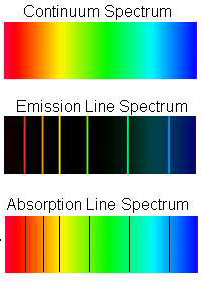

As applied to star analysis, four kinds of spectral data are relevant: 1) Continuous spectra; 2) Emission Line spectra; 3) Absorption Line spectra; and 4) Blackbody radiation spectra. The first three are illustrated here:

A Continuum Spectrum,

particularly as it applies to the UV, Visible, and Near IR segments of the ElectroMagnetic

Spectrum, is that produced by white light, i.e., all wavelengths (all colors in

the Visible) in this region are present in essentially equal proportions. An Emission

Line Spectrum results when photons of narrow, specific wavelengths are emitted

during excitation of the elements present in an emitting body; each (colored)

line is diagnostic (identifies) some particular element. An Absorption Line

Spectrum occurs when the emitted radiation from a hot body passes through

cooler gases containing the same elements as those responsible for the emitted

photons which interact (by absorption processes) and are removed from the continuum

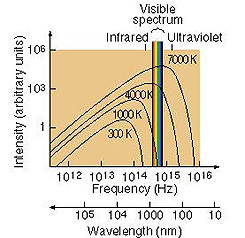

(as shown by black lines). A Blackbody Spectrum, discussed in detail on page 9-1 and 9-2, is a continuum

spectrum that is associated with the thermal state of an emitting body considered

to be a perfect radiator, especially one heated to incandescence, in which

its spectral curve peaks at some wavelength which varies systematically with temperature.

This figure should remind you of the information presented on page 9-2 dealing

with Wien's Displacement Law.

Now, in more detail: Each

element has a series of spectral lines that are diagnostic, being found in fixed

locations in a spread of the spectrum as determined by the wavelengths of emitted

radiation resulting from excitation of electrons into higher energy levels (recall

the formula: ΔE = hν). Emission lines relate to light (including UV

and IR) radiation passing unimpeded from the source. But, starlight normally

must pass through the star's atmosphere; if the outer gases contain the same

elements as those from its surface, the emitted radiation will be absorbed at

the characteristic wavelengths, giving rised to absorption spectra. The image

below is the spectrum for our Sun, with the dark absorption (Frauenhofer) lines

correlating mostly with hydrogen and helium:

Since hydrogen is by far

the most common element in the Universe, comments on its spectra are in order;

the principles involved in the generation of hydrogen's spectral lines apply

to all other elements. Radiation from excited hydrogen is detectable over most

of the EM spectral range, but important and diagnostic radiation at specific

wavelengths used by astronomers extend from the Ultraviolet through much of

the Infrared Range. Emitted radiation results when the single electron in the

neutral hydrogen atom is excited by various forms of energy (e.g., heat, electrical

current, particle bombardment) such that the electron is displaced from its

ground state to one or more of the various energy levels associated with the

possible orbital levels surrounding the nucleus. These are energy levels that

are discrete (specific values) in terms of the quantum states possible when

excitation has occurred. These levels are, by convention, represented by the

letter "N" and are expressed as integers from 1 through 2, 3, 4, 5,6, .....

infinity. In the ground state, the electron resides in level 1 (or shell, as

is often depicted in the Bohr atom model). When excitation energy is provided,

the electron can "jump" to higher (quantized) levels, as, for example from N

= 1 to N = 3. That energy is calculated by the familiar Planck equation: ΔE

= hν, where the ΔE is the energy required to move to a specific

level, say from 1 to 3, shown as E3 - E1, h is the Planck

constant, and ν is the frequency (its reciprocal is the wavelength &lamda;.

In the higher energy states (multiples of N greater than 1), the electron may

remain for a time in a metastable mode but for most of the transitions the electron

almost instantly returns to a lower energy state (either to the ground state

N = 1 or to one of the lower levels of N than the level first reached by the

electron. When the return occurs, the excitation energy is given off as photons

whose specific frequency (or wavelength equivalent) is determined by δE.

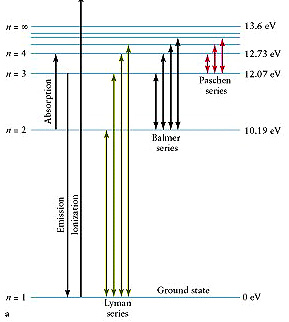

Examine this diagram:

For the Lyman series (of

transitions expressed as spectral lines of very precise wavelengths), the electrons

will move to different N levels and then revert to the N = 1 state. For the

Balmer series, the reverted level is N = 2; the Paschen series, N = 3. To illustrate

with specific values, consider the Balmer series, in which the four principal

lines, designated as Hα, Hβ, Hγ,

and Hδ, require (in the same sequence) energies (hν)of

3.02 x 10-19 , 4.07 x 10-19, 4.57 x 10-19,

and 4.84 x 10-19 Joules (J), and give off photons whose wavelengths

(state here in nanometers [µm x 1000) are 656.3, 486.1, 434.0, and 410.2 nm

respectively. The Balmer wavelengths are all in the Visible region of the spectrum.

The Lyman series occurs in the Ultraviolet and the Paschen series in the near

Infrared segments of the EM spectrum. There are other series (not named) elsewhere

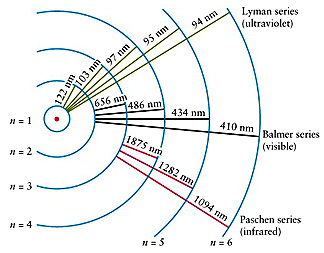

in the EM spectrum. Now, look at this next diagram - a variant of the one above

but with added information:

All of these lines are

found in solar spectra. A spectral curve (the spectrum as plotted on a strip

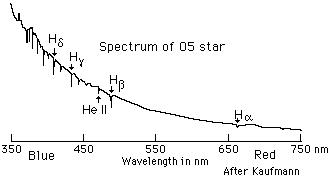

chart recorder) from an O-type (very hot) star produces absorption spikes for

the Balmer series in the Visible; it looks like this:

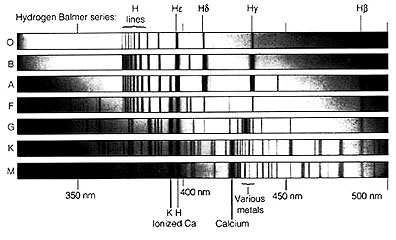

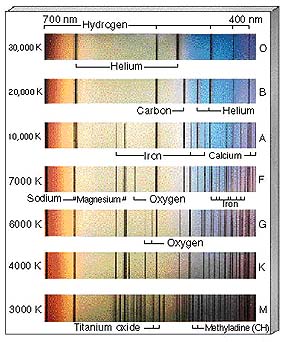

As was first treated, on

page 20-5, letters in the sequence O-B-A-F-G-K-M refer to spectral classes of

stars; the sequence is also an observed temperature indicator with each letter

denoting a range of temperatures, with O hottest (greater than 10000°K) and

M coolest (less than 3000°K), Typical spectra for the different classes of stars

on the Main Sequence will include lines for hydrogen, helium, and other elements,

shown as follows:

The following are principal

spectral lines within the Visible spectrum representing the different stellar

classes, with surface temperatures plotted on the ordinate:

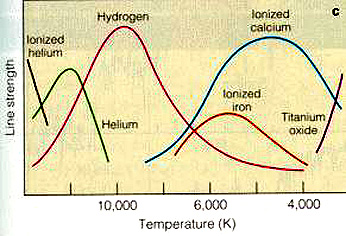

This next diagram helps

to categorize the spectral classes O through M, in which for each class a range

of spectral lines of certain individual or several elements are diagnostic and

may predominate. Thus an A star shows strong hydrogen lines with some neutral

helium and ionized metals contributing their lines whereas a K star spectrum

is predominantly that of calcium and excited neutral metals.

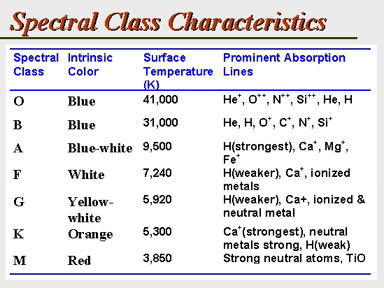

This can be restated in

the following chart that names the star class, its intrinsic surface color,

a characteristic surface temperature, and the principal diagnostic spectral

lines.

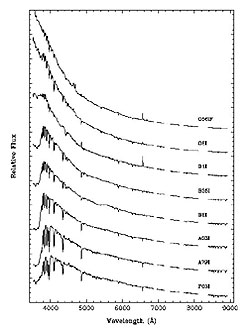

The stars off the Main

Sequence will, of course, show different spectral patterns depending on their

compositions. Below are two sets of spectral curves, with individual lines noted

as downward spikes in part of a Blackbody spectrum (see page

9-2) in the spectral range from 4000-9000 nm (0.4-0.9 µm) range. The left

set covers spectra from Blue Giants; the right from Red Giants. The shift in

peaks is a function of temperature. The left group is dominated by hydrogen

lines; in the right group some lines include calcium.

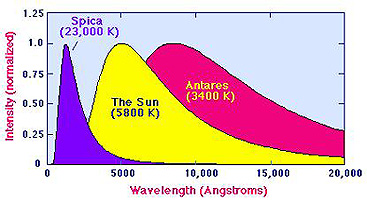

These plots suggest that

the shape of the overall Blackbody spectrum will vary as a function of temperature.

This is apparent in these generalized Blackbody spectral curves for a very hot

star (Spica), the Sun, and the cool star Antares:

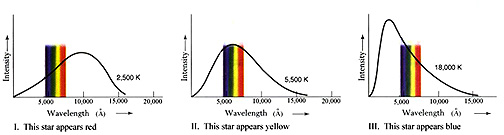

The general Blackbody curve

as it shifts with temperature also aids in showing how individual stars display

the colors astronomers assign to them. Consider this illustration:

The left curve, for a cool

star, shows that the part of the highest part on the curve intersected by the

color spread in the Visible spectrum is associated with red, hence such stars

are defined colorwise by Red. In the middle curve, the high point on the curve

is straddled by yellow; a Sunlike star then is Yellow (or Orange). The right

curve, for a hot star, has the visible blue at a higher intensity than green

or red and hence defines a Blue star (actually, as it appears, such a star is

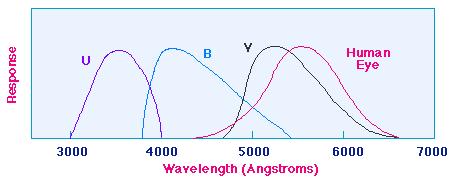

a bright bluish-white). This suggests that color

can be used in the Letter classification. Astronomers have developed a Color

Index system of relating stars to their surface temperatures. A given star is

observed through a telescope at three different wavelength ranges, one (U) centering

in part of the Ultraviolet, a second (B) in the Blue, and a third (V) in the

longer wavelength part of the Visible. The starlight passes through three filters,

as shown:

The intensity of light

received through each filter can either be expressed in flux terminology or,

more commonly, converted into an apparent magnitude value "m" appropriate to

the spectral range (e.g., mB). In turn, this magnitude must then

be converted an absolute magnitude M and then corrected for atmospheric effect

to produce what is termed a bolometric magnitude Mbol. This is necessary

so that all stars are compared in brightness at the same fixed distance. A Color

Index value in the UBV system is then calculated as B - V (and/or U - B), by

mathematically subtracting the bolometric magnitudes, as for instance, mB

- MV

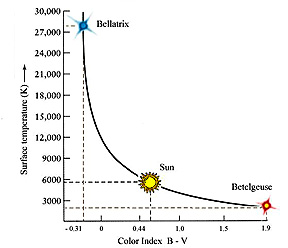

The Index can have positive

or negative values. Hotter stars have C.I.'s that are negative or slightly positive;

as magnitudes decrease with lower temperatures the Index becomes more positive.

The Sun's B - V Color Index is +0.62. In the third illustration above the star

Spica has a B - V of -0.22 and Betelgeuse a value of +1.85. A hotter star than

the Sun would have a smaller +C.I. or, with increasing temperature, values that

become negative.

Now, with this background,

let us turn our attention to how elements of atomic number above 4 have been produced

by stellar processes. In the first half billion or so years after the Big Bang,

the elemental chemistry of the Universe was quite simple. Hydrogen and helium

dominated, with very small amounts of several slightly heavier elements produced

during the early days. As galaxies began to organize from clots of slightly denser

hydrogen, the first stars formed. At that time many (most) were very massive O

and B types. These have very short lifetimes, sometimes burning their fuel in

a few million years. Their fate is to explode as supernovae, as described on page

20-6. Even smaller stars that work through the Red Giant stage have, or will,

eventually cast off a considerable amount of their elemental constituents enroute

to becoming White Dwarfs.

Stars, particularly the massive

ones mentioned above, are the furnaces in which the elements beyond H, He, and

some Li are created (stellar nucleosynthesis) by successive steps in nuclear

fusion in which more and more protons and neutrons are joined into stable to unstable

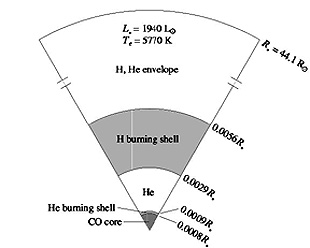

nuclei. The development of shells of elements with mass numbers greater than 2

is shown for two common cases: 1) a star of overall mass and size similar to the

Sun, and 2) A star with about 100 solar masses (not scaled; the stars are not

the same size).

Stars with solar masses between

1 and 10 (those that follow the asymptotic giant branch [AGB] described on page 20-5) tend to burn their

helium into carbon and some oxygen but do not form elements of higher atomic numbers.

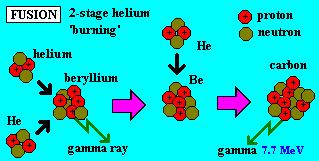

Much of the burning involves fusion of three helium atoms according to this sequence:

The red giant that results

shows the distribution of elements after fusion has produced these element shells;

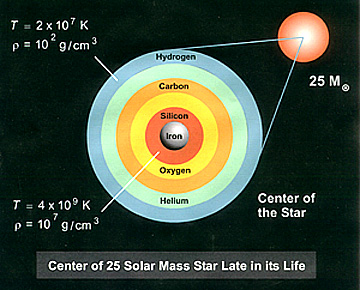

A typical, but somewhat generalized

sequence of nucleosynthesis of elements of atomic number higher than oxygen (>8)

is depicted in the figure below for a star composed initially of 25 solar masses

(MO) of hydrogen, but now is approaching (there is some hydrogen left)

its final stage of evolution (before exploding as a supernova_ in which the star

consists of a sequence of elements formed progressively with depth as it heated

up and contracted. Stars with greater than 10 solar masses will proceed to the

iron core stage; a Sun-sized star reaches only the carbon core stage.

As a massive hydrogen-rich

star contracts and experiences greater pressures, helium is the first nuclear

product within its core region. The energy released from fusion, along with continuing

densification, yields higher temperatures (1-2 x 108 K) that transmute

this innermost helium into carbon (by fusion of three helium nuclei) while producing

new helium at the next outer shell, but with hydrogen still dominant. This so-called

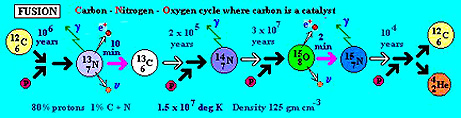

CNO (Carbon-Nitrogen-Oxygen) burning cycle is illustrated here:

Once carbon is formed in abundance,

this helium is generated as an end product of the CNO cycle. In this, some C12

reacts with protons to generate, in successive steps, N13, N14,

N15 and then O15. After this last step, that unstable oxygen

isotope can fuse with a proton and then decay by fission, thereby releasing an

alpha particle (He4, stripped of its electrons) causing the reversion

to C12.

Ever greater contraction,

with concomitant temperatures reaching > 5 x 108 K for elements

like sodium and magnesium, 1 x 109 K for oxygen, and approaching

3 x 109 K for nickel, cobalt, and iron, can progressively generate

the elements listed in the figure up to iron (plus others of lesser atomic numbers)

in amounts proportional to the comparative solar masses indicated. Thus, a star

massive enough to ultimately achieve an iron core also contains elements of

lower atomic numbers in its outer shells, broadly distributed in the relative

positions shown in the figure, reflecting response to the fuel to outwardly

decreasing densities and temperatures. Iron (atomic number Z [no. of protons]=

26; mass number A [number of protons + neutrons] = 56) is the heaviest element

producible directly by stellar fusion. In fusion, nuclear binding energies for

the new nuclides increase gradually up to iron but the mass of a fused nuclide

is less than the sum of the fusing constituents. The missing mass is converted

to energetic particles (E = mc2), given off as gamma rays, neutrinos,

positrons, and others; thus the fusion process is always an energy-releasing

one.

After stars which have

become enriched in the elements between C and Fe through fusion undergo destruction

to White Dwarfs, these dwarfs will be composed largely of the highest atomic

number element reached as the star enters the Giant phase. Many of the White

Dwarfs around 4-6 times as massive as the Sun will consist primarily of carbon.

Neutron stars, the end product of more massive star explosions, do not have

any specific element since protons and electrons have been forced together to

make neutrons, thus destroying the elemental identity reached by these stars

prior to this extreme transition.

Elements with A greater than

Fe have decreasing binding energy and to form require energy input from non-fusion

processes (principally neutron capture). Because those stars capable of synthesizing

elements up to Fe have masses greater than 10 solar masses, these stars at their

end stage of fusion will rapidly (over spans of hundreds of years) collapse and

explode (fly apart) as supernovae. This gives rise to intense neutron fluxes that

manufacture various elements including those with A > 56 , most of which become

rapidly dispersed into interstellar space. These heavier elements, along with

H, He and the A < 56 elements (which include O, S, C, N, Fe, Mg, Ca, Al, Na,

and K - the dominant constituents making up the planets), can thereafter collect

into new nebulae (clouds) that may reorganize into additional stars, setting up

further nucleosynthesis. The elements were mostly created in the first few billion

years when rates of star formation, burning, and explosive destruction were higher

than present, but the process of element production still goes on. Elemental materials

not reincorporated in stars are available to organize into compounds that make

up the dust, gases, and particles from which planetary bodies are assembled.

As explained earlier, stars

capable of synthesizing the heavier elements are also larger and thus fated

to be destroyed explosively. In so doing, they expel and disperse the heavier

elements in mixes of dust particles and gases. These recollect over time in

nebular masses that become the new "nurseries" for later (younger) stars. Many

of those in turn will give off the heavier elements in surface expulsions as

Red Giants strip down and if large enough as supernovae. Thus the interstellar

space is continually gaining a new chemical mix of elements, tending towards

loss of hydrogen/helium and proportionately higher percentages of the elements

of the remainder of the Periodic Table. As more stars form, not only do they

contain some fraction of these elements but the associated dust/gas clouds may

by then have enough of those elements we associate with planets and organic

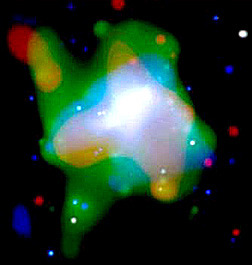

matter. There is growing evidence

that a significant fraction of the heavier elements were and are being produced

in the myriads of Dwarf Galaxies (most still undetected because of their reduced

luminosities) that pervade the Universe. Many of these undergo extended periods

of star formation and correlative supernovae bursts, releasing these elements

to intergalactic space. In this Chandra image of NGC 020724, a dwarf about 7

million light years away, giant bubbles of hot (10 million degrees) supernova

gases undergoing rapid expansion have been shown spectroscopically to contain

enrichments of oxygen, neon, magnesium and silicon.

Having now reviewed how

the elements are produced from Big Bang and subsequent stellar processes, we

should mention something about the relative abundances of the various elements

throughout the Universe. This turns out to be a difficult task for one obvious

reason. Spectroscopic measurements of elements from the distant stars are strongly

biased towards only those elements in excited states at or near the stellar

surface. Those elements principally in the interior do not contribute to surface

radiation in the same proportions as actually exist in a star. Only estimates

based on stellar interior models can be made. The situation is better for our

own star, the Sun. When element distributions are stated as Cosmic Abundances,

they actually are rough estimates made from Solar Abundances . And, the

latter abundances are not the same as the much better known Earth Abundances.

Below are two plots: Solar and Earth Abundances:

Note that the ordinate

for the Earth Abundance diagram is given in terms of mass fraction (all elements

together would make up 1, or 100%; note that Oxygen and Iron are the two most

abundant in/on/above the Earth). The Solar Abundance ordinate compares all elements

to Hydrogen (as scaled to an arbitrary H = 1012 atoms. We will take

a closer look at the left half of the Solar (Cosmic) Abundance curve with this

version

Several comments about

this (these) abundance plots are in order: First, the general trend is

towards ever decreasing abundances as the atomic number increases. Second,

there is a distinct zig-zag (up-down) pattern to the whole curve. For example,

between carbon and oxygen there is a decrease (the element is Nitrogen); between

neon and magnesium the decrease element is sodium; the largest drop is between

oxygen and neon, the element that thus decreases notably is fluorine. The reason

for this fluctuating pattern is just this: elements with odd numbers of nucleons

(protons and neutrons) are less stable, resulting in one unpaired (odd) proton

or neutron - those that pair these particles result in offsetting spins in opposite

directions that enhance stability (all this is part of the quantum theory of

nuclear arrangements). Third, there is a huge drop in abundance for the

Lithium-Beryllium-Boron (Li-Be-B) triplet. This results from two factors: 1)

At the Big Bang, nuclear processes that could fuse the proper H or He isotopes

into Li and/or the other two were statistically very rare and hence inefficient,

and 2) Some of the Li-Be-B that formed and survived may be destroyed in processes

with stars.

A somewhat easier task is

to compare stars and galaxies in terms of their metallicities - a ratio

of all amount of all elements with atomic numbers greater than 2 to the amount

of hydrogen present. Astronomers use the word "metal" differently from chemists.

A metal for a chemist includes only those elements in the Periodic Table labeled

IB through VIIIB. Astronomers simply include all elements (including those with

non-metallic properties) beyond He as "metals".

The "metal" composition

of the Sun is fairly well known. Actually, the measurements are made on the

chromosphere, the dominantly hydrogen gas which constitutes the solar atmosphere.

The source of spectral radiation, however, comes mainly from the photosphere.

The relative numbers of elements within the compressed body of the Sun is different,

but good estimates can be made based on element distribution models. One element

that gives many strong spectral lines is Iron (Fe). This element is chosen as

an indicator of the Sun's metallicity; it proxies for all metals whose amounts

tend to vary systematically with the iron concentration. Both the amount of

iron and of hydrogen present at the surface can be calculated from the strengths

of selected hydrogen and iron spectra derived from analysis of their absorption

lines as their quantized radiation passes through the chromosphere.

From these compositional data

a quantity determined as the ratio of amount of iron to amount of hydrogen (Fe/H)

can be calculated for the Sun. It is arbitrarily set = 1. Corresponding ratios

are determined for either individual stars or for galaxies (in which the Fe/H

depends on the gross or composite average of these two elements resulting from

radiation emitted by all stars, intragalactic gas, and halos within a given galaxy).

By convention, the Fe/H ratio values are expressed as log10 numbers.

This is a commonly used formula for comparing Fe/H ratios of stars to that of

the Sun:

Thus the Sun's Fe/H is

the log of 1 or 0. A star with a ratio of 1 to 100 yields a log value of -2;

this also means that the metals abundances are 1% of that established for the

Sun. A star whose log is +1 contains ten times as much metals as the Sun. Measurements

for thousands of stars have established that the range of log values is from

-4 (very metal-poor) to +1 (very metal-rich).

Some general observations

about the characteristics of stars as indicated by their metallicities: 1) the

disk portion of a galaxy has a range of metallicities, with Population I stars

having values > -1, i.e., towards smaller negative numbers to positive numbers

less than +1, whereas Population II stars have negative values beyond - 1; 2.

globular clusters and halo stars are metal-poor (values more negative than -1);

3) metal-rich stars are in the red segment of the Color Index and metal-poor stars

are blue; 4) although there can be complexities, in general metal-poor stars are

young in appearance (either near the outer limits of the Universe which show stars

that formed in the first few billion years after the Big Bang or stars formed

more recently from gas clouds that have had little contribution of heavier elements

from supernovae) and short-lived; 5) metal-rich stars from F, G, K, and M positions

on the Main Sequence are redder than stars of similar sizes (masses); and 6) dust

around a star will make it redder.

Overall, the rule of thumb

is just that a star will show a metallicity that depends on prior processes

that have changed the composition of the interstellar gas in the neighborhood

in which it forms. This is a function mainly of the number of supernovae that

have occurred previous to the formation of the star and the amounts of metals

each ejected that then became mixed into the cloud that supplies the star (and

other stars growing from this cloud). Since, over time the gas composition in

the interstellar medium should progressively enrich in metals, then those stars

that are metal-rich tend to have organized in later stages of a galaxy's history.

From the above it follows

that stars that are extremely metal-poor are likely to be first-generation and

thus primitive. HE0107-5240, a small star in our Milky Way some 36000 light

years from Earth, has an age estimated to be at least 12 billion years, making

it the oldest star examined to date. Here it is:

This star is extremely

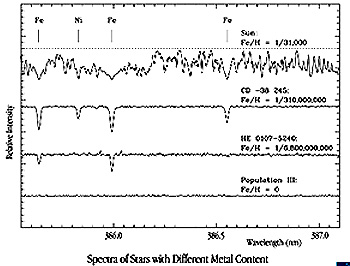

metal-poor, as indicated by this series of spectra:

The ratio of Fe atoms to

H atoms for the Sun is 1/31000. The Fe/H ratio for HE0107-5240 is dramitically

lower, 1/6,800,000,000. Its composition then indicates that it had to form early

in Universe history when enrichment of the heavier elements had scarcely begun

in consequence of numerous early supernovae. Metallicity has a practical

significance to this Earth's inhabitants. Life does not apparently form around

all stars from O to M types. It tends to develop around those stars that will

produce planets of the right composition. Thus, the degree of element abundance

and enrichment become a vital factor. The dust around a star has a composition

that is related to the extent of metallicity found in that star. Only a small

fraction of all the stars is likely to have a suitable metallicity that extends

to its surrounding dust and gases, such that planets with Earthlike conditions

are produced. We were lucky. Now, putting the above

information on element production in the context of the existence of thinking

organisms: Life on Earth (and probably elsewhere) is based on carbon and a few

other elements (principally H, N, and O, but smaller amounts of P, S, and traces

of Fe and other heavier elements). Where does the carbon come from? As we have

already alluded to, scientists generally agree that matter was originally present

in the form of hydrogen, and that heavier elements up to Fe were constructed

by fusing together hydrogen nuclei (protons) with neutrons and electrons. This

process involves the conversion of a small amount of mass to energy, according

to Einstein's E = mc2. In the 1930s, Hans Bethe showed that the energy

radiated from the sun and stars could be produced by either or both of two sequences

of nuclear reactions: (1) the "proton cycle" in which protons are fused to form

helium nuclei (each having 2 protons and two neutrons); (2) the "carbon cycle"

in which a carbon nucleus (6 protons and 6 neutrons) absorbs a helium nucleus

to form an oxygen nucleus. But there did not seem to be any way to get from

helium to carbon. The most obvious path would be to combine two helium nuclei

to produce an isotope of beryllium with 4 protons and 4 neutrons, but that isotope

is not stable (it takes one more neutron to produce a stable isotope) and calculations

showed that it would not last long enough to pick up another helium nucleus

to yield carbon. However, in 1953 Fred Hoyle predicted that the carbon nucleus

has an excited state with just the right energy to match the energy of beryllium

plus helium, producing a resonance which allows the reaction to produce carbon

in the interior of a star. His prediction was confirmed by experiments at CalTech,

and the helium --> beryllium --> carbon reaction is now considered a crucial

step in a more general scheme of nuclear reactions that produce all the heavier

elements. Hoyle later noted that his prediction was a successful application

of the "anthropic principle": the Universe must have the properties needed to

allow the evolution of life, otherwise humans wouldn't be here to study it.

If some of the physical constants had slightly different values, the carbon

nucleus would not have an excited state with the right energy to make this reaction

go, and carbon-based life (especially us) could not exist. As a bottom line aside,

remember what we commented on in page 20-1: that the atoms and molecules making

up everything on Earth including our own bodies have had a continuous existence

from varying time spans in Universe history. Many elements have originated in

supernovae that fed material from our galaxy into the cloud leading to the organization

of the Sun and its planets. Hydrogen in the organisms of Earth, and in you particularly,

may trace the beginning of many (perhaps most) of the individual atoms in today's

life forms to the Big Bang itself. We truly are Star People.

![]()

![]()

![]()