Models

for the Origin of Planetary Systems

This "crash course" on Cosmology

closes with the following brief synopsis on the methods and results of astronomers'

search for other planetary systems and consideration of the origin of our own

Solar System, plus a quick look at several of the latest, provocative, and especially

exciting theories (or brash speculations) on the presence of other intellectual

beings in our Universe that might be "out there".

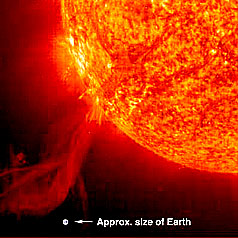

Two hallmarks in particular

distinguish planets from stars they orbit: First, they usually show marked differences

in composition, being either gas balls with other elements besides hydrogen

that have rocky cores or they are dominantly rock with many elements making

up usually silicate minerals. Second, they are significantly smaller in diameter

(hence volume) than their parent star. This SOHO image of a part of the Sun,

with a solar prominence, illustrates this size difference, as displayed by adding

a drawn sphere the size of the Earth to allow comparison:

This huge size difference

between the Earth and its normal G star Sun is humbling in its stark truth.

The great disparity in size also makes it clear how difficult it will be to

find Earth-sized planets around nearby stars - and even more of a technology

challenge as astronomers entertain hopes of finding stars elsewhere in the Milky

Way galaxy and galaxies beyond.

It is natural for humans to

wonder if there is life elsewhere in the Milky Way, and by implication in other

galaxies. The starting point in searching for life is to prove the existence of

other planets and inventory their characteristics. In the last decade the hunt

for planetary systems has intensified. The first extrasolar planet was found in

1995 orbiting the star 51 Pegasi. As of this writing (June 2002), planetary bodies

have now been detected in at least 67 other stellar (~solar) systems; as of November

2002 more than 100 individual planets have been associated with these systems.

Analysis of one such system - Upsilon Andromedae -indicates it to have 3 planets

(a second triple star system was recently discovered); 8 other stars have 2 planets.

The U. Andromedae system consists of Giant (probably gas-ball) planets (much smaller

ones presently cannot be detected), all within orbits occupied by the four small

terrestrial planets in our Solar System:

So far, no planet has actually

been seen, being too small to be detected optically using present day technology,

but the existence of such low-luminosity bodies can be deduced from their interactions

with their parent star. Almost all discovered so far are large - Jupiter-sized

or greater - and are gas balls. Several are extremely close to their star (at

distances less than Mercury's orbit). Many planets have much more elliptical orbits

than those moving in the Solar System. It is hypothesized that most planetary

systems will consist of multiple planets but the smaller ones are presently still

invisible to us.

A high point in the current

search for planets occurred on June, 2002 when several groups of astronomers

announced jointly the discovery of up to 20 new planets - including at least

two of Jupiter size - in the Milky Way galaxy, whose stellar parents reside

at distances ranging from 10.5 to 202 light years from Earth. The closest in

has been provisionally named Epsilon Eridani b (its star is the one actually

cited in the Star Trek series as the location around which Mr. Spock's

home planet, Vulcan, was orbiting). The rate of planet discovery seems to be

accelerating. With it is the growing belief by cosmologists that planets could

well exist in the billions, i.e., they are the inevitable result of processes

that take place when most stars are born. Thus, planets may well turn out to

be the norm - the expected, and perhaps the most significant products

of nebular collapse in stellar evolution. The proponents of SETI (Search for

Extraterrestrial Life; seeking primarily radio signals that have non-random

character [perhaps some form of mathematical organization]) have been galvanized

by these recent discoveries. (The writer is convinced that it is only a matter

of time - probably during the 21st Century - until contact with other

intelligent beings is achieved.) We will return to the SETI idea near the bottom

of this page.

Current search for extra-solar

planets is restricted to the Milky Way and galaxies close enough to Earth for

an individual star to be resolved to the extent that changes in its motion can

be measured. Gravitation attractions from orbiting planetary bodies cause the

central star to wobble. This is the basis for the three methods currently being

used to detect anomalies in a star's behavior that lead to the inference of one

or more orbiting bodies.

The method that has so

far been the most successful in locating (invisible) planetary bodies is called

the radial-velocity technique. A component of a star's wobble will potentially

lie in the direction on-line to the Earth as an observatory. This to and fro

(forward-backward) motion causes slight variations in the apparent velocity

of light. That, in turn, gives rise to small but measurable Doppler shifts in

the frequencies of light radiation from specific excited elements, as expressed

by lateral displacements of their spectral lines. From the wobble magnitude

and period, the approximate orbit and mass of its presumed cause - the orbiting

planet - can be calculated. This method is sensitive to wobble velocities as

low as 2 meters per second. (Jupiter, for example, causes a wobble velocity

of 12.5 m/sec imposed on light radial from the Sun. Generally, this method,

applied to nearby stars, will detect mainly large planets close to their star

but in March of 2000, two planets about Saturn-size (1/3rd the mass of Jupiter)

were found.

The second method, astrometry,

also relies on wobble but depends on measuring side to side displacements by

direct observation through periodic sightings. This determination of relative

shifts can be done on photographic plates taken of part of the sky at different

times, commonly using the same telescope. But, considerable improvement shift

resolution results when two telescopes are positioned apart and joined electronically.

This permits application of interferometry such that the two telescopes act

as though they were one large one. Resolution as sharp as 20 millionths of an

arc second (an arc second is 1/3600ths of an arc degree on the sky hemisphere

[0° at the sealevel horizon; 90° at the zenith near Polaris in the northern

hemisphere]). The Keck interferometric telescope in Hawaii will soon be operational.

This should facilitate detection of even smaller planets in nearby space or

large planets in stars 10s of light years away.

As we have seen with the

HST images in this Section, resolution (and clarity) is significantly improved

by operating a telescope in space, above the distorting atmosphere. The use

of two telescopes mounted on a single boom but separated by meters allows the

interferometric method to work on space-quality imagery. SIM (Space Interferometry

Mission) is a NASA probe slated to fly during or after 2005. This will lead

to a millionth of an arcsecond resolution, capable of inferring the presence

of planets just larger than Earth-size or of large planets with far out orbits.

A third method is called transit

photometry. When a planet's orbit takes it on a path where it passes across

the face of the star under observation, the body will block out a small amount

of radiation (usually visible light) for the period of transit. Sensitive detectors

can note the slight diminution (up to about 2%). To distinguish this from a "transient

event" of other origin, the astronomer needs to establish some regularity (reproducible

at fixed intervals) of the drop in radiation, which will depend on the nature

of the orbit (ellipticity; distance, etc.) Depending on planet size and proximity,

the drop in stellar luminosity will be a few percent or less (an accurate determination

helps to establish the planet's actual size). Such an effect was first noted in

1999 when a giant planet (earlier found by the radial-velocity method) passed

in front of a star (HD 209468) whose light intensity underwent a drop of 1.5%.

In a June, 2002 meeting, two other groups using telescopes in Chile have reported

3 and 13 possible transit detections, but these observations have yet to be confirmed

independently.

This promising transit approach

will be used in the recently approved Kepler mission (launch in 2006) in which

a space telescope would be pointed on the same areas in the stellar field for

up to four years, integrating brightness measurements to single out variations

as small as 0.01% (capable of detecting Earth mass-sized planets). Up to 100,000

stars can be conveniently monitored over time and individuals with multiple planets

should reveal the relative number of stars that possess planetary systems. Two

other non-U.S. missions, COROT and Eddington, are in the planning

stage. Thus, as detectors improve and instruments become spaceborne above the

atmosphere, sometime in the next 10-20 years Earth-sized planets should become

detectable by measuring drops in stellar light curves owing to transits of large

planet(s) across their parent star.

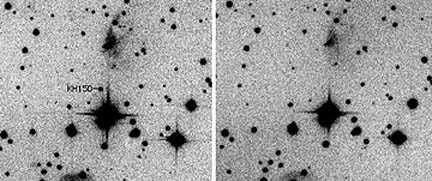

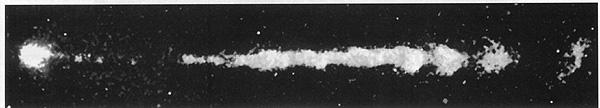

A fourth method has just

had its first success in June of 2002. Examine this pair of images:

This is called the eclipsed

or "winking" star method. In the left image (a photo negative), a Milky Way

star KH 15D (2400 l.y. away; about the size of the Sun) is visible behind a

much closer (or larger) star. In the right image it is totally absent, a condition

lasting for about 18 days, and then it reappears. This on-off cycle occurs every

48 days. The eclipsing body could not be another star nor is it likely to be

a huge (star-size) planet. The interpretation is that there is a cloud of asteroids

and dust in a smeared-out clump orbiting KH 15D which block the starlight when

a clump passes across the parent star; speculation considers that there may

already be one or more planets formed from this debris. There may actually be

two clumps (symmetrical pairing) at opposite positions in a single orbit; this

has yet to be confirmed.

A fifth method is still

in the experimental planning stage. The Terrestrial Planet Finder program at

Princeton University is developing a special type of "cats-eye" mirror that

will greatly reduce the effect of the luminous parent star. When this technology

is deemed ready, they hope to persuade NASA or some other agency to use mirrors

on several telescope-bearing satellite flying in formation and spaced to utilize

the principle of interferometry to improve resolution and to detect small planetary

objects.

The ultimate dream is to

directly visualize individual planets. This may be possible using several HST

type spacecraft flying in formation ("clusters") with separations of a few hundred

meters to hundreds of kilometers. In one mode, data will be combined using interferometric

principles. Light from the central star can be blocked out by specialized image

processing, leaving a residue of low luminosity orbiting bodies detectable by

resolution- and radiation-sensitive interferometry. Both NASA and ESA each have

in the planning stage such a mission (called The Terrestrial Planet Finder

and Darwin, respectively).

Statistically speaking, the

number of such planetary systems should extend into the millions within individual

galaxies and the billions when the whole Universe is considered. It would logically

be likely therefore that non- or weakly-self-luminous bodies, i.e. planets, are

the norm orbiting around a central star for at least some of the size classes

on the Main Sequence of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. As such stars proceed

through their developmental stages (before they leave the Main Sequence), planets

seem the inevitable outcome of the formational processes involved in star-making.

Two scientists, C. Lineweaver

and D. Grether of the University of New South Wales in Australia, have recently

published a study that relies on reasonable probabilities to estimate the number

of planets just in the Milky Way. They argue that, of the approximately 300 billion

stars they calculate to be the total population of the M.W, about 10% or 30 billion

consist of stars similar to our Sun and most likely to have favorable conditions

for planet formation. Assuming that, of these, at least 10% will produce giant,

Jupiter-like planets. Such large planets would almost certainly be accompanied

by smaller ones formed out of the materials (they call "space junk") associate

with the parent star. These giants help in the collection process that leads to

smaller companions. But, more importantly, the giants serve as the principal attractors

that gravitationally pull comets and asteroids into them (remember the Shoemaker-Levy

event discussed in Section 19) and thus function as "protectors" of the small

planets by minimizing the impacts these receive.

For a while, astronomers

assumed that most stars with planets would be relatively small - Sun-sized to

perhaps 10 solar masses. These stars last for billions of years and thus favor

the eventuality of life if planets developed during the stellar formation process.

Now, several notably larger stars in the Milky Way have been found to have large

planets. So, planetary formation is a function of process primarily and may

have little to do with how long its star can survive. But the really big stars,

even with planets, would burn their fuel and destruct long before evolution

would likely foster even primitive organic matter.

While astronomers exercise

caution about conclusions that specify the number of earthlike planets to be expected

from their estimation procedure, they do propose that that number should be in

the millions. Whether such planets also harbor life is much harder to pin down

numerically but their statistical approach suggests that a significant fraction

of the earthlike planets would possess the proper conditions. How much of that

is intelligent life is still guesswork. The current sample of 1 (us!) is the only

data point. But if the reality is actually a much larger number, then, purely

from statistical logic, we should expect that some of these intelligent civilizations

should be more advanced than ours. Why we have yet to "hear" from them remains

uncertain (but now SETI improves the chances for this) unless there is some fundamental

reason that makes space travel, even from nearby stars, very difficult.

Now, let's turn to consideration

of the ways in which planets form. The paradigm summarizing the processes involved

in the formation of the Sun and its planets probably applies (with variations)

to other planetary systems in general. The first realistic notion of how planets

form was proposed by Pierre Laplace in the 18th Century. In its modern version,

both stars and their planets are considered to evolve from individual clots or

densifications within larger nebular (cloudlike) concentrations dominantly of

molecular hydrogen mixed with some silicate dust particles that spread throughout

the protogalaxies and persisted even as these galaxies matured. In younger stars,

much of the hydrogen and the heavier elements are derived from nova/supernova

explosions that have dispersed them as interstellar matter that then may initiate

clouds or mix with earlier clouds. Such nebulae are rather common throughout the

Universe, as is continually being confirmed by new observations with the Hubble

Space Telescope.

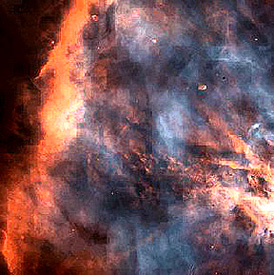

One of the best studied

and, in itself spectacular, is the Orion Nebula, seen here:

Below are three views of

nebular materials associated with the famed Eagle Nebula: Top = full display

of the M16 (Eagle) nebula (note the dark dust areas; the white dots are stars

lying outside this nebula); Center = part of Eagle nebula, showing top of the

Horsehead pillar of dust and gases from which stars and planets may eventually

evolve (a few stars already being evident), made by combining three film exposures

through the Kuevn Telescope at the European Southern Observatory ; Bottom =

details of the temperature variations in the dust making up the solid particulates

in the Eagle nebula as imaged by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Infrared

Space Observatory (ISO) at two thermal infrared wavelengths, in which red is

hot and blue is cooler (about - 100° C):

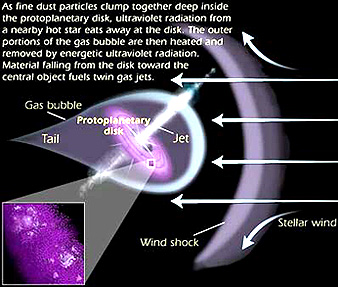

As individual stars start

to develop within these gas and dust clouds, in many instances that dust will

organize into a protoplanetary disk (see third figure below). The NICMOS infrared

camera on the Hubble Space Telescope has observed a prime example of this stage,

in which the glowing gases moving into the central region where a protostar

is building up are cut by a band of light-absorbing dust that is most likely

disk shaped (can't be verified from the side view in this image):

An Earth-based telescope

has captured this view of a nearby star (nicknamed the "flying Saucer"), again

with a girdling disk of dust (and an as yet unexplained anomaly in that the

upper half of the image is redder than the bluer lower half):

Examination of these gas

and dust clouds by HST has led to the discovery of small clumps or knots of

organized gas-dust enrichment within the protoplanetary disks called Propylids

found in the neighborhood of a parent star. This may be a more advanced

stage of concentration that results in a new star with an envelope of gas-dust

suited to accretion that produces planets. Three such propylids are evident

in this image of the nebula associated with the Orion galactic cluster (go back

to the top image in the three above to try to spot for a conspicuous propylid).

Other individuals, at least

one possibly as recently formed as 100,000 years ago, found during the Orion

study (see page 20-2 for

a view of the entire young nebula in the Orion group) look like this in closer

views:

Propylids are vulnerable

to being destroyed by UV radiation from massive, young nearby stars. It is surprising

therefore that many propylids (some shown below) have survived in the Carina

Nebula, which has numerous UV-emitting stars. Other factors must be involved

Development of planetary

cores, from which full larger planets then form, is a race against time. Examine

this model:

As the gas and dust cloud

forms, particles of solids begin to clump. However, the cloud is threatened

by stellar winds and UV radiation from the parent star that remove most gas

and some dust. Evidence suggests that most propylids are blown away before a

planet grows large enough to survive, implying that the planet formation process

may be less efficient and common than had been thought during the last decade.

If the planetary cores do build up fast enough, they will survive the expulsion

of the bulk of the gas/dust. This phase of planet formation occurs typically

in a time frame of just 100,000 years or so; it is estimated that 90% of such

clouds are dissipated before significant planetary cores can form. Planet accretion

leading to survival is estimated to take up to 10,000,000 years.

Most galaxies

began during the first half of the Universe and contained a large number of

massive stars that formed early in galactic histories. These galaxies have continuously

been evolving through the eons as supernovae synthesized elements (see page 20-7) and dispersed them,

and new, mostly Main Sequence stars, chemically enriched with elements of higher

atomic number, have continued to form well into younger times up through the

present. The smaller stars have lasted much longer and are probably the preferred

sizes suited to planetary formation and survival. Even today stars are developing

from the gases contained in remaining nebular material, so new planets could

still be forming. What is not yet known is the percentage of stars in a galaxy

that actually have planetary systems. The low number so far found does not necessarily

represent an indication of sparsity, since planets are so small and most low

in luminosity (mainly from reflected light) relative to their parent star that

present direct observations will produce extremely low numbers, thus subjecting

our current conclusions that planets may be rare to a misleading bias.

Some models of star formation from gaseous nebula suggest that a fraction of

the gases, dust, and free molecules is trapped in orbit without infalling to

the central star and can organize in planets of various sizes, distances, and

composition in a manner similar to our Solar System. If a valid argument, this

says that planetary bodies are commonplace throughout the Universe.

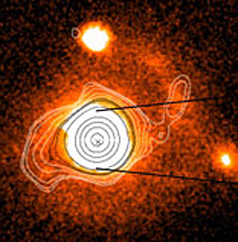

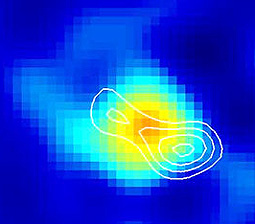

A telescope observation, reported

in April, 1998, records the sighting (through the Keck II telescope on Mauna Kea,

Hawaii) of what is interpreted to be another "solar" system around star HR 4796

(about 220 light years away). This image (at a resolution in which individual

pixels stand out), taken in the IR, shows this central star (yellow white) surrounded

by a lenticular (in an oblique view), flattened disk of gases and solid matter

(glowing hot [reds] in the infrared):

The diameter of the lens is

about 200 A.U. No evidence of individual planets can be made out but the discoverers

judge this feature, which has caused quite a stir of interest, to be an emerging

planetary system in a "young adult" stage of development. It will certainly be

a target for more detailed HST observations.

More recently, the Hubble

Space Telescope has imaged star HR4796A, in our galaxy, which shows both a disk

and irregular dust and gas clouds. This disk is interpreted to be in a more

advanced (mature) stage of development than the protodisks shown above. Although

not discernible, there may be planets already in the evolving gas/dust cloud

which is made visible by the star's light.

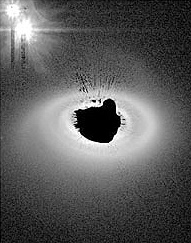

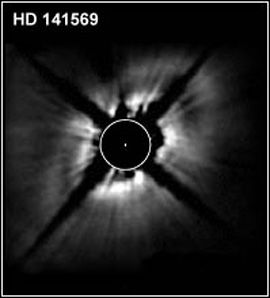

Star HD1569A, in the Milky

Way galaxy, also shows wide disk of dust glowing from reflected light emanating

from the black objects (their light blocked out by the coronagraph on Hubble's

High Resolution Camera) which astronomers have identified as a triple star complex.

This disk may be in an earlier stage of organization than shown in the preceding

image, but it too may eventually lead to planets.

Theory indicates that, in

the earlier stages of planetary formation, some number of broad rings should develop

at various distances around the central star. One or more of these would appear

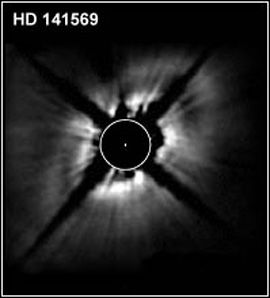

as torus like glowing collections of dust and gases. At least two stars with this

feature were imaged by HST and reported in January of 1999. Here is one of the

star-ring systems:

Visible is a bright ring at

some considerable distance out from the tiny parent star (white dot) and a more

diffuse, darker mass extending beyond, both features occupying a flattened disc.

In this instance, there are no rings close in (analogous to the regions occupied

by the inner planets of the Solar System). The white circle is added by the astronomers

to mark a boundary; the broad black cross (X) is an optical artifact. This star

is about 350 light years from Earth.

A recent image, made from

data detected at 1.3 mm by a French radio telescope, may have caught the formation

of two large clots of matter likely to eventually contract into giant planets.

These occur in the ring around the central star Vega, 25 light years away (in

the Constellation Lyra). Here is an image based on observations made by D. Wilner

and D. Aguilar of Harvard's Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. (Note: this

image has been enhanced artificially as an artist's rendition.)

Drs. C. Chen and M. Jura,

Univ. of California-Berkeley have detected (monitoring infrared radiation) a

ring of dust which seems to contain asteroid-like bodies around Zeta Leporis,

a star some 70 l.y. from Earth. The ring is much closer (~2.5 A.U.) to its parent

star than the distances found for other recently observed or inferred planetary

bodies around stars. They propose this ring to be the precursor of eventual

formation, by collision of asteroidal bodies, of rocky planets analogous to

those of the Solar System. These bodies, form from smaller particles (dust)

condensed from the gas-particle cloud associated with the forming star. Much

of that dust can move inward towards the star by a process called Poynting-Robertson

drag. This is caused by radiation from the parent star being absorbed and re-radiated

differentially, leading to a Doppler effect (here, the energy of emission in

the direction of dust motion is at shorter wavelengths [more energetic] and

thus by retro-action slows the particles) that promotes drift of the dust towards

the star.

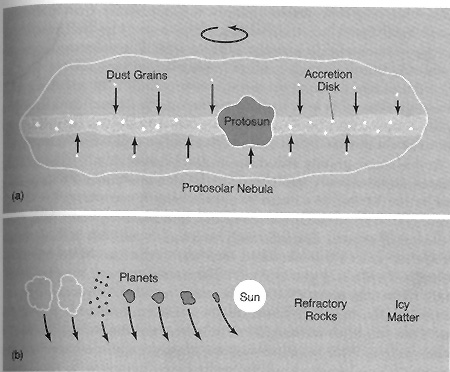

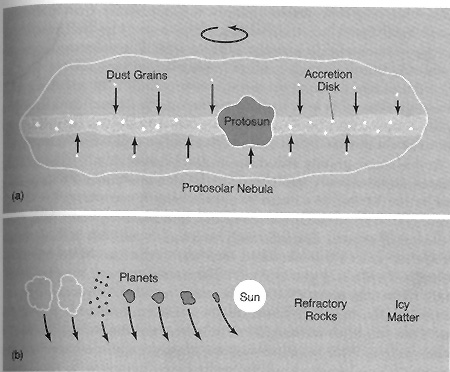

The following is a generally

accepted model (called "core accretion") for establishing a planetary system:

A nebula is subject to gravitational irregularities and other perturbations that

cause free-fall collapse to numerous clots around which surrounding gases and

particulates usually adopt a disklike form. The influence of gravity, which builds

up progressively as clots enlarge, is the prime driving force promoting both planet

and star (Sun) formation. In some instances, shock waves from a supernova can

cause interstellar matter to initiate collapse and compress into protostars and

debris orbiting them. Matter is also redistributed along magnetic field lines

by magnetohydrodyamic processes. The main phases of planetary formation extend

over about 10-20 x 106 years but it may require up to 108

years to progress from the early infall to the late T Tauri stage of a protostar's

development. While a particular clot is organizing, the materials tend to redistribute

such that hydrogen and much of the lighter elements flow towards a growing center

to accumulate in a gravitationally balanced sphere, the star. Under one set of

conditions, instabilities lead to a double (binary) star pair. As protostars form,

the rotating gases and dust particles collect in a spinning disk around each center

and eventually organize by accretion into planets. The same process, with variants,

works at single stars.

If our Solar System is

the norm, inner planets should be rocky, with thin or absent atmosphere (lost

from insufficient gravitational ability to retain the gases or by being swept

away by the solar wind). Outer planets should have rocky cores and be less susceptible

to loss of gases, so that their increased mass serves to gather in still more

gases. However, the discovery that giant planets can lie quite close to their

parent stars places this assumption of size distribution with distance into

question.

Two recent hypotheses are

adding new twists to the above concepts. First, in addition to or in place of

core accretion, another mechanism called "disc instability" may play an important,

perhaps key role, in planetary inception. This is related to gravitational irregularities

that can cause rather rapid accumulation of materials in the proto-planetary disc.

Earlier-formed planets can contribute to setting up further instabilities. A second

idea holds that planets can move inward or even outward in a form of migration

or "wandering" so that their orbits change both in relative distance to their

parent star(s) and in eccentricity.

But for the present, astronomers

continue to build and refine their models on the much easier-to-make observations

at the astronomically short distances within the Solar System. Like other stars,

the Sun (whose diameter is 1,392,000 km [870,000 miles]) is an end-product of

gravitationally-driven condensation and collapse of hydrogen/helium gases and

associated matter (both solid and gaseous) consisting of other elements and compounds

that once made up a diffuse (density ~ 1000 atoms/cc) nebula. Probably many stars

were generated in the timeframe of a few hundred million years from this particular

"cloud".

The protosun built up from

centripetal, gravity-induced infall of nebular substances towards one of the

concentration centers in the nebula. The bulk of the gases enters the resulting

star itself along with much of the other materials, leaving an enveloping residue

of matter enriched in Si, C, O (and H), N, Ca, Mg, Fe, Ti, Al, Na, K, and S

(most organized into compounds, particularly silicates, that can be sampled

by recovery of iron and stony meteorites - representing fragments of comets

and broken protoplanets that are swept up onto Earth). This material, bound

by gravity to the Sun but free to move inertially in encircling orbits, remained

distributed in the space making up the Solar System. This system of particles

rather rapidly organized into a disc-like shape whose present radius is about

100 A.U. (Astronomical Unit, defined as the average distance [149.6 x 106

km, or about 93 million miles] between the centers of the Earth and Sun;

solar light takes about 8 and a half minutes to travel that distance; Pluto,

lies 39.5 A.U. from the Sun whose gravitational influence is exerted well beyond).

The disc rotated slowly (counterclockwise relative to a viewpoint above the

north celestial pole [which passes through Polaris, the North Star]), its motion

influenced by external gravitational effects from nearby stars.

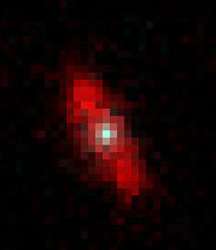

As this rotation got underway,

and thereafter, the stellar (solar) magnetic field churned up the dust and gases

(descriptively compared to the action of an "eggbeater" in a thin batter) causing

them to collect into clots much smaller than the Sun that underwent various

degrees of condensation. This field also expels and guides this material into

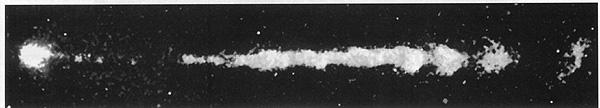

jets that carry matter out to great distances, as seen here in this Hubble Space

Telescope view of a jet ejecting from another star in our galaxy:

Both jets and irregular

nebular patches (e.g., the Horsehead and Eagle nebulas shown above) contain

not only gases but significant amounts of dust. The dust is very small and consists

of three types: 1) core-mantle elliptical particles, typically 0.3 to 0.5 microns

in long dimension, with a silicate interior coated by icy forms of gases; 2)

carbonaceous particles (~0.005 microns), and 3) open frothy clots called PAH

dust (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) (~0.002 microns). Shock waves and radiation

can strip off the ice mantle leaving grains that are incorporated into coalescing

bodies that form the prototypes which accrete into the planetesimals from which

asteroids or planets then build up. Ultraviolet radiation can modify the organics

into more complex molecular forms. In this way, organic molecules are introduced

from space onto planetary surface and, if conditions are right, can eventually

serve as viable ingredients for the inception of living things (see below).

The possible role of shock

waves in planetary formation is now the subject of considerable study. Evidence

for a shock wave that develops as material falls towards a nearby protostar

against its remaining gas/dust cloud has been observed at L1157, in which the

present cloud is about 20 times the solar system diameter. As this cloud proceeds

to infall into the newborn star as it organizes into a disk, it produces shock

waves that may clump dust together, as described in the next paragraph. Here

is this cloud:

For the Solar System, shock

waves and intense radiation acted on the dust such that some of it melted into

tiny droplets which chill into chondrules. These spherical bodies then

were caught up with remaining dust to produce the primitive small solid bodies

(fluffy "rockballs") that populated much of the heliosphere surrounding the

Sun. We see samples of these bodies today as meteorites. Most infallen

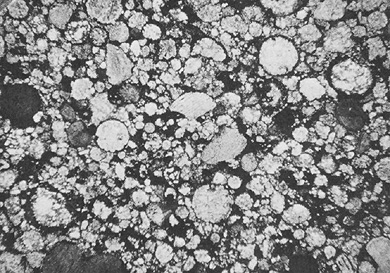

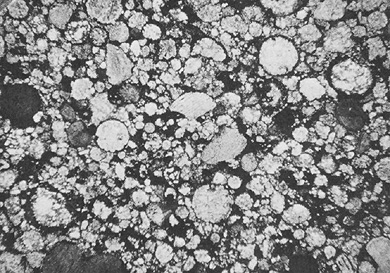

meteorites are ordinary chondrites that, in thin section, appear much like this

sample from the Tieschitz meteorite:

The most primitive meteorites,

called carbonaceous chondrites, are enriched in carbon and contain water. Other

meteorites are iron-rich (some with > 90% metallic iron), and may have once

been the interiors of planetary bodies since disrupted. The chondrules themselves

generally show a very limited size range, suggesting that ones larger than these

fell back into the Sun through gravitational pull whereas smaller ones were

swept away into interstellar space through expulsion by shock waves and solar

wind.

Magnetically-driven eddies

within the gas/dust cloud helped to impart additional angular momentum to the

larger condensed rotating objects beyond the spherical Sun (which possesses

only 0.55% of this momentum even though it contains 99.87% of the total mass

of the system). These objects now remain in orbits around the Sun in positions

that remain stable because of the counterbalance between centrifugal forces

related to angular momentum and inward-directed gravitational pull from the

Sun.

Planets appear to form simultaneously

with the star around which they associate in well-defined orbits. As the formative

process operated, local instabilities in the nebula tied to the Sun caused the

chondrule-laden rockballs within turbulent zones to cluster and further aggregate

into objects ranging from meter-size up to planetesimal dimensions (tens

to a few hundred kilometers, typified [perhaps coincidentally] by asteroid proportions).

From J. Silk, The Big Bang,

2nd Ed., © 1989. Reproduced by permission of W.H. Freeman Co., New York

During this growth stage,

smaller planetesimals tended to break apart repeatedly from mutual collisions

while larger ones survived by attracting most of the smaller ones gravitationally,

growing by accretion as new matter impacted on their surfaces. Once started,

"runaway" growth ensues so that many planetesimals combine into bodies that

eventually enlarge into fullblown planets. The bulk of the matter beyond the

Sun was swept into the planets and their satellites, although some remains in

comets and cosmic dust. Mercury, and some Outer Planet satellites are preserved

remnants of this later stage in planetary growth, as indicated by their heavily

cratered surfaces that were never destroyed by subsequent processes such as

erosion. In contrast, the Moon appears to have built up by re-aggregation of

debris hurled into space as ejecta from a giant impact on Earth soon after our

planet formed; once collected into a sphere (which probably melted), the lunar

surface continued to be bombarded with its own remnants as well as asteroids

and other space debris. Its oldest craters are hundred of millions of years

younger than the time at which the debris reassembled, melted and formed the

lunar sphere; at least some of its larger basins are somewhat older.

As mentioned above, in our

Solar System, the four inner planets (the Terrestrial Group) are largely

rocky (silicates, oxides, and some free iron; three with atmospheres) and the

outer four (Giant Group) are mostly gases with possible rock cores. These

Giants developed large enough cores to attract and capture significant fractions

of the nebular gases dispersed in the accretion disk.

Analysis of argon, nitrogen,

and other gases in Jupiter indicates their amounts are such that this Giant

must have formed under very cold conditions; if further work bears this out,

Solar System scientists may adopt, as one plausible explanation, an origin of

Jupiter (and perhaps the other Giants) at much greater initial distances from

the Sun with these having since moved significantly closer through orbital contraction

or decay. The ninth planet, Pluto, the smallest and, at times, farthest out

(its elliptical orbit periodically brings it within that of Neptune), appears

to be made up of rock and ice and may be a captured satellite of Neptune.

Theoreticians differ as

to the exact methods and sequence in which the planets accumulated after the

condensation and planetesimal phases. Timing is a critical aspect of the formation

history. One version - the equilibrium condensation model - considers

condensation to happen early and quickly, in a few million years, with the observed

sunward zoning of higher temperature minerals and greater densities in the rocky

inner planets both being consequences of the increasing temperature profile

inward across the solar nebula. Accretion was stretched out over 100 million

years or so. The heterogeneous accretion model holds condensation and

buildup of planetesimals to proceed simultaneously over a few tens of millions

of years. Neither model adequately explains the fact that both high and low

temperature minerals aggregate together in the inner planets to provide materials

capable of generating the atmospheric gases released from these planets. The

models also do not fully account for the strong preferential concentration of

iron and other siderophile ("iron-loving") elements in the inner, terrestrial

planets. One solution is to add (by impact) low temperature material to the

growing protoplanets carried in along eccentric orbits from asteroidal and giant

planet regions. This material is then homogenized during the total melting assumed

for each inner planet early in its evolution (this melting is the consequence

of heat deposited from accretionary impacts, from gravitational contraction,

and from release during radioactive decay). As cooling ensues, materials are

redistributed during the general differentiation that carries heavy metals and

compounds towards the center and allows light materials to "float" upwards towards

the surface.

From an anthropocentric

outlook, the importance in understanding planetary formation mechanisms and

history is the assumption (not a clearcut fact) that planets possessing certain

appropriate conditions are the harbors of life. Life, it is believed by Earth

dwellers who can think, may well be the most complex and advanced feature in

the Universe, based on the presumption that it has (through us) evolved into

a state resulting in lifeforms that perceive beyond sensing, analyze through

reason, and evaluate most other aspects of known existence. Life, under this

viewpoint, is the quintessential achievement in the evolution of the Universe

to date. Whether life on Earth stands at the pinnacle, or somewhere below, has

yet to be established - statistically, it is most likely that somewhere in the

Universe even more highly developed living creatures, with superior intellects,

exist today or have in the past. (The ideas just enunciated are closely associated

with the modern doctrine called humanism.

Thus, the capstone of this

Section on Cosmology must surely be a consideration of the most provocative

and fascinating Quest in the history of life - the attempts to determine whether

life - and specifically intelligent life - exists elsewhere in the Universe.

Philosophically, many on Earth hope that we are unique - thinking beings that

are the pinnacle and teleological goal of a Creator's act. Scientifically, most

cosmologists, biologists, etc. are coming around to the firm conviction that

life does indeed exist elsewhere - throughout the Universe. This is a logical

conclusion, since a huge Universe with just one tiny inhabited body on which

conscious creatures exist strikes most scientists, and a growing number of philosophers,

as extremely unlikely, and, from a practical sense, even a foolish, wasteful

action by any Creator (this viewpoint is touched upon again later on this page).

One of the prime motivations

that has stemmed from space exploration continues to the the Search for

ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence (SETI) - which is a much

higher goal than simply seeking evidence that lower levels of life exist elsewhere.

This has so far been something of an ad hoc effort by a small number

of dedicated astronomers who have had limited support from private sources (the

movie "Contact" captures the essence of this effort). Now, NASA and other large

organizations have become involved and a more concerted and systematic hunt

for advanced life forms is being funded.

The ways in which SETI

now seeks evidence for intelligent life are diverse and innovative. This is

a very daunting and intriguing subject that could warrant considerable coverage

space on this page but reluctantly must be confined to a synopsis of a few key

ideas. However, we choose to guide you to several sites on the Internet for

many of the omitted details. The starting point is the SETI

site itself. The SETI Institute is currently being directed by Dr. Frank

Drake, the originator of what is now known as Drake's Equation. Here are three

Internet sites that discuss in some depth that equation: (1), (2),

and (3).

For the record, we now

state the Drake Equation (in its "dimensional analysis" format) and add some

comments on values used in its terms (you can choose your own set of value in

(2) above to see how changes affect the outcome):

N = R fp

ne fl fi fc L

where,

N = the number of communicating

civilizations in the Universe.

R = the rate of formation

of stars of types around which planets can form

ne = the number

of Earth-like bodies in the planetary system

fl = the fraction

of planets with life

fi = the fraction

with intelligent life

fc = the fraction

that has developed interstellar communication systems

L = the lifetime (span)

of civilizations (up to extinction)

Of course, none of these

parameters has yet been fixed with reasonably certainty, so that many values

(and ranges thereof) have been proposed. One common set (but still provisional)

has R = 10; fp = 0.5; ne = 0.2; fl = 0.2; fi

= 0.2; fc = 0.2, and L = 50000 (source: Article "Why ET hasn't Called",

by M. Shermer; Scientific American, August 2002). For our galaxy, this

set of values give N = 400 civilizations.

Each of these term inputs

is easily challenged. For fp, any number chosen would depend on such

variables as the total number of stars in a galaxy and the type of star suited

to planetary formation (usually limited to G and K types) and its percentage

of the total population. Recent estimates center around 10% (factor = 0.1).

At the 2001 Annual Meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Dr. J. Bally

of the Univ. of Colorado presented an argument which concludes that only about

5% of the stars in the Universe are capable of producing (surviving) planetary

systems. Massive stars will blow away the gas and dust needed for planets to

form. Binary or ternary star systems, which are the most common arrangement,

also are unfavorable for planetary growth, especially since one of the pair

or trio is likely to be a Giant, and matter is collected as jets owing to attraction.

He concludes that planets need to form soon after a star is born in order to

have a reasonable chance for survival.

Plausible arguments can be

made for values/ranges of each of the others. For example, fl will

be sensitive to such related variables as the presence and importance of water,

the nature of the evolved atmosphere, and the time needed for higher order life

forms to evolve (relative to planet age; rate can vary as these others assume

values other than that of our Earth). The possibility of non-carbon-based life

forms must be factored in. In Shermer's article, he calls attention to the great

uncertainty of L, the time over which any intelligences will persist before extinction.

Pessimists feel that this number can be small. For Earth, civilized life is only

about 5000 years old (based on the time at which agriculture and earliest urbanization

become practiced). With the advent of the atomic bomb, these doomsayers consider

that total mass destruction may be likely. On the other hand, one can conceptualize

human society as overcoming its self-destruction tendencies and lasting (into

the future) for millions of years (the upper limit then may relate either to a

catastrophic impact or the stage in which the Sun burns out and expands to envelop

the inner planets).

Still another factor that

is not stated in the Drake Equation (or commonly discussed online) is the nature

and strength of the communication signal. Present-day radio waves are probably

too weak to have much effect in all but the nearest part of our galaxy. Higher

energy waves (such as gamma radiation) would be more powerful but we on Earth

have not yet devised suitable transmitters of these rays. And any signal sent

must move away in many directions from it planetary (spherical) source; if only

directional beams are emitted, the number of planetary receivers (made by other

intelligent recipients) in the right position to pick the signals will be greatly

reduced. But, directional beams (those using laser light are especially promising)

have one advantage - they remain concentrated over a small angular volume. As

we on Earth continue to find many more planets (most would be in our Galaxy at

this stage of our detection capabilities), we can systematically send signals

to these with a good chance to intercept them in the narrow field of view encompassing

our signals. Likewise, any intelligent and technically capable life on any one(s)

of these may have by now spotted our solar system and have, or will, send signals

to us. What the "message" should be, owing to uncertainties of language recognition

and translation, is probably dictated by the need to transmit something of a universal

nature: sending intermittent signals (sound or light) that consist of a series

of prime numbers is a favorite suggestion. Since mathematics has a unifying generality

to it - all intelligent beings should find some of the same fundamental theorems

and expressions - the message we receive (or send) is most likely to be in that

format (spoken/written

Start with hypothetical observers

at two points A and B not then in contact in early spacetime. Over expansion time,

their light cones would eventually intersect, allowing each to see (at time t1)

other parts of the Universe in common but not yet one another. At a later time,

beyond t2 ("now") in the future, the horizons of A and B (boundaries

of the two light cones) will finally intersect, allowing each to peer back into

the past history of the other.

language is ruled out because

each one on Earth has a unique set of meanings attached to words that therefore

precludes universality).

All in all, we are still a

"far cry" removed from having any reasonable estimate of probabilities of other

civilizations actually extant. Shermer develops arguments that produce numbers

as low as 2 to 3 for our galaxy (if really strong signals can reach other from

other galaxies, this number would then greatly rise). T.R. McDonough of the Planetary

Society arrives at 4000; Carl Sagan during an optimistic moment, came up with

1,000,000. Today, no one is arriving at zero, so those seeking ET can remain hopeful,

even optimistic.

In October 2001, the Scientific

American magazine carried a review article (pages 61-67) by G. Gonzalez, D. Brownlee,

and P. D. Ward bearing the provocative title of "Refuges for Life in a Hostile

Universe". We will not paraphrase its many intriguing statements and conclusions

but urge you to track the article down and read through it. Its bottom line is

that there appears to be only a narrow range of conditions around stars and within

galaxies that would likely harbor life (organic matter; not necessarily intelligent).

They define CHZ and GHZ as Circumstellar and Glalactic Habitable Zones respectively.

In systems like our Sun's this is confined to a narrow inner zone. In spiral galaxies

the GHZ is beyond the inner bulge, halo, and thick disk that consist mostly of

old stars; the more favorable region is an annulus about midway from the center

to the edge defined by the spiral arms, in that part known as the thin disk.

The condition most pertinent

to possibilities for life is the metallicity of the star groups. Metallicity

defines the proportion or percentage of chemical elements with atomic numbers

above 2 in the total mix of elemental and molecular gases and dust available

for star formation. Smaller stars with metallicities between 60 and 200% of

the Sun's value are favored. These stars comprise about 20% of the total in

a galaxy. Other factors include the frequency of supernovae (which over time

build up the supply of the "metal" atoms), excessive radiation (continuous or

in bursts), and the distribution and numbers of objects capable of destroying

protoplanets by impact. Giant planets seem less likely to foster conditions

that would aid life's establishment. They conclude that 1) most stars don't

have planets and 2) complex life is rare even on those stars with planets. While

they don't propose that Earth is unique, they do caution that the statistical

distribution from their GHZ and CHZ models support the notion that it may prove

very hard to find evidence of life of any kind either in the Milky Way or (even

more so) in more distant galaxies.

The expectation that some

life exists elsewhere in the Universe will depend on the nature of life itself.

Life can be defined by properties that are both chemical and functional. Judging

on what we know conclusively from the one sample available to earthlings - namely,

life on Earth itself as the only confirmed example in the Solar System - the

essential chemical incredients are carbon, the crucial element in organic

molecules (of which proteins are the fundamental component) of great complexity

and variety that are the basis of life, together with hydrogen, oxygen (and

water), nitrogen, and to a lesser degree phosphorus and sulphur and other elements

as important traces. The amazing thing about this assemblage of critical elements

is that they all at times in the past resided in stars and much of the

hydrogen itself can be traced back to the first minute of the Big Bang. You

and I, as humans, are truly star people - our heritage is cosmic in that our

ingredients are either primordial- or stellar-derived.

The principal functional

manifestations of life are: metabolism; reproducibility; cellular-organization;

growth cycle and dependence on nutrition; respiration (in some types); (usually)

movement of some kind; propensity to evolutionary modification, and, for some

types, utilization of photosynthesis. Intelligent life, furthermore, is marked

by consciousness, reasoning, abstraction, reliance on memory, communication,

and awareness of time and other essentials of existence; free will and "soul"

are properties of a more metaphysical nature and harder to prove as realities.

If Earth defines the standard

state, from which there can be no major deviations if life is to form and survive,

then life-supporting planets are constrained to vary in their physical and chemical

properties only within a narrow range. A planet must have accessible and reactive

carbon capable of polymerizing (some have postulated an alternative element, silicon,

as the keystone in complex life-sustaining molecules but no such compounds have

been successfully synthesized and made to function like carbon life). It appears

(but is not totally certain) that water is also essential. If so, in an environ

like Earth, this limits the range of temperatures at which life originates

to the freezing and vaporization (boiling) point values of 0 to 100 °C (however,

life, once formed, has been found to exist at temperatures that are higher and

lower, but generally in the presence of liquid water; witness, the "smokers",

which host symbiotically specialized life, that eject superheated water and steam

on active divergent ridges on the ocean floor). Atmospheres of oxygen and nitrogen

favor many forms of life; planets that are either airless or contain hostile chemicals

such as methane and sulphur compounds tend to suppress life.

If such conditions, and their

ranges, are indeed limiting factors, then only a few, if any, planets in a given

planetary system are properly suited to the origin, development, and persistence

of living creatures. Thus, while billions of planets are probably existent universally

today, only a small fraction are suited to supporting life. These will be confined

to those at a distance from their star where temperatures are in appropriate ranges

to allow water in a suitable state (not chemically bound or heated so that

all has evaporated and escaped to space). They will have proper sizes to maintain

fostering atmospheres. Their chemistry will allow production of molecules (most

likely carbon-based) that can, over time, evolve into organic ones of sufficient

complexity to merit the status of "living".

Water has been detected

in the Solar System, mainly on icy satellites, on Mars, and in comets. A search

for this compound beyond the Solar System has finally met with success. Astronomers

have now detected water around CW Leonus, a carbon-rich star in its waning life,

some 500 l.y. from Earth. This water is believed to now be vapor derived from

billions of comets about the star, as it rapidly releases its heat during an

explosive phase.

The best review of the

Origin of Life found so far by the writer is the 1999 book by Paul Davies, The

Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin and Meaning of Life, Simon &

Schuster.

Whether the evolutionary mechanisms

we have found to operate on Earth - change into diverse and usually more complex

forms in response to changing conditions, aided by genetic processes and natural

selection - lead to intelligent life elsewhere can only so far be the subject

of speculation (devoid of any direct evidence). But, again, considering the large

number of favorable planets - almost certainly in the millions - spread throughout

the billions of galaxies, it would not be surprising, and is to be expected, that

organisms with consciousness and other aspects of intelligence will someday be

communicated with, thus supporting the thesis of Universal life. It is provocative

to conjecture whether these "alien" thinkers have some insight into the concept

of an Intelligent Designer (Creator or God) and whether they believe, as most

here still do, in the special gift of that God of the "soul" destined to persist

in some form of immortality.

Notice that we have progressed

well down this page without mentioning the favorite topic among those - scientists

and laypersons - who speculate on the possibilities and ramifications of intelligent

"alien" life in our galaxy, and by reasonable inference, in most other galaxies:

the reality of whether we have been visited by these creatures in their spaceships

(UFO's) at times in the past, and a corollary, whether we on Earth will ever have

the means to visit other planets by some means of space travel. In light of present

knowledge, any extraterrestrials will almost certainly not originate in any other

solar sytem planet but would reach us from beyond - well into outer space. We,

in turn, must gain experience in space travel by first journeying to one or more

of our neighboring planets. Probably in the lifetime of some who read these words

this will happen. But extending this travel to other stars - interstellar travel

within the Milky Way - may not happen in this timeframe, although 100, 500, 1000,

a million years hence, the advances in science and technology should bring this

about. But, complications and limitations must be overcome.

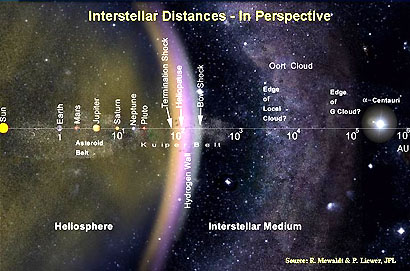

By far the biggest problem

in interstellar travel is distance. A simple example illustrates the difficulty.

The nearest star is Proxima Centauri, 4.2 light years away (actually, Alpha Centauri,

0.1 l.y. farther away, is a better choice owing to its size), or about 42 trillion

kilometers (26 billion miles) from Earth, would be a reasonable first target.

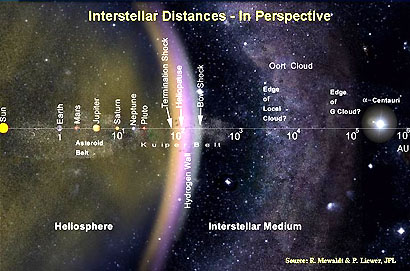

To help you visualize these distances, look at this diagram (the distances are

in Astronomical Units [1 A.U. is the distance between Earth and Sun, or 149 million

kilometers {~93 million miles}]).

If a manned spacecraft were

to leave the solar system at the same velocity that Pioneer 10 had when it actually

did escape the system, namely, 60000 km/hr (37000 mph), it would take approximately

80000 years to reach one of these two stars. (And, the same time to return to

Earth, unless a one-way trip is the choice, then at least double that total.)

This obviously would be impractical under the psychology of today's thinking.

The solution should be obvious: Earthlings must build a spacecraft that contains

all those materials and provisions needed to sustain life for eons. Chief among

these would be foodstuffs, water, oxygen and other essentials. Then, even if human

life spans can be extended, the strategy would still have to be: to continually

recreate people on board through breeding, so that those who arrive at Alpha Centauri

(hopefully, we will discover planets there; none have been detected as yet) will

be many generations down the time path of continuing life of the future. Trips

to other more distant stars may be more enticing if these show evidence of planets

that can sustain life. Surely, from the billions of humans on Earth when this

time of launch comes there may be volunteers who are agreeable to setting forth

on this voyage; if and when we develop the appropriate technology, the travelers

may need to consent to being placed in some kind of suspended animation (a body

freeze technique is commonly proposed to put living creatures into hibernation).

Such a trip is likely to fulfill at least one of four motivations: 1) either the

innate need for man to explore; (2) and/or a desire to establish contact

and exchange knowledge with other civilizations; (3) and/or a compelling

need to survive if Earth should threatened to become uninhabitable); (4)

and/or a decision to colonize another (uninhabited) planet with suitable

living conditions for organisms, or if intelligent beings are found to settle

with them.

However, most readers of

this Tutorial would judge the long duration travel scenario (with or without

hibernation) to be rather undesirable even if altruistic. Is there any alternative.

Yes, if we can find new means of propulsion through space at much greater speeds

than presently achieved. For instance, let the inertial velocity reach 0.2 the

speed of light 'c'. If that occurs soon after launch, the spacecraft should

reach Alpha Centauri in 5 x 4.3 l.y., or 21 years (earthtime), or 42+ years

roundtrip. Theoretically, this transit time can be greatly shortened if the

spacecraft attains a velocity near light speed. However, relativistic effects

will come into play (see Preface to this Section), including differential aging

between space travelers and those remaining on Earth. Thus, time dilation would

make the high speed trip appear to those on Earth to have taken longer than

the 4.2 years plus adjustments for being somewhat under light speed.

There are many other factors

required for success and safety to take into consideration. Perhaps at the top

of the list is to find propulsion systems that can reach these high speeds (significant

fractions of the speed of light); to get to such speeds requires huge expenditures

of energy. Presently, none is known, but some sound proposals for possibilities

already have surfaced: ion engines, anti-matter engines, controlled nuclear

processes, gravitational "slings", laser beams pushing on light sails, and various

other innovative but speculative mechanisms for powerful propulsion systems.

Quantum-minded thinkers can conjure up schemes that depend on "wormholes" and

"quantum tunneling", "timewarps", and the like. A long shot depends on the proof

of existence of the hypothesized "tachyons", particles that travel at faster

than the speed of light; if real and accessible, some technique would be needed

to harness them as aids to propulsion. Whatever propulsion systems is eventually

proven feasible, one requisite is that it be one that travels with the spacecraft

(instead of a "one-shot" push at the outset) so that there would always be a

means for course corrections, maneuvering, handling the unforseen, possible

landing, and eventual return to Earth if that is a mission requirement. If we

base our predictions for space travel eventuality on the huge advances in science

and technology over the last two centuries - now seeming to occur as though

growing exponentially - it is reasonable to expect that the possibility of interstellar

travel will turn into reality in the not too distant future (say, in this millenium).

If that indeed happens, then the counterpoint argument is that aliens "out there"

may be ahead of us and have in fact visited Earth - if we are judged to be interesting

enough.

These last paragraphs have

no doubt been fascinating for some. There are a large number of books devoted

to this mind-boggling subject. These are referenced on the Internet; just use

your Search Engine to look for topics such as "Space travel", "Interstellar travel",

or similar keywords. The writer found many that discuss the potentialities and

the difficulties underlying outer space exploration; here are two of these URLs:

(1); (3)

To sum up the hard realities

of space travel: 1) present and foreseeable technologies still far short of

making such trips plausible, safe and worthwhile 2) in time (probably many centuries),

humans may learn enough to engage in such endeavors; 3) almost certainly, a

manned trip will be preceded by unmanned spacecraft to prove the workability

of the technology; 4) if mankind survives itself (or evolves into some form

of superintelligence that can control the various threats to self-destruction

(wars; environmental nihilism), trips to other stars will someday be inevitable;

and 5) in the meantime, we should continue to inventory suitable planets and

search for intelligent life elsewhere (SETI), so as to develop the incentive

for undertaking travel to candidate planets; we should also hunt for any evidence

that Earth has previously been visited (the Fermi Paradox: If aliens have already

come to Earth, as might be expected since statistically there could well be

many more advanced civilizations than those on Earth today if intelligent life

is widespread in the Universe, then why haven't we found any valid signs of

their visit?)

In closing Section 20,

contemplation of Cosmology, and its astronomical substructure, is a truly humbling

experience for one's brain. The wonder is: that there exists on one tiny point

in a humongous Universe something called the "conscious" and that the human

mind (yours, for instance) can conceive of, and begin to understand, the truths

of this Universe's attributes and history that are continually being discovered

and refined. Finally, it is both astonishing and reassuring to realize that

all beings - be they people or animals/plants or inanimate matter - are remarkably

cosmological in nature: All the atoms in our bodies were once contained in stars

or interstellar space; our parts in a sense are variously billions of years

old and their atomic constituents, even after multiple dispersions and reassemblies,

will last at least as long as the present Universe - estimated to continue for

perhaps 50 b.y or more. In one way, then, our essences will have achieved some

kind of plausible Immortality in view of the many incarnations that preceded

our current atomic arrangement and are yet to happen. But, from the humble side,

perhaps "We are not alone" and certainly we are not at the center of the known

Universe; our importance is sui generis and our rank among the Universe's

populations is probably just average.

This Section on Cosmology

has doubtless been heavy going for most readers. Some may be inspired to wish

to learn more. Refer to the Preface link accessed from page 20-1 for the references

to books consulted by the writer in preparing this overview:

For those who would like to

learn much more about astronomy through illustrations, we want to steer you to

a Web site that allows you to seek more pictures and textual information about

most of the topics that have been covered or touched upon so far in this Appendix.

NASA Goddard astronomers have put together a Web site that features many previous

Astronomy Picture

of the Day (APOD). In the Search box, you simply type in a topic, e.g., young

stars; supernova; black holes; spiral galaxies, planet, etc. and if the category

is there a running text with links to subtopics and pictures will be delivered.

This can be an adventure.

And, finally, here is a

quiz of sorts - actually a Web Page that poses many questions (FACs) coming

from those who have accessed the site. Many of these you should be able to answer

now that you have gone through this Section. Others touch upon topics that may

not have been considered before. Still others provide concise reviews of ideas

we've presented but perhaps will give you a different slant or will offer supplemental

information. Anyway, log on to "Ask the Space Scientist"

and choose the group of topics that obviously fall within The Cosmos pervue.

But, you may also want to check out the Planetology group or even some of the

other subjects.

Some Additional

Comments

For the curious, these paperback

books by Paul Davies offer valuable insights into both scientific and metaphysical

aspects of Cosmology: God and the New Physics and The Mind of God

[especially Ch. 2]., Touchstone Books, Simon & Schuster, Inc.; this author

considers the question of life elsewhere in the Universe in Are We Alone: Philosophical

Implications of the Discovery of Extraterrestrial Life, Basic Books, 1995.

A book that relates cosmological discoveries to teachings associated with the

Christian God is Beyond the Cosmos by Hugh Ross, Oxford Press, 1996. A

balanced review that considers how religious beliefs and observations of the physical

Universe are not necessarily incompatible is When Science meets Religion

by Ian Barbour, Harper, 1999. A general overview of arguments contrary to the

exclusively natural and spontaneous Universe such as described in this Section

is A Case against Accident and Self-Organization, Rowman & Littlefield.

In the March, 2002 issue of

the magazine First Things, which deals with topics in philosophy, theology,

and the social order, an outstanding review of the possibilities of life elsewhere

in the Universe and its implications for humankind, written by Fred Heeren, and

entitled Home Alone in the Universe?, provides comprehensive and provocative

insights into the question of how discovery of intelligent life beyond the Solar

System would affect and change the outlook of Earth's inhabitants towards their

place and role in the Universe. Highly recommended! And, as of August, 2002, the

full text remains online at this URL.

Two Internet Sites that

address the possibilities of other worlds, extraterrestrial life, and the implications

that such life, and cosmology in general, would have on the religions of our

world has been prepared by Florida

Today and Stanford Encyclopedia

(the latter rather heavy-going).

And last (but hopefully

not least) you have the option of clicking here to read two letters

written by the writer (NMS) to his local newspaper (The Press-Enterprise) as

he joined a running debate on the editorial pages between one faction - the

conservative Creationists - and another - the progressive Scientists - concerning

the role that a God-Creator may have had in producing the Universe we have just

been studying. The ideas in these two letters summarize my still developing

viewpoint on the philosophical/scientific interweavings of the notions that

God does/does not (+/-) exist. Read these letters if you are curious.