|

Recognition

of Faults and Joints

|

Another regional scale feature usually easy to recognize in suitable space imagery is that of faulting. A fault is a fracture in the Earth’s crust along which there has been some relative movement of rock on one side against the other side. This appears as some form of displacement or offset of once contiguous units. Joints are fractures that do not involve differential movement; they are usually too small in size to be directly recognizable from space but their effect on topography may reveal their presence. Two examples are shown.

Faults are fractures along which there is relative sliding movement of the blocks in opposite directions on either side. We recognize them by various criteria:

1) Layers of different types and ages of rock units sit side-by-side

2) Abrupt topographic discontinuities of landforms

3) Depressions along the fault trace (broken rock is more easily eroded)

4) Scarps or cliffs

5) Sudden shifts of drainage courses.

6) Abrupt changes in vegetation patterns

Joints can be conspicuous under certains conditions, where they are long, continuous, wide-spaced and enlarged by erosion. This is well shown by the joint system cutting a basalt flow in Zambia over which flows the Zambesi River (Victoria Falls).

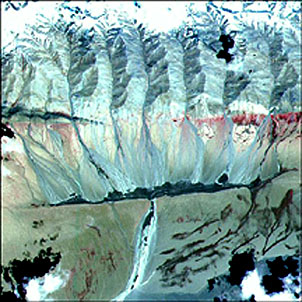

The scene below of the Kuruk

Tagh fault in part of the Tian Shan mountains of westernmost China shows a sharp

fault trace running east-west through the Kuruk Tagh hills. It's composed of folded

sedimentary strata, metamorphic rocks, and igneous intrusions. The block of crust

on the north side has shifted sub-horizontally to the west (left) at least 60

km relative to the block containing the corresponding segment of mountains to

the south. This type is a left-lateral wrench fault (also called a strike-slip

fault). It's a type similar to the San Andreas fault, which is a right-lateral

fault, with the Pacific plate moving northward against the North American plate

the famed earthquake-maker running from the Gulf of California through the California

Coastal Ranges north of San Francisco (see the Los Angeles mosaic further down

this page and the L.A. image in Section 4 and the San Francisco

images in Section 6).

Comparable to the San Andreas

fault is the Dead Sea Fault that runs from just below the mountains of east

Lebanon southward through the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea (both actually

lakes), thence into the Gulf of Aqaba. This fault marks one of the three arms

of the Afar Triple Junction (see page 17-3). Here it is shown

in a mosaic made from two Landsat images.

The fault is recognized

in part by topographic discontinuities (mountains in Jordan not fitting with

those on the western side) and because the Jordan River and the two lakes follow

zones of weakness that are erodes so that they are lower than their surroundings

(land adjacent to the Dead Sea has the lowest elevation on land anywhere on

Earth; in places below - 300 feet). The Kuruk Tagh fault in

east Asia, another strike-slip fault, is easy to identify because of topographic

offset (as well as equivalent parts of the strata and metamorphosed rock units),

fault scarps, and displaced drainage. This and similar major wrench faults in

south-central Asia represent crustal adjustments to the stresses induced by

the collision of India against Asia (see mosaic in Section 7).

2-13:

Can you find a second major fault in this scene?

ANSWER Another major fault zone

in western China near Tibet is the Kunlun strike-slip (left lateral) system.

In the ASTER image below, the fault has split into two parallel segments. The

lower one has produced a topographic barrier against which water (black) has

been impounded to form a long, narrow lake. Above a series of alluvial fans

is the upper segment from within which water has emerged to flow downslope and

to enable vegetation (red) to grow.

One of the best known and

studied fault zones in the world makes up the East African Rift complex that runs

from Ethiopia south through Kenya (see also Section 3, page 3-2. Here, a part

of Africa is splitting off from the continental nucleus to its west, as an incipient

mid-ocean ridge is forming by rifting centered on the Afar in Ethiopia. This image,

extracted from a photo taken by astronauts using the Large Format Camera (LFC),

shows a number of step faults (of the 'normal' type) which cuts into basaltic

flows making up rift valleys:/p>

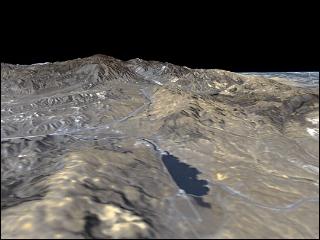

A region in the U.S. famed

for its propensity to earthquakes is much of California from the Mexican border

to about 100 km (62 miles) north of San Francisco. North of the Los Angeles

Basin is a series of mountain ranges trending towards an east-west orientation.

These collectively are known as the Transverse Ranges, and include the San Gabriel

and Santa Monica Mountains north of Los Angeles. They are criss-crossed by faults

that have a strong effect on their topography. Although most of these are wrench

or strike-slip types of faulting (dominantly horizontal slip motion), they are

capable of influencing the fronts of ranges in a manner similar to the normal-type

of fault. Here is a perspective view of the Transverse Ranges made by combining

Landsat imagery with topographic data acquired by JPL's SRTM mission (radar

altimetry). Fault lines have been drawn on the resulting image, which also depicts

the Los Angeles Basin (left) and the Mojave Desert (right).

No doubt the most famous

fault in North America is the San Andreas, a major strike-slip type, that runs

from the Gulf of California northward more or less parallel to the California

coastline until it finally passes out to sea as a transverse fault in Bodega

Bay north of San Francisco. In the ranges north of Los Angeles the San Andreas

marks a prominent straight boundary with the southern Mojave Desert. This is

evident in this image which is actually a beautifully produced aerial photomosaic

that includes the Los Angeles Basin, with its many cities, to the south.

An aerial oblique photo

shows the fault in an area of the Coast Ranges in the Carizzo Plains northeast

of Morro Bay. The fault here has a small scarp or cliff to the west of which

the land is slightly higher and dissected.

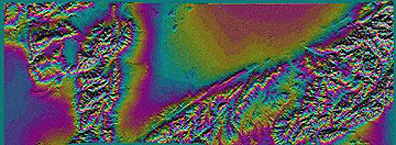

Segments of the San Andreas

have been imaged by Landsat, SPOT, and radar systems many times. Here we show

the latest example: an unusual portrayal of its appearance in a C-band image

specially processed to give landform information, with elevation variation shown

as a series of color bands. The imaging instrument is the Shuttle Radar Topography

Mission (SRTM) that is discussed more fully in Section 11. Compare

this image with the aerial photomosaic shown above: the straight boundary along

the northern Tranverse Ranges in both images stands out. The image orientation

is shifted somewhat from the mosaic, with the Mojave salient apex now pointing

down at the left.

As is described in Section

11 and elsewhere, imagery coupled with elevation data (in STRM's case, from

its own stereo-like capability) can be recast in the perspective mode as though

it is being viewed much like an aerial oblique photo. Here is an STRM construction

of the topography west of Palmdale, Calif. (an earthquake-active area) in which

a somewhat straight valley (holding the lake) roughly coincides with the San

Andreas fault.

Wrench faults have nearly

vertical fault planes (contact surfaces between blocks). A second fault type

is the thrust fault, in which the fault plane is at low angles relative to Earth's

surface and the usual direction of movement carries the upper (near-surface)

block over the lower block, causing rocks of different ages to be juxtaposed.

Thus, a shallow, tabular slice of crust slides (thrusts) over the fault plane

and on top of the surface ahead of it. Several such thrust slices (sheets) may

stack one on top of the other in a staggered pattern, leading to a sequence

of thrust block bands that outcrop in mountainous terrains. If each block consists

of rock types that are different in composition and erosive response, these

will appear at the surface as intervals of rock with contrasting topography.

This topography is superbly displayed in the scene below of the Pindus Mountains

of western Greece and Albania.

We can differentiate five tectonic zones, named in this generalized map, by sight because of distinct topographic variations and tonal differences related to contrasting rock types. The direction of tectonic transport is from east to west (right to left) causing the sheets to partially overlap below the surface, but each front edge occupies a different geographic position relative to the one it overrode and the one overriding it. This zone of thrust belts is part of the Balkan Alpine system, an offshoot of the European Alps that runs sub-parallel to the Apennine Mountains of Italy (see Alps mosaic in Section 7). As part of the tectonic adjustments caused by the African Plate shoving northward against the European Plate, a small tectonic plate underlying the Tyrrhenian Sea (off Sardinia) is squeezed against the Adriatic plate. The Adriatic plate then pushes it eastward against the Aegian plate, underthrusting it and causing the thrust slicing shown here.

2-14: Which two tectonic zones are hardest to recognize and separate in the above image? ANSWER