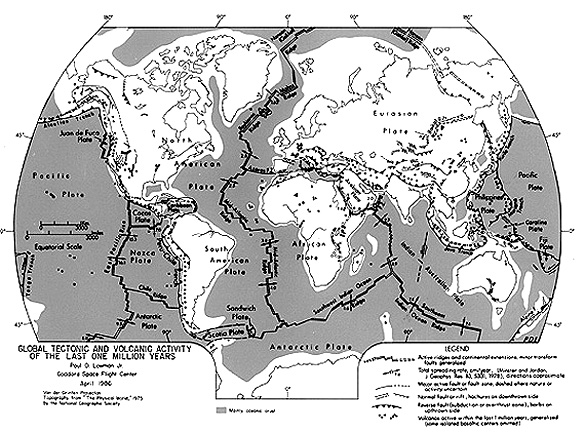

Tectonic landforms usually

dominate the scenery in any region that has experienced significant crustal

disturbances, and this activity often shows as truly spectacular expressions

in remote sensing images. For this reason, the theme chapter by this title in

"Geomorphology from Space" is by far the longest. These landforms frequently

reveal surface manifestations of the type of underlying deformation caused by

plate tectonic interactions. Some of these interactions characterize orogenic

(mountain) belts at subduction zones (convergence of two or more plates) or

pull-apart regions where plates diverge. For anyone unfamiliar with the first-order

framework of the global tectonic system, examine this map produced by Paul D.

Lowman, Jr. (author of Section 12) of the lithospheric plates, spreading ridges,

transform faults, and other tectonic features. Consult any introductory Geology

textbook for more information on the Plate Tectonic paradigm.

We described some exceptional

examples (drawing upon mostly Landsat images) of tectonic landforms in Sections

2, 6, and 7, which you can review (look particularly at the Zagros

folds, the Pindus thrust belts, the Atlas

Mountains, and the Altyn

Tagh fault in Section 2 and the Appalachian folds and Basin

and Range block fault mountains in Section 6, and the European

Alps in Section 7.

These images focused on

folds and faults, the most common types of tectonic deformation. The resulting

landforms commonly have elevation differences (relief) that may be sufficient

to change ecosystems developed at these heights. Thus, mountains in a semi-arid

climate may be heavily vegetated (dark toned in visible band images) and adjacent

basins less so (light), thus, showing strong contrasts in black and white images

(the Nimbus 3 image of the Wyoming mountains in Section 14 is a good

example). Mountainous terrains appear clearly in Landsat, HCMM, and radar images

by virtue of shadowing, which causes tonal variations related to slope/sun positions.

HCMM is especially suited

to showing large segments of a mountain belt. Perhaps the most famous in the

world, in terms of how its origin has been interpreted to lead to some earlier

hypotheses on formation of orogenic belts, is the Appalachians. Examine the

HCMM mid-Appalachians image found on page 6-3 The Rocky Mountains in

the U.S. were examined on page

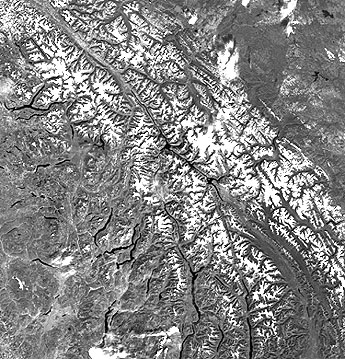

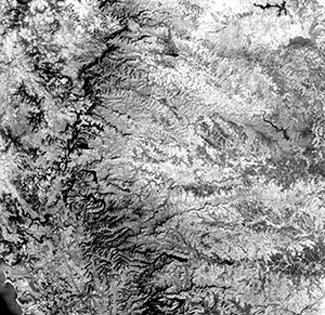

6-6. They continue into Canada and in Alberta and British Columbia almost

merge with the Coast Range and other Cordilleran mountain chains. Here is a

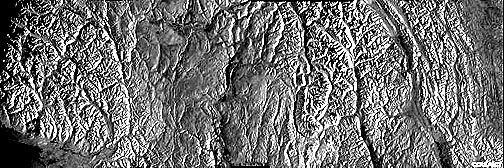

Landsat mosaic that shows some of the Canadian Rockies. Below it is a strip

across those Rockies made from Radarsat imagery.

And here is a aerial oblique

view of typical mountain terrain in part of the Canadian Rockies; the broad

valley has been widened by glaciation and backfilled with post-glacial deposits:

Recall the Landsat mosaic

that showed much of the vast chains of interrelated mountain belts in southern

Asia where the "crash" of the Indian subcontinent over the last 40 million years

created the Himalayas on the north and folds in Pakistan and Iran in the west

and others in Burma (Myomar) (see page 5-5) and Malaysia in the

east. A spectacular oblique view of the main Himalayas, taken by an astronaut

using a film camera, was shown on page 12-4. Here is another

astronaut photo, made with the Large Format Camera, covering much of the same

scene, including the Siwalik Hills (dark, near bottom), the snow-covered main

high Himalayas, and the southern Tibetan Plateau (on average, the highest generally

flat landmass in the world).

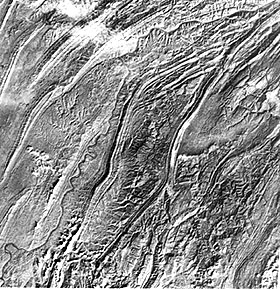

To see more detail in the

flanking mountains in western Pakistan, here is part of the fold belt that came

from the huge collision between the Indian subcontinent and southern Asia (the

context of this is evident in the mosaic examined earlier in Section 7). The scene shows the Sulaiman

fold belt, consisting of echelon (offset) anticlines (some closed), making up

the ridges (flat valleys occupy intervening synclines). The Kingri fault passes

through the image center (look for an abrupt discontinuity). The crustal block

to its west (left) has moved northward relative to the block on the east.

17-3:

As a generalization, would you say that the "style" of deformation

in the Anti-Atlas and Pakistan scenes is similar or dissimilar? ANSWER

The tectonics of southern

Asia is dominated by the Himalayan docking event. Subsidiary tectonic disturbances

occur beyond the Himalayas. In central China is this scene (with the through-flowing

Yangtze River) of what are known as decollement folds formed within thrust

sheets (like wrinkles on a sliding rug).

To the west of the Indian

subcontinental plate is the Arabian tectonic plate, caught between the African,

Eurasian, and Indian-Australian plates as they move in different directions. The

western part of this plate is a crystalline shield (a continental nucleus containing

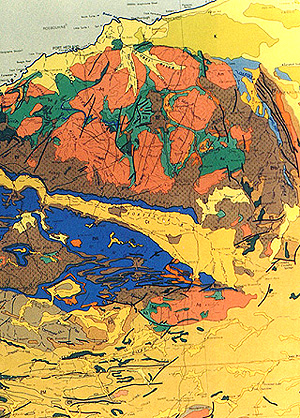

ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks). Below is a mosaic (from 12 individual

Landsat scenes) of the shield as exposed in southern Saudi Arabia and the Yemen

Arab Republic.

Dominant features in this

scene are the numerous granitic intrusions, whose boundaries show as distorted

oval shapes. The shield is a region of low mountains separated by valleys, many

of which are sand-covered. A prominent escarpment (near the upper, left edge)

bounds the western edge of the shield. The coastal plain is edged by a fault-controlled

scarp. Another scarp (lower right) also relates to the fault. 17-4:

Broadly speaking, how does the tectonic "style" of this Arabian

Shield scene differ from that of the previous two images? ANSWER

On the east side of the

Arabian Peninsula, in Oman, are the Oman mountains, large parts of which are

composed of ophiolites. These are ultramafic igneous rocks (peridoties; some

gabbros), first extruded as lavas with shallow intrusives below, that moved

as ocean floor away from a spreading ridge. On contacting a continental mass

at a subduction zone, the ophiolites may subduct but otherwise can also be thrust

on (obducted) to the continental edge. In this Landsat image the ophiolites

are the dark bluish-black masses.

Another remarkable mosaic

covers much of northwestern Australia, a region of limited vegetation so that

the rocks and valley-fill stand out and reveal much of their underlying structure.

This is the Western Australian shield, containing mostly Precambrian metasedimentary

and metavolcanic rocks, interlaced in places by igneous rocks. At the top of the

mosaic is the Pilbara block, a leading candidate for the classic expression of

an ancient greenstone-granite complex anywhere on Earth.

The granite appears as

batholiths, up to a 100 km (62 mi) long. These light rocks are diapiric intrusions

into the dark greenstones (metamorphosed basalt). To the south is the Hamersley

Range (blue area on the map) and the smaller Opthalmia Range (red), bordered

on the south by the Ashburton Trough (left) and the Bangemall basin (right).

Low-relief hills mark much of the region. The highest area (1,235 m, 4,051

ft) is in the Hamersley Range. 17-5:

The upper and lower half of the Australian mosaic are tectonically

different. What might this difference be (tectonically)? ANSWER

Turning now to volcanic

landforms, we show three images that represent two major types of volcanoes.Then,

we look at terrains carved into vast sheets of volcanic flows or flood basalts.

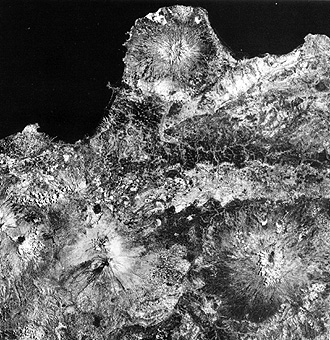

Above is the Big Island of

Hawaii (see pages 9-7

and 14-11 for other renditions).

Mauna Loa is the central part of a huge shield volcano, which comprises the entire

island. Its summit crater, a collapsed caldera named Mokuaweoweo, lies beneath

a crest at 4,135 m (13,563 ft). Its base lies about 4,000 m (13,120 ft) below

sea level, which makes it the tallest single mountain in the world (Everest, while

higher, rises from the valleys of the Himalayas that are thousands of meters above

sea level, so its relief is less). Mauna Kea, a crater on the north section of

the island, is now extinct. But the most active volcano in the world, Kilauea,

lies along the east side of the island and is visible here as a dark patch. This

island is quite young, consisting of multiple layers of basaltic flows built up

in the last one million years. Numerous lava flows (dark basalt), many extruded

over the last few centuries, emanate from Mauna Loa, as seen in this photo taken

by astronauts aboard the International Space Station:

Hawaii is the latest in

a series of volcanic islands formed from melted lower crustal rocks as the Pacific

plate moves northwestward over a fixed hot spot in the Earth's mantle. A newer

submarine, volcanic complex, now forming southeast of Hawaii, will eventually

surface and replace the Big Island as the center of activity. The Islands to

the northwest, including Oahu and Maui, were formed earlier as the Pacific plate

passed over them in succession. These others are shown here in a Terra MISR

image:

The other spectacular type

of volcano is the stratocone, noted for its steep sides and, often, its symmetrical

form. In the U.S. Mainland, the most photogenic stratovolcanoes are in the Cascade

Mountains (from Northern California into Northern Washington), and in the Aleutian

Islands of Alaska. The photo below shows the north side of Mount Rainier, a

massive, still active volcano rising to 4300 m (14411 ft) to the southeast of

Seattle, WA. Like most other Cascade stratocones, this volcano is superimposed

on older, much eroded volcanic rocks from earlier periods of volcanism. Below

the photo is a view from space made from multiband radar imagery acquired by

SIR-C.

Below is a Landsat view of

a segment of Java, the main island in the Indonesian archipelago, a prime example

of an island arc terrane still evolving.

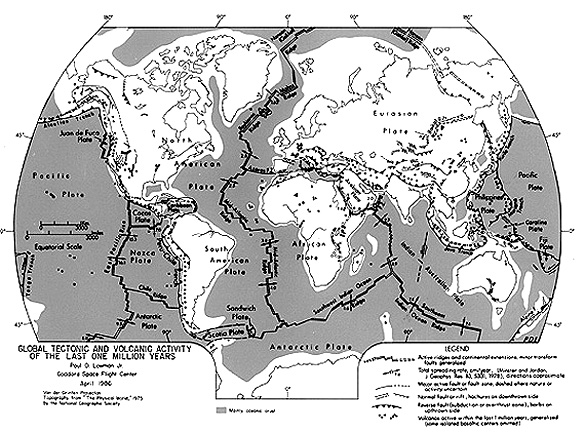

In the midst of thick sequences

of geosynclinal sediments are a series of large composite stratovolcanoes, developed

from crustal melt induced by frictional heat, as the Indian-Australian plate

dives in subduction below the southernmost extension of the Eurasian plate (see

the tectonic map at the top of this page). The stratocone on the north peninsula

near the Java Sea is Muria. The highest (2,910 m, 9,545 ft) volcano is the active

Merapi, which stands out as the lower of two in the left center. To its right

is Lawu. Six other large volcanoes are mainly to the west (left) of Merapi.

17-6:

What is missing volcanically in the Java image that is present in

the Hawaiian scene? ANSWER

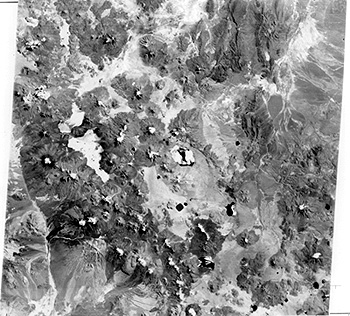

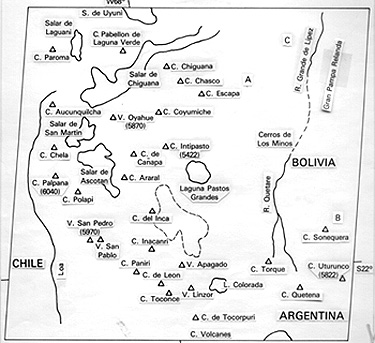

Stratocones come in various

sizes and can occur in swarms. This is particularly a hallmark of volcanoes

in the South American Andes Mountains as seen below. Use the sketch map as an

aid to picking out the individual cones, many of which are snow-capped in this

southern fall image, owing to the high elevations of the flanks of the High

Andes.

Lavas (magmas that reach the

surface) extrude not only from discrete individual volcanoes but from deep-reaching

fractures in the crust that can tap into the upper mantle. The result is widespread

flows covering large areas. We saw one example in Section 3 of basaltic flows

in the East African Rift. This huge fracture zone runs across much of the eastern

side of that continent as one of the "arms" of splitting tectonic plates. Two

other arms or dividing zones, where Africa is breaking off from the Arabian plate

and from the Australo-Indian plate, meet the newly developing East African arm

at a "triple junction" located in the Afar of Ethiopia. This junction was captured

photographically by astronauts on the Earth-orbiting Apollo 7 (pre-lunar) mission:

Associated with the rifts,

beyond the apex of these spreading centers, great quantities of basaltic lavas

are pouring over the surface in the Afar Triangle. This locale was photographed

with the Large Format Camera, from the Shuttle, as seen here:

Well south along the East

African Rift, the fault zone in the basalts narrows. Here is that segment, part

in Kenya and the southern part in Tanzania. In the upper right is the great

stratocone of Mt Kenya; its larger companion, Mt. Kilimanjaro is in the lower

right:

Flood basalts, extruding

from many fissures, and moving out to cover 100s of thousands of square kilometers,

are found on several continents. They occur mainly in active tectonic zones.

The Columbia River and Snake River basalts of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho

form one such plateau of lavas piled on lavas, the many successive outflows

producing distinct layering. In western India is the Deccan plateau basalts,

whose extrusions for more than 70 million years are related to the collision

of India against the southern margin of the Asian plate. A Landsat view shows

the landscape, often barren, mountainous, and with a lower population density.

The photo below it reveals the nature of the flow layers.

It is worth commenting

that much/most of the exteriors of the other inner or terrestrial planets, and

our Moon, are surfaced by countless basalt flows. (And, of course, this applies

to the bedrock below marine sediments on the Earth's ocean floors.)