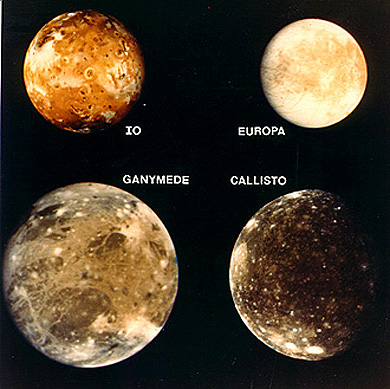

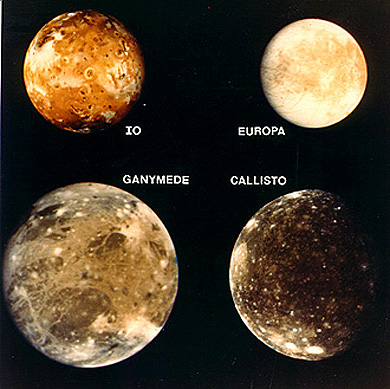

Jupiter has 16 satellites or moons (we use the term "moon" to describe spherical satellites while "satellite" may apply to an irregularly-shaped body). All but four are small and irregular, and most of those were discovered by telescope from Earth, but Voyager found three. We generally consider the four large ones, known as the Galilean Moons, in honor of the Italian scientist, Galileo, as the most extraordinary, as a group, in the solar system. We introduce these now in the Voyager montage below, created from individual global (full) views scaled, so that each retains its size, relative to the others:

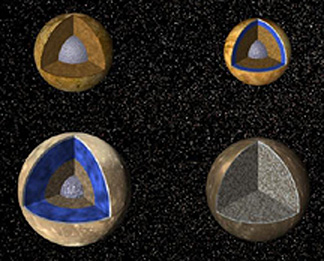

Data gathered both by the Voyager and Galileo spacecraft on the densities and nature of the crusts of these four Moons have resulted in general models of the interior of each. Io (upper left), Europa (upper right), Ganymede (lower left) all have cores (denser rock; possibly some solid metal); Callisto may have a small core but its interior is thought to be mainly water ice plus rock (largely undifferentiated).

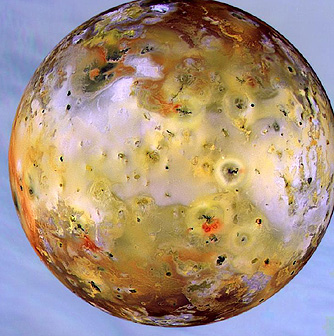

The innermost moon, Io, lies some 422,000 km (262,231 mi) from Jupiter's center. It's about 3,630 km (2256 mi) in diameter, making it just slightly larger than Earth's Moon.

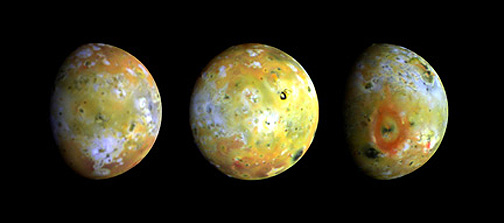

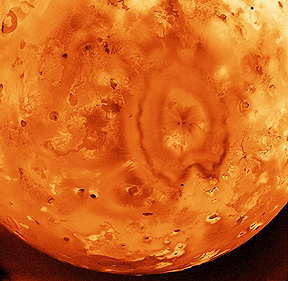

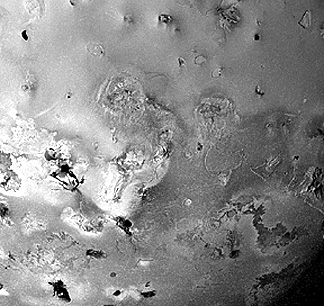

Different parts of Io are portrayed in these three views taken by the Galileo TV camera:

19-54: What common planetary feature seems to be absent on Io? Venture a guess as to what may be the dominant process acting on this satellite. ANSWER

Io displays prominent orange colors, with blackish mottled areas (that has reminded some of a giant pizza with olives). It may well be the most remarkable of all satellites, in that the surface is undergoing constant dynamic change, largely through volcanic processes. Astrogeologists have rated Io as the "most geologically active planetary body in the Solar System". What they mean is that it is undergoing more volcanic eruptions, for its size, of any such body (at least 16 volcanoes that are active have been detected); besides Earth, it is the only other object with live volcanoes spewing hot lavas. Although the ionian surface generally has a temperature of -140░ C, hot spots with temperatures up to 1200░ C attest to volcanically active areas. Io's surface is geologically young (no impact craters have been found on it), constantly undergoing "resurfacing" by volcanic processes.

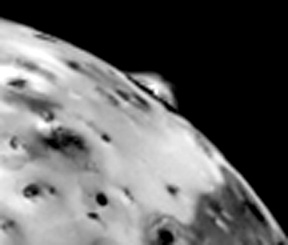

One Voyager 1 image startled JPL scientists, because it captured a major plume from the eruption of an Ionian volcano that was then tossing material up to 300 km (186 mi) above its surface. This was the first clear indication that Io was a body with (very) active volcanism.

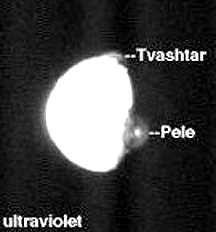

The plumes are particularly likely to be detected when their source volcanoes lie at moment on or near the limb of the illuminated/dark parts of the satellite. In this UV image made by the Cassini spacecraft, two plumes from separated volcanoes are visible against the dark background just past the limb terminator. These eruptive plumes are nearly symmetric hemispheres because of lack of strong winds to disperse the ejected materials directionally.

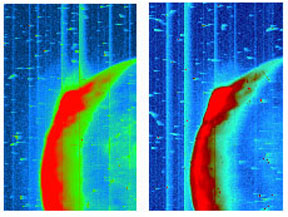

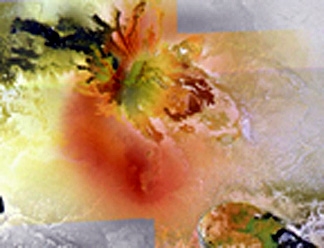

In August 2001, Galileo had a stroke of good fortune: An unknown volcanic source was caught in eruption while the spacecraft was actually looking at a different volcanic site, Tvashtar, whose activity had been persistent earlier. This time Tvashtar was apparently quiescent but a plume, imaged in the infrared, was observed along the illuminated crescent as it rose to 300 km (200 miles) above Io's surface at a point that had not earlier disclosed any discrete volcanic features. This is how this eruption appears in this observational mode; most of the excited particles causing the red color are SO2.

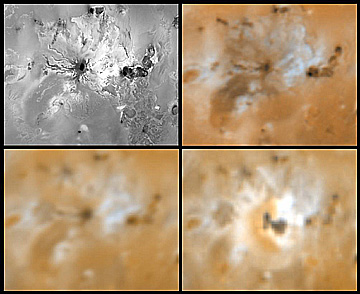

Other eruptions were "caught in the act" during the fly-bys meaning that, along with signs of young surface deposits, for its size Io is more volcanically active than Earth. A major eruption in progress at a volcano named Prometheus was captured by the Galileo TV camera, as depicted in these two views:

19-55: Look at the Prometheus images. How does this eruption differ from the usual big ones (typically from stratovolcanoes) on Earth? ANSWER

By comparing images of Prometheus acquired by Voyager in 1979 (left) and Galileo in 1997 (right), several distinguishable major changes are evident:

The caldera central to the Pele eruption site was imaged after it had discharged sulphurous lava, ash and gases out several hundred kilometers in all directions, forming a heart-shaped halo deposit (SO2 frost), named the Matuike Patera (volcanic field).

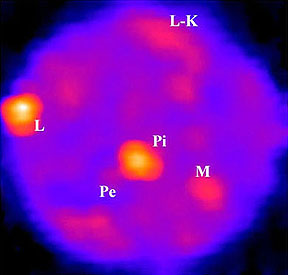

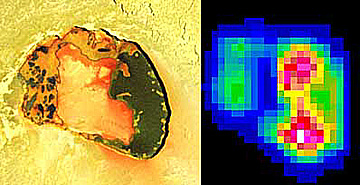

A thermal sensor on Galileo has taken measurements showing temperatures associated with specific volcanic hot spots (see caption for identities of individual volcanic centers):

The actual temperatures are

mostly low, by Earth volcano standards. The blue denotes temperatures of 90░ K

(-297░ F) and the yellow denotes 170░ K (-153░ F). But some hot spots have local

temperatures up to 1500░ K (2240░ F).

Another part of Io, overlapping

onto the Pele area, has been examined in the infrared by the European Southern

Observatory (an Earth-based telescope). The image below was made by using these

bands: 1) Blue = 1.6 Ám; 2) Green = 2.2 Ám; 3) Red = 3.8 Ám. The last band singles

out areas on Io that are notably warmer than their surroundings.

Galileo has imaged an active

or recent lava flow, still hot as suggested by its orange color. This is the

first time a "living" flow has been seen on any other planetary body:

Some of the Galileo images,

when converted to approximations of natural color but with some artistic license,

are quite attractive to behold, as is this one of Culann Patera:

At least 100 eruption sites

have been identified, but many may be inactive. More than 30 appeared to undergo

one or more events during the observation periods. Volcanic deposits dominate

the entire ionian surface, some being flows and others, probably fragmental.

We can trace many of these to calderas. This is a Galileo view of a typical

part of the ionian surface:

Volcanic sites can undergo

significant modifications in just a few years, as demonstrated by this series

of images taken over the last 18 years from Voyager 1 (upper right) through

Galileo (lower right) around the volcanic complex known as Ra Patera (upper

left):

19-56: In general terms, describe the changes at Ra Patera. ANSWER

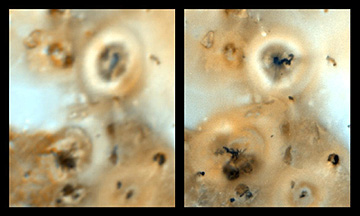

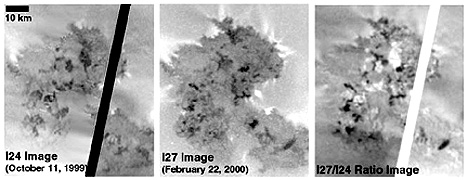

Standard image processing

for enhancement or change detection that we've used in this Tutorial for terrestrial

images work just as well for other planetary bodies. Here are three Galileo

images of an active volcanic terrain on Io. The left and center were taken four

months apart. The right image is a ratio product of the first divided by the

second date; the new tonal patterns indicate changes most probably of volcanic

deposits over this short interval.

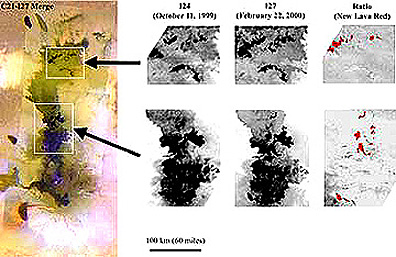

An even more recent observation

has pinpointed the volcanic complex called Amirani-Maui where new lava is pouring

out at a rate of 100 cubic meters. This is producing a lava flow continuum that

is at least 350 km long (longer than any equivalent on Earth). The images below,

on the right, show areas of new lava cover built up in just 4 1/2 months.

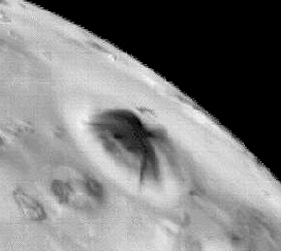

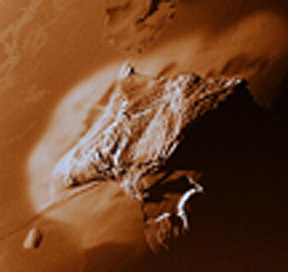

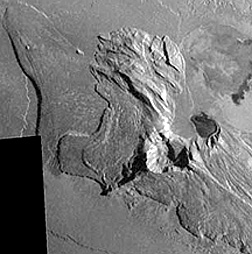

Most of the ionian volcanoes

do not appear to be high stratocones such as are displayed as the majestic volcanic

peaks observed in the Ring of Fire on Earth. Where some relief is evident, many

Ionian volcanoes are more like terrestrial shield volcanoes, often with wide

calderas. Haemus Mons is an example:

The volcanic materials are likely silicates, mixed with large amounts of (native?) sulphur and sulphur compounds. These compounds can account for Io's orange, yellow, and black colors that are typical of this element. Sulphur-rich lakes have been observed. Sulphur dioxide makes up a tenuous atmosphere.

The cause of this (totally unexpected) activity on Io is a process termed "tidal pumping," in which the outer part of this satellite flexes and stretches as much as 100 m (328 ft) as Jupiter and the other moons tug on it. The tidal energies acting on Io induce heating, and the stretching causes it to wobble.

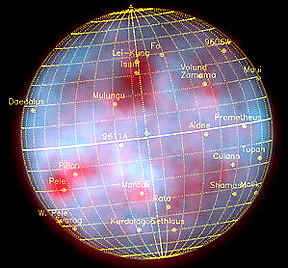

Io has the highest degree

of volcanic activity of any planetary body in the solar system. Some of this

activity was missed during the earlier imaging of Io in the visible light range.

But thermal infrared images have found at least 9 hot spots (at least some being

volcanoes) representing new locations; later inspection of visible imagery then

found evidence for most of these:

Amazingly, Io also has

the highest mountains on any of the rocky or ice-covered satellites, although

these are uncommon. Using both Voyager and Galileo images, stereo has allowed

estimates of elevations of various peaks rising from the general surface. Some

exceed 10 km (6 miles) in height (relief). One of the more prominent is Tohil

Mons, a volcano with a caldera and associated lava flows, that resembles similar

volcanoes on Earth:

Seen close up, this mountain

(~6150 m or 18500 ft high) is seen to have a subsidiary rimmed crater (to its

northeast in the above view) with a smooth central filling that appears to be

a (solidified?) lava lake.

An image made during an

October, 2001 Galileo pass by Io shows the Tupan caldera in a false color rendition

and in a thermal plot using data from the 4.7 Ám thermal channel: Recently, Galileo sent

back evidence that Io has an iron-rich core whose radius is about half (~900

km) that of the complete satellite. Io is generating a small magnetic field

that interacts with (and may be largely caused by) the intense field caused

by Jupiter. Io also seems to have an ionosphere. It is surrounded by a vapor

cloud made up of hydrogen, sodium, potassium, and ionized sulfur (derived by

sputtering off the ionian surface) which has been stretched out to form a torus

around its parent planet. A flux tube between Io and Jupiter allows a current

of 10 million amps. to flow. As would be expected on

such an active, dynamic planet-like surface, other processes besides volcanism

are taking place. This Galileo image shows landslides against the steep front

of the Telegonus Plateau:

Io also has an atmosphere

made up of gases and dust ejected from the volcanoes (most eventually escaping

to space) and ionized particles. This next Galileo image shows the atmosphere

(reddish band near top) and volcanoes in eruption.

Galileo has made a remarkable

image of the presence of ionized sodium in its ionosphere. Sodium ions when excited

give off visible light (remember sodium vapor lamps) at 5890 angstroms (or 589

nanometers or 0.589 Ám). Using a yellow-green filter, its camera captured this

view of Io and surrounding space. The yellow is an approximation of the sodium

light. In the Io sphere, the Sun has lit the far side, as seen here, but there

is a bright white light on the dark side which is sunlight illuminating the plume

of ash coming from a Prometheus eruption in progress.

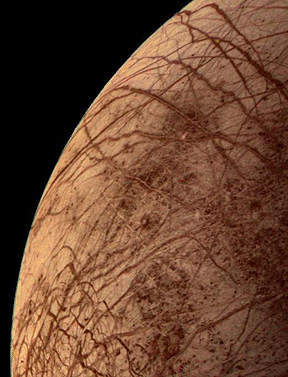

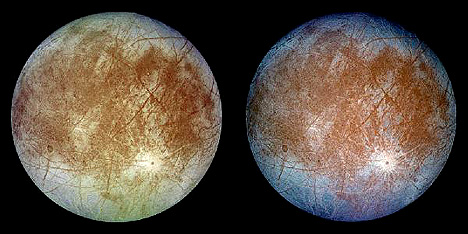

Our next moon is Europa

(diameter = 3,140 km (1951 mi), 671,000 km (416959 mi) from Jupiter. Below are

images (using different filter combinations), as it appears from Galileo:

The present ionian surface

is now believed to be quite young since lava flows like those shown above are

commonplace. With such activity, the surface is continually being replated with

lava cover. Some planetary geologists contend that Io's surface today is similar

to that of the early Earth, in its first billion years, and is thus a "living"

model of terrestrial conditions not long after its formative years (involving

intense planetesimal bombardment and cratering) came to a close and a continuous

crust developed. However, the Earth of about 800,000 years of age probably didn't

have a sulphur-rich crust.

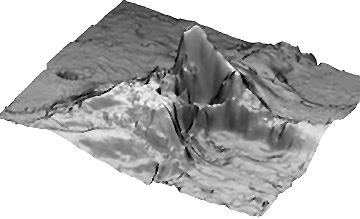

This next image is a perspective

recreation (with added vertical exaggeration) from the above imagery of Tohil

Mons; note that the viewing direction is different. The peak is more than 6 km

(20000 ft) above the plains.

This next image is a perspective

recreation (with added vertical exaggeration) from the above imagery of Tohil

Mons; note that the viewing direction is different. The peak is more than 6 km

(20000 ft) above the plains.

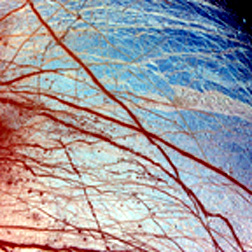

Europa's surface reminds some viewers of a giant "cue ball" that has cracked with age. The left view is a natural color image. On the right is a false color image, made by projecting the violet band through blue, the green band through green, and the IR through red.

19-57: What Earthly object with which you may be familiar does Europa remind you of (hint: think of a game you play indoors)? ANSWER

Seen by Voyager close up, the surface is extremely smooth, with few markings (minimal craters). Much of the ice making up the europan surface is blue, similar to fresh ice found in polar regions or in glaciers on Earth. This is typical:

Other regions on Europa have

a brown coloration. These contain pronounced sets of darker brown "fractures"

that divide the crust into polygonal segments. These cracks are only slightly

higher or lower (<300 m [984 ft]) than the main surface that appears to be

water ice, which may top an ice-water slush or a pure water "ocean" at some depth

before grading again into ice and then rocky material.

Another view in the Minos

Linea region of this surface from Galileo has been reprocessed to give a color

version in which the ice is blue and the crack-filling material is dark red

- a color very close to that of hematite, the non-hydrated form of iron oxide

(suggestive, but not proof it is that mineral).

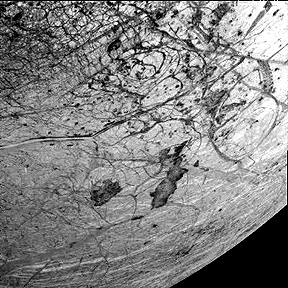

At higher resolution, we

can see several orders (size discontinuities) of fracturing. Some are distinctly

curvilinear (a common pattern in rapidly cooled liquids, such as those used

to make silicate glass). Slivers of dark material are scattered within. On Europa,

some interior rocky material may mix with the ice. The origin of these linear

breaks is uncertain. Scientists compare these breaks with polar sea ice on Earth,

which experience cracks or "leads" by tension, as water currents cause them

to flex. These cracks then reheal. Ridges, formed by compression, are an alternative.

The cracks may be curvilinear

as well, as seen in this view of the Theros and Thrace region near the southern

pole of Europa.

19-58: On what basis can you conclude that Europa's surface is relatively

young? ANSWER

Galileo shed more light

on this, when it made a close approach (586 km [364 miles]),on February 20,

1997. The picture below shows closely-spaced parallel cracks, with different

orientations, in two blocks separated by a high ridge, furrowed in its center.

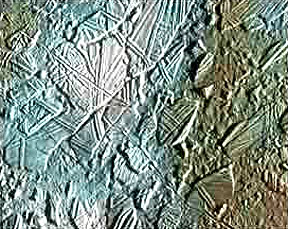

This image shows in addition

to cracks, a break-up of the crust that produces what have been called "ice

rafts" which rise above the surface. Individual rafts are grooved, but the grooves

vary from raft to raft indicating that they floated as breakoffs from grooved

terrain or alternatively were reoriented by pushing around from a disrupted

terrain.

These appear to be break-ups

of a thin ice cover (with its leads), in which the rafts are free to move about,

with additional evidence favoring a liquid water body below. The implication

of a liquid "ocean" topped by a frozen crust (analogous to the polar arctic

on Earth) has led some scientists to speculate that conditions may be favorable

for primitive life in this liquid. This supposition has fueled intense interest

in getting even closer approaches to Europa, which planners scheduled in the

continuing Galileo observations. Officials are considering a new mission in

the early 21st century, specifically to search for more signs of life. More recent observations

shed further light on the variety of terrains on Europa. The scene below,

covering an area of 7 km by 4 km (4.3 mi x 2.5 mi), shows a chaos of small

plates and wedges in an area known as Conamara Chaos. This December 16, 1997,

image reveals chunks of ice, perhaps bound to each other by a matrix of ice

mush, including several hillocks rising to 250 m (820 ft). Note the single

flat lineated plate at the top. On the left is a straight chasm that is nearly

400 m (1312 ft) across.

Recently, Europa investigators

have proposed the possibility of "ice volcanoes" in which viscous ice (perhaps

with some water) erupts from vents and flows like a glacier over the surface.

Galileo has imaged such flows, as seen in this image in which a flow (in the

center) is extending over large cracks.

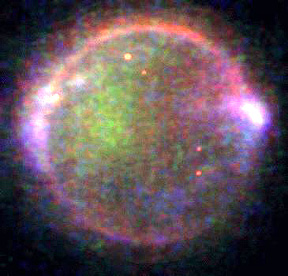

Although impact craters,

especially larger ones, are quite uncommon on Europa, a few exist, such as this

one, not yet destroyed by ice movements, known as Tyre Crater. This sparsity

indicates that Europa is an active planet, with continual or periodic replating

of its surface in a process affected by the presumed liquid ocean beneath its

ice cover.