Introduction

He sells his produce to the nearby HAL (Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd) market.

"If I take it to the market, people who know about our crops do not purchase it," Hanumanthappa says. "They know that we use polluted lake water."

A vendor at the market, Shashikala, says she and her colleagues avoid produce from this part of Bangalore. "If [the water] comes directly from the lake, then there will be contamination," she says.

Farmers here admit they lie about how they grow their produce in order to sell it. Usually, Hanumanthappa stands beside farmers from a different village and demands the same price as they do. He doesn't reveal to customers where his own produce comes from.

"People may lose trust… [but] I have no other choice but to do that," Hanumanthappa says.

Media captionMuniraju Hanumanthappa says spinach is just about all he can grow

TV Ramachandra, a professor at the Indian Institute of Science and a leading authority on sustainability issues, warns that pollution in the city's lakes can get into the food supply chain through farms like Hanumanthappa's.

"It's a sustaining flow of untreated sewage and industrial fluid getting into the waterway, which is used for growing the vegetables," Prof Ramachandra says. "That's why when we did an analysis of vegetables, green leaves, cabbage, etc... We found higher amounts of heavy metals."

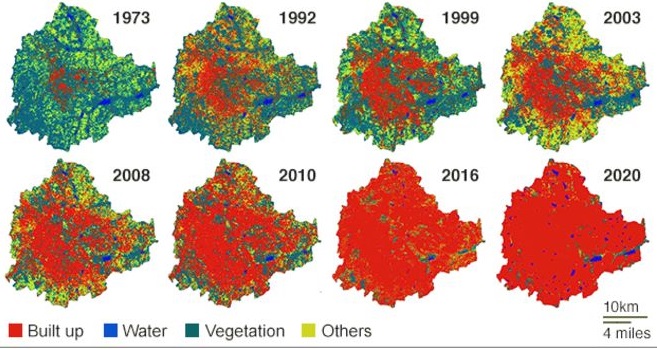

Prof Ramachandra's data also suggests that Bangalore's farmlands and green spaces are disappearing at an astonishing rate, with more high rises and commercial developments being put in their place.

Source: T.V. Ramachandra, Indian Institute of Science

According to the state government's Department of Agriculture, as Bangalore was witnessing its IT boom and burgeoning growth, the area covered by vegetable crops in the district decreased from 0.1 million hectares in 2000 to a mere 0.04 million hectares by 2015. As a result, vegetable production went down 72%, from 0.29 million tonnes to 0.08 million tonnes during the same period.

Bangalore's vanishing green space

The city's development doesn't just affect farmers. It is being driven by vast numbers of people coming to the city, many to work in the vibrant IT sector. They all need access to reliable food sources. But some people in Bangalore's affluent middle class have noticed their food sources aren't trustworthy - and are doing something about it. The city's development doesn't just affect farmers. It is being driven by vast numbers of people coming to the city, many to work in the vibrant IT sector. They all need access to reliable food sources. But some people in Bangalore's affluent middle class have noticed their food sources aren't trustworthy - and are doing something about it.

Meenakshi Arun, an IT professional at Hewlett Packard, has joined a growing middle class movement who grow their own food. She says her group, Garden City Farmers, has trained more than 5,000 people in the last five years.

Media caption Meenakshi began growing chillies and other plants because she knows they're clean

But individual citizens growing vegetables on terraces and patios requires time, money and space that most people can't afford. For the traditional farmers in Ramagondanahalli, their only equity is in their land. When that land becomes less productive because of polluted water, they turn to selling.

One villager who turned from rose farmer to real estate broker is embracing the development.

Image copyright Megan Devlin Image caption Sanjeev doesn't see a future for farmers in Bangalore

Sanjeev Sanjeevappa grew up in Ramagondanahalli, but he doesn't think a farming lifestyle is feasible any more in the city. His community's farms are surrounded by high-rises for Whitefield's IT workers, and the market prices for crops are constantly in flux.

Sanjeev is young, tall and wears solid gold necklaces and rings. He says he owns 10 acres of land outside the city, 20 times what Hanumanthappa farms on, and he bought it by selling a small portion of land in Ramagondanahalli.

This struck him and he thought other farmers could do the same, so he started to broker land deals. Being a real-estate agent fetches him a lucrative commission. Typically, intermediaries like him take 2% of the selling price.

In 2012, an acre of land in Ramagondanahalli was selling at 40-60 million rupees ($618,000-$927,000; £495,000-£742,000). Today it costs double that and fetches between 80-100 million rupees ($1,235,000-$1,544,000; £989,000-£1,236,000).

He believes the only way out of agricultural instability is to bundle farmers' small plots together and sell their combined land as a package to developers. He is a farmer-turned-real-estate agent who connects farmers with builders.

"For farmers who have one-tenth of an acre of land, it is very difficult to sell it to the builders directly. So, we pool farmers who own small portions of land and collectively make them agree to sell it to builders," Sanjeev says.