Exploring the planets with

spacecraft began with the first trip to the Moon, two years after the former

Soviet Union set the space program into full motion with the launch of Sputnik

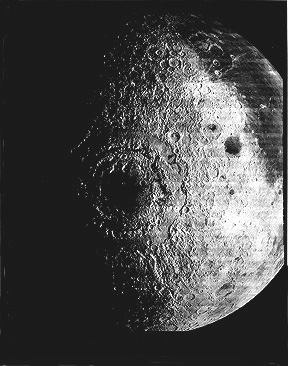

I, in October 1957. In September 1959, Lunik (Luna) 2 impacted onto the lunar

equator. The next month Luna 3 completed the first flyby of a planetary body,

returning a series of pictures of the lunar limb and a few views of the Moon's

farside, neverbefore seen by humans.

All told, the Soviet lunar

program sent 20 Luna spacecraft and 5 Zond craft to the Moon; most but not all

were successful. Several reached the lunar surface. Lunokhod 1 was the first unmanned

roving vehicle to operate on another planetary body, landing on November 17, 1970.

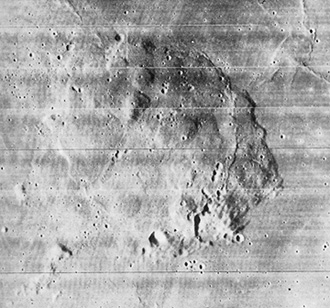

The first U.S. missions

to the Moon were literally a crash program! Between 1961 and 1965, NASA

launched three Ranger spacecraft like bullets to land (impact) onto the surface,

destroying themselves in the process. Each Ranger had a television camera mounted

in its nose that looked forward at the surface as it approached. They instantly

telemetered progressively higher resolution images, until the moment of collision.

The last images had resolutions of just a few meters. Here is a typical example,

captured by the Ranger 7 camera. Each trapezoid frames the next scene in the

succession:

One of the hallmarks of pre-Apollo lunar exploration was the Lunar Orbiter

program, in which five "photolab" spacecraft orbited the Moon between August

1966 and August 1967. The former Soviet Union was actually the first to orbit

the Moon, in April of 1966, but its image returns were minimal. The first

three Lunar Orbiters used orbits inclined to the equator, and the last two

were in near-polar orbits. Each had a payload consisting of two cameras holding

70 mm black and white film. One camera, with a wide angle lens, produced photos

whose resolutions ranged from 8 m to 150 m (26 ft to 492 ft) depending on

varying orbital altitudes. The second High Resolution camera improved these

values by a factor of eight but covered much smaller areas. The photos, developed

onboard as negatives, consisted of continuous strips, electronically scanned

by a "flying spot" passed into a photomultiplier tube that generated an analog

signal transmitted to Earth. On Earth, the signal drove an imaging device

which produced 35 mm positive strips that photointerpreters joined into mosaics.

The 2,000, or so, photos from these missions covered almost the entire lunar

surface, leading to detailed geological maps that have been interpreted mainly

through superposition and cross-cutting relationships (see next page). Here

are four typical scenes:

In the top left is an oblique view of the Apennine Mountains, with an uplifted crust that is similar to highlands in terrain characteristics, lapped by mare lavas from younger basalts that filled Oceanus Procellarum. The right photo above shows lava plains with sinuous rilles (flow trenches) in Oceanus Procellarum and part of crater Prinz. Each strip in the mosaic is 4 km (2.5 mi) wide.

The bottom left photo shows mare ridges (squeeze-ups) and another rille. The photo at the bottom (the fourth one) seemingly is a bland view of a flat mare surface, except that a close look discloses an upper flow unit that is marked by a distinct front that creates a lobe marking the advance. These structures clearly signify basin-filling by multiple extrusions.

19-9: Speculate on plausible origin(s) of mare ridges and sinuous rilles. ANSWER

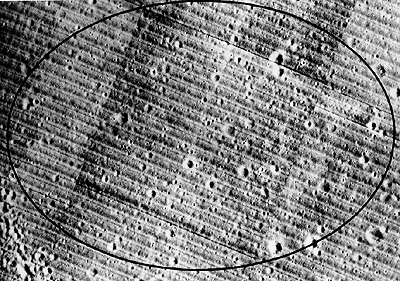

A primary goal for the Orbiters was high resolution photos of candidate landing sites. The scene below (5 km by 8 km, 3 mi by 5 mi) documents an elliptical site in Oceanus Procellarum, near the Apollo 12 touchdown point, considered acceptable despite a seemingly high crater density.

19-10: Would you feel comfortable trying to land the Lunar Module ( LM ['Lem']) in this particular site? ANSWER

Constructed from photo strips acquired by Lunar Orbiter IV, at an average altitude of 2,700 km (1,678 mi), the next classic image shows the great lunar "bullseye," known as the Orientale Basin, a multiringed (perhaps four; the outermost with a diameter of 900 km [559 mi]) impact structure invaded by lavas (Mare Orientale). This feature lies just beyond the visible western limb of the Moon; the western Oceanus Procellarum is at the upper right.

19-11: In what one way is the Orientale impact basin unlike any impact structures known on Earth? ANSWER

The Orbiters confirmed that

impact cratering is a (perhaps "the") dominant process operating at the lunar

surface. This next image is actually a photograph made by an astronaut from a

spacecraft orbiting the Moon. This is a classic young smaller crater, with an

intact rim and well-preserved ejecta beyond it.

But, signs of volcanism

were ubiquitous: photointerpreters indentified some volcanic calderas, lunar

rilles were either flow channels or collapsed lava tubes, domes were evident,

and the floors of many large impact craters contained clear indications of volcanism.

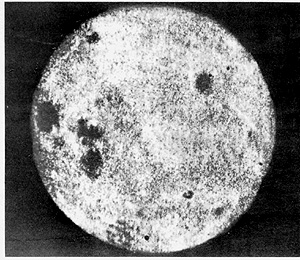

This Orbiter V view of

the interior of Tycho (see previous page; one fullmoon image shows a dark interior,

the similar image below it has a bright interior, resulting from the method

of photo processing) shows, on a larger scale, many features similar to those

on terrestrial caldera floors:

This Orbiter V close-up

view of the interior of Tycho shows details of volcanic structures such as tumuli

and squeeze-ups much like those on terrestrial caldera floors. The lavas that

enter the crater form in the lunar subcrust after the impact unloads rock from

above causing hot rock below to melt and migrate to the new crater floor (much

like blood flows to a surface wound):

19-12:

There is one conspicuous volcanic feature on the floor of Tycho.

Describe it in general terms. What is its origin? ANSWER

Constructive volcanic features

are rare. Stratocones have not been found. A few domes, such as the individuals

found in the Marius Hills or the domes atop a single larger dome at the Rumker

Hills (shown below), are characteristic of upwellings of basaltic lavas.