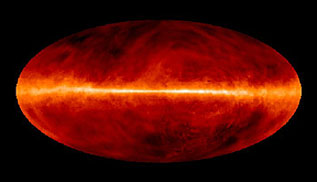

Astronomers at NASA's Goddard

Space Flight Center have assembled images taken at various regions of the spectrum

by instruments (ground and space based telescopes, etc.) looking at our galaxy

the Milky Way, as depicted in this montage (this is not a view of the M.W. taken

externally but one looking towards its center and beyond towards its far edge;

thus that part of the M.W. lying behind us [further from the center] is not included.

Below, each image is identified by its imaging wavelength or wavelength interval

of the spectrum, together with a brief description of the principal information

that is associated with data collected from that region. Starting from the top:

(1) Atomic Hydrogen

(1420 Mhz): Picks out radiation from excited neutral hydrogen in interstellar

gas and dust clouds.

(2) Radio Continuum

(480 Mhz): Signal produced by fast-moving electrons; good for spotting sites

of now diminished supernovae.

(3) Molecular Hydrogen

(115 GHz): Shows distribution of molecular hydrogen associated with carbon

monoxide in cold interstellar matter.

(4) Radio Continuum

(2.4-2.7 GHz): Caused by high energy electrons and associated warm, ionized

gases.

(5) Far-Infrared (12-100

µm): Radiation emanates from dust heated by stellar radiation; emphasizes

active star-forming regions.

(6)Mid-Infrared (6.8-10.8

µm): Due to excitation of complex molecules in interstellar clouds and in

cooler reddish stars.

(7) Near-Infrared (1.25-3.5

µm): Reveals temperatures, mainly of Giant, relatively cool stars, and shows

the galactic core; dust is "transparent" in this spectral region and does not

obscure many luminous features.

(8)Visible Light (0.4-0.5

µm): Displays primarily nearby stars and thin ionized gas; dark areas cold.

(9) X-Rays (0.25-1.5

kiloelectron-volts): Reveals gases heated by shock waves from supernovae.

(10) Gamma-Rays (300

megaelectron-volts): Pinpoints high energy sources coming from pulsars or

phenomena stemming from cosmic-rays. More information about

these images is presented at this Goddard Multiwavelength Astronomy

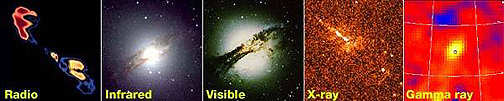

site. This idea of imaging cosmological

entities at different wavelengths can be further enforced by looking at the

montage of five views of the star Centaurus A in the wavelength regions indicated

on each panel.

A point to be kept in mind

in looking at images below, as well as on preceding and subsequent pages: Images

acquired in any of the specific regions of the EM spectrum do not necessarily

look the same - some may appear notably different than others because of the

way in which the image is processed and displayed (for example, different filters

may be used or the image values for intensity may be rendered in color-coded

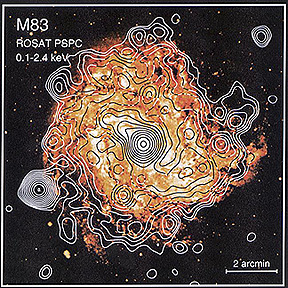

levels assigned different colors). Now, some additional examples

of observations in specific regions of the spectrum: First, let us look at high

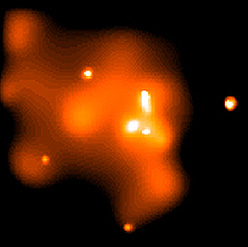

energy radiations in the X-ray region. The first image below shows the spiral

galaxy M83 as it appears (in a colorized rendition) optically. Against this

are contours of varations in x-ray intensities (given in units of keV [kilo-electron

volts]) as measured by the joint U.S.- German Rosat (Roentgen Satellite) launched

on June 1, 1990 to monitor the entire sky. Note the close-spaced contours around

the galaxy center, but several other x-ray "hot spots" are also evident.

Several mechanisms account

for this x-ray generation. Most prevalent is excitation into ionized states

of intragalactic gases between stars or gases between galaxies that, in the

tenuous void separating the stellar bodies, are traveling at such high velocities

that they represent temperatures in excess of 1,000,000 °K capable of producing

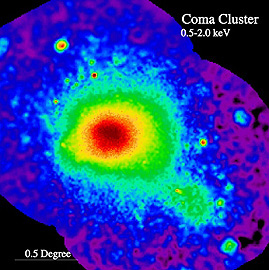

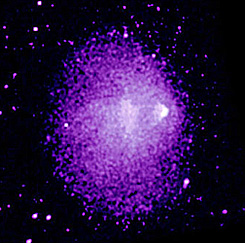

strong x-ray responses. The second Rosat image

portrays x-ray variations spread over the entire Coma supercluster, comprised

of well over 1000 bright galaxies, located some 300,000,000 light years away.

X-ray intensities vary from strong in reds to decreasingly weaker in greens

to blues and purples. The interstellar gases emitting this radiation make up

about 10% of the total mass of the supercluster, along with 2% more in the stars

found in the individual galaxies as determined from optical measurements; the

remainder of the mass is presently unaccounted for after inventories across

the spectrum are related to their sources, so that the bulk of the mass is presumed

associated with dark matter (see page

20-9). Thus, examining both galaxies and intergalactic regions using radiation

at wavelengths both shorter and longer than the visible helps to quantify the

distribution of the entire mass of the Universe.

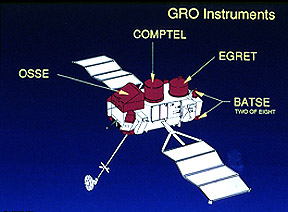

On April 5, 1991 NASA launched

the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO) as a complement to the HST that extends

coverage into the short wavelength, high energy end of the EM spectrum. It carried

four instruments that could measure radiation whose energies range from 30 MeV

to 30 GeV. This huge (central part nearly the size of a school bus) sensor platform

has been one of the most productive astronomical observatories orbited so far.

It is shown in this artist's drawing:

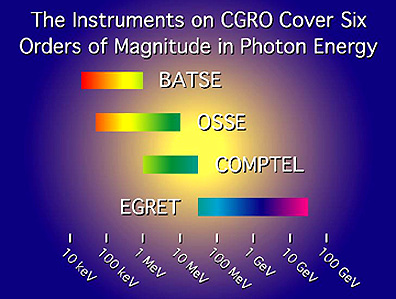

The individual range of

coverage by the CGRO sensors is shown in this plot:

The acronyms stand for

BATSE = Burst and Transient Source experiment; COMPTEL = Imaging Compton Telescope;

EGRET = Energetic Gamma Ray Experiment Telescope; OSSE = Oriented Scintillation

Spectral Telescope. (The CGRO was named to honor Dr. Arthur Holly Compton, an

eminent physicist, Nobel Laureate, and Chancellor of Washington University when

the writer [NMS] was a graduate student there).

The CGRO was designed to measure

radiation associated with stars and galaxies which result from high energy, usually

nuclear processes. It looked particularly at supernovas, quasar and pulsar emissions,

black hole accretions and other powerful stellar processes (next paragraph). CGRO

discovered a new class of energetic objects, called blazars, that give

off energy in the 30 MeV-30-GeV range.

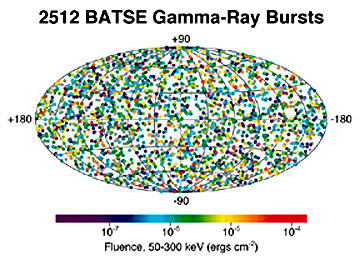

One prime astronomical

target of the CGRO was to search for Gamma Ray Bursts (GRBs), which are huge

releases of energy that are short-lived and variable, are widespread in the

celestial sphere and occur mainly in galaxies. Here is a map of those bursts

measured over time by CGRO; the local effects of the Milky Way bursts have been

removed. These GRBs will be discussed in more detail at the bottom of page page 20-6.

The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory

was a major achievement guided by astrophysicists and operated by NASA Goddard.

You can learn more about its results, with many additional images, at the CGRO site. On June 4, 2000 the CGRO was

deliberatly decelerated so as to enter the atmosphere over the Pacific, as its

orbital decay (adjustment fuel exhausted) meant it might fall to Earth at any

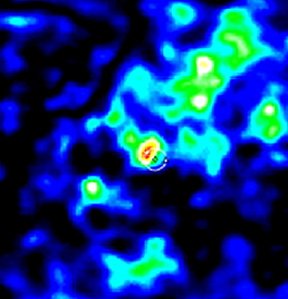

time soon, possibly threatening populated areas. A star in the Vela galaxy

is a typical example. As seen by Rosat, it looked like this:

When variations in x-ray

intensities are determined and displayed by color coding, this results:

CSRO provided this image

in which the energy levels are color-shaded:

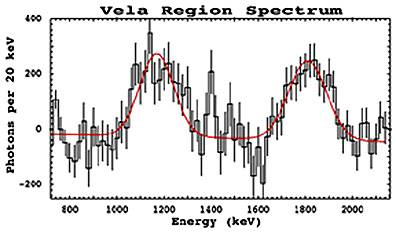

That energy spectrum can

be quantified for this object, as shown in this plot:

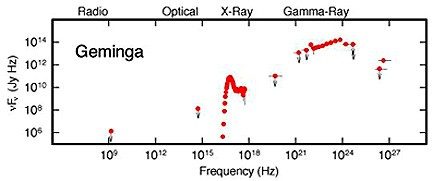

A plot based on frequencies

(which can be converted to energies) was obtained for the pulsar Geminga:

In September of 1999, NASA,

guided by scientists from several nations, launched the Chandra X-ray (Telescope)

(CXO). Named after the late S. Chandrasekhar, a reknown astronomer from India,

Chandra is managed by the Marshall Space Center. Its length, when fully deployed,

is 13.6 m (45 ft). It carries 4 sensors: a charge-coupled imaging spectrometer,

a High Resolution camera, and High and Low Energy gratings.Its spatial resolution

is 8 times greater than the best previous X-ray observatory and can pick out objects

20 times fainter as sources of x-radiation. Its astronomical targets include quasars,

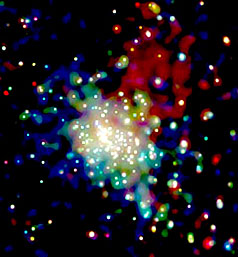

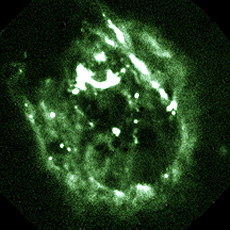

supernova and other high energy-emitting objects. Here is an example of an image

of a ring of x-radiation associated with the remnants of a supernova in the Constellation

Tucane:

Chandra has made images

of regions of more recent star formations (sometimes as bursts) in the Milky

Way. This one is striking indeed.

The Milky Way galaxy has

a powerful x-ray source at its center probably associated with material infall

into a Black Hole, as imaged thusly:

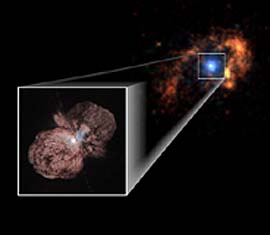

Imaging in the x-ray region

of the spectrum commonly picks up a completely different picture of the object

being imaged in the visible or other regions (see page I-3). This is exemplified

by this artist's reworking of the visible and x-ray renditions of Eta Carinae

in the Milky Way galaxy. The Chandra view shows an outer ring of high energy particles

not having any obvious counterpart in the HST image.

When the Carina nebula

is imaged using narrow band filters, it looks like this. The blue image used

to construct a color composite results from excitation of oxygen in the nebular

gases; green represents hydrogen in this rendition; red is associated with sulphur

ions.

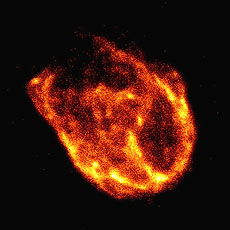

We emphasize these points

with these three views: Visible (top); X-Ray (middle); Radio Wave (bottom) segments

of the EM spectrum, for a exploded star in the nearby Large Magellanic Cloud

(a nebular satellite galaxy)

Because Chandra measures

x-radiation from its targets over a range of wavelengths, individual elements

which give off x-ray spectra at specific wavelengths can be detected and mapped.

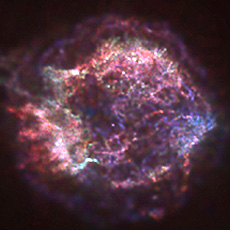

This has been done for the supernova Cassiopeia A. An HST optical image of this

exploding star looks like this:

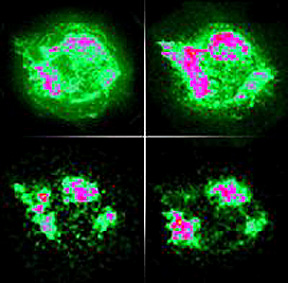

Here is a four panel set of

Chandra images of Cassiopeia A (see also page 20-6). The upper left

is color density map of the broad band radiation from Cassiopeia A. The upper

right focuses on Silicon emission lines; the lower left on Calcium; and the lower

right on iron. Thus Chandra is an adept tool for determining the distribution

in the expelled material of various elements that were produced by nuclear burning

in the star.

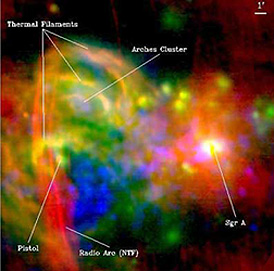

Chandra has explored our

Milky Way galaxy as well. This next image shows part of the central core region

of the galaxy (about 400 light years wide) in which a number of very bright

objects, seen in x-radiation, correspond to high energy emissions where interstellar

gases are drawn into white dwarfs, neutron stars, and possible black holes.

becoming continuously "ignited".

A spectacular image of

part of this central region was made by the Advanced CCD Spectrometer on Chandra:

In December of 1999, the

European Space Agency launched an even more powerful x-ray telescope known as

XMM-Newton (XMM stands for X-ray Multi-Mirror). Here are two colorized images,

the first showing the variations in x-ray intensities in several of the Hickson

group of stars and the second showing details of a supernova explosion in the

nearby Large Magellanic Cloud:

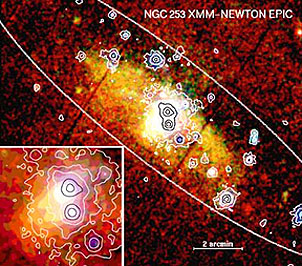

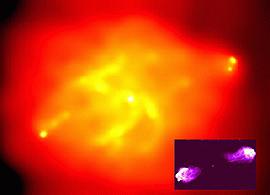

XMM-Newton has demonstrated

that large x-ray energy bursts also associate with the starbursts that mark

development of young stars. Here is an image of NGC253, some 8 million light

years from Earth; the inset on the left is a closer look at its center.

Satellites began to examine

the UV region of the sky with the OAO series (OAO-3 was named Copernicus) in the

late 1960's. The follow-on International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE) program began

in 1978. Copernicus led to maps of bright UV stars such as this:

The ultraviolet (UV) region

of the spectrum, from 70-2000 (0.007 - 0.2 µm) (Far) to 2000-4000 Angstroms

(0.2 - 0.4 µm) (Near), has provided interesting images of stellar bodies, including

the Sun. It also contains many diagnostic spectral lines helpful in determining

elemental composition. This next image shows the Earth as imaged by EUVE (Extreme

UltraViolet Explorer, launched in 1992 and operating until February, 2001; imaging

from 70 to 760 Angstroms). It shows excited helium (yellow) and hydrogen (orange)

in an auroral field extending well beyond the solid Earth.

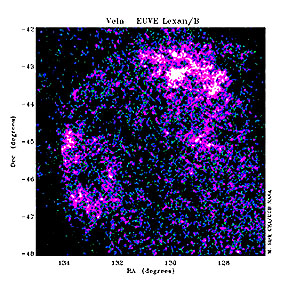

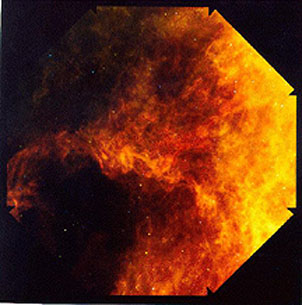

Looking outward into space,

the EUVE provided this image of the Vela Supernova:

One of the first UV telescopes

is the IUE (International Ultraviolet Explorer) launched jointly by ESA and

NASA in 1978; it operated into 1996. This is a UV image of the galactic source

NGC1680:

The Ultraviolet Imaging

Telescope (UIT) was flown as part of Astro-1 and Astro-2 lab packages on Shuttle

STS-35 and STS-67 in the mid-1990s. The telescope covers the UV range between

1200 and 3200 Angstroms. It is particularly adept at recognizing hot, young

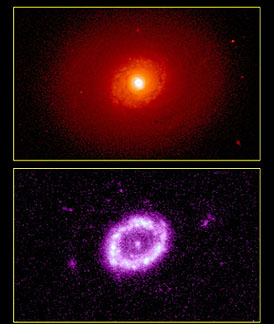

stars which give out strong UV radiation. The difference in appearance between

visible and ultraviolet images is pronounced in this UIT view of the galaxy

M94:

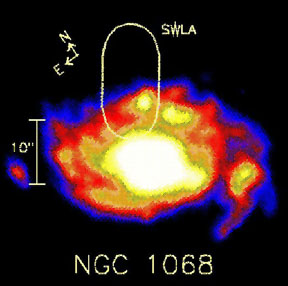

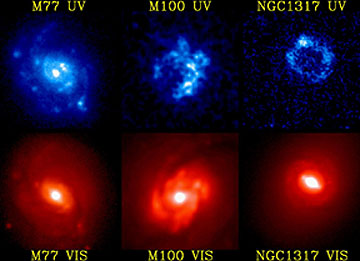

This next image shows three

galaxies in UV (top) and Visible (bottom); note the structure of the spiral arms

as brought out by molecular hydrogen excitation

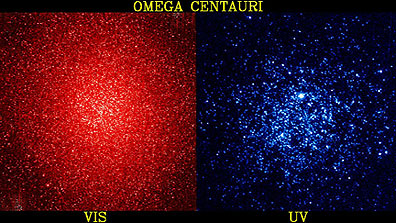

In this UIT image, the

globular cluster Omega Centauri in visible light appears to consist of mainly

red to orange stars, typical of older stellar bodies. But, the UV on the right

shows that there are also many younger, hotter stars.

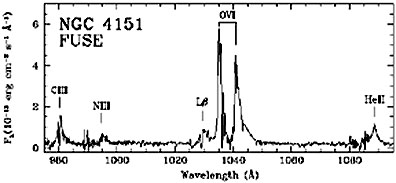

Launched on June 24, 1999,

FUSE (Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer) gathers spectra in the interval

910 - 1180 Angstroms. Excitation of molecular and elemental species in a star's

atmosphere or a galaxy en masse in this interval provides valuable information

about stellar processes. Here is a typical spectral plot obtained by FUSE from

observing a galaxy.

Observations through the

FUSE telescope can be converted to images, such as this:

FUSE's primary goal has

been to trace the history of the early Universe by monitoring the distribution

of hydrogen, deuterium, and helium in the intergalactic medium. Preliminary

results indicate that helium, formed in the first minute of the Big Bang, and

then dispersed during the expansion, will prove a sensitive indicator (it is

also well monitored by FUSE) of the inhomogenieties in the expanding Universe

following the initial explosion. Thus, the UV is proving

to be an optimum segment of the EM spectrum to study conditions in the so-called

empty space which actually contains hot interstellar gas. CHIPS (Cosmic Hot

Interstellar Plasma Spectrometer) is an astronomy satellite to be launched in

December 2002. It will measure the diffuse extreme ultraviolet glow that will

better define the properties and physical processes associated with the interstellar

medium. The UV carries to the Visible

spectral range. Just beyond the Visible is the Infrared, extending from about

1 to 1000 µm. Much of the interval coincides with the thermal IR which you studied

in Section 9. Hot stars are strong emitters in the IR and can be studied both

as images and from their spectra. Other astronomical features amenable to IR

observations include properties of accretionary disks and interstellar clouds,

the structure of the H II type stars (those in an early stage of development

that contain significant ionized hydrogen in the inner part of the hydrogen

gas cloud that is the source of their nuclear fuel), and the dynamics of the

Milky Way.

Small dark interstellar dust

that obscures stars in the Visible are called Bok Globules (discovered by a Dutch

astronomer of that name. They represent nebular gas and dust nearing the protostar

phase (see page 20-5); such molecular hydrogen clouds are very cold (-263°C) and

generally because of their small size (about a parsec) produce only one to several

stars. These globules (some of which can be nearly spherical) stand out best in

images that extend into the Near IR, as exemplified by this photo taken through

the Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT):

These two photos (acquired

by ESA's New Technology Telescope) show details of a Bok Globule in Barnard

68. The left image is made from three bands in the visible; the right image

consists of bands at 1.25 µm = Blue; 1.65 µm = green; and 2.16 µm = red, which

renders the cloud now transparent so that stars behind it become visible.

A galaxy (NGC2024) that

is still largely shrouded by dust looks much like a visible image in this version

made by the NICMOS camera on HST. The color composite consists of Blue = J band

(1.6 µm); Red = K band (2.2 µm); and Green = J and K combined.

One of the first infrared-dedicated

satellites was IRAS (Infrared Astronomical Satellite) launched in January of

1983. Its sensors were tuned to the 12, 25, 60, and 100 µm IR wavelengths. During

its lifetime, IRAS discovered more than 350,000 previously undetected IR objects

in the sky. This color composite of the interstellar "cirrus" clouds made up

of gas and dust grains in the Milky Way that occupy a wide field centered on

the North Celestial Pole is constructed from Blue = 12; Green = 60; Red = 100

µm.

On a grander scale, look

at this IRAS image of the now familiar neighbor, the Andromeda Galaxy, with

color-codes indicating variations in thermal emission at 12 µm.

IRAS obtained IR imagery

of the Milky Way. In this next image, the central part of the galactic plane

is displayed. Much of the yellows and oranges is thermal radiation from dust

that obscures individual stars.

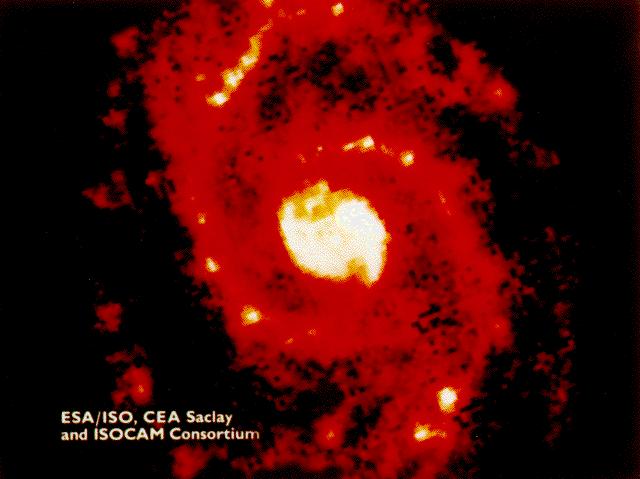

Other IR observatories

have since been placed in space. ISO, the Infrared Space Observatory, was operated

by ESA from November '95 until May '98. The instruments include an IR camera,

a spectrometer, and a polarimeter. The spectral range was 2.5 to 240 µm. This

is a colorized image of the Whirlpool Galaxy.

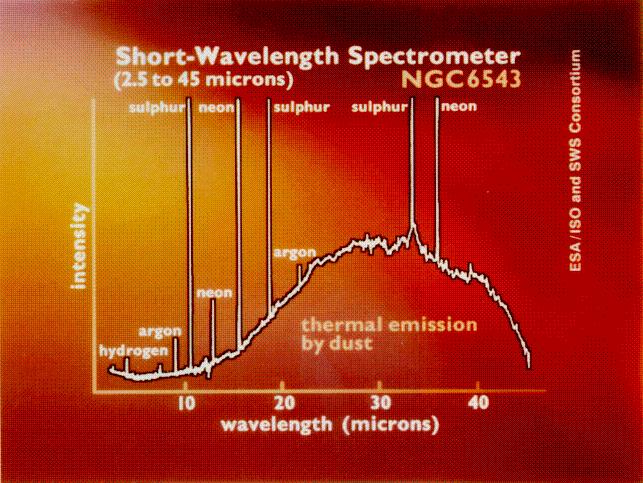

A short IR wavelength plot

of radiation received from NGC6543 shows peaks correlated with argon, neon,

hydrogen, and sulphur which occurs in the dust and gas nebula associated with

this, the Antennae galaxy.

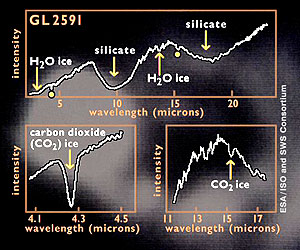

The star GL2591 is surrounded

by a dense cloud. Spectra in the Short Wave IR interval sampled by IS0's spectrometer

disclose water ice, carbon dioxide ice and silicate particles in the dust grains

within the enclosing material.

Infrared observations have

also yield new information about very distant galaxies in the outer reaches

of the Universe. This IR image shows, in the upper right, a glowingly-intense

large galaxy located far out into the early Universe. The radiation intensity

is believed to be related to energy released around a Black Hole (perhaps a

quasar).

Astronomical objects, in particular

galaxies and supernovae, emit the gamut of radiation across the spectrum. Galaxies

are usually strong emitters of microwave radiation, in particular in the radio

region. Radio waves are generated by excitation of neutral hydrogen. A good general

review of radio astronomy has been prepared by the Haystack group at MIT.

The specialized field of

radio astronomy utilizes large "dish" antennas to capture the long wavelength

radiation. One of the first radio wave monitors is the famed Arecibo site in

Puerto Rico, in which the parabolic receiver is embedded in a limestone sink

in the jungle. The dish, 305 meters (just over 1000 ft) wide, is fixed in orientation

and must use the rotation of the Earth to examine parts of the astronomical

heavens.

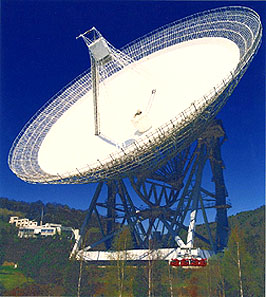

The largest movable telescope

in the world is the 100 meter radio antenna facility at Effelsberg in Germany.

It can both rotate and swing up and down.

Resolution of 00000000000celestial

targets from which radio waves emanate can be improved by developing a synthesized

aperture by means of electronically hooking together individual radio telescopes.

A major facility in the National Radio Astronomy Observatory group is the Y

shaped array of 27 radio telescopes, each 25 m (81 ft) in diameter, located

in the flats 70 miles west of Socorro, New Mexico. This creates an effective

resolution of 36 km (22 miles). This Very Large Array (VLA) mode uses principles

of Interferometry to process the signals from each telescope as a unit.

More background information

on radio interferometry can be found at these Australian

and Canadian

Web sites. In essence, the same signals are received almost simultaneously at

different receivers; when added together these may be out of phase and may cancel

out or reenforce at specific wavelengths; computer processing allows a new interference

signal to be produced. Radio telescopes separated

by hundreds and even thousands of kilometers can be tied together by electronic

wiring or radio signals to each other to produce an array called VLBI (Very

Long Baseline Interferometry). The effect of integrating the telescoope signals

is to increase the resolution significantly, so that smaller features in radio

objects can be discriminated. One of the major tasks

of radio astronomy was to survey the sky at 21 cm to pick up the distribution

of neutral hydrogen in the Milky Way and the halo around our galaxy. Here is

the result:

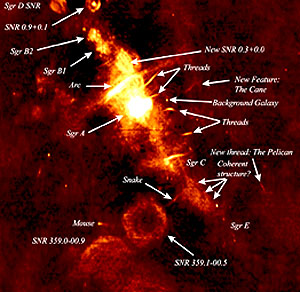

More details about the

central region of the Milky Way appear in this radio telescope image made at

90 cm.

Whole galaxies are imaged

at the 21 cm H wavelength. Here is M81:

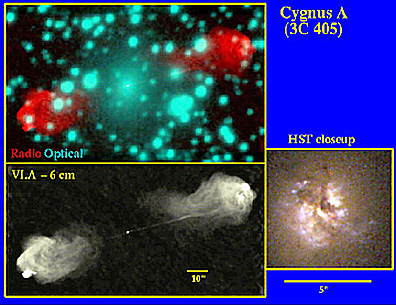

In the early days of radio

astronomy, many radio sources in deep space were discovered but when the same

region was examined by optical telescopy often no obvious galaxy or other stellar

body was found at first. Later observations at non-radio wavelengths have now

detected the astronomical feature, usually a galaxy (many galaxies are very strong

radio wave emitters). One of the best examples of powerful energy emitters in

which visible images do not detect any obvious sources is Cygnus A, from a galactic

center about 700 million light years away. Cygnus A is the strongest radio wave

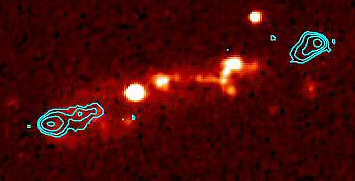

emitter in our part of the Universe. Consider these images:

In the above image, the

upper left shows a visible light image (star groupings in bright blue) but with

no obvious galactic shape; however as colorized in red are two distant lobes

representing radio wave signals associated with Cygnus A. The lower left image

is another radio wave rendition of signals received at 6 cm. The lower right,

made by HST, reveals some strong radiation coming from the central region of

Cygnus A. When that region is examined

through a ground-based x-ray telescope, again it shows below as an expanded

area of matter giving off high amounts of energy at short wavelengths. The inset

at the lower right is another radio wave image (note that there is a corresponding

area for each lobe in the x-ray image.

Here is a galaxy seen in

the Infrared, on which is superimposed the intensity contours associated with

two radio sources in the limbs that once seemed isolated from this distinct

galaxy.

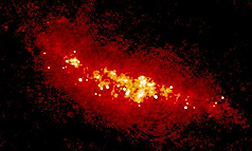

This next image shows an

L-Band image of the Starburst Galaxy; this was made at the Jodrell Bank Radio

Telescope Observatory near Manchester, England, one of the premier facilities

in the field. The signals were obtained from the MERLIN (Multi-Element Radio

Linked Interferometer Network).

A longer wavelength radio

image acquired by the MERLIN VLBI system shows the binary star pair SS433. Contour

lines show the extent of radio wave activity outside the central region occupied

by the star pair.

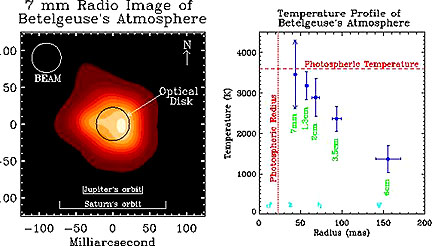

The Red Giant Star Betelguese

(see next page) has been imaged within the microwave region (outside the main

radio interval) at 7 mm. Under these conditions it was possible to measure a

temperature profile (right) in the expanded gas envelope (photosphere) around

the star.

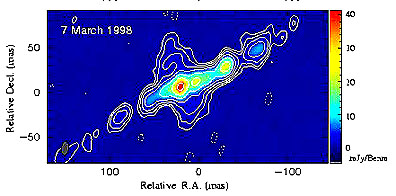

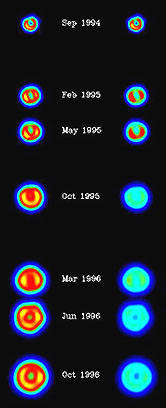

Supernovae (see page 20-6) are strong sources

of radio waves. They expand so rapidly that time lapse images taken months apart

can monitor their spread and the changes in shape of the radio wave field. Here

is such a sequence for Supernova SN1993J in the galaxy M81. The images on the

left were taken at 3.6 cm; those on the right at 6.0 cm.

The reader might have had

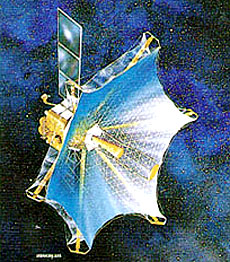

a thought during this review of radio astronomy: Why not put a radio telescope

in space? But, wouldn't the antenna be much larger than is commonly on satellites.

The answer is "No" if the VLBI concept (above) is employed. The Japanese Space

Program has developed and launched HALCA (Highly Advanced Laboratory for Communications

and Astronomy) in February 1997 as the kingpin in their VSOP (VLBI Space Observatory

Project) program. The radio satellite has a 25 m antenna and looks like this:

HALCA's orbit is elliptical,

with its perigee (closest approach) at 1000 km and apogee (farthest) at 20000

km. When coupled electronically with one or more radio telescopes on the ground,

the effective diameter of the joint system is greater than that of the Earth

itself (12755 km). This creates a very high resolution radio wave detector (in

some applications, 1000x better than the HST) when used in the Interferometer

mode. Although HALCA experienced some trouble in 1999, it did send back considerable

data and proved the concept of using multiple integrated radio receivers to

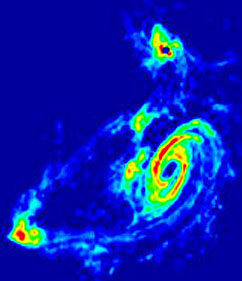

achieve exceptional resolution. Here are three images of quasars (see page 20-6) at considerable

distances from Earth that illustrate one of the ways in which HALCA data can

be displayed:

Plans to put other radio

telescopes in space are now active. Principles behind using multiple radio telescope

satellites, in formation flying, to increase resolution are examined on JPL's

Starlight

program site. Since we have introduced

the specialized technique of interferometry on this page, it is now appropriate

to revert back to imaging in the visible spectrum to mention the CHARA (Center

for High Resolution Astronomy; operated by Georgia State Univ. astronomers)

project which is now commencing operation at the famed Mt. Wilson Observatory

(in the mountains north of Los Angeles), shown here:

The large central observatory

dome houses the famed 100 inch Hooker telescope that Edwin Hubble used to track

down galaxies outside the Milky Way and to measure redshifts, laying the foundation

for the Big Bang model. In the above picture are several of the 6 auxiliary

optical telescopes tied to the main telescopes. Working in pairs, and later

in larger combinations, light from separate components of the array must be

combined and synchronized to produce interferometric images in which the waves

reenforce rather than cancel. This multiple system produces a baseline (at optimum,

1080 feet) that greatly increases the angular resolution of the central telescope,

thus providing images that are expected to exceed the Hubble Space Telescope

in sharpness. To get the signals from two or more telescopes into coincidence

(the light arrives at any two pairs at slightly different times), one beam is

sent through an optical pipe that contain movable mirrors mounted on rails (the

"delay line"). The mirror(s) are moved until the extra distance traveled by

light to the second telescope (relative to the first) is just compensated enough

(equalized) to bring the two signals into phase. This delicate adjustment is

made through a computer program that controls pathway adjustments. With this examination of

space observatories that collect data over different parts of the spectrum,

we now return to the exposition of aspects of Cosmology by looking at the origin

and evolution of individual stars.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()