In view of the tremendous

energies involved, it is no wonder then that we classify the Chicxulub impact

in the Yucatan Peninsula as one of the biggest short-term natural events known

in the geologic record (of nuclear-equivalent magnitude in excess of 100 million

megatons). It occurred 65 million years ago and led to a 200-300 km (>150

mi) wide (there’s still some uncertainty regarding the location of the

outer rim) and perhaps 16 km (10 mi) deep depression. This huge structure has

no evident surface expression, being covered by younger sedimenary rocks, but

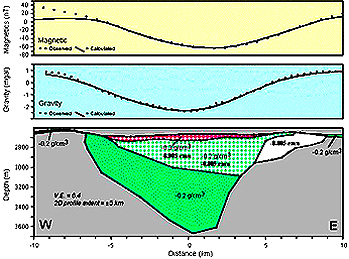

does appear subsurface as a strong gravity anomaly, as shown below. It was discovered

almost incidentally through oil drilling, in which core samples, containing

so-called volcanic rocks (now known as shock-melted rock), showed distinct shock

effects. The samples languished for years in the basement of the University

of New Orleans' Geology Building, before someone re-examined them and discovered

their origin.

The Chicxulub impact into shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico generated huge waves and, even more destructive to the planet, tossed enormous amounts of rock and water into the atmosphere. These materials, in turn, caused a worldwide "cloud deck" of aerosols, gases and particulates leading to temperature fluctuations and reduced photosynthesis that wiped out much of the food chain and provided the "coup de grace" to the few dinosaur families still living then on Earth. The resulting debris that ejected into high altitudes spread around the globe and settled as a thin layer of material that marks the precise K/T boundary between the last rocks of the Cretaceous (symbol K) Period and the first sediments formed in the younger (overlying) Tertiary Period (symbol T). The deposits contain iridium, a metallic element present in some meteorites, and mineral grains that bear evidence of intense shock (see below).

The deposits at the K-T boundary are usually very thin. They represent the fallout layer that may have been worldwide in distribution. Here is an example of this now-famous layer.

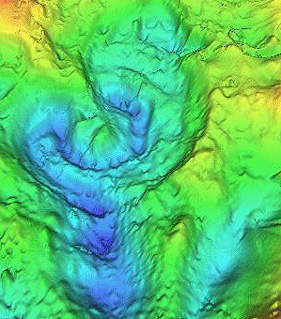

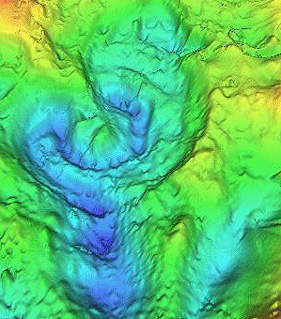

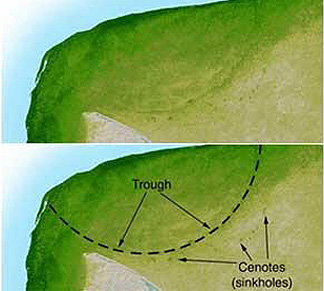

For the last 10 years or so it was thought that Chicxulub could not be recognized in space imagery because of the post-impact sedimentary rocks covering the structure and also because of dense vegetation cover. However, radar data from the SRTM program have been specially processed to bring out otherwise subtle suggestions of the buried crater rim showing its presence by some manifestation at the surface (probably induced by differential subsidence). Here is that SRTM image of much of the Yucatan Peninsula. See if you can locate the rim trace:

In case you missed this trace, here are a pair of images derived as an enlargement of the part of the Yucatan containing the Chicxulub crater. On the lower one, the rim boundary has been drawn in and the location of sink holes that seem to relate to subsurface control by the fallback material beyond the rim is marked.

Chicxulub is one of a growing number of impact structures that are buried and have been discovered during geophysical surveys. Another is the Ames structure (~13 km diameter) in northern Oklahoma, found when it was picked up by gravity and magnetic surveys and then drilled in search for oil. Here is a cross-section prepared by Prof. Judson Ahern showing the crater, its distribution of materials of different densities, and survey results:

When craters are exposed at the surface, the younger, usually less eroded ones are recognized by their morphology or external form. They are approximately circular (unless later distorted by regional deformation), have raised rims, show structural displacements in their wall rocks, and may have a central peak, consisting of rocks raised from deep original positions. We can emphasize the morphology of these craters in 3-D perspectives (commonly using Digital Elevation Map data) of their contours, exaggerating the elevations and applying shading or artificial illumination (computer-controlled). Two examples illustrate how we can make craters more obvious, when today they have moderated and often have low relief. First is the Flynn Creek structure (3.5 km [2.2 mi] wide) in Tennessee:

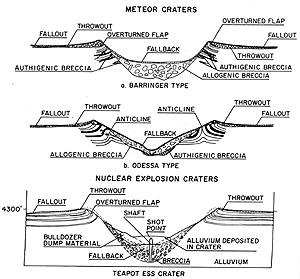

The structural deformation

in the excavated rock beyond the crater boundary is usually intense and distinctive.

Initially flat-lying layers of sedimentary rocks near the surface, beyond the

rim, are commonly deformed by upward bending (layers inclined downward [dip] away

from the crater walls). Anticlines may be formed or in the extreme the layers

are into completely overturned producing a flap in which the top layers are upside

down, flipped over on top of layers farther out. Modes of layer deformation at

two impact craters and one nuclear explosion crater are shown in this diagram.

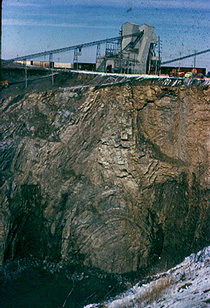

Deformation involving bending

and overturning is well exposed in the layered limestones exposed by quarrying

at the Kentland, Indiana impact structure:

One of the most famous,

and best studied, large complex craters is the the 24 km (15 mi) wide Ries Kessel

in Bavaria. (An Internet site [in German] that provides more information and

field photos is sponsored by the Ries Museum of Nordlingen).

Here is a photo montage (made by piecing together several wide-angle lens photos)

of part of this structure. (On one of its rim units, thick largely evergreen

forests develop, helping to outline the structure; the occurrence of clouds

over this unit appears to result from local evapotranspiration.)

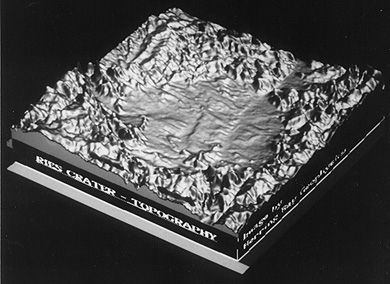

And here is a reconstruction

of its generalized subsurface structure; topography exaggerated.

18-6:

In the Ries Kessel perspective view, the crater appears surrounded

by mountains. But in reality, the actual landscape is hilly but not mountainous.

Explain the illusion. ANSWER

The Ries is young enough

for much of the ejecta that deposited in thick units (when consolidated the

general term "breccias" applies; at the Ries the special name "Suevite" is given

to this rock) to still be preserved. Here is a field exposure:

The Ries lies astride "Das

Romantische Weg" - The Romantic Way - made up of towns and cities that have

preserved much of their medieval buildings. Within the Ries is a remarkable

small town, Nordlingen, surrounded by a protective wall. Here is an aerial view

of this marvelous throw-back to another era:

Since medieval times, the

local residents in Nordlingen quarried some of the breccia deposits that had

hardened into rock. This was used as building stone. The Catholic Church near

the center of this walled city is made up of this Suevite rock; unfortunately,

the rock is easily weathered (because it contains much glass that is unstable

over time), so that the Church today is in constant need of repair. Here is

this Church:

In general, craters smaller

than 3-5 km (1.8-3.1 mi) in diameter lack central peaks, i.e, they have bowl-shaped

interiors, and we call them simple. Most larger craters have central

peaks, in which the rocks below the true crater boundary have "rebounded" upward

from the collision, further aided by centripetal forces associated with crater

wall slumping. We call these complex craters, but erosion and infill

may subdue the peaks. Flynn Creek, similar to most other craters in the U.S.

that cut into carbonate rocks, just barely received a central peak, which still

shows topographically. The Ries does not retain a morphological peak, but the

depth to the crater boundary, as determined by drilling, is less in the interior.

Simple craters (and some

larger ones) often have depressions that fill with water. On the top, below,

is the 3.5 km (2.2 mi) wide New Quebec crater in granitic shield rock, exposed

in Northern Quebec. On the bottom is the much older, West Hawk Lake structure

(2.5 km [1.6 mi] diameter) formed in metamorphic rocks in westernmost Ontario

near the line with Manitoba (rock core from which was first studied in detail

by the writer [NMS] in 1966; published in the Bulletin of the Geological Society

of America).

In Canada, and other

northern latitude countries, these lakes freeze in winter, allowing support

for drill rigs, so that we can explore the crater infill materials by recovering

core. Deposits of fragmental

rock surround most younger craters. An example (top, below) of such rock ,

from an outcrop at the Ries crater, illustrates these ejecta deposits (Suevite

breccias). A second example (bottom) seen in core from a drilling that penetrated

the Manson central peak, shows the diverse nature of the rock types making

up these breccia fragments (called clasts).

18-7:Suppose a continuous length of drill core consists of first an interval of breccia much like that shown in this figures, then a 10 meter interval of a single rock type, say granite, and followed by more small fragmental breccia. What explains this? ANSWER

Most ejecta blocks found around younger craters consists of fragmented bedrock derived from subsurface units. There can be exceptions if the surface material is unconsolidated. The writer (NMS) discovered a fabulous example of this, which at first was discounted by other specialists in this field. The crater is the small Wabar structure in the aeolian desert of southern Arabia. All around the rim are small fragments of white quartz sand, many coated with a black glass. Here is a view:

A few years earlier the writer

had "discovered" small pieces of "sandstone" around chemical explosion craters

formed in an experimental program at the Nevada Test Site (NTS), where white loose

quartz sand had been used to backfill the access hole through which the explosives

were loaded. He postulated that the fragments were made up of this sand that had

been driven together and compressed (a process he named "shock lithification",

calling the fragments "instant rock"). He proposed the same origin for the Wabar

fragments, namely, that they were desert sand shock-liithified by shock waves

from the impact (and many were then covered by shock melt that overtook them).

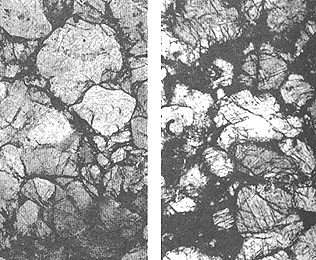

This pair of photomicrographs shows the texture of the NTS instant sandstone on

the left and the Wabar lithified fragments on the right.

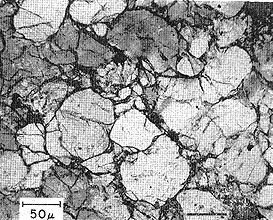

Below is a second photomicrograph

of the NTS instant sandstone, showing more details.

The paper on this interpretation

was rejected by Science Magazine because the reviewer had been there

and thought he had noted thin sandstone layers in the rim. Through a stroke

of luck, the writer, telling a colleague at Shell Oil in Houston of the discrepancy

in interpretation, was surprised to receive a call later from that friend who

reported the loose sand at Wabar was more than 200 meters thick (he had asked

a Shell field geophysical crew to run a seismic line next to the site; they

determined an accurate thickness). With this new "proof" the paper was resubmitted

to Science and was published. Eroded craters lack definitive

external shapes, although the initial circularity may have a persistent effect

on drainage, keeping streams in roughly circular courses. Such craters are often

hard to detect but the presence of anomalous structural deformation and of brecciated

rocks give clues. In rocks that were just outside the original wall boundaries,

a peculiar configuration, known as shatter cones, commonly develops.

These "striated" conical

structures (described as "horsetail"-like in shape) can be very small or can

reach six feet or more in length, as seen above in quartzites at the Sudbury,

Canada, impact structure (as an aside: the writer's "favorite" geological outcrop,

anywhere, is the low bank partly around the parking lot of the MacDonalds fast

food restaurant in downtown Sudbury, where excavators exposed a continuous cluster

of shatter cones.). When we plot the original positions of the folded rocks

containing the cones, the cone apexes invariably point toward an interior location

that lies above the central crater floor. In effect, they denote that the position

where the energy was released was above the floor, a situation incompatible

with a deep volcanic source, as once advocated by skeptics. The cones, which

also sometimes form in rocks subjected to nuclear explosions, occur in lower

(peripheral) shock pressure zones, as shock waves, spreading outward, place

the rock into tensional stress. Many cones appear to originate from point discontinuities

(e.g., a pebble) as though the waves were diffracted. 18-8:

Try to explain what happens to cause the apex of a shatter cone

to point towards the upper center of the crater near the point of impact.

ANSWER