Asteroids and Comets

A very large number of

small (less than 1500 km maximum dimension) bodies composed of rock/dust, ice

and condensed gases orbit around the Sun as asteroids and comets.

The asteroids are composed mainly of rock, with some ice, and are detectable

by solar light reflected from their low albedo surfaces. The comets generally

are dominantly ice with some rocky material that are visible because solar light

reflects from an envelope of gases collected around an ice/rock nucleus.

Three good overviews of asteroids

and comets are found at these sites: (1),

(2),

and (3).

About 7000 asteroids have

been discovered as individuals so far (some astronomers have estimated a total

of at least 400,000 larger than 1 km exist within the solar system; the total

number, including small ones is likely well in excess of a million). More being

found each year owing to a stepped-up search program (see below). The number of

known comets is smaller.

Interest has always been high

regarding comets, balls of ice and rock, because of their spectacular appearances

(glowing "stars" with tails); they are well represented in mythologies and astrologers

portents. In the 20th Century, the asteroids, solid fragments of varying

size that orbit in several regions of the inner solar system, have had dramatic

increases in interest, in part because they are the more frequent bodies that

have collided with the Earth and the Moon, and most other larger solar bodies,

producing impact craters which on our planet could have (and have had) diastrous

consequences - castastrophic in terms of effect on life - of magnitudes only now

being properly appreciated. We will start this review with the nature and distribution

of asteroids.

About 7000 asteroids have

been discovered as individuals so far (some astronomers have estimated a total

of at least 400,000 larger than 1 km exist within the solar system; the total

number, including small ones is likely well in excess of a million). More being

found each year owing to a stepped-up search program (see below). The number

of known comets is smaller.

Tens of thousands of asteroids

occupy the Main Belt, an interval of mean distance 2.4 A.U., between Mars and

Jupiter. Telescopic observations have indicated that about 75% of the asteroids

have very low albedos, which is consistent with compositions that are similar

to carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, postulated as the most primitive solar system

material. Other (about 17%) asteroid groups occur in different locations, such

as the Apollo belt (Earth-crossing) and Trojan belt (Jupiter-crossing). Many of

the Trojan's are darker and redder. As they orbit the Sun, they also rotate, some

with periods of a few days to a week or so and others in a matter of hours ("tumble").

Comets are easier to detect

than smaller asteroids. They have higher albedos, and thus are brighter, and as

they enter the region of the Solar System within the outer planets they develop

luminous tails. Asteroids, on the other hand, present greater difficulties in

finding them and determining their orbits. Most asteroids have such low albedos

that they don't begin to reflect enough sunlight until relatively close to Earth.

Only the larger ones in the Main Asteroid Belt are fairly easy to spot and measure.

To illustrate detection techniques, let us describe how the Near Earth Asteroids

(NEA), the Apollo belt, are found and monitored to determine their size and orbits.

Optical telescopes, with

mirrors around a meter in diameter, are the instruments most commonly used.

A portion of the sky (usually around 1 to 10 Moon diameters in width) is viewed

over a short time interval (minutes to a few hours). Successive views are recorded

on film or electronically using CCDs. Stars and galaxies will retain their fixed

positions relative to each other during the interval. An asteroid will look

much like these fixed distant stellar/galactic bodies if it is close enough

to "shine". But being very close with respect to the distant background, it

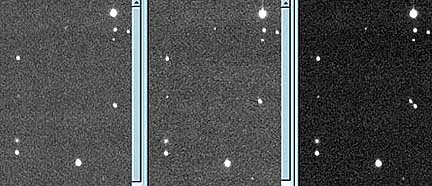

can move a measurable distance in that time. Consider this trio of telescope

photos:

In the left and center

photos, all the starlike objects appear to be in the same fixed positions. But

one such body, in right center, actually moves to a slightly new position, towards

the upper left, in the middle photo. When the two photos are superimposed, as

shown in the right image, two "stars" appear instead of one. The left "star"

in the pair is just the same body that has moved in this time interval (30 minutes).

This is explained by assuming the body is so close to the Earth that its motion

is discernible over short time periods. The presumption is that it is an asteroid.

Working with that idea, the actual distance of the object from Earth is determined

by parallax (using two telescopes). Once that has been calculated, the size

of the body can be estimated (taking its albedo into account) and its velocity

is likewise determined from the distance/time relation. Repeated observations

allow its orbital parameters to be specified.

The Earth-crossing asteroids

all are less than 10 km in maximum dimension. From actual counts, plus extrapolations,

the number of Earth-crossing asteroids greater than 1 km in diameter is now

placed between 700 and 1000; a collision with Earth for one of that size is

estimated to be around 1 per 1-2 million years and for a 10 km asteroid once

every 100 million years. The majority of all asteroids have irregular shapes.

Among the Main Belt asteroids

the biggest is Ceres (933 km [583 miles]); second in size is Pallas (530 km [331

miles) and Vesta is slightly smaller; these all reside in the Main Belt. The larger

asteroids tend to approach spherical in shape. At least some of these have melted

and differentiated, so that they have developed iron-rich cores, and possibly

a mantle with dispersed metallic iron (the pallasite meteorites may derive from

this). One school of planetologists considers these to be "small planets".

Asteroids have been imaged

by conventional telescopes, by radar, and by passing or orbiting space probes.

This first image shows that ground telescopes do not normally produce good images,

even of the larger asteroids, such as Ceres.

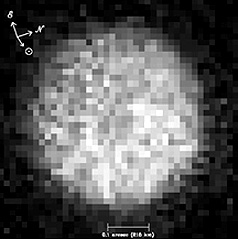

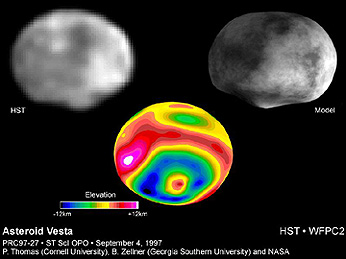

Vesta, at 525 km (325 miles),

has been imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope, as seen here:

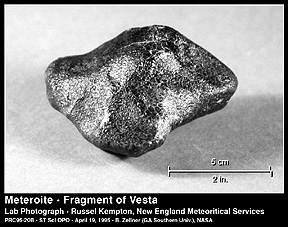

Although not shown clearly,

there appears to be a large impact crater with a central peak on Vesta. Spectral

analysis of light from Vesta produces values that are very close to the mineral

group of pyroxenes. In 1960, a meteorite was found in Western Australia that

is entirely pyroxenite (making this a rare type). Many asteroid specialists

believe this came from Vesta; if so, it is our first sample of an asteroid that

we can analyze.

Both ground telescope and

even HST images of small objects such as asteroids are blurry. Thus, to effectively

image in detail an asteroid a space probe needs to visit its vicinity.

The Galileo spacecraft was programmed to transit close to two asteroids. It

passed the first, Gaspra, in 1991. This asteroid, 19 x 12 x 11 km (~12 x 7.5

x 7 mi) in size, consists of iron-nickel and iron-magnesium-rich silicates.

This is how it appears in color:

Galileo approached and

imaged the second asteroid, Ida, on August 28, 1993, as shown here (at about

33 m [108 ft]) resolution:

This asteroid, about 58

km x 23 km (36 mi x 14 mi) in dimensions, is chondritic and, like Ida, pockmarked

with craters. Totally unexpected was the presence of a small orbiting body,

about 1.5 km by 1.2 km (0.93 mi x 0.75 mi), named Dactyl–making this pair

the first known binary asteroids. Close-up, Dactyl has a small crater, making

it look a bit like Saturn's Mimas in miniature:

The first visit exclusively

to the asteroid belt has been made by NEAR, for Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous

mission, launched in June 1997 to reach the large asteroid Eros in January,

1999. (After launch, the spacecraft had the name Shoemaker added to it, in memory

of the Dean of Astrogeologists, Dr. Eugene M. Shoemaker [see bottom of next

page]). Enroute NEAR-Shoemaker took a close look at Mathilde (59 x 47 km) as

seen here:

NEAR has successfully orbited

Eros and has begun to take data on its composition. Below is a view of Eros,

whose dimensions of 33 x 13 x 13 km give it a peanut-like shape. Eros is rapidly

rotating, as evident from the different positions over a short time span on

a December 1998 date.

NEAR has operated successfully

around EROS for two years, taking thousands of images at various resolutions from

different orbital heights. This next image is one of the best, taken in a false

color mode in which a green and two NIR bands are used.

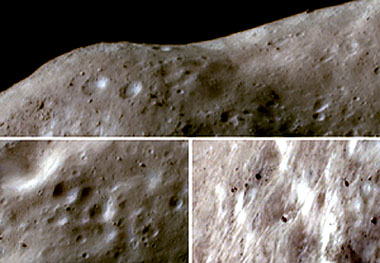

Here are three views of

parts of EROS:

Here is a close-up (resolution:

just a few meters) of a crater on Eros:

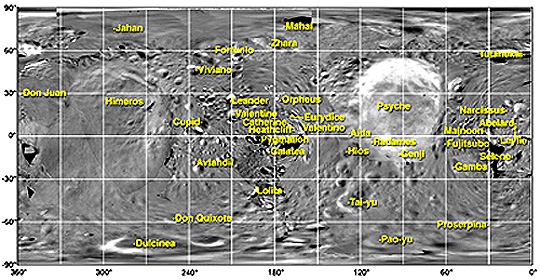

After completion of the

NEAR mission, the mappers gave names to the major features on a flattened mosaic

of its surface, as follows:

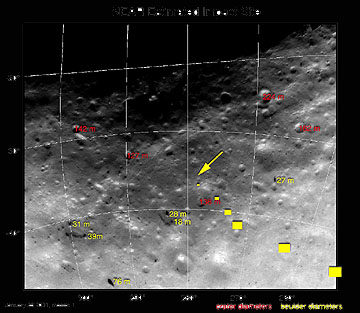

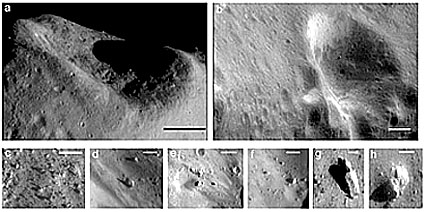

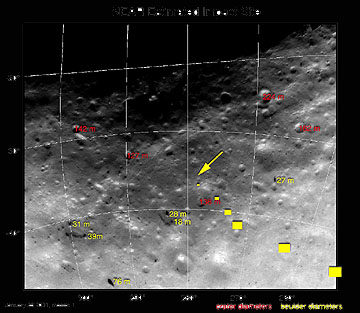

NEAR Shoemaker made a close

approach to EROS, reaching an altitude just 6 km (4 miles) above its surface,

on October 27, 2000. Here is part of a mosaic of images made during that pass.

This view shows a crater and rock debris as small as 1 meter across:

In early 2001, it was evident

that the spacecraft's fuel was nearly depleted. The NEAR scientists and managers

pondered how to finish the mission and decided on a bold course - to land the

spacecraft on EROS's surface. The asteroid was 196,000 miles from Earth; if

successfull this would be the farthest any manmade object had set down on a

solid body in the Solar System. Good operational maneuvering and some real luck

were essential to the endeavor. Here is the target area chosen:

The landing attempt began

in the afternoon (EST) of February 12. Five burns (fuel blasts) were involved

over a 50 minute interval, each slowing the spacecraft and thus causing it to

drop ever closer to the surface. The last burn dropped the descent speed to 6

km/hr (4 mph). All the while, images were taken and radioed to Earth. The spacecraft

not only reached the surface but survived the touchdown and continued to send

back signals.

Pictures obtained as the

spacecraft moved ever closer to its landing resemble in their increasing detail

those returned from Ranger impacts on the Moon. Here is a sequence obtained

as NEAR approached a large crater (again, named Shoemaker after the dean of

astrogeologists and expert on asteroids). The caption gives the spatial resolution

achieved for each image.

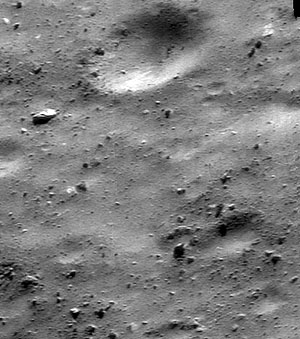

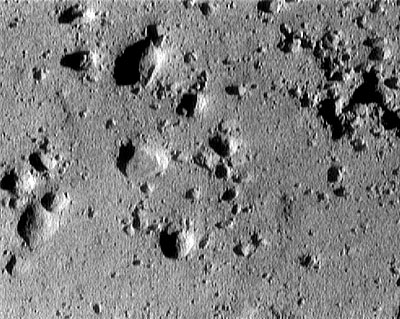

Here is a NEAR descent

image taken when the spacecraft was just 250 m (820 ft) from the surface. Rocks

less than a meter in dimension are scattered on the surface, as had been expected.

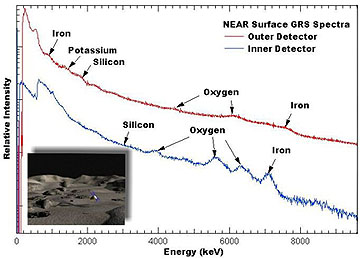

Astonishingly, the gamma

ray spectrometer on the spacecraft was not damaged. When its solar panels were

arrayed so as to pick up sunlight and hence provide power, the spectrometer

was turned on and data were collected from two depths. Here is one of the plots:

This triumph, with its

serendipitous landing results, augers well for future missions to asteroid surfaces;

sampling these (either by instrumental analysis or by sampling collecting and

return to Earth) will give scientists their first solid data on the composition

of these asteroids which have the most primitive material in the condensed planetary

rock system. This should thus confirm whether any of the meteorites fallen on

Earth were truly samples of the planetesimals which, for Earth and the inner

planets, were the primary constituents that eventually melted.

As implied on page 18-3, the dinosaur

"final solution" from a huge asteroidal impact, followed by several movies that

deal with world-threatening (and destroying) collisions with outer space debris,

have led to a more organized search and inventory (and orbit-determination)

for asteroids and comets. Optical telescope methods look for tiny light blips

in photographs that move with significant displacements relative to fixed star

backgrounds. This is turning up new asteroidal bodies - many quite small - with

notable numbers added each year. Another approach uses radar: this image of

Toutalis (4.6 x 2.4 x1.9 km [2.9 x 1.5 x 1.2 miles]) is a mosaic of several

radar returns:

19-73:

What have you seen (as images) before in Section 19 that remind

you of these asteroids? ANSWER

The question of the origin

of asteroids is still debated. All agree that they represent primitive materials

and are about as old as the planets. A few planetologists still argue that at

least some, perhaps all, of those in the Main Belt represent a disrupted planet.

But most subscribe to the concept that these are really planetesimals (accretionary

bodies built up of fragments of gravity-attracted small solids that condensed

and organized during the first stages of solar history) that never succeeded in

building up by accretion into (a) planet(s). Most of these bodies today have undergone

repeated collisions that knock off chunks from the target body, some of which

escape to become new asteroids but much (most?) re-assemble into the collided

remnant or into a neighboring asteroid to form a new shape.

Some asteroids are solid

in the conventional sense but may now consist of joined fragments (note shape

of Toutatis, which appears to have three connected pieces); these have greater

densities but may contain internal voids. Others, perhaps the majority, being

lower in density, are thought to be comprised of smaller fragments. These indeed

may even be a composite of sand, gravel, and small boulder sized material (probably

the residue of the carbonaceous silicates that were the first solar dust aggregates).

They are held together by gravity, electrostatic attraction, and possibly a

form of ice. When collisions on them occur, pieces may be knocked off but these

tend to rejoin the parent in a matter of days. Over billions of years many collsions

have occurred, reordering the asteroids into new assemblages. Most asteroidal

surfaces, whether solid or held together in a manner similar to "sand castles"

made at a beach, are covered with loose debris or "regolith".

Asteroids, and fragments

therefrom, occasionally hit the Earth, as we showed on page 18-1, dealing with

impact craters. So do comets: a possible example (although it could have been

a stony meteorite) was the 1908 Tunguska event in Siberia, where trees were

knocked down (in a radial pattern pointing to a center of blast) over many hundreds

of square kilometers by an explosion just above the surface. Great amounts of

dust were thrown into the atmosphere, producing abnormal red sunsets worldwide

for the next several years.

Comets are among the most

spectacular of the heavenly bodies with their long, icy tail, receiving mystical

significance from early observers, until later observers determined their true

nature.

19-74:

Name the comets that YOU have actually seen (through binoculars

or telescope, or even naked eye) in your lifetime. ANSWER

We now know that comets are

mainly ice balls of varying sizes (up to 10-30 km [6-19 mi]), mixed with rock

debris to some extent. They travel in eccentric orbits (e.g., Kuiper belt) within

the solar system, repeating appearances or simply flying through once, if not

captured gravitationally. As seen when still far from Earth, the central coma

appears as a glowing ball from 10,000 to 100,000 km (6,214-62,137 mi) in apparent

diameter, around a much smaller solid nucleus. A good example is the comet Encke:

As a comet passes the Sun,

the solar wind and other factors cause it to ablate, expanding the coma and creating

a stream of particles that trail off as a long tail (up to 100 million km [62,137,000

mi] long) of dust and plasma. The tail points away from the Sun along a radial

line. The coma and tail are visible because of reflected sunlight and particles

that fluoresce when irradiated by UV light. Look at the famed comet Halley.

Scientists think that the

nucleus (descriptively referred to as a "dirty snowball") consists of very primitive

materials, organized during the solar system's development. Spectroscopic studies

indicate the presence of molecular compounds of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen,

including CN, NH, NH2, and HCN, which break into ions carried into

the tail.

Astronomers know the orbits

of some comets well enough (through observations) to predict when they will return.

Most comets come from either the Kuiper Belt ( beyond Pluto or the vast Oort "Clouds"

that extend to the outer reaches of the solar system. Some may be intergalatic

but that has yet to be demonstrated.

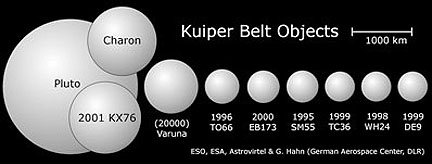

The Kuiper Belt contains Objects

(KBO) that are primarily comets but seem to also include some asteroidal type

bodies. The Belt was predicted to exist by Gerald Kuiper in the 1950s but the

first direct imaging was not achieved until the 1990s. The example shown here

indicates the difficulty in spotting such small objects far out in the Solar System;

once located, the circled object moves relative to the background, allowing its

orbital migration to be calculated.

The KBOs are clustered

in a disk-shaped region near the ecliptic (plane in which most of the planets

orbit the Sun), lie at distances from 30 to 100 A.U., and may contain up to

(an estimated) 100,000 objects larger than 20 km in diameter. Centaur-class

KBOs are relatively close to Neptune's orbit and include the icy body named

Chiron (discovered in 1977; at first thought to be an asteroid but now proved

to be a comet with a short tail); of the estimated 400 Centaur objects greater

than 100 km in diameter, at least 9 are notably larger.

The biggest known KBO asteroid

is 2002 LM60, discovered first by a ground telescope (making it the farthest solar

system object yet found) and then confirmed and studied by the Hubble Space Telescope.

The discoverers have named this Quaoar (pronounced Kwa o whar), an American Indian

name associated with the tribe that once occupied the Los Angeles Basin. The asteroid

is spherical (indicating that it was once molten) and is close to 1250 km (780

miles in diameter). Quaoar is 6.5 billion kilometers from the Sun, around which

it moves in a circular orbit. It lies 1.5 billion kilometers (about one billion

miles) past Pluto. Another recently discovered asteroid is 2001 KX76, named Ixion,

whose size ~1200 km (745 miles). The largest objects in this belt (using Pluto

and its moon Charon for comparison, are depicted in this schematic:

The Oort Cloud (OC) is

a postulated swarm of perhaps billions of comets that orbit farther from the

Sun than the KBOs. These orbits are not confined close to the ecliptic but can

follow paths that occur anywhere in the "sphere" of the Solar System with the

Sun at its center. As yet, no OC object has been imaged by either ground-based

telescopes or the HST owing to their small sizes and great distances from Earth.

However, their existence is based on firm reasoning that predicts them to be

a significant part of the bodies that formed from the nebula that organized

into the Sun, planets, and other objects.

As of 1995, 878 comets have

been catalogued; most now have their orbits reasonably well calculated. Of these

184 have definitely been established as periodic (at intervals of years

to centuries pass the inner Solar System as they orbit the Sun; these can be divided

into Short-Period (KBO) and Long Period (OC) types; new comets and others of the

878 may also be periodic but more observations over time are needed to confirm

this. The number of comets - most still undetected - within the Solar System may

be in the trillions.

Most comets positioned

well away from the Sun are without pronounced tails, and are best found by looking

for notable displacements of small bright objects (early stage comas) relative

to fixed star backgrounds in film records taken days apart. Such motions delineate

the advance of comets, as well as reflecting asteroids, at high speeds through

solar space.

The best known of all comets

is Halley’s Comet, observed and recorded in ancient times. Its periodicity,

first predicted by Edmund Halley to verify Newton's Laws of Motion, causes it

to reappear about every 76 (range 75 to 79) years. Having passed in 1909, as

shown in this wide angle view that displays its magnificent tail, it reappeared

in 1986, and many predicted it would provide a great celestial display (which

generally fell short of expectations).

Debate raged in advance

about sending one or more space probes to examine it close-up, since the next

opportunity would not be until 2061. Although NASA decided against this adventure,

Japan, the former Soviet Union, and the European Space Agency sent probes to

gather data. In particular, the Italian government designed and launched a spacecraft

named Giotto, which came within 540 km (336 mi) of the nucleus on March 13,

1986. Here is a close approach view:

Giotta found that Halley's

nucleus, measured at 16 km x 8 km (10 x 5 mi), is very dark, lumpy and of low

density (0.1-0.2 g/cc). This suggests that it was then very porous, with most

of the ice having ablated or evaporated away, leaving carbon-rich dust as a

residue. Although not as bright as anticipated and a disappointment to ground

viewers, the comet, as seen through telescopes, provided exceptional displays.

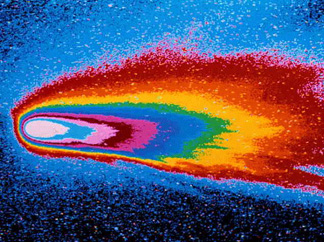

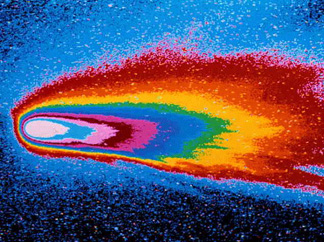

We can emphasize reflectivity variations in its coma and tail, representing

particle density differences, by displaying them in false color:

A recent comet sensation

is Comet Hale-Boggs, discovered on July 23, 1995, that passed Earth as close

as 85 million miles on April 2, 1997. Hailed by many as the Comet of the Century

because of its size (four times larger than Halley’s Comet) and brightness,

it was visible in northern and southern hemispheres during much of the first

half of 1997. Here is a typical view, taken on March 11, 1997, by Jerry Platt,

one of many amateur astronomers who tracked this spectacular celestial visitor.

Most of those that are

far from the Sun don’t have pronounced tails, so to find them we look

for notable displacements of small bright objects (early stage comas) relative

to fixed star backgrounds in film records, taken days apart. Such motions delineate

the advance of comets, as well as reflecting asteroids, at high speeds through

the solar system. The 6 panels in the next illustration show the progressive

movement over hours of the comet Wirtanen (when imaged it was about 605 million

km - or more than 4 A.U's - from Earth. The comet, a tiny dot is circled in

each panel. Follow its displacement from right to left (in panel 4 it is directly

in front of the reference background star).

In 1999, NASA sent a probe

called Deep Space 1 to test new observation techniques and if possible to gather

new information about comets it would approach. It has lasted beyond its planned

lifetime. One of its most spectacular achievements was on Sept. 22, 2001 when

it passed within 2200 km (1400 miles) of the Comet Borrelly to image its nucleus.

Concern was high that the probe, suffering now from some malfunctions, would

be damaged by cometary debris. However, it succeeded grandly in getting excellent

images of the nucleus. Below is the last image received before planned shutdown

in which the elongated nucleus, an 8 km (5 mile) long object imaged at 45 m

resolution, displays ridgelike irregularities, faults and other geologically

describable features; in some ways, it resembles an asteroid but its dark surface

is composed of ice and dust (note the jets of material streaming off):

The European Space Agency

(ESA) is planning a follow-up to Giotto with a mission (Rosetta) to the above

comet Wirtanen with launch in the year 2003 and arrival in 2012.

19-75:

How do you think comets have influenced the Earth in history?

ANSWER