shows

healthy vegetation in red, and "sick" (stressed) vegetation in blue to yellow-white:

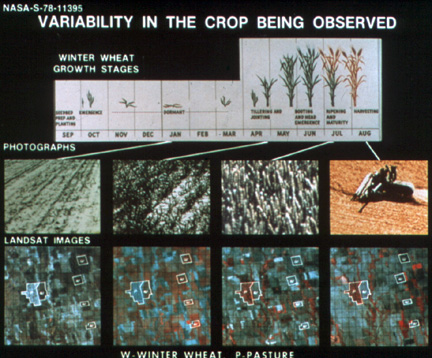

For identifying crops, two

important parameters we use are the size and shape of the crop type ( e.g. soybeans

have spread out leaf clumps; corn has tall stalks with long, narrow leaves and

thin, tassle-topped stems; and wheat [in the cereal grass family] has long thin

central stems with a few small, bent leaves on short branches, all topped by a

head containing the kernels from which flour is made). Other considerations are

the surface area of individual leaves, the plant height and amount of shadow it

casts, and the spacing or other planting geometries of row crops (the normal arrangement

of legumes, feed crops, and fruit orchards). The stage of growth (degree of crop

maturity) is also a factor. For example during its development wheat, passes through

several distinct steps such as, developing its kernel-bearing head, and changing

from shades of green to golden-brown (see below).

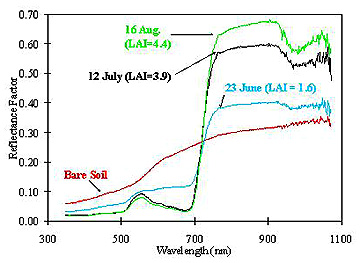

Another related parameter

is Leaf Area Index (LAI), defined as the ratio of one-half the total area of leaves

(the other half is the underside) in vegetation to the total surface area containing

that vegetation. If all the leaves were removed from a tree canopy and laid on

the ground, their combined areas relative to the ground area projected beneath

the canopy would be some number greater than 1 but usually less than 10. As a

tree, for example, fully leaves, it will produce some LAI value that is dependent

on leaf size and shape, the number of limbs, and other factors. The LAI is related

to the the total biomass (amount of vegetative matter [live and dead] per unit

area, usually measured in units of tons or kilograms per hectare [2.47 acres])

in the plant and to various measures of Vegetation Index (see below). Estimates

of biomass can be carried out with variable reliability using remote sensing inputs,

provided there is good supporting field data and the quantitative (mathematical)

models are efficient. Both LAI and NDVI (page 3-4) are used in the

calculations.

In principal, actual LAI

must be determined on site directly by stripping off all leaves, but in practice

it can be estimated by statistical sampling or by measuring some property such

as reflectance. Thus, remote sensing can determine an LAI estimate if the reflectances

are matched with appropriate field or ground truth. For remotely sensed crops,

LAI is influenced by the amount of reflecting soil between plant (thus looking

straight down will see both corn and soil but at maturity a cornfield seems

closely spaced when viewed from the side). For the spectral signatures shown

below, the Near IR reflectances will increase with LAI.

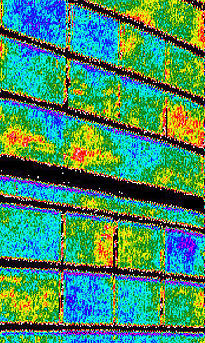

This change in appearance

and extent of surface area coverage over time is the hallmark of vegetation as

compared with most other categories of ground features (especially those not weather-related).

Crops in particular show strong changes in the course of a growing season, as

illustrated here for these three stages - bare soil in field; full growth; fall

senescence:

3-2:

How would non-growing or dead vegetation (such as crops

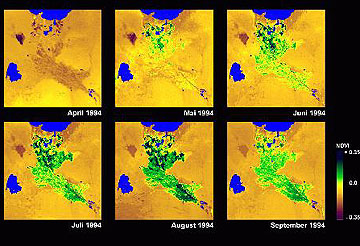

in senescence) be detected by Landsat? ANSWER The study of vegetation

dynamics in terms of climatically-driven changes that take place over a growing

season is called phenology. A good example of how repetitive satellite

observations can provide updated information on the phenological history of

natural vegetation and crops during a single cycle of Spring-Summer growth is

this sequence of AVHRR images of the Amu-Dar'ja Delta just south of the Aral

Sea in Ujbekistan (south-central Asia).The amount of vegetation present in the

delta (a major farming district for this region) is expressed as the NDVI, an

index defined on page

3-4. The Aral Sea - a large inland lake - is now rapidly drying up (see

page page 14-15).

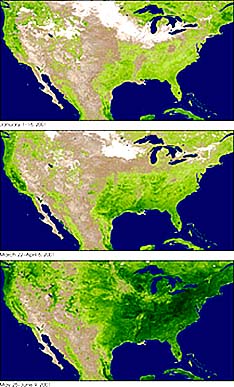

More generally, seasonal

change appears each year with the "greening" that comes with the advent of Spring

into Summer as both trees and grasses commence their annual growth. The leafing

of trees in particular results in whole regions becoming dominated by active

vegetation that is evident when rendered in a multispectral image in green tones.

The MODIS sensor on Terra has several vegetation-sensitive bands used to calculate

a variation of the NDVI called the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI). This trio

of images (dates in the caption) shows the spread of growing natural vegetation

across the U.S.

To emphasize the variability

of the spectral response of crops over time, we show these phenological stages

for wheat in this sequential illustration: