Evidence

for the Big Bang:

The Redshift; Stellar/Galactic Distances; Age of the Universe;

Cosmic Background Radiation; Expansion Models; Dark Matter/Energy

What evidence leads to

and supports the Big Bang model? A good review of the resulting expansion (and

calculated rates) and ages derived from these observations can be found in a

Scientific American article (October, 1998; pp. 92-96) prepared by Dr. Wendy

L. Freedman.

Two

accepted lines of proof for the Big Bang have already been described: 1) the

details of the creation physics and progressive emergence of various elementary

particles during the first minute of the Big Bang (the Standard Model and its

variants; review page page 20-1) are consistent with

a model based on Big Bang precepts; these particles are the outcome of a history

that can be predicted and explained by Quantum and High Energy Physics, that

is, the theoretical production and sequence of particles seems verified by the

observed amounts of H, He, and Li atoms in the Universe; and 2) the observations,

particularly from HST, of the farthest galaxies as being more primitive in appearance

and development, are precisely what is expected from the expansion model in

which those parts of space (in which the galaxies are embedded) that have moved

the fastest are now the most distant; thus, we see them in earlier stages of

evolution when they were younger as we look back in time outwards from our frame

of reference,.

But, even more convincing

are two other physical observations that are best explained by a Big Bang origin

for the Universe, especially in terms of its expansion behavior: redshifts

of light (towards longer wavelengths) from the stars as a composite source in

galaxies and cosmic background radiation.

Redshift

and the Hubble Law

The first derives from relative

velocities as divulged by the measured redshift of radiation wavelengths

(see below for details). This was formalized by V.M. Slipher in 1912 but, in fact,

H. Robertson noticed a bit earlier that the farther nearby galaxies were from

our telescopes, the greater was the redshift. However, Edwin Hubble in 1924 has

received credit for promulgating this redshift-velocity-distance relationship

because he included many more galaxies as data points. He thus is recognized as

the key individual behind the Expanding Universe model, from whence later came

the Big Bang conception of its origin. (Note: Hubble himself never completely

accepted the implications of his observations and had doubts about the Big Bang

and most of the Universe models described below; for many years after drawing

attention to this phenomenon he continued to prefer a Steady State rather than

an Expanding Universe, although his position on the latter "mellowed" near the

end of his life.)

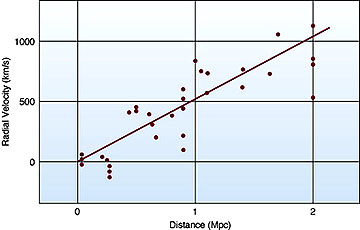

Some of Hubble's observed

redshifts led to estimates of galaxy velocities of 100 million kph, about 0.1

the speed of light. Here is a plot of his original data, from which he deduced

the expansion concept that later led to the Big Bang model

Hubble noted that, as recessional

velocities Vr were measured for stellar sources over a wide range of

astronomical distances D, the plot of Vr/D disclosed a straight line

relation whose slope has a value H, known as the Hubble Constant, named

after him. This, the Hubble Law, is the fundamental statement of the Big

Bang model. Here is one of his published plots of velocity versus distance.

From Astronomica.org

The resulting straight

line plot is easily described mathematically, in the basic equation:

Vr

(velocity of recession) = H (the constant determining slope) x D (distance [from

observer])

The constant has been designated

by the letter H, and is called the Hubble Constant. It is normally given the units

of Km/sec/Megaparsec (an alternate form is km/sec/million light years). The prime

information derived from this equation is that objects (such as galaxies) appear

to travel at ever increasing velocities as their distance from the observer (Earth)

becomes ever greater. The upper limit to expansion rate is the speed of light

(although some interpretations of inflation suggest that this huge leap in dimensional

enlargement occurred at greater than light speed). The current rate of expansion

is specified as one light year per Earth year (think about this and its logic

should be revealed).

One problem troubling Hubble

in the early years after his discovery is that when he used the first value for

H he derived to calculate the age of the Universe, it came out around 2+ billion

years, a number in stark conflict with the then accepted age of the Earth at about

4 billion years. The contradiction resulted from very imperfect - and too small

- estimates of distance to the nearby galaxies he used. As more trustworthy values

were obtained, and elliptical galaxies further out were better fixed as to distance,

an improved curve resulted (but still applicable to redshift z values [see below]

of less than 1):

From Astronomica.org

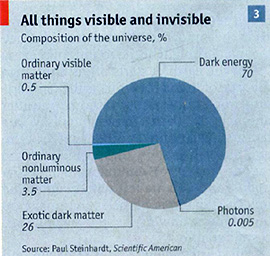

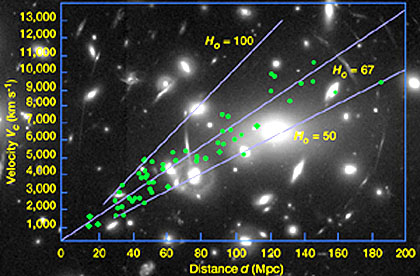

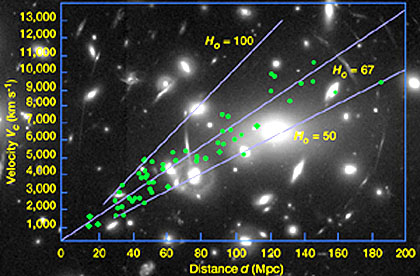

The diagram below is a recent

plot of galaxy velocity (in km/sec; converted to kph by multiplying by 3600) versus

distance (in megaparsecs) of each galaxy from Earth; the green dots denote specific

galaxies for which "reasonably good" measurements have been made (other galaxies

have also been so measured but their values are not on this diagram). Most of

these values come from galaxies 5 billion or less light years away. H0

is the present-day Hubble Constant whose precise value is still a major goal in

cosmological research; its spread of estimates is related to the uncertainties

both in determining the redshift and in fixing the distance of a galaxy at the

time light now received left it.

The Hubble Law works best

(gives a straight line) from plots of V versus D involving galaxies a few billion

or less light years away; uncertainties as to the correctness of distances further

out cause an increasing scatter of points in the plot that suggest (or mask) some

degree of non-linearity related to the cumulative effects of the curvature of

space.

Although called a "constant",

H has in fact varied in value over time. In this, it behaves much like the three

non-linear plots of R (Scale Factor) versus time shown on the previous page. R

describes how distances (as a measured parameter) change over time; H relates

distance traveled in a unit time span at each distance moving outward from the

point of observation. The two are related. H refers to the relative rate of change

of R. The reason that H has different values going back through the past is that

it is unlikely that the expansion rate of the Universe has itself been constant

since the Big Bang. Until recently, one model of expansion is strongly influenced

by deceleration due to gravitational forces pulling back on the enlarging universe,

which means the rate of expansion has been continually decreasing, giving rise

to a systematically changing H over the past (its value would increase as we move

back in time towards the outer Universe). But now, new evidence for a gradual

acceleration about midtime in the Universe's history (see next page) would also

affect the variability of H. At best, we can now only determine with reasonable

accuracy the value of H0, which proxies for the current value that

takes into account the variations in earlier eons of the Universe. We can also

say that H was at its maximum value relative to the present right after the extremely

large (anomalous) expansion rate of Inflation; we cannot measure this value since

we are unable to determine any redshifts until the Universe became transparent.

Let us now look into the details

of the concept of "redshift". Increases in recessional velocities are associated

with changes in the wavelength of light being received, such that as the velocity

becomes greater the wavelength becomes longer, i.e, moves to higher values (say,

from 0.4 to 0.6 µm in the visible; wavelengths in other regions of the EM spectrum

also are shifted towards greater values). This change is very much like the Doppler

effect studied in Introductory Physics: this shows the influence of motion towards

or away from the observer of a signal of some given wavelength, resulting in a

systematic wavelength shift. One manifestation of a wavelength shift's effect,

which can be experienced in everyday life on Earth, is exemplified by an audible

phenomenon - recall the sound of a whistle or horn on a fast-moving train as it

approaches and then moves past where you are stopped at a crossing. The pitch

of the sound varies systematically, rising on approach (higher frequencies) and

then falling as the train recedes after passing (lower frequencies). This wavelength

shortening (higher pitch) on approach and lengthening (lower pitch) with recession

is called the Doppler effect, which results from velocity and/or position

changes (relative motions) between moving source and stationary receiver.

In a sense, the lengthening

of wavelength as light sources (mostly galaxies) recede from Earth at progressively

increasing velocities and distances is analogous to the above Doppler effect.

Strictly speaking, this familiar effect as observed by us on Earth is not the

same as applies to cosmic distances (although it is a good approximation for nearby

galaxies in relative motion away from our observing location). As applied to more

distant objects seemingly moving away from us during Universe expansion, the wavelength

shift actually results from a different mechanism known as the Cosmological

Redshift. From a relativistic standpoint, while Dopplerlike in its consequences,

the cosmological redshift is analogous to the "stretching" of light caused by

the progressive increases in distance resulting from the continuous expansion

of (curving) space. This in turn results in proportional increases in recessional

velocities (thus in the formula for velocity v = d/t, it is the d that changes

with respect to steady time progression) with increasing distance from Earth (recall

the rubber band analogy on page

20-8).

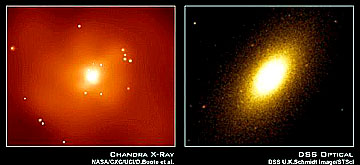

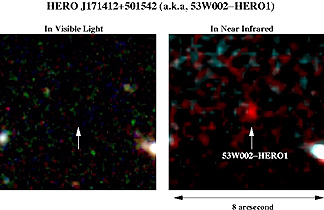

A recently reported observation

of a type of galactic body called a HERO (Hyper Extremely Red Object) may be

the result of this cosmological redshift. Check these two images:

On the left, the object

is not detected in visible light; but it appears as a red blotch in the near

infrared. The object, at least 10 billion light years from Earth, has been found

to be speeding away from us at nearly the speed of light. One interpretation

considers this object to be red (from a large propoortion of older stars) at

the time its light left the source 10 b.y. ago . But another considers this

this object to be composed in large part of bright, bluish stars, perhaps even

farther away (13 billion l.y.) but owing to the cosmological redshift the light

as received has been stretched to near infrared wavelengths (but assigned red

in this false color rendition).

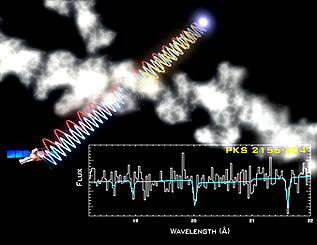

Redshift phenomena are effectively

studied from their spectral states. As a star or galaxy emitting radiation recedes

from an observing (measuring) spectrometer (somewhere on or near the Earth), the

wavelength associated with a particular line will be shifted towards the red (longer

wavelength-lower energy end of the visible spectrum) and even into the near infrared.

What is measured is the displacement (δλ/λ = the incremental wavelength

shift ratioed to its initial wavelength λ) of this line to a new apparent

wavelength relative to its [rest state] wavelength in a spectrum obtained by exciting

the element on Earth in an emission or absorption spectrometer. The spectra are

commonly recorded on a photographic plate showing multiple lines that result from

the spectral spread of wavelengths characteristic of all detected elements) representing

an element in its ground or some excited state in the visible.

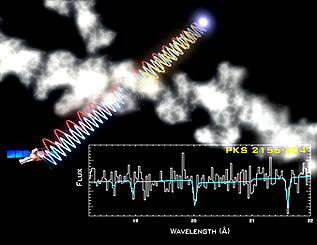

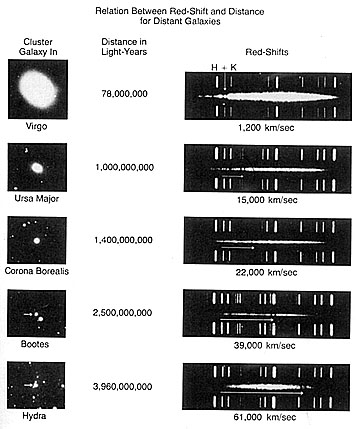

This next illustration shows

telescope images and spectra from five galaxies at increasing distances from Earth.

From J.

Silk, The Big Bang, 2nd Ed.

To pick out and thus intrepret

these spectra, start with the Virgo galaxy example (top right). The top and

bottom lines are the same emission spectra for this spectral interval (unspecified;

they are white instead of black because the photographic plate is printed as

a negative) obtained by spectroscopic analysis of a sample on Earth. The two

leftmost lines are the H and K spectra for the excited Ca++ state.

The spectrum from the galaxy appears as a long lenticular white smear in between

the two reference spectra. The vertical arrow points to the now shifted H and

K line pair, which here appear black because they are absorption rather than

emission lines. In the second spectral image, the horizontal arrow leads to

the position of the line pair for a galaxy in Ursa Major, now shifted notably

to the right. In the three succeeding spectal images, the horizontal arrow carries

to the position of the two dark H and K lines after each greater redshift. From

these observed shifts, the recessional velocities listed under each spectral

image have been calculated. These could be plotted on the distance-recessional

velocity diagram above, and would fall within the general distribution shown

thereon.

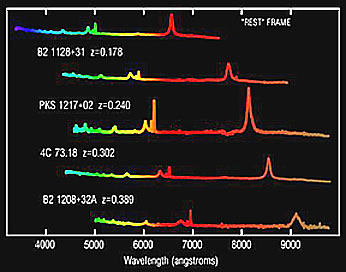

Today, the spectra are

more commonly recorded as continuous tracings on a strip chart. The next figure

shows a spectrogram recorded by a Kitt Peak National Observatory telescope in

which the top spectrum (obtained at rest in the laboratory) has peaks for three

hydrogen lines at 4340 A (in the blue); 4860 A (green) and 6552 A (red). The

next four are spectra from distant quasars at progressively greater distances.

Source:

M. Corbin

The displacement of a spectral

line owing to redshift can be used to calculate the redshift value z associated

with a source simply from the rest wavelength of a given line and the observed

wavelength of the same line displaced by the source's motion: The formula:

z = (λobs/λrest)

- 1

Using the z value,

the velocity v of receding motion of the source is given by:

v = cz

(1 + 0.5z)/(1 + z)

Since the redshift is velocity

dependent, its magnitude is a direct indication of the rate of recession, i.e.,

the larger the shift, the greater the velocity. The redshift z is a number that

represents the fraction by which spectral lines from a luminous source shift

towards longer wavelengths. Values of z range from less than one for closer

sources and have risen for the most distant sources (early time galaxies) to

numbers around 6.

If instead the source advances

towards the observer, the shift will be towards the blue (shorter wavelengths).

Since it is postulated in the Big Bang model that all sources are apparently moving

away from one another, a blueshift would seem anomalous. However, this

occurs, for example, when spectra are acquired from a rotating spiral galaxy in

which arms on one side (from the center) may indeed be moving away but the other

side must be approaching from opposite directions. Likewise, some galaxies in

a local group may appear to be moving towards Earth towards Earth, but the entire

group is still receding relative to our galaxy.

Another mechanism can cause

redshifts, namely, the effects of gravity on radiation. This gravitational

redshift is a consequence of General Relativity. When light leaves a massive

gravitational source, such as a White Dwarf, gravity causes a shift towards a

longer wavelength (conversely, light passing into a huge gravitational field will

undergo a blueshift). The massive body thus slows down photons representing a

range of energies as these escape from it, causing a loss in their energies that

results in reducing their frequencies and increasing their wavelengths This effect

has been observed for light grazing supermassive bodies, including Black Holes.

Overall, the effect is localized or confined to individual bodies, and

normally the shift is very small, so that even the cumulative effects of light

reach Earth from the outermost reaches of Space are quite small compared with

the motion-induced Cosmological Redshifts related to expansion. Nevertheless this

local redshift must be accounted for when individual receding galaxies are used

in determining the cosmological-scale redshifts.

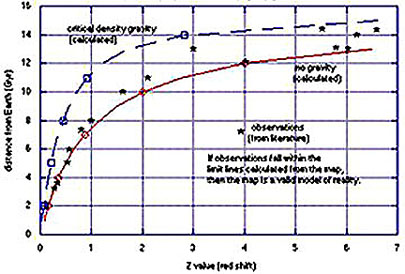

There is another, more

general effect of gravity, shown in the plot below, which shows the redshift

curve for a Universe with maximum gravity influence versus no gravity at all.

This range of possibilities is pertinent to the accelerating Universe model

discussed on the next page.

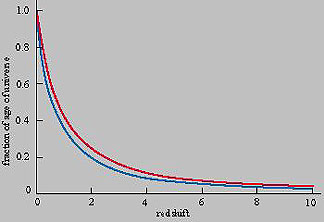

A variant of this is shown

in this figure:

The ordinate denotes relative

age: At this time, that can be given by "1", with those nearby galaxies that

appear most fully evolved (to the present time) having very low redshifts. The

exponental drop in the curves (the red curve applies to a Universe with 70%

Dark Matter; the blue curve described a Universe without Dark Energy [Cosmological

Constant = 0) shows that the maximum rate of increase in the value of 'z' occurred

when the Universe was less than a relative 0.2.

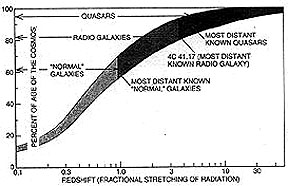

Most redshifts measured

so far include the lower values of z obtained by examining a range of "normal"

galaxies at distances from Earth under about 7 billion light years. Higher redshifts

have been found for galaxies that are strong radio sources and even larger values

(around z = 5 to 6.5) from very distant quasars (mainly those which display

their effects in the first two billion years of Universe history). Values of

'z' increase rapidly towards infinity for Universe events older than the first

stars. For instance, at the time of Recombination (page 20-1) z = 1000. This

is the general relationship as tied to major cosmological entities:

Stellar

and Galactic Distances (from Earth)

To apply the redshift to estimate

R (Scale Factor), and to determine the Hubble contant H, the distances to the

shifting bodies must be specified. Distance measurements obtained for nearby bodies,

e.g., in our own Milky Way galaxy, can be made on visible stars whose magnitudes

can be directly ascertained. One technique is that of parallax observations. While

not fully explained here, the gist of this technique can be sensed by this simple

experiment: Hold your index finger first about 6 inches in front of your nose

and rapidly alternately close your left eye and then right one repeatedly. Your

finger will appear to shift back and forth relative to a fixed background, perhaps

seeming to displace several inches. Now, put your finger full out (about 24 inches)

and do the same thing. Note that the displacement is now less. This is the parallax

effect. The amount of shift decreases with increasing distance and that distance

can be determined by simple trigonometry. As used to measure stars within about

100 parsecs (326 light years), the left and right eye positions are proxied by

the positions at opposite points in the Earth's elliptical orbit six months apart.

A star's apparent shift relative to distant background stars, even though proportionately

much smaller than that of the finger experiment, is sufficient to provide an accurate

distance measure for stellar bodies close to Earth.

Redshift measurements for

more distant starlike bodies are actually made on galaxies (their individual stars

may not be resolvable) whose luminosities are the average of all component stars.

Approximate distances to much closer host galaxies containing separable stars

rely on determining the intrinsic luminosity of certain types of individual stars.

One class is the so-called pulsating stars, i.e., those whose luminosities vary

systematically over periods of days to several months. These include stars that

have used up nearly all of their hydrogen fuel and are enroute off the Main Sequence

towards then becoming Red supergiants. During this phase of their history, their

atmospheres expand rapidly with a rise in luminosity, only to revert back to their

previous state during a cycle whose time is that of a regular period. What happens

is this: the star in its more compact state has a specific internal pressure;

at some point the nuclear processes cause the star to expand, increasing its diameter

by a factor around 2. The pressure gradient decreases until a condition is reached

in which gravity now reverses the process causing contraction. The expansion-contraction

repeats at its characterist nearly constant time period (in Earth days) for a

long time before a particular pulsating star evolves into a more stable Red (Super)Giant.

Most stars showing this phenomenon have initial masses from 5 to 20 times that

of the Sun. More massive stars have longer periods of expansion-contraction and

are also more luminous to start with.

One class of periodically

pulsing star group are the RR-Lyrae stars whose periods are in hours to a single

day. More important are the Cepheid supergiant stars. Cepheids were first

discovered by astronomer Henrietta Leavitt in 1912 in the nearby Magellanic Clouds;

she then showed them to have regular, pulsating variations in luminosity proportional

to their pulse periods (in so doing, determined that the brighter the star, the

longer its period P). Cepheids flare up to peak brightnesses, then dim

down, over periods of days to weeks. Using the parallax method, the distances

to some of these were independently fixed and their absolute magnitudes M

were calculated. Since these distances varied (within the Milky Way and in the

Magellanic Clouds), the various M values could be associated with their corresponding

periods in the cycle, thus establishing the M-P relationship. Of course, Cepheids

having the same values of M but located at widely varying distances from Earth

will experience an apparent decrease in brightness m depending on distance

(and subject to the 1/d2 relation that defines the falloff in brightness

with distance). These ideas are illustrated for one of the type Cepheids (δ-Cephei).

Once absolute luminosity for

a given Cepheid is calibrated from this relation, the drop in apparent (observed)

brightness m from that value owing to its specific distance d can

then be included in the following equation to determine that distance to this

star:

m - M

= 5(log d/10)

In the 1920s, Edwin Hubble

more firmly established the relation that the longer the period, the greater

is the increase in the intrinsic (absolute) brightness in a Cepheid. He applied

this pulse cycle approach to these stars in different galaxies and over a range

of distances. It was Hubble's use of primarily Cepheid-derived distances that

led to his first major hypothesis of an expanding Universe, after also introducing

the redshift relation. Some of the values he used were not highly accurate (but

were later corrected) so that his initial postulated rates of expansion were

considerably off-the-mark.

The Cepheid variable star

method works well out to a distance of 50 million light years (roughly, out to

Virgo). For galaxies farther away, other methods of measuring distances to them

(such as the rich cluster- brightest galaxy indicator which gives usable approximations

out to 10 billion l.y.) have been worked out and applied (they have varying degrees

of accuracy. Use of multiple methods applicable at different distances is called

the Cosmic Distance Ladder. To sum up: Among these methods are (in order

of usefulness at increasing distances: 1) Parallax; 2) Moving Cluster; 3) Color-Magnitude;

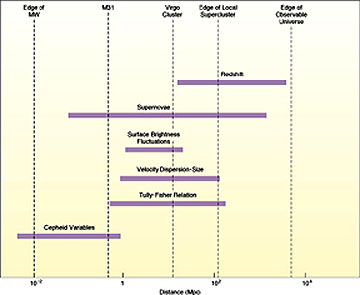

4) Period-Luminosity (Cepheids); 5) Supernovae. This diagram shows several of

these and some other methods; the abscissa in the chart is in units of Megaparsecs.

A good, in-depth review of the principal methods used in distance determination

is found at Ned Wrights Cosmology site.

From Astronomica.org

The Cosmological Redshift

z is given as: z = ( rec -

rec -  em)/

em)/ em

= Vr/c, where

em

= Vr/c, where  em is the wavelength

given out in the past (then) at the emitting galaxy or star,

em is the wavelength

given out in the past (then) at the emitting galaxy or star,  rec

is the shifted wavelength received today (now) at the detector (on Earth),

Vr is the recessional velocity for the particular redshift, and c is

the speed of light. (The above equation applies to low to moderate z's but for

large z's, which are attained as the velocities near that of light speed (and

are characteristics of the early moments of the Universe) a modified expression

must be used:

rec

is the shifted wavelength received today (now) at the detector (on Earth),

Vr is the recessional velocity for the particular redshift, and c is

the speed of light. (The above equation applies to low to moderate z's but for

large z's, which are attained as the velocities near that of light speed (and

are characteristics of the early moments of the Universe) a modified expression

must be used:

z + 1 =

(1 + v/c)/(1 + v2/c2)1/2

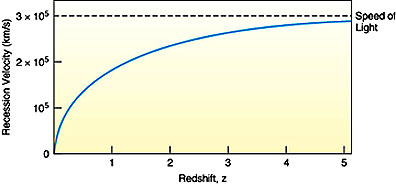

When redshifts begin to

exceed about 1, the speeds of the objects concerned begin to approach relativistic

values, i.e., they are ever larger fractions of the speed of light. Thus, although

the actual speeds continue to increase, the incremental rate of velocity increase

itself decreases (slope asymptote approaches 0). This gives rise to a redshift

vs recessional speed curve that is like this:

From Astronomica.com

Another relationship: z =

1/R(tem) - 1 describes the redshift in terms of the Scale Factor R

pertinent to tem which refers to the particular time when the light

was emitted . This relationship can also be cast in the following way:

Dnow/Dthen

= Rnow/Rthen = z + 1 = λrec/λem,

in which Dnow is

the distance to the emitter when the light is received and Dthen refers

to the distance in the past when light left the emitter.

We see a redshift (towards

longer wavelengths) because the Universe had a different Scale Factor when the

light left the emitter. The redshift is due to the relative expansion of space

(increasing "D's" [for distance]) rather than actual speeding up of more distant

galaxies. Look at the two circle drawing shown earlier on page 20-8. Note the S-like

curl that represents part of a wavelength train. It has a shorter wavelength in

the left circle; as the circle expands with its enlarged coordinates, note that

the wavelength on the right is now longer.

Before new data from the HST

and other observing systems, the present-day value of H (i.e., H0)

had fallen to between 50 to 100 km/sec/Megaparsecs (a parsec is 3.26 l.y). (In

some expressions of H, megaparsecs are replaced by 1 million (106)

light years; thus 75 km/sec/Mpc = 23 km/sec/106 l.y.) One goal of the

Hubble Telescope is to better zero in on the most accurate value of H - essential

to an accurate estimate of the Universe's age. From most recent best estimates,

a range of H0 (value at the present time) between 65 and 79 km/sec/Mpc

is considered the most likely to contain the eventual most accurate value (still

being sought).

Cosmic

Ages

The general relation for the

Universe's age (since the Big Bang) is given by the expression: t0

= 1/H0. In the actual calculations, when H units (in the Mpc mode)

are adjusted to give an answer in billions of years, the formula becomes: Age

= 977.8/H0. For an H0 of 65 km/sec/Mpc, the formula gives

an age of 15.04 billion years (estimated uncertainty is +/- 2 billion years).

Currently,

13.5 billion years (H0

= 72.5 km/sec/Mpc) is the most widely accepted value (ages between 14 and 15 billion

years are also quoted in papers published in the last few years). The lower the

value of H, the larger is t0 and thus the Universe becomes older.

The formula t0

= 1/H0 is deceptively simple. Just putting in a value for H0

yields a number that is not years as such. The proper units must be included.

Here we will run through the calculation that leads to the end-result age for

a value of H0 = 70 km/s/Mpc (s = sec; Mpc must be converted into

mega-light years):

t (109

years) = 1/70 km/s/Mpc x 3.26 Mly/Mpc X 106 ly/Mly

X 9.46 x 1012 km/ly X 1/3.15 x 107

s/year = 14.02 billion years

(Note: / denotes values

to its right are in the denominator of that term; X is the multiplier sign

between terms.)

However, the Hubble Age also

depends on whether the Universe is open, closed, or flat, and may be influenced

by the type of space involved (see below). In the absence of gravity the value

of tH is 1/H0. The Hubble age for a Universe with flat expansion

varies as the relation tH = 0.67/H0 (this applies to the

Einstein-DeSitter Universe [see below]). For an open Universe, tH falls

between 1 and 0.67. For a closed Universe, tH can be less than 0.67.

These several cases for ages that are less than 1/H seemingly point to Universes

that began less than ~14 billion years ago. But, if the ages of the most distant

galaxies, now only estimated from distance-brightness relations, prove to be around

that value, then the resulting paradox - parts are older than the whole - will

need to be explained away. To some extent, resolving this paradox can help to

specify the type of Universe that actually exists, since age-incompatible situations

would seem to argue against the types that don't fit.

Over the past 5 years, observational

data analyzed by HST Teams whose prime task is to try to pin down the Universe's

age using a better determined Hubble constant suggested in May of 1999 a best

estimate for the Hubble constant of 70 km/sec/Mpc. (That number also coincides

with the local expansion rate based on redshift-distance measurements for galaxies

near the Milky Way.) For the H range they arrived at, an age of 12 to 13.5 billion

years would result. The age uncertainty represents an accuracy variation to within

+/- 10% for the value of this constant. Their value depends on analysis of redshifts

in 18 galaxies within 67 million l.y. from Earth; in these they have found up

to 800 Cepheid variable stars which are the most reliable indicators of large

distances. From the combined determinations for the 18 galaxies, this best estimate

of expansion rate gives an increase in velocity of 256,000 km/hr (160,000 mph)

for every 3.3 million l.y. farther out the stellar entity (galaxy or individual

stars) is from Earth.

Most astronomers disputed

the above age conclusion based on the galaxy distance model, citing older ages

according to their calculations and their interpretation of H values using different

inputs. In the last few years most cosmologists (e.g., Alan Sandage and associates)

are advocating a value of H that yields an age closer to 14 Ga; this recent

age is now the preferred "best estimate". However, a vital note of caution: As

more galaxies at great distances from Earth are detected and measured astrometrically,

so that their intrinsic brightnesses, distances, and redshifts are known with

notable accuracy, the value of H could be recalculated to a lower number. This

would mean an older Universe (greater than 14 Ga) and would mean that the oldest

galaxies now known lie well within the limits of the knowable Cosmos. Said another

way: there may be considerably more space beyond our present observable Universe,

that is where our time horizon now extends, and this additional outer volume would

likely contain galaxies. This can be assessed when/if we can see the outermost,

already detected galaxies in such detail that we can specify how primitive or

early they are in their evolution. If they appear to be in the first stages of

formation, if we know enough about their rates of growth, and if galaxies indeed

to form within the first billion years after the Big Bang, then these galaxies

are probably near the edge of the expanding Universe, with little or no space

beyond. This does not rule out an infinite Universe, if it is destined to continue

expanding into an infinite future.

The first reported (before

1995) HST-derived ages fell between 8-12 Ga, anomalously low compared with pre-Hubble

reported ranges of 12 - 18 Ga. This was especially confusing in that separate

evidence and theoretical calculations indicate some distant galaxies might well

be 13 Ga and possibly older. This Age Paradox - stars seemingly older than the

Big Bang's start time - proved particularly troubling to cosmological theorists

for several years. The problem was minimized with further studies of nearby globular

clusters which contain very old stars. These clusters formed along with the organization

of the oldest galaxies around which the clusters are tied by gravity within the

galactic halos. Data from the Hipparcos astronomical satellite led to a redetermination

of globular cluster luminosities, and correlative rates of fuel consumption. From

this new information the average ages of clusters was reduced by 14% so that their

oldest stars (Red Giants) could not be older than the 13 Ga cited above. This,

together with the more refined 13-14 billion year Hubble age (see below), obviates

the discrepancy posed by the Paradox. One consequence of this most recent age

estimate is that the farthest galaxies whose distances from Earth is said to be

13 billion l.y., and possibly a few yet to be detected that are even farther away

(older) (page 20-8), must lie near the

observable edge of the Universe.

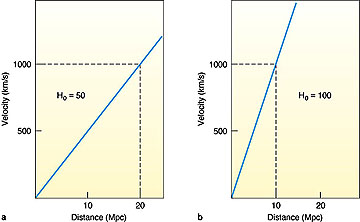

Thus, from the above, variations

in the chosen value for H0 have a major, definitive influence on

two fundamental cosmological parameters that scientists seek to know "exactly"

- the size of the observable Universe and the age of the Universe. This notion

is brought home by considering the consequences of changing the H0

value, as is done in this figure:

The question to ask in

interpreting these H curves is which one leads to a younger Universe; which

Universe is smaller? Check the conclusion by clicking on this *.

The critical factors determining

the Universe's age are its overall density (mass and energy) and the value of

the Deceleration Parameter (related to the Hubble Scale Factor), as discussed

elsewhere on this page. These specify the rate of expansion which in turn reveals

how long it takes for galaxies to get to the farthest reaches of observable

space (i.e., the limits or horizon defined as the farthest bodies that have emitted

radiation which has had time since the beginning of the Universe to travel to

Earth's observing stations; this will be marked by the first vestiges of materials

capable of emitting detectable radiation during the early moments of the Big Bang;

so far, detectors covering optical and other spectral regions have not yet picked

out these oldest sources, so the currently observable Universe presently is smaller

than the total observable Universe).

The Hubble equation specifies

that the fastest receding objects must be farthest away; conversely, those near

the Milky Way are the slowest moving. Thus, in an expanding Universe, with all

galaxies ultimately drawing apart from each other, those progressively farther

away must travel at proportionately greater speeds, but at the same rates in all

directions, to preserve an overall uniformity of spatial relations during these

expansive movements. As a general rule, the greater the lookback time,

the smaller was the size of the Universe at such times, and the hotter and denser

is the early expansion status of matter and energy. (Lookback time connotes the

idea that the farther out in space one looks, the further back in time [earlier]

is the event or stage of development associated with objects [e.g., galaxies]

when light left them; a large Lookback time means a younger age]).

Because most galactic measurements

made on distant galaxies show red rather than blue shifts (the latter are seen

for mostly nearby galaxies moving towards us [Andromeda is approaching Earth at

~360,000 kph] or can be noted in individual spiral galaxies as one arm moves towards

Earth), this evidence for overall (net) recession is the principal proof for the

Big Bang expansion model. The redshift is related to recessional velocities

(ratioed with respect to the speed of light) by an exponential curve in which

the velocities rise rapidly towards infinity as that speed in approached. Most

measurements of z from less distant galaxies afford numbers between 0 and 1 (for

example, z = 0.1 represents a distance of about 1 billion light years). Farther

out galaxies showing redshifts of 1.2 correspond to ages in light years of about

8 billion years; HST has now observed many galaxies with z's up to 2+; distant

quasars, some about 10-11 billion l.y away, have shifts of 3 - 4 or higher (at

an observed age much earlier in Big Bang time).

As implied above, the farthest

galactic-sized objects found to date are about 13 billion l.y. from Earth . These

most distant sources yet detected have a redshift z verging on 5.8 (reaching to

about 90% of the speed of light) and represent galaxies that formed in the first

billion years or so after the Big Bang. Here is an image obtained during the Sloan

Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) showing a galaxy with a redshift of 5.82 that is unusually

bright (a quasar is inferred as the cause).

The time at which such large

sources of detectable luminosity is sometimes cited as the Friedmann time,

taken as the narrow time span when stars first formed and collected in significant

groupings. These often contain quasars that presumably grew from young (protogalactic)

gas clouds which at the time were emitting photons at an observed temperature

of ~3,000° K (referenced to an idealized blackbody - one which completely absorbs

incident radiation of all wavelengths and acts as a perfect emitter; at that temperature,

the wavelength signature peaks at ~1 µm, however, at higher z values the actual

blackbody temperatures can be much higher, causing a peak in the ultraviolet).

Recessional velocities as

a function of distance of cluster galaxies from Earth as the observational

frame of reference can be calculated from the Hubble equation and z values.

Choosing a Hubble constant that gives 14 Ga as the age of the Universe, a galaxy

recedes an additional 25 km/sec for each million l.y. further out one looks through

space. For a cluster in the Virgo Constellation, at a distance of 78 million light

years, the recessional velocity is ~ 1200 km/sec. For the Bootes cluster, at 2.5

billion l.y., the velocity has increased to 22000 km/sec. Galaxies whose distance

is about 5 billion l.y., attain velocities approximately one-third the speed of

light (100000 km/sec). The most distant observed sources (mainly quasars) reach

recessional velocities approaching light speed. The same type of velocity distribution

would be ascertained at any other observational point (such as set up by the distant

galaxy "civilization" referred to earlier) in the Universe.

As HST observations accumulate,

it is becoming evident that, with its resolving power, structure in galaxies can

still be recognized out to about 4 billion light years. Present evidence is that

beyond a z value of 2.75 no well-formed spiral galaxies can be confirmed to exist

(but at least some are likely). Those that lie farther out seem to be ellipitical

or commonly "dismorphous" (no regular form). Since these are older, this implies

that spiral galaxies may not develop until later in galactic evolution. Some of

the earlier-formed spirals have one or more extra arms compared with younger ones

(the Milky Way has 3 major ones).

The discussion in the above

paragraphs is confined to redshift measurements that can be made from observable

astronomical phenomena such as galaxies and quasars. There is another aspect

which is more theoretical, namely, the redshifts in the earlier history of the

Big Bang prior to the onset of the Decoupling Era (before which no direct observations

is possible). At the Planck Time of 10-43, the redshift z is calculated

to be 1032. After one minute - the beginning of the Radiation Era,

z drops to 109. In the first 1-2 billion years after the B.B., the

redshift decreases from about 30 to 6. The latter is near the maximum value

determined so far by direct measurements - the galaxies with that value are

about 13 billion l.y. away.

This systematic decrease

in redshift accompanies the expansion of the Universe. The process of enlarging

space leads to a lengthening of the wavelength of light - hence the progressive

drop in the redshift value of z. Since redshift also depends on the velocity

of a receding object, it follows that the maximum velocities of galaxies are

found in the outer reaches of the observable Universe. This is logical: if all

matter/energy was concentrated at a singularity at the time of the Big Bang

and then dispersed thereafter, those manifestations of matter such as the galaxies

that are farthest from the observation point (for us, Earth) must have been

traveling at the fastest speeds.

There is also another theory

which can, in principle, modify the implications of the observed redshifts, namely,

that the velocity of light is not constant but has changed over time by

gradually slowing down: this is the "tired light" concept which, while intriguing,

has so far not been supported by data or observational proofs. It has its supporters;

some cosmologists and quantum physicists have postulated that the current values

of certain fundamental parameters have changed with time, having different values

[especially in the early moments of the Big Bang] that evolve into their present

numbers as the Universe grew. Even though evidence for this is presently lacking,

this is not trivial or frivolous speculation but falls into the time-honored scientific

methodology of proposing seemingly outlandish theorems or propositions capable

of explaining some phenomena and then conducting experiments to confirm or deny

the idea.)

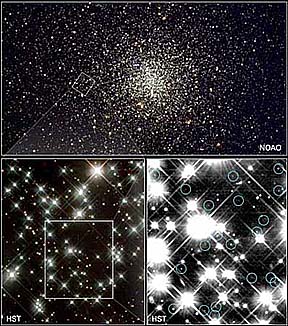

The age of the Universe

is a fundamental value which cosmologists seek with great care and effort to

establish accurately. What will help in settling on a "best value" would be

an independent measurement using a technique other than the recessional velocity

extrapolation. In April of 2002, a seemingly reliable second method has been

reported. It is based on knowledge of the time involved in white dwarf stars

burning out their remaining fuel to reach a "glowing ember" state. Theory sets

a fairly precise time span for this to occur. In the earliest stages of galaxy

formation, globular clusters will contain rapidly produced white dwarfs as large

stars burn their hydrogen over a brief time and then enter the dwarf stage.

The "embers" that are very old are hard to detect by telescopes. But, the Hubble

ST has been used on a globular cluster near the Milky Way to search for these

embers; by taking a long exposure image (8 days, spread over 67 days) these

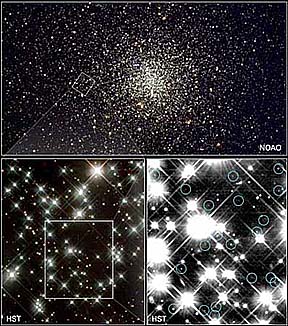

faint white dwarfs were detected, as shown in this set of images of stars within

cluster M4:

As reported by Dr.Harvey Richer

and his colleagues, calculations place the age of these white dwarf "cinders"

at between 13 and 14 billion years. By adding ~1 b.y. (typical time for the first

globular clusters to develop) to these values, this independent age assessment

falls right within the same range now generally accepted from recession measurements.

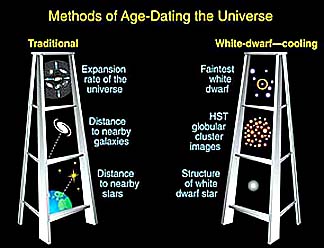

The two methods of determining Universe age, using a "ladder" approach to arrive

at the final values, are shown schematically in this diagram:

Unless fatal flaws are

discovered in either or both methods, it seems now that an upper limit of 14

billion years will stand as the actual age of our Universe.

Cosmic

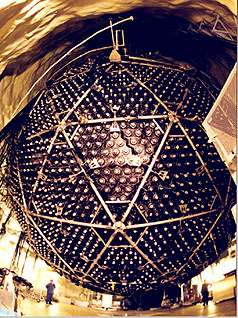

Background Radiation

Another solid proof for the

Big Bang was the discovery that Cosmic Background Radiation (CBR) peaks

near the wavelength of 1 mm (1000 µm [micrometers]) which lies at the far IR/microwave

boundary region of the EM spectrum. This is the wavelength expected from a radiant

blackbody source whose temperature is now 2.72° K. George Gamow and his colleagues

had first predicted such radiation (their estimate of its peak was at 5° K) in

1948. The CBR now evident as pervasive throughout space can be traced to an equilibrium

state between nucleons, electrons and photons that was arrived at when the Universe

had cooled to about 10 million °K at approximately 6 months after the Big Bang.

Evidence of what it was doing during the Radiation Era, up to Decoupling, is lacking

because of the opacity brought about by scattering and internal entrapment of

photons (see page 20-1) within the early Universe

during the next 300,000 years. At that time, as the temperature dropped to about

4000 °K, almost all electrons (the principal scatterers) and protons were able

to combine as hydrogen atoms that no longer scattered the photons so that light

and other radiation emerged from the radiation "fog" which was fully lifted by

1,000,000 years after the B.B. With the resultant transparent Universe, CBR first

became detectable, displaying the higher temperatures it then possessed in the

still early Universe. From Decoupling to the present time, the CBR has experienced

a redshift of ~1200.

The photon radiation now

being measured is a manifestation of the present-day Cosmic Microwave Background

(CMB), inherited from the original radiation (much hotter and therefore then

of much shorter wavelengths in the infrared) released at the Big Bang. Astronomers

commonly refer to the CMB as the general residue of photons that were produced

and released during particle interactions in the first minute of the Universe

- colloquially, the CMB is the remnant of the "burst" of radiation that marked

the "explosion" of the Universe (but which really didn't explode in the sense

of detonation of a nuclear device in which there is an initial "flash" of light).

It is also referred to as the "afterglow" of the B.B. This radiation seems to

be very uniform and isotropic throughout the Universe. The vast majority of

all photons found in the present Universe are tied up in the background radiation.

However, despite their huge numbers, it is estimated that they comprise only

about 1/50000th of the mass contained in all the galaxies. The present ~3° K

value is consistent with a predictive model that requires very energetic high

temperature radiation (mainly gamma rays, with much shorter wavelengths) that

constituted the early CMB released soon after the Big Bang to cool drastically

by adiabatic (no energy added or removed) thermodynamic expansion

(a good Earth analog: expansion of an air mass is accompanied by release of

heat with resultant cooling) within a Universe having at the least the presently

observed spatial limits. Mechanistically, as space is stretched the original

short wavelength photons experience a corresponding lengthening of their wavelengths

into the microwave region and so lose energy (E = hc/λ) which in turn is

expressed as a much lower temperature.

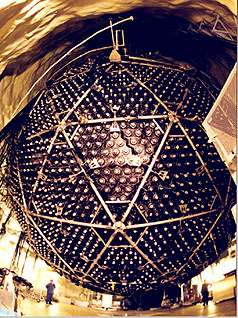

The extraction of a weak radio

telescope signal (after receiver noise was subtracted) in the microwave region

at 7.3 cm (4.1 GHz) was made in 1965 by R. Wilson and A. Penzias (for which they

received the Nobel Prize in Physics; actually, a similar signal was first detected

in 1961 by E. Ohm, then verified by B.Burke, but not connected to the CBR prediction),

with its correlation to cosmic background radiation then confirmed by R. Dicke

and his group at Princeton. This test, along with the work by Hubble, the theory

of General Relativity by Einstein, the pioneering concepts of a primordial singularity

by Lemaitre, the Inflationary Model by Guth, and supporting contributions by numerous

cosmologists, astronomers, physicists, and mathematicians, taken together, make

up the critical foundation concepts that support and explain the Big Bang in its

present form. Further discoveries will likely lead to refinements but the fundamental

concept and the proper numbers predicted from the general model now seem to be

solidly substantiated.

The value of satellites in

this refinement process is well illustrated by COBE (Cosmic Background Explorer),

launched in 1987 (check out its current Internet site).

Earlier attempts by Smoot and others to map the apparent non-variant (uniform)

background radiation over the entire sky using balloons and aircraft, to make

measurements above the atmosphere which blocks out (absorbs) radiation in the

.001 to 0.1 m region of the spectrum, gave strong hints of radiation uniformity

but were subject to imprecision. With COBE, the mapping process was greatly improved

so that a detailed chart covering the full sky was assembled in just a year. COBE

verified the high degree of uniformity of the present background in all directions

and also confirmed that the general expansion is extremely uniform in all directions.

And, COBE took extremely accurate readings over much of the wavelengths involved

in the blackbody curve determined experimentally for a 2.726° K body, demonstrating

that the background radiation fits that curve at better than 99% accuracy (an

astounding achievement seldom attained in most scientific measurements). These

measurements were then combined with those covering other wavelengths and obtained

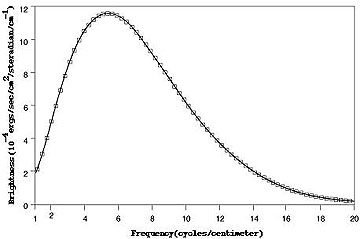

by different means to produce this classic blackbody radiation curve (see page 9-2) in which the

COBE values were so accurate that error bars could be omitted (when the COBE curve

was first displayed to participants at an Astronomy conference, the audience was

moved to give a standing ovation; such an extraordinary curve with all points

precisely on the best fit version is the dream of all experimental scientists).

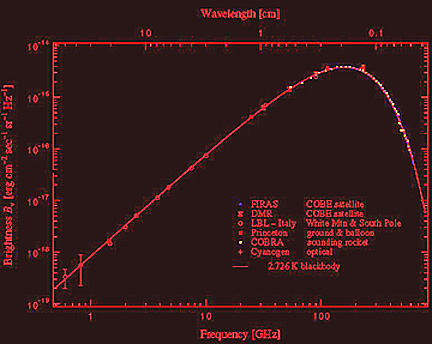

A variant of this includes

measurements made by other CMR measuring experiments (different systems).

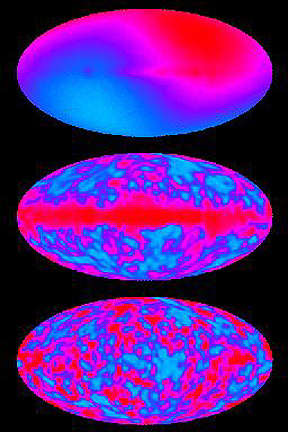

COBE also allowed the mapping

of radiation in the early stages of the Universe (specifically, at the close

of the Radiation Era some 300,000 (perhaps to 500,000) years after the Big Bang,

when the plasma in the expanding Universe had cooled sufficiently to become

transparent to photons) to an accuracy such that it showed variations in temperature

and density as slight as 1 part in 100000 during the first billion years after

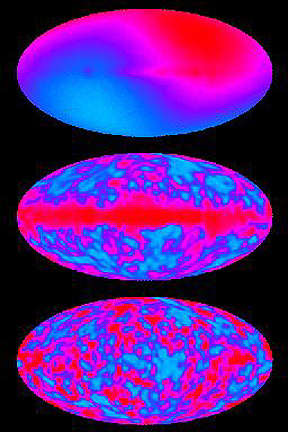

time zero. The maps below show the broad distribution of minute temperature

differences across the early Universe as detected by COBE's DMR (Differential

Microwave Radiometer) using data collected at 53 and 90 GHz. The blues represent

slightly cooler and reds slightly warmer temperatures - thus also define regions

of greater and lesser densities.

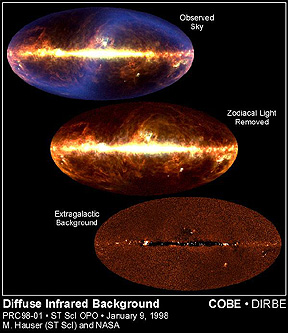

The top map is the "raw"

data plot in which the dipole effect caused by the Doppler motion of the Milky

Way galaxy has not been removed. The middle map results when the dipole effect

is eliminated, but the radiation from the Milky Way (central band) has not been

compensated for. The bottom map is the final product with both dipole and galaxy

effects removed - this is the one usually cited as the model for CMB distribution.

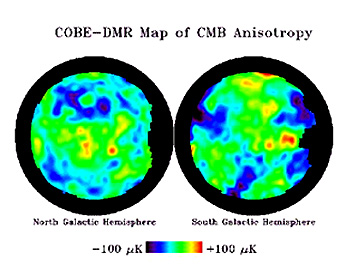

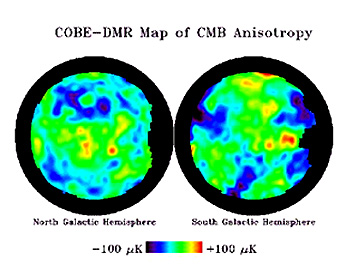

Another such plot, using different colors, recasts the distribution in terms

of the northern and southern hemispheres of the celestial sphere:

These small differences were,

however, vital in allowing matter to break from the initial extreme uniformity

into regions of slightly cooler, denser conditions where the protogalaxies could

begin to form. Eventually, in the early Universe these seed fluctuations promoted

localized clotting of particles that became gravitational centers whose growing

attraction of more matter led ultimately to development of the billions of galaxies

that populate the Cosmos as we now know it.

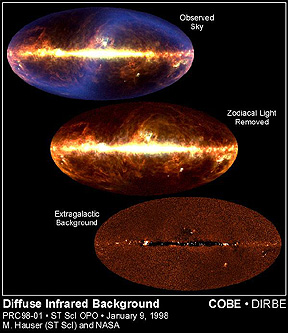

COBE has allowed an estimate

of the total energy in the Universe by sampling yet another part of the spectrum.

This results from painstaking analysis of radiation in the far infrared using

the Diffuse Infrared Background Experiment instrument onboard. This measures heating

of the dust distributed throughout the Universe, using windows at 140 and 240

µm. However, the overall background is "contaminated" by dust and other sources

within and around the Milky Way, the Earth's atmosphere, and other sources, which

require correction. The procedure is indicated in this figure:

The upper panel shows a sky

map of the infrared radiation for the whole Universe with a bright central band

representing the Milky Way contribution. The central projection is the change

after Zodiacal light is removed. The bottom panel is the residual infrared radiation

for the Universe after the Milky Way Galaxy's influence has been removed. The

net effect is that there is much more starlight in the Universe as "fossil radiation"

than heretofore suspected owing to the masking by dust (ranging from near-Earth

to intergalactic) whose influence is now accounted for with this corrective DIRBE

inventory.

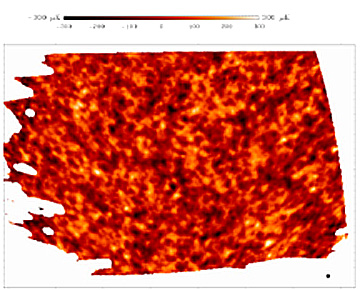

In April, 2000 a group of

scientists presented the results of project BOOMERANG (acronym for Balloon Observations

of Multimetric Extragalactic Radiation and Geophysics) One output was a more detailed

map of 3% of the sky which shows variations (with a 35x improvement in resolution)

in CBR at the end of the Radiation Era - which also signals the beginning of the

Decoupling Era marked by the recombination of protons and electrons to form hydrogen

atoms. This map was constructed by measurements obtained with a passive microwave

telescope suspended on a balloon for 11 days at approximately 36400 meters (120,000

ft) above the Earth's atmosphere over the Antarctic. The variations depicted are

in units of microKelvins.

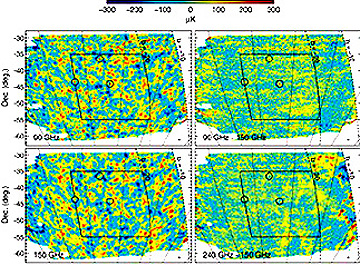

Here are several more maps

from this experiment using radiation detected at different wavelengths. The

upper and lower left maps are at 90 and 150 MHz respectively; the two right

maps are differences between 90 - 150 (top) and 150 - 240 (bottom) MHz.

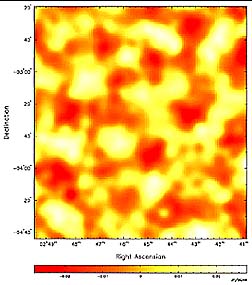

These results are confirmed,

with more detail, by the CBI (Cosmic Background Interferometry) experiment run

jointly by CalTech and the NSF. Thirteen 1 meter diameter dish antennae are

synchronized in an array with a broad baseline. This next figure is a map of

the background radiation over an area equivalent to about 2 widths of a full

Moon. The differences being measured are temperature values in microKelvins

(µK) that vary around the mean sky temperature of 2.73 K.

What is being sensed are

small temperature differences when the CBR was around 6000° K. Associated with

these differences are variations in material density. This observation supports

the idea that matter in the Universe at this early time was unevenly distributed,

thus allowing the first stages of density/gravity variations required to initiate

the galaxy formation process. The data displayed in these maps also bear on

the model that predicts the Universe had undergone a dramatic Inflation in its

initial moments, and in effect provide a positive test of that concept. They

likewise point to the notion of a flat Universe that will expand forever (see

below).

A recent announcement from

Hubble scientists carries this cosmic background concept into the visible radiation

realm. Based on estimates of quasar populations at the farthest reaches of observable

space (the Deep Field region), extrapolations of visible light sources to the

entire Universe can be made. Results suggest that most of these sources are now

accounted for and that the total amount of visible light which persists throughout

the Universe is approximately of the order to be expected (by calculation) from

the same model that predicts the amount of Cosmic Background Radiation. In other

words, as different parts of the EM spectrum are analyzed for total energy involved,

the numbers remain consistent with expectations and thus support the energy distribution

predicted from the Big Bang model. The overall notion of an expansion appears

on firm ground based on the ever accumulating scientific evidence.

The results from COBE proved

of such import to understanding the early Universe, especially the small but critical

fluctuations it detected, that a more sophisticated satellite, MAP (Microwave

Anisotropy Probe), was launched in July of 2001. Background information on this

important new astronomical observatory can be found at NASA Goddard's MAP

site. (Another CBR satellite, the Planck Surveyor, is planned for launch no earlier

than 2005.)

The long-awaited preliminary

results from MAP were announced at a press conference on February 11, 2003.

Prior to that MAP was renamed WMAP, honoring David Wilkenson, a leader in the

field.

The higher resolution of

WMAP, in terms of ability to measure even smaller temperature variations, is

evident by comparing the new all-skies thermal map from WMAP with the equivalent

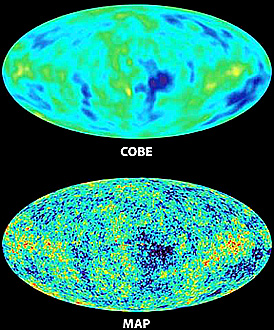

coverage by COBE:

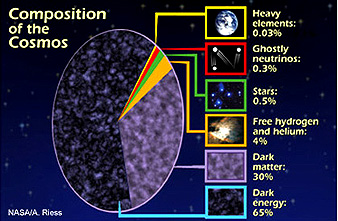

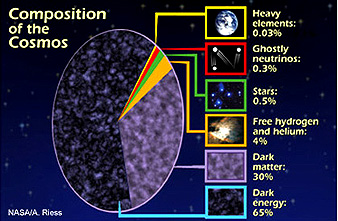

Some very far-reaching

conclusions about the Universe have been drawn from interpretations of the WMAP

data. One is a new (but still not necessarily the most accurate, although an

accuracy of +/- 1% is claimed) age for the Universe of 13.7 billion years. Another

is strong confirmation of the reality of Inflation during the first fraction

of a second after the Big Bang. The amount of detectable ordinary matter in

the Universe has been reset at 4% whereas dark matter is 23% and dark energy

73% (but the results offer no clear indication of the nature of these dark states).

The time when the Universe first became transparent is now given as 380000 years

after the B.B. Further evidence for accelerating expansion is derivable from

the data, leading to a firm conclusion that the Universe should expand forever.

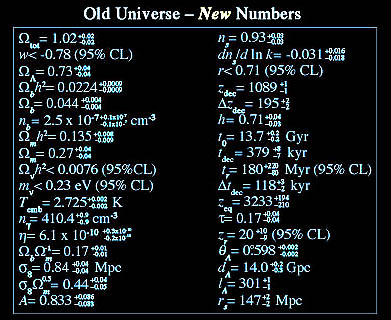

Finally, many of the fundamental physics and cosmological parameters have been

refined, as shown in this table (without any attempt by the writer to identify

each).

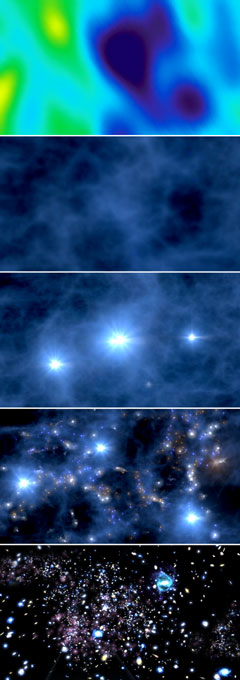

Some of the recent ideas

on the start times for the first stars and galaxies received support and specificity

from the WMAP results. The first stars began to form as Supergiants about 200,000,000

million years ago. The first galaxies began to organize some 300,000,000 million

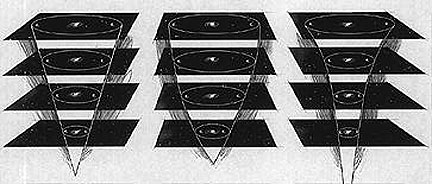

years later. This diagram depicts these stages (from top): 1) initial stages

of CBR variations; 2) clots of dark matter prior to organization as stars; 3)

the first supergiants; 4) developing galaxies; 5) galaxies after the first billion

years.

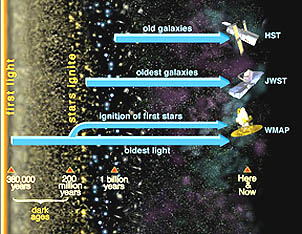

The time lines for the

first stars and galaxies as measured by different space telescopes (JWST is

the James Webb Space Telescope planned for 2010) are shown in this diagram

Some cosmologists attending

the press conference went on record as believing the WMAP results will prove

to be the most important new data sets obtained from observations over the last

decade.

A major future objective of

WMAP still to be addressed is to measure extremely small temperature fluctuations

that should support/confirm the existence of gravitational waves. These were first

postulated by Einstein as a consequence of his General Theory of Relativity. Gravitational

waves represent moving disturbances within gravitational fields that are generated

by various interactions of matter and/or energy, such as collisions of black holes

or neutron stars. With their force particles, the gravitons, they are analogous

to electromagnetic waves, with their photons, except that gravitational waves

can move unimpeded through matter that itself interacts with photons by absorption.

Like the graviton, gravitational waves have yet to be detected but their behavior

and influence within the Universe can be simulated with computer-based models.

As gravitational waves move through space, they cause the geometry of space to

oscillate (stretching and squeezing it). The wavelength of a gravitational wave

depends on the mechanism of its generation.

Theory holds that gravitons

and gravitational waves were first created during the Inflation period between

10-38 and 10-35 seconds at the outset of the Big Bang.

These waves participated in the extreme expansion of those moments and as a

result their wavelengths were greatly elongated. The inflationary gravitational

waves played a key role in bringing about the slight variations in the distribution

of matter and energy during the Radiation Era which ended in the Decoupling

Era at which time photons were no longer scattered - this latter period is the

earliest in which Cosmic Background Radiation could then be detected. WMAP will

seek to determine more exactly the temperature fluctuations in the CBR field

which correspond to the pertubations imposed by the gravitational waves. In

theory, these waves are detectable by analysis of the CBR coming from the Cosmic

Microwave Background; gravitational waves will cause the radiation to be right

or left polarized whereas density variations in the CMB will induce radial polarization

(the two modes of polarization must be separated and distinguished by Fourier

analysis.

Models for the Expanding

Universe

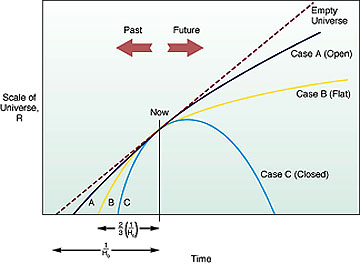

Models of the Universe can

be classified in several ways: 1) Newtonian vs Relativistic; 2) with or without

a Big Bang, i.e, expanding vs steady state; and 3) for the Big Bang models, these

are either Standard or with a Cosmological Constant.

As a fundamental conclusion

drawn from the general acceptance of the Big Bang model for the Universe's origin

and development, the initial small space developed in the first minute has been

continuously enlarging - a process analogous to expanding in the manner described

on the previous page. However, the precise nature of this expansion, still not

fully known, depends on the specific expansion model, as we shall see below.

This is related to the amount of mass/energy available to control or influenced

the expansion. As we will see in the following paragraphs, proposed geometries

of the expanding Universe range from spherical to hyperbolic to flat. The duration

of expansion ranges from finite to infinite. The terms "open, closed, flat"

refer to certain constraints on the curvature of space and on its expansion

history.

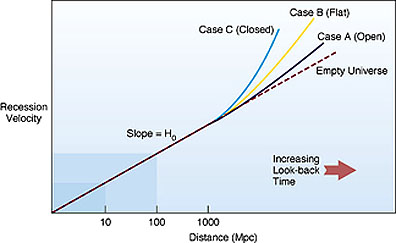

The type of Universe "shape"

model - open, closed, flat - is a factor in the change in the Hubble constant

(and the corresponding redshift) with time. A generalized relationship depending

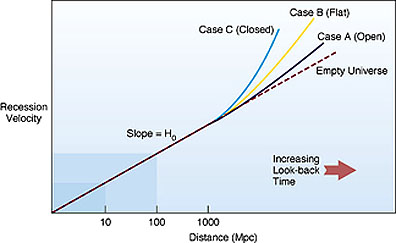

on expansion models is shown in this next plot:

Before reviewing the various

models that were proposed in the 20th Century, we pause to briefly describe

a useful and (deceptively) simple view of the Universe embodied in the term

Hubble Sphere. This is based on the idea underlying the Hubble Length,

which is just the distance outward from Earth, as an arbitrary center

(remember, the Universe actually has no meaningful center), that has traveled

in 1 Hubble time (tH = 1/H). In this framework, that distance is

represented as the farthest out we can look from Earth with our best telescopes

to see the first evidence of the Big Bang (which is not really possible owing

to the opacity soon after the B.B.); it is closely related to lookback time,

defined above. Consider the Hubble distance to be the radius r for a sphere

that encloses all of the Universe that we can presently see (this seems legitimate

in that currently the farthest galaxies [only a few found so far] all seem to

be about the same distance in light years from our observation point; these

distances are somewhat less that the outer limit that is defined by the current

value of H0). A simple way to visualize this sphere with its contents

is to imagine the points within (galaxies) such that the farthest away (representing

star systems in their earliest years are colored blue, intermediate green, and

closest (more advanced in development [but not necessarily any older or younger

than the blue group]) as red. The occupants of the Hubble Sphere would thus

show concentric color bands with blue closest to the sphere boundary and red

closest to the center. That boundary is, of course, a time horizon and

not an actual physical surface encompassing the sphere. As we progress into

the future and our instruments "see" still farther, the apparent surface of

the sphere moves outward with the increase in rH. There are galaxies

beyond the Hubble Sphere; they just haven't been seen yet but will come into

view later. Beyond the outermost galaxies, assuming they occur at light year

distances equivalent to that of a precisely known Hubble Age, we cannot as of

now specify "What's there".

Using this simplified,

rather easily visualized model, let us take a moment to say a few things about

the size of the known Universe. It would seem to be determined by the

Hubble Distance (DH), which relates to the Hubble Age, around 14

billion years. This is the distance out to the event horizon, the farthest

out in spacetime that we can see discrete particles or objects in the Universe

(To quantify the distance in Earth kilometers [or miles], just multiply the

distance that light travels in 14 billion years by the speed of light. Thus:

14,000,000,000 b.y. x 300 x 104 km/sec x 3600 sec/hour x 24/hrs/day

x 365.4 days/year. For this case, the result, which I will call DH,

is 1.3245 x 1024 km, or about 1.3245 septillion kilometers.) From

the Hubble Sphere model, one might assume that the sphere has a diameter of

2 x DH, particularly when one is aware that the event horizon is

essentially the same looking outward, say from the North Pole at the northern

celestial sphere and from the South Pole at the southern celestial sphere. But,

this is no so. In relativistic space expansion, the distances outward in opposite

directions from the Earth framework are not additive. This is due to the fact

that all point in the singularity that are now galaxies were next to each other

at the beginning and have simply drawn apart with the expansion of space. With

no meaningful center, we can only state for now that space has expanded so much

in 14 billion years. Euclidian size is not a valid way to look at the Universe,

whatever "shape" it may have, as implied from the paragraphs further on this

page. In trying to think about "size" there is a further complication. The expansion

during the Inflation period (see page 20-1) may have proceeded at rates faster

than the speed of light. If so, the Universe may really be much bigger than

what we deduce from event horizon distances. We get our idea of distances only

from measurements of z and H as determined from we see now in the Universe after

the galaxies formed. Prior to those times, inflation expansion, yielding much

greater z and H values, could have pushed the outer edge of the Universe to

distances well beyond what can be detected as apparent event horizons.

So, what can we say about

our understanding of the size of the (our) Universe. Its minimum size must be

at least as far out in spacetime as we can see galaxies, quasars, and supernovae

- 13+ billion light years to the currently known event horizon. (We cannot [yet]

see timewise to anything before the Radiation Era; Cosmic Background Radiation,

which traces to about 300,000 years, is pervasive and thus not location-specific.)

The maximum conceivable size is infinity, with "outer limits" reachable only

in infinite time. If the Universe is indeed infinite, its present outer limits

are not fixed in any way, as they will enlarge forever in their expansion towards

infinity. If the Universe is proved to be finite (contrary to the most likely

scenario - see below), then its boundary is almost certainly beyond the event

horizon we now see - there are more galaxies farther away which will become

visible as time progresses and DH lengthens.

Now, to survey the major models

for the spacetime Universe:

Relativity has played a vital

part in the models of the Universe that remain the most plausible. The expansion

of the Universe from a relativistic framework can be summarized as the Friedmann

equation. We give it here in two forms, the first as a differential equation:

dR/dt = (8 Π G)/3

ρ R2 - kc2

And the second:

H2 - (8 Π)/3

G ρ= - kR2

In these equations, Π

(pi) is the familiar constant (ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter

= 3.14159...), G is the universal Gravitational constant, ρ is a Greek letter

denoting the average density of the Universe, k is a curvature constant in which

values of 0, +1, -1 represent flat, spherical, and hyperbolic geometries respectively,

R is the Scale Factor for the observable Universe, H is the Hubble Constant, c

is the speed of light, and t is time. A solution to the Friedmann equation depends

on which Universe model is being tested, as the group described next has different

values for key parameters.

Several cosmological scenarios,

named after the scientist(s) who first proposed each (several scientists came

up with more than one model), for various modes of expansion lead to different

end results (shown graphically below for four general models).

In common, they all obey

the Cosmological Principle, which states that the Universe is both homogeneous

and isotropic (essentially the same average distribution of matter/energy

in all directions) on the largest scales (this is not violated at the

scale of galaxy clustering since at the universal scale these tend to be "smoothed

out" by having much the same patterns anywhere one looks). Open models also

must be consistent with the restriction placed by the Second Law of Thermodynamics

which from a cosmological standpoint states that over time the entropy

(a measure of disorder of a system) must ultimately increase to (or towards)

a maximum (total disorder); interpreted at a universal scale this would lead

to complete dispersal of galaxies and their stars (perhaps rearranged as randomly

distributed Black Holes) and blackbody temperatures approaching zero. A corollary

holds the initial singularity to have minimum entropy which then rapidly increases

during the first moments of the Big Bang.

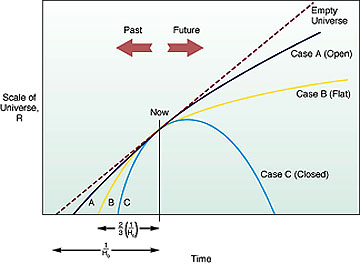

Note that when the above curves

are extrapolated back in time, they strike the horizontal axis at different positions

(times). This means that the age of the Universe will vary relative to the particular

model being considered. Thus, although the current Hubble time (1/H0,

which depends on the accurate determination of the rate of expansion) leads to

an age or duration of the Universe, that value can be modified when (and if) a

particular expansion model is shown to be the best or valid one.

The following table (modified

from Hawley and Holcomb, 1998) summarizes the principal Cosmological Models that

have been developed and tested by calculations. They fall into two groups: Non-Big

Bang (B.B.) and Big Bang. Another distinction category: Models in which the Cosmological

Constant L (see below) is a factor (upper five rows of table and the Standard

Friedmann (or Friedmann-LeMaitre) models in which L is not involved (i.e., is

O; bottom three rows); the three standard models also have Deceleration Parameters

q (defined below) that include the value 1/2 in some way.

|

MODEL

|

GEOMETRY (k)

|

L

|

q

|

FATE

|

| de Sitter |

Flat (0) |

>0 |

-1 |

No B.B.; exponential expansion; empty |

| Steady State |

Flat (0) |

>0 |

-1 |

No B.B.; uniform expansion |

| Einstein |

Spherical (+1) |

Lc |

0 |

Static; H = 0; now, gravity balanced by repulsive force; may be unstable

|

| Lemaitre |

Spherical (+1) |

>Lc |

<0 |

Expand; hover; expand |

| Negative L |

Any |

<0 |

>0 |

Big Crunch |

| Closed |

Spherical (+1) |

0 |

>½ |

Big Crunch |

| Einstein-de Sitter |

Flat (0) |

0 |

½ |

Expands forever; density at critical value |

| Open |

Hyperbolic (-1) |

0 |

0<q<½ |

Expands forever |

q = The Deceleration Parameter:

denotes the rate of change with time of the Hubble Constant and R; a positive

value indicates acceleration; negative = deceleration.

L = The Cosmological Constant,

introduced by Einstein to his field equations for General Relativity in order

to provide some constraint to gravity (a counter-effect) to avoid an inevitable

collapse of the Universe; if + (repulsive) L counteracts gravity; if - (attractive)

L augments gravity. Lc is one particular number known as the critical

value. L may be equivalent to the vacuum energy density associated with particles

at the quantum level. (L in texts is also given by a capital Greek letter Λ).

The Steady State, de Sitter,

and Einstein Universes, all non-standard, are currently not supported by observational

evidence.

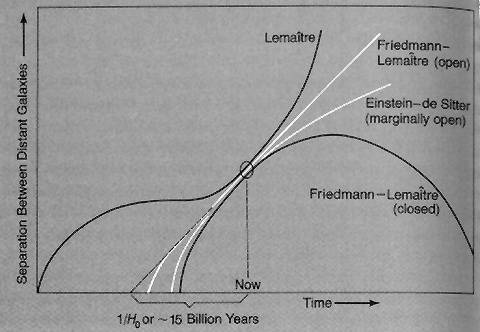

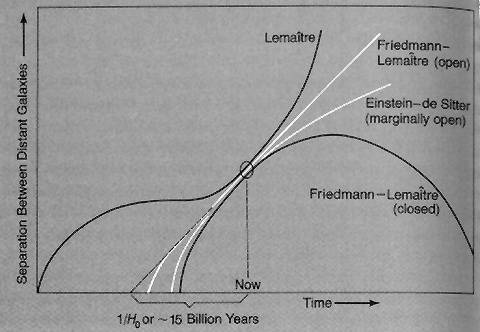

The more general diagram

above showing four alternative expansion models can now be redisplayed in terms

of some of the specific models described in the above table:

From J. Silk, The Big Bang,

2nd Ed., © 1989. Reproduced by permission of W.H. Freeman Co., New York

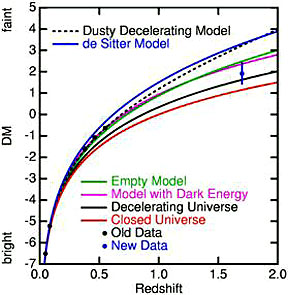

This next plot is a recent

display of the curves for various models in which the ordinate is the relative

brightness (luminosity) of galaxies used as data points. (The dark energy case

is discussed on the next page).

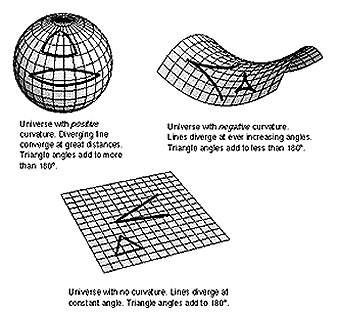

The nature and shape of the

Universe depends on its mass density (including energy forms that have mass).

The key parameter is the Critical Density, symbolized as ρc

(ρc = 3H3/πG). This is defined as just that total

mass that causes the Universe neither to expand forever nor to collapse on itself,

i.e., it is flat and will just stop expansion after infinite cosmic time has elapsed.

(As a practical measure it is estimated that, if all atomic matter - both galactic

and intergalactic - is redistributed to spread uniformly through space, its density

will average 10 atoms per cubic meter.)

There are three general

shapes available as options for the configuration and expansion of the Universe.

Their geometric characteristics are depicted in this next figure. Note that

two properties help to define the nature and behavior of each shape: 1) What

happens to so-called parallel lines in traversing the shape, and 2) What is

the sum of angles in any triangle drawn on the shape?

The spherical shape is

said to have no boundary in that one would always remain on its surface and

if "walking" along a great circle would always return to the starting point.