The very idea of the presence of the material on these next three pages comes as a surprise to the writer in that the idea for the inclusion of applications of remote sensing to the medical profession's need to examine humans and animals by sophisticated imaging instruments never once occurred to him in the first five years in which the Tutorial was being developed. (No one else ever called this omission to his attention.) But, then, in May of 2002 he was given an echocardiogram (which uses ultrasonic waves to image the body's interior) and a light in his brain flashed on: Many of the techniques of using high-powered instruments to send electromagnetic and sonic waves into the human target (we shall assume that "animal" is understood implicitly to be included since at least some of these instruments have been used to examine dogs, cats, horses, etc.) fall within the broader definition of remote sensing - electromagnetic radiation photons (at different wavelengths) or sonic wave trains are generated and coupled to the body and then detected as transmitted, absorbed, or reflected signals to an external detector a short distance away. Most medical remote sensing is of the active mode, i.e., EM radiation or acoustical waves generated by the instrument are sent into or through the body. Some examinations of bodily functions depend on implanting (by injection or swallowing) a source of radiation, such as radioactive element(s) as tracers which can be sensed by appropriate detectors as they move about (as in the blood) or concentrate within organs - this approach is analogous to passive remote sensing.

The subject of medical remote

sensing (more commonly referred to as medical imaging) is now a major topic covered

on the Internet. One quick overview is found at this site put together at the

Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory.

Another of general interest is at this site. A third broad review

site is the oft-consulted How Stuff Works

site. Once there, click first on "Body and Health" and when that comes up

choose "Health Care" and look for the box category of interest (one of the imaging

methods); or, type in the specific method in the Search box. Finally, consult

a very informative survey of principal imaging methods, including the physics

involved, prepared by

Dr. D. Rampolo.

In the Tutorial, we will

cover these methods: X-ray Radiography; X-ray Fluoroscopy; Computer Assisted

Tomography (CAT scans); Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI); SPECT (Single Photo

Emission-Computed Tomography; Positron Emission Tomography (PET); CATscan-SPECT

combined; Infrared Imaging Thermography; Ultrasound; and Endoscopy. PET and

SPECT also fall in the realm of nuclear medicine. These various methods can

produce "static" images or can be viewed in real time to examine "movements"

within the body. Also, some methods concentrate on skeletal parts (bone), others

on internal organs (e.g., brain; heart; kidneys); others on circulation and

other functions. Most methods are used to detect abnormalities such as malignant

growths, bone breaks, and disease effects. Modern medical imaging

began with an almost accidental discovery in the lab of Professor Wilhelm Roentgen

in Germany on a November day in 1895.

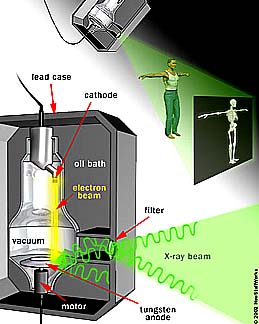

Roentgen was experimenting

with a Crooke's Tube he had recently obtained from its inventor. This is a glass

vessel from which air is withdrawn creating a near vacuum; at one end is an

anode (positively charged) and at the other a cathode (negatively charged source

of electrons); the tube is wired to be part of an electrical circuit. When a

current is passed between these electrodes, the few particles within the tube

are excited and fluoresce or glow (commonly blue or green); this results from

the flow of high speed electrons (cathode rays) across the (voltage) potential

difference imposed in the circuit. Roentgen had placed the Tube in a black box

but to his amazement noted that a fluorescent screen nearby was glowing of its

phosphors which he deduced to be excitement by radiation escaping the box. This

unknown (X) radiation he simply labelled X-rays (they are also called Roentgen

rays). As he studied their properties, he experimented by putting a hand on

a fluorescent screen directly in the path of this radiation, getting this famous

picture:

Soon others were experimenting

with x-rays. The first medical uses of x-ray machines occurred within a year.

Roentgen's achievement was recognized in 1901 when he received the first Nobel

Prize in Physics. A fascinating account of his discovery is given at this Internet

site. X-rays are produced when

electrons are impelled against an anode metal target (tungsten; copper; molybdenum;

platinum; others) as they pass through a vacuum tube at high speeds driven by

voltages from 10 to 1000 kilovolts (kV). When incoming electrons interact with

inner electrons in the metal, these latter are driven momentarily to higher

energy levels (these orbital electrons are pushed into outer orbitals); when

these excited electrons drop back to their initial orbits (a transition from

a higher to a lower energy level), the energy they acquired is given off as

radiation, including x-rays . Some of the scattered x-rays are collimated into

beams (typically at conical angles up to 35°) that are directed towards targets

(such as the human body). Soft body tissue absorbs less x-rays, i.e., passes

more of the radiation, whereas bone and other solids prevent most of the x-rays

from transmitting through the body mass. (X-rays have other uses, such as examining

metals for flaws or determining crystal structure.) Here is a diagram of a typical

x-ray machine setup:

Two classes of detectors

record the x-ray-generated image: 1)Photographic film, in which the difference

in gray levels or tones relates to varying absorption of the radiation in the

beam impinging on the target (the convention is to use the exposed film [x-rays

act on the silver halide {see page 12 of this Introduction} to reduce it to

metal silver grains] in its negative form, such that bone will appear nearly

white [thus, because bone absorbs efficiently, few x-rays strike the corresponding

part of the film, leaving it largely unexposed; the soft tissue equivalents

pass much more radiation and darken the film]); 2) fluorescent screens, that

include phospors (elements or compounds that fluoresce or phosphoresce) coating

a substrate; this occurs when electrons in the phosphors jump to higher level

orbitals, with visible light given off either instantly when the electrons transition

back to the lower state or with a time delay fractions of a second or seconds

(afterglow), in a process similar to x-ray production; typical phosphors include

Calcium tungstate or Barium Lead sulphate (many other compounds are available

such as Lead oxide or those containing Gadolinium or Lanthanum; these screens

in certain configurations allow realtime movements of the medical patient to

be observed and the sreen images can be photographed or digitized. Here is a typical hospital

examining room that contains the setup used in x-ray radiology; the table on

which the patient lies that can, in some instruments, be raised to a vertical

position.

X-ray radiology is still

the most commonly used medical instrument technique. Here are a sequence of

images that illustrate typical uses and results. The first is a chest x-ray,

(the skeletal bones are whitish since they absorb the radiation and thus the

negative is not darkened and the lungs dark because more of the radiation has

passed through them):

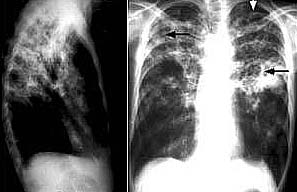

This next is a front and

side view of the upper torso; the arrow points to a tuberculosis patch in the

left lung:

Here is a negative x-ray

film image of the pelvic area:

Compare this recent image

of the human hand with that shown above as the first ever taken:

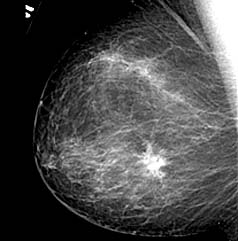

This next picture is a

mammogram showing a growth in the female breast:

The human skull is x-rayed

mainly to spot signs of fracture. But, sometimes indications of tumors are present,

as shown by the darker gray patch in the cranium of this individual's skull:

The jaw and teeth are evident

in this lateral view of the lower human skull:

Most of us gain our first

experience and insight into x-rays when we have a small film inserted into our

mouth and then the x-ray machine is placed against that part of our jaw. Here

is a typical x-ray image of teeth, in which the whitest part of the negative

corresponds to metal fillings:

An important variation

in x-ray radiography is Fluoroscopy. In this method, either chemicals

that react with x-rays are swallowed or inserted as an enema or chemicals/dyes

are injected into the blood stream. These tend to increase the contrast between

soft tissue response in the parts of the body receiving these fluids and surrounding

bone and tissue. This pictorially highlights abnormalities. Barium sulphate is a good

example. When swallowed (either at once or commonly in gulps), the "Barium Cocktail"

is especially useful in examining the digestive track. In this image, an obstruction

in the esophagus carrying food and liquids into the stomach is made evident:

The large intestine or

colon is strikingly emphasized in a patient who has just received a Barium enema:

Still another variant is

the Angiogram. This involves insertion of a catheter into an artery,

accompanied by a dye that reacts to x-rays. It is commonly used to explore the

areas in and around the heart. Here is a pair of views of the left ventricle

of the heart when it is pumping and squeezing blood and thus contracting (systolic

phase) and then expanding as blood is returned (diastolic phase):

This next image is an angiogram

that has been colored to show blood vessels including the great trunk artery

or aorta around the heart: Using special methods,

angiogram-like images can be made for the blood vessels in the human head:

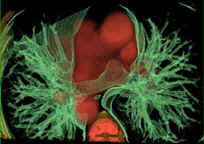

We move on now to a powerful

new approach to medical imaging, based on the technique of tomography,

which uses computers to assist in obtaining three-dimensional images or image

slices when either x-rays or radioactive elements (nuclear medicine) are involved

in producing radiation-based imagery.