Before reading the next two

pages, it may be profitable for you to get an overview of Star formation

by reading a specific page from the above-cited Oregon lectures.

The number of stars in

the Universe must be incredibly huge - a good guess is 100 billion galaxies

each containing 100 billion stars or (1011 times 1011,

which calculates as 1022. Yet on a very clear night in dry air, one

sees without using a telescope or binoculars about 2000 "star" points outside

the Milky Way in the northern hemisphere and a similar number in the southern

hemisphere. Some of these are distant galaxies, so far away that the unaided

eye can discern only an apparent single light source.Man of the brightest stars

are generally those closest to the Sun (around 1 to 100 light years away). Only

when powerful telescopes are used does the astronomer realize by estimate or

extrapolation that billions of galaxies exist; by inference we deduce that these

probably contain stars in numbers similar to those that can be roughly counted

in the Milky Way (in the tens of billions). We begin this concentration

on stars with something that is itself not truly a scientific topic but which

remains useful to astronomers as a convenient "Sky Map". Such maps contain the

Constellations - patterns of certain visible stars (a few were actually

galaxies but this was not known at the time) that the ancients imaginatively

discerned in looking at individual stars within narrow patches of the celestial

hemisphere which seemed to be distinctive and readily recognized. These arrangements

were given fanciful names, of gods, animals, and other descriptors from their

everyday experiences. This began with the Babylonians in Mesopotamia, and the

system was expanded to 88 named constellations by the Greeks and Romans some

2000 years ago. (Psychics and Fortune Tellers have used constellations as "signs"

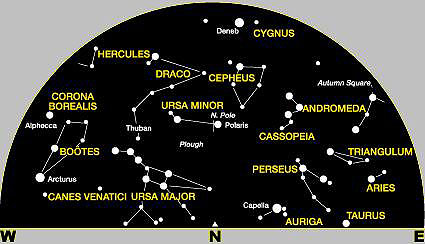

and for horoscopes for several millenia.) This next pair of illustrations (source

StarNames) shows

some of the major constellations in the northern hemisphere, plotted in two

half circle fields:

To the ancients, the stars

were all equidistant on the "celestial sphere" and varied only in brightness.

Modern astronomers now know that individual stars/galaxies in the light points

that make up the constellation pattern are actually located at various distances

from Earth, which together with diifferences in size account for their different

brightnesses. Most of the defining stars in a constellation are located in our

galaxy, the Milky Way. Astronomers often cite

individual constellations as a reference framework in specifying the location

in the celestial sphere of some stellar or galactic feature or phenomenon on

which they are reporting. However, they need to give some specific hemisphere

coordinates, either in terms of azimuth, altitude (along a meridian) and hour

time, or in another system, the declination and right azimuth. The position

of any star as seen on some specific night will vary with the hour, time of

year, and geographic location of the observer. Thus, the movement of the Earth

around its axis causes the stars during a night's observation to follow arcuate

(circles) paths around a part of the sky where the celestial pole is located

(close to the North Star pointed to by two stars in the Big Dipper [Ursa Major]).

The groups of constellations also shift with the seasons and with the place

on Earth where the star-gazer is positioned (different constellations are seen

by those in the Southern Hemisphere of the Earth than those in the Northern

Hemisphere [lookers at the Equator will see some of the constellations visible

in each Hemisphere]). More about the constellations can be found at the Star Charts and Star Map

Internet sites. For the second site, after it appears scroll down until you

see in a sentence an underlined phrase called "northern hemisphere constellations",

an example of the usual format of such maps (this one is valid for December).

This next map, also from StarNames, shows the same look direction (to the North),

as the first map above, but is a Winter view (compare and locate equivalent

constellations; but now several have disappeared and new ones have appeared).

Interesting, but back to Science.

The standard model for a star is, of course, our Sun. The Sun is typical of most

stars; as we shall note shortly, these stellar bodies vary from about 0.1 to 100

times the mass contained in the Sun. Without a telescope, under exceptional viewing

conditions (using binoculars), about 9000 individual stars can be seen in the

wide celestial band that is the central disc of the Milky Way (M.W.) galaxy. Others

elsewhere in the celestial hemisphere make up about 2000 points of stellar light

can be seen (in clear air, away from urban light contamination) by the naked eye.

Some are nearby within our galaxy and are not particularly large, while others

are mostly stars of the Giant/Supergiant types in the halo (see below) around

the Milky Way. Still others are galaxies that lie in intergalactic space beyond

the Milky Way but mostly within a billion light years from Earth. Telescopes can

resolve countless more stars in the M.W., can recognize millions of galaxies,

and can pick out some individual stars in nearby galaxies.

A degree of luminosity of

an object in the sky (galaxy; star; glowing clouds; planet) can be represented

by its apparent magnitude - a measure of how bright it actually

appears as seen by the telescope or other measuring device. This magnitude is

a function of 1) the intrinsic brightness which varies as a function of size,

mass, and spectral type (related to star's surface temperature)and 2) its distance

from Earth. (Magnitude as applied to a galaxy, which seldom shows many individual

stars unless they are close [generally less than a billion years away], is an

integrated value for the unresolved composite of glowing stars and gases within

it.) The brightness of a star can be measured photometrically (at some arbitrary

wavelength range) and assigned a luminosity L (radiant flux). For two stars (a

and b) whose luminosities have been determined, this relationship holds:

from which can be derived:

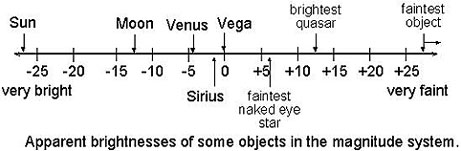

To establish a numerical

scale, some reference star(s) must be assigned an arbitrary value. Initially,

the star chosen, Polaris, was rated at +2.0 but when it was later found to be

a variable star, others were selected to be the 0 reference value for m. The

magnitude scale ranges from -m (very bright) to +m (increasingly faint) values.

The more positive the number, the fainter is the object (planet; star; galaxy);

very distant galaxies, even though these may be extremely luminous, could have

large positive apparent magnitudes because of the 1/r2 decrease in

brightness with increasing distance. The Sun has the value - 26.5; the full

Moon is -12.5; Venus is -4.4; the naked eye can see stars brighter than + 7;

Pluto has a magnitude of +15; Earth-based telescopes can pick out stars visually

with magnitudes down to ~+ 20 (faintest) and with CCD integrators to about +28,

and the HST to about +30. Thus, the trend in these values is from decreasing

negativity to increasing positivity as the objects get ever less luminous as

observed through a telescope. Each change in magnitude by 1 unit represents

an increase/decrease in apparent brightness of 2.512; a jump of 3 units towards

decreasing luminosity, say from magnitude +4 to +7, results in a (2.512)3

= 15.87 decrease in brightness (the formula for this is derivable from the above

equations, such that the ratio of luminosities is given by this expression:

10(0.4)(mb - ma). Below is a simple linear

graph that shows various astronomical objects plotted on the apparent magnitude

scale:

Absolute magnitude (M) is

the apparent magnitude (m) a star would have if it were relocated to a standard

distance from Earth. Apparent magnitude can be converted to absolute magnitude

by calculating what the star's or galaxy's luminosity would appear to be if it

were conceived as being moved to a reference distance of 10 parsecs (10 x 3.26

light years) from Earth. The formula for this is:

where r is the actual

distance (in parsecs) of the star from Earth. Both positive and negative values

for M are possible. The procedure envisions all stars of varying intrinsic brightnesses

and at varying distances from Earth throughout the Cosmos as having been arbitrarily

relocated at a single common distance away from the Earth. Both luminosity and magnitude

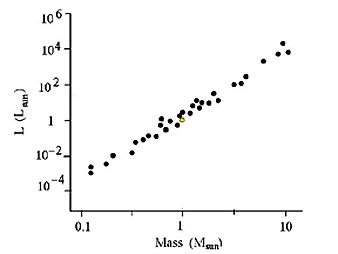

are related to a star's mass (which is best determined by applying Newton's

Laws of motion to binary stars [a pair; see below for a discussion of binaries]).

The graph below, made from astrometric data in which mass is determined by gravitational

effects, expresses this relationship; in the plot both mass and luminosity are

referenced to the Sun (note that the numbers are plotted in logarithmic units

on both axes):

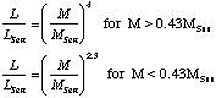

There is a relationship

between absolute magnitude (here given by L for luminosity) and mass (given

by the conventional letter M; which accounts for replacing the absolute magnitude

M with L). Here is one expression:

In the above, both L and

M for a given star are ratioed to the values determined for the Sun. Note the

two different power exponents. It seems that some stars obey a fourth power,

others a 3, and a few are just the square of the mass. The most general expression

in use is given as L = M3.5. There are relatively few stars with

mass greater 50 times the Sun. Very rarely, we can find a star approaching 100s

solar mass, but these are so short-lived that nearly all created before the

last million years have exploded, with their mass being highly dispersed, and

thus ceasing to send detectable radiation. If the Sun were envisioned

as displaced outward to a distance of 32.6 l.y., its apparent magnitude as seen

from Earth would be -26.5; its absolute magnitude would be changed to +4.85.

A quasar, which is commonly brighter than a galaxy, has an absolute brightness

of - 27 (note that in the absolute scale increasingly negative values denote

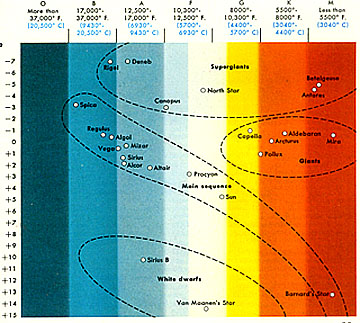

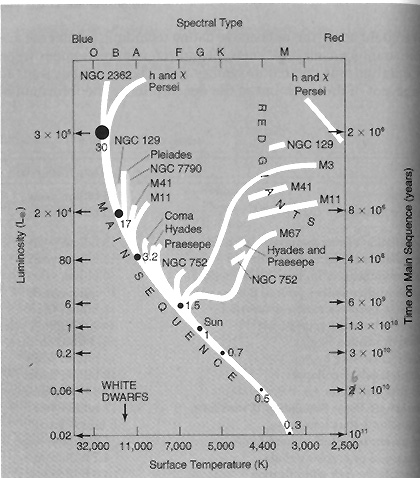

increasing intrinsic brightness). The illustration below gives the absolute

magnitudes (vertical axis) as a function of temperature (horizontal axis) for

a number of stars with popular names; note the similarity of the color bars

(which express the visual colors of the stars as seen through a telescope) to

the brightness range - this is essentially a preview version of the standard

H-D diagram, shown and discussed on this page beginning twelve figures below

this, which serves as a plot of the different types of stars and an inferred

history of a star of given size (mass):

One classification of stars

is that of setting up categories of star types (see below) in a series of decreasing

sizes and luminosities. These are the 7 Luminosity/Type Classes: Ia, Ib: Extreme

Supergiants; II: Supergiants (Betelgeuse); III: Giants (Antares);

IV: Subgiants; V: Dwarfs (Sun): VI: Subdwarfs (metal poor);

VII: White Dwarfs (burned out stars). The oddity in this classification

is the omission of a category of "Normal"; a star is either a Giant or a Dwarf.

Another classification is based on density. Starting with the least dense

and progressing to the most dense (massive), this is the sequence: Supergiant;

Red Giant; Main Sequence; Brown Dwarf; White Dwarf;

Neutron Star; and Black Hole. Each of the above bold-faced types

are described in some detail on this two-part page.

The brightest star in the

northern hemisphere of the sky is Sirius, an A type star (see the H-R plots

below and accompanying paragraphs which explain the letter designation of stars)

of apparent magnitude -1.47 that lies 8.7 light years away. Here is how it appears

through a telescope:

Closest to the Sun is an

M type star (faint), Proxima Centauri, being 4.2 light years away. Just slightly

farther away is Alpha Centauri, a G type star that is the third brightest in

the heavens (visible in southern hemisphere). Here is a telescope view of Alpha

Centauri:

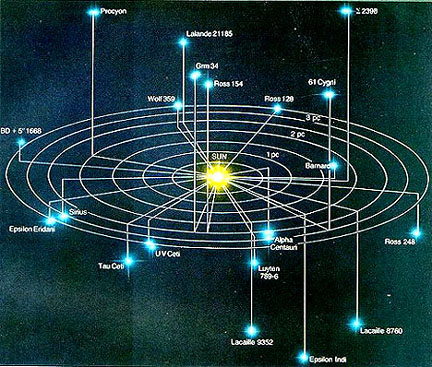

The map below is a plot

of the distances from Earth (circle is 13.1 light years in radius) of the 25

nearest individual or binary stars or local clusters in our region of the Milky

Way Galaxy:

Information Bonus: Just

beyond this limit is the star Vega (27 light years away). It has two claims

to fame: 1) it alternates with Polaris as the North Star used in navigation;

the Earth's precession brings Vega into this position every 11000 years, and

2) It was the nearby star used as the host for an extraterrestrial civiliation

in Carl Sagan's extraordinary science fiction novel "Contact" (later made into

the movie of the same named "starring" Jodie Foster); contact was made with

a planet near Vega as a signal picked up by the Socorro, NM radio telescope

array - as initially interpreted that signal consisted of a string of prime

numbers (those divisible only by themselves and 1).

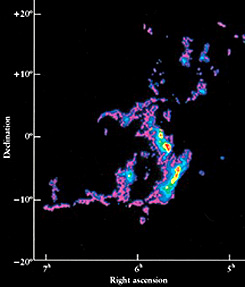

Referring to the above, the

following is extracted verbatim from the caption accompanying this image

that was displayed on the Astronomy Picture of the Day Website for February

17, 2002: What surrounds the Sun in this neck of the Milky Way Galaxy? Our current

best guess is depicted in the above map of the surrounding 1500 light years constructed

from various observations and deductions. Currently, the Sun is passing through

a Local Interstellar Cloud (LIC), shown in violet, which is flowing away from

the Scorpius-Centaurus Association of young stars. The LIC resides in a low-density

hole in the interstellar medium (ISM) called the Local Bubble, shown in black.

Nearby, high-density molecular clouds including the Aquila Rift surround star

forming regions, each shown in orange. The Gum Nebula, shown in green, is a region

of hot ionized hydrogen gas. Inside the Gum Nebula is the Vela Supernova Remnant,

shown in pink, which is expanding to create fragmented shells of material like

the LIC. Future observations should help astronomers discern more about the local

Galactic Neighborhood and how it might have affected Earth's past climate.

The largest star so far

measured in the Milky Way is Mu Cephi (in the galactic cloud IC1396), seen as

the orange disc (also called Herschel's Garnet star) near top center of this

HST image. Located about 1800 light years from Earth, it is almost 2500 times

the diameter of the Sun.

This is an example of a

rare type of star known as a hypergiant (see next page). Another even bigger

star (2800 times the solar diameter; 2.4 billion miles) is Epsilon Aurigae (in

the constellation Auriga, the Charioteer), but residing in the Milky Way about

3300 light years from Earth. This star, also known as Al Maaz (Arabic for he-goat)

and visible to the naked eye) is considered by many astronomers to be the "strangest"

star in the firmament. Every 27 years this star (magnitude 3.2) undergoes a

diminishing of brightness (about 60000 times greater than the Sun) lasting about

2 years. The last such event was in 1983; the next in 2010. It is thus one of

a class called "eclipsing stars". The cause of this regular pattern of luminosity

change is still uncertain; some astronomers think it is caused by the passage

of a second massive star across Epsilon Aurigae's face but that binary is so

far undetected, leading to the hypothesis that the drop in luminosity occurs

when a cloud of dark material (dust) orbiting the star as a clump obscures Epsilon

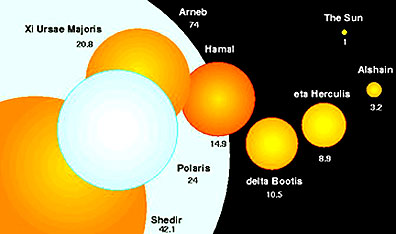

Aurigae each time it moves through the line of sight to the Earth. Most stars bigger than

the Sun are not as huge as Mu Cephi or Epsilon Aurigae. The majority are no

larger than about 100x the diameter of the Sun. This diagram illustrates the

relative size of some common stars (setting the Sun's diameter as 1), which

establishes our star as rather ordinary in the size scheme within the Milky

Way:

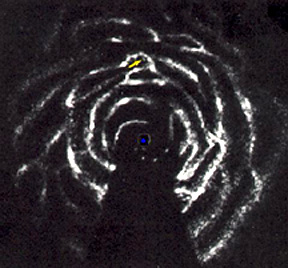

More than half of the stars

in a galaxy are also tied locally to a second star as a companion (binary),

such that each of the pair or group orbits around a common center in space determined

by their mass-dependent mutual gravitational attraction. This arrangement is

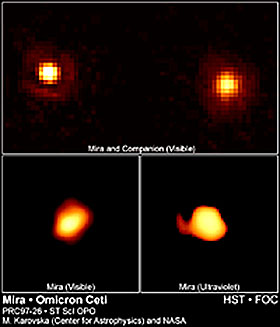

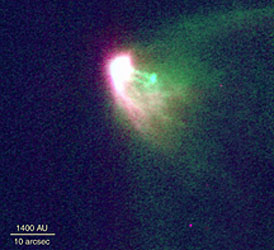

exemplified by the image made by the HST Faint Object Camera (FOC) of the Mira

star (Omicron Ceti) in the Constellation Cetus.

This star is a Red Giant

(see below) which appears to be periodically brightening (it is credited as

the first known variable star, having been discovered in 1546 A.D.). The HST

has resolved it into a binary in which the star on the left has a White Dwarf

(see below) at its core and now receives mass from the Red Giant that accumulates

until the hydrogen burns (see first illustration at the top of page 20-6). An ultraviolet

(UV) image made by HST's FOC actually shows mass being drawn off the Red Giant. Some stars are grouped

into more than one companion; ternary groupings (three stars orbiting about

a common center of gravity) are fairly common. Here is an image of four stars

orbiting as a unit about a gravity center in the galaxy M73.

Binary star systems are recognized

by three means: 1) visual, through a telescope (as in the above two images); 2)

by periodic drops in brightness caused by passage of one star across another (eclipse;

an uncommon observation condition); and 3) by measuring spectral characteristics

in which both a Doppler shift towards the red and the blue occur as one star moves

away and the other towards Earth (and the reverse) along pathways of their mutual

orbits.

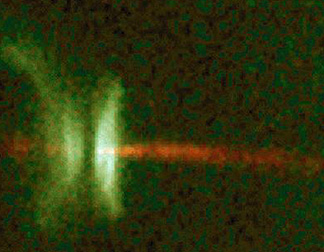

To demonstrate the second

means, examine this diagram which shows the brightness levels (and magnitude

variations) for the binary star Algol:

The larger star (in blue)

is mutually orbiting a smaller star (red) which has a notably smaller output

in its own luminosity. When the latter star passes in front of the larger star,

there is a notable drop in the combined luminosities, as the partial eclipse

cuts out some light from the larger star. Then, when the red star passes behind

the blue star, there is a small drop in luminosity since the smaller, now occulted

star does not send any of its light to the observing telescope. Spectral line shifts are

used to study the motions of binary stars. We will treat stellar spectroscopy

in detail on page 20-7

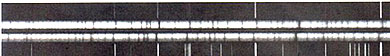

As a preview, the spectral method can be illustrated by looking at a pair of

spectral strips for two similar stars that are mutually orbiting:

Bright lines for hydrogen

appear in the top and bottom (dark background) strips. This fixes a reference

location for excited hydrogen in the rest state. The two center spectral strips

include the same hydrogen lines, the first strip acquired from one and the second

the other star. Note that the lines in one have moved to the left and the other

to the right of the reference lines position. The spectrum on the bottom center

has been blueshifted (see page

20-9) towards shorter wavelengths; the spectrum at the top center has been

redshifted towards longer wavelengths. This is explained thusly: The bottom

star is in motion towards the observing system on Earth whereas the top star

is moving away from the telescope. This would occur when the two stars are aligned

sideways to the line of sight and are moving in opposite directions around a

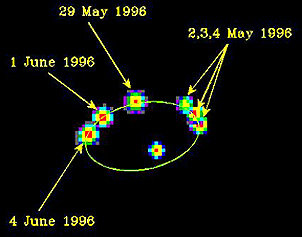

common center of gravity. For some visual binaries,

movements over time can be observed and plotted, such as illustrated here for

the star Mizar (in the Ursa Major constellation), which is resolvable into Mizar

A and Mizar B.

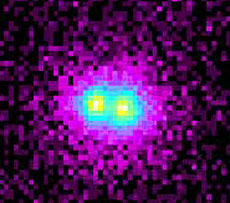

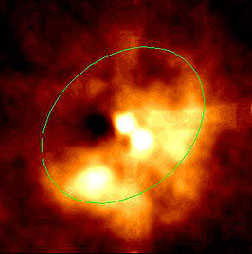

The Chandra X-ray Observatory

has imaged a close binary pair in the M15 Galaxy. Prior to obtaining this image,

the object was thought to be a single star, but at x-ray wavelengths, it is

now resolved into a faint blue star and a nearby companion believed to be a

neutron star giving off high energy radiation. Thus:

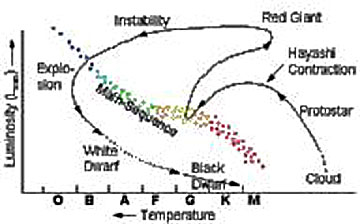

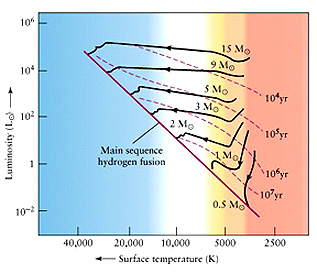

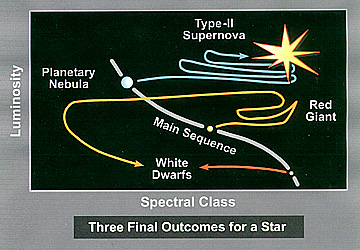

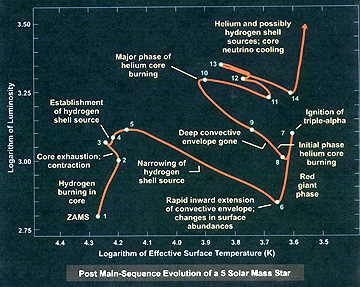

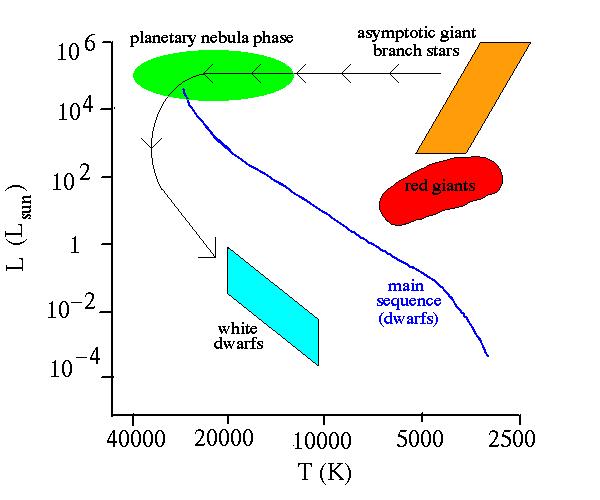

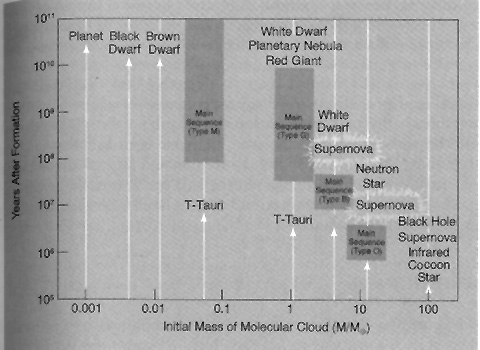

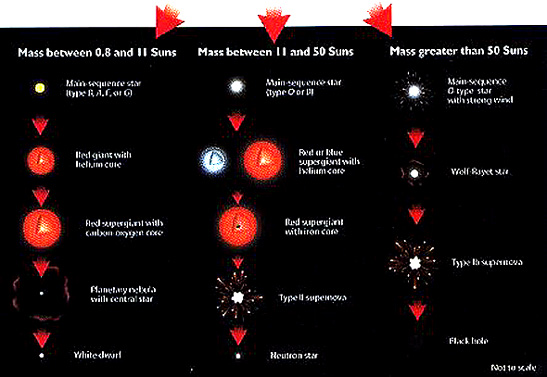

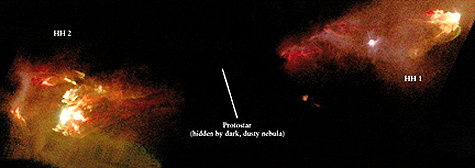

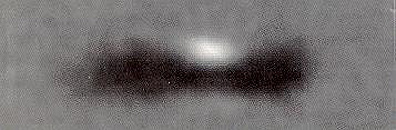

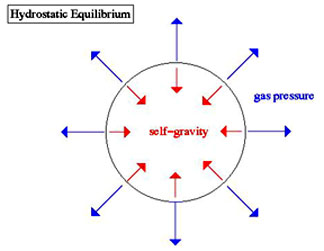

Turning now to stellar evolution,

to preview what will be examined in some detail (shown in chart form later on

this page), the pattern of a star's history follows a pathway that, depending

on its total mass, eventually splits into one of two branches (/> or \>),

as it leaves what is known as the Main Sequence. This is: Development of a large

cloud of denser gas made up of predominantly molecular hydrogen (H2)

+ dust --> Protostar --> T-Tauri Phase --> Main Sequence /> (if mass

less than 8 solar masses)--> Red Giant --> Planetary Nebula --> White

Dwarf; OR \> (if mass greater than 8 solar masses) --> Supernova -->

Neutron Star and/or Black Hole (depending on mass [size]).