Floral massing of Western Ghats

|

Avik Ray 1, Rajasri Ray 2, Ramachandra T.V 2 |

| l |

India with four diversity hotspots (among 35 global hotspots) flaunts a very unique floral and faunal assemblages. It harbours 17,527 flowering plants belonging to 2984 genera and 247 families; of which more than six thousand species are endemic (35.3% of total flowering plants from India). On the other hand, the country has 246 globally threatened floral species (i.e. 2.9% of the global estimations) (4th National Report to the CBD, 2009). The history of this biological wealth could be interrelated with Gondwana when India had been a component of the larger supercontinent from Cambrian (Geological Time Scale, Table 1).

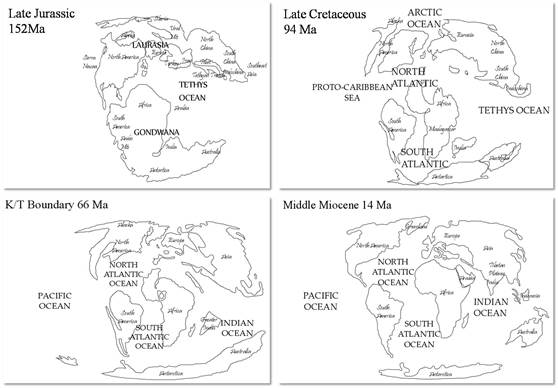

Fig 1. Gondwana breakup and movement of Indian Peninsular fragment towards Eurasia, the numbers indicate respective time of occurrence in terms of million years ago (ma); (drawing based on Scotese 2001)

In early Cretaceous the great continent fragmented into several pieces of landmasses and commenced receding away from each other. India was one such landmass headed towards north as it moved away from the other neighbours. The floating mass carried several Gondwana elements while on northward journey and these primed the initial evolution of biota across Indian subcontinent (Figure 1). Following the suturing of Indian mass to the Eurasia, there had been other events causing major biotic enrichment, e.g. climatic oscillations and geologic catastrophe. Deccan volcanism happened during Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary perhaps drove extirpation of a significant portion of floral gifts from Gondwana. In addition to geologic catastrophe, the impact of climatic oscillation had been quite severe. From the amalgamation of Indian mass to Asia, over the millions of years, throughout Eocene, Oligocene and Miocene the dispersal of biotic elements continued from neighbouring countries e.g. China-Tibet, Malaysia, Mediterranean, East Africa that gradually sculpted the finer melange of biotic elements. The final strokes had been given by Quaternary climatic perturbation i.e. so-called Ice age that exerted final impetus to floral evolution leading to extinction as well as revamping of biota. In a nutshell, there had been climatic and geologic factors which acted as prodigious selective force and filtered out the relicts of Gondwana and dispersed neighbouring elements. However, the history of floral evolution had been very enigmatic due to severity and complexity of the events and reconstruction of the past warrants an integration of disciplines e.g. geology, paleoecology, climatology, palynology, genetics.

Attributes |

Hotspots |

|||

Himalaya |

Indo-Burma |

W.Ghats and Sri Lanka |

Sundaland |

|

Hotspot original extent (km2 ) |

741,706 |

2,373,057 |

189,611 |

1501,063 |

Hotspot vegetation remaining (km2) |

185,427 |

118,653 |

43,611 |

10,0571 |

Endemic plant species |

3,160 |

7,000 |

3,049 |

15,000 |

Human population density (people/km2) |

123 |

134 |

261 |

153 |

Area protected (km2) |

112,578 |

235,758 |

26,130 |

179,723 |

Table 2. Attributes of biodiversity hotspots from India (taken from 4th national report CBD)

Western Ghats belongs to the great peninsular India which swam following the break-up of the super-continent Gondwana towards Mainland Eurasia. The history of this escarpment says its concomitant formation with the Deccan Volcanism and later floral and faunal massing over several million years. However, the riddle stays alive, whether Western Ghats still retains some of the relicts of Gondwana, if so, today’s floral legacy may be a diaspora of both Gondwana as well as members arrived from neighbouring or distant countries and flourished later.

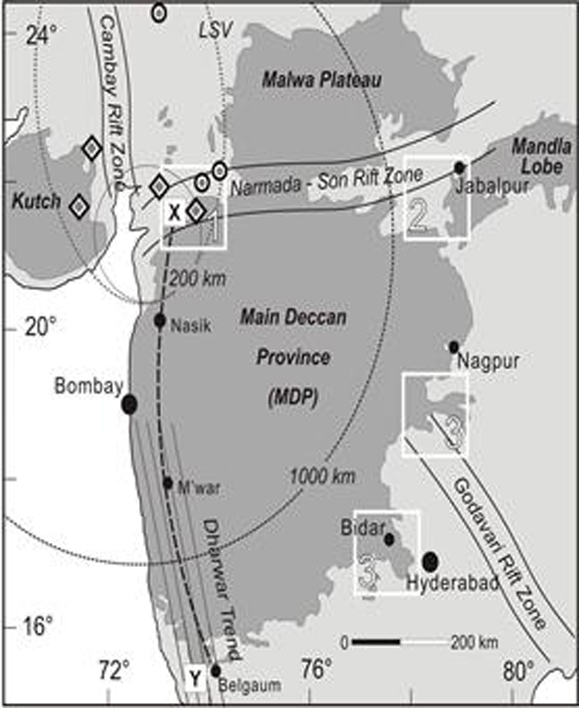

Figure 2: Shaded areas represent the current areas of expanse of Deccan trap.

Cross section line X - Y follows the Western Ghats escarpment where the lava succession is best exposed. Numbers 1 -3 (square boxes) indicate the localities of key sedimentary successions.

(http://www.geosociety.org/news/pr/07-59.htm)

Era |

Period |

Epoch |

Characteristic organisms |

Duration (m.y.) |

Began (m.y.) ago |

|

Cenozoic |

Quaternary |

Recent |

Last 5,000 years |

|||

Pleistocene |

Redistribution of floras according to retreat and advance of glaciers. Woody mammoth and giant bison. Appearance of modern human. |

2.5 |

2.5 |

|||

Tertiary |

Pliocene |

Mastodons, camels, horses and cats. |

4.5 |

7 |

||

Miocene |

Establishment of present day forest associations. Grazing mammals and apelike creatures. |

19 |

26 |

|||

Oligocene |

Widespread occurrence of now relic taxa (Metasequoia, Cercidiphyllum), true cats, dogs, rodents and rhinoceroses. |

12 |

38 |

|||

Eocene |

Many old generas of angiosperms became extinct with new modern types appearing. All modern orders of mammals present; first horses. |

16 |

54 |

|||

Paleocene |

Angiosperms continued, first lemurs; some modern groups of birds |

11 |

65 |

|||

Mesozoic |

Cretaceous |

Upper |

Angiosperms rise to dominance. Monocots and dicots present. Modern group of insects; first pouched and placental mammals; extinction of giant land and marine reptiles. |

76 |

141 |

|

Lower |

||||||

Jurassic |

Upper |

Rise of higher insects and birds. Dinosaurs abundant. |

54 |

195 |

||

Middle |

||||||

lower |

||||||

Triassic |

Upper |

Diversification of conifers and ferns. First mammals, rise of the dinosaurs. |

30 |

225 |

||

Middle |

||||||

Lower |

||||||

Paleozoic |

Permian |

Upper |

Extinction of arborescent lycopsids and sphenopsids. Diversification of reptiles |

55 |

280 |

|

Lower |

||||||

Carboniferous |

Pennsylvalian |

Upper |

Origin of confers, reptiles, diversification of amphibians, |

45 |

325 |

|

Middle |

||||||

Lower |

||||||

Mississippian |

Upper |

Spread of amphibians, sharks, and bony fish. Insects evolved wings. |

20 |

345 |

||

Lower |

||||||

Devonian |

Upper |

Diversification of vascular plants, all major groups except angiosperms, diversification of fishes, origin of amphibians. |

50 |

395 |

||

Middle |

||||||

Lower |

||||||

Silurian |

Upper |

First vascular plants. Scorpions and millipeds, first air-breathing animals. Brachiopods, corals and eurypterids |

40 |

435 |

||

Lower |

||||||

Ordovician |

Upper |

Green and red algae, First vertebrates, variety of marine invertebrates |

65 |

500 |

||

Lower |

||||||

Cambrian |

Upper |

Cyanophytes, green and red algae, marine invertebrates, |

70 |

570 |

||

Middle |

||||||

Lower |

||||||

Precambrian |

Growth of cyanophytes, red algae, bacteria and possibly green algae. |

4,130 |

4700 |

|||

Effect, which is the key driving force behind mass extinction of significant fraction of biota. Currently, in absence of detail stratigraphic records, the effect of Cretaceous volcanism on the extinction of Gondwanan elements is mostly contentious. However, reviewing the spatial extent of the volcanism it seems probable that it has mostly enveloped today’s Maharashtra, Gujarat perhaps extending to north of Karnataka sparing a larger fraction of the southern most part which may have the chance to serve as refugia. These are areas where Gondwana relicts or old migrants from Afro-Madagascar might find their refuge to tide over unfavourable condition; upon onset of the favourable period gradually propagated and established in newer patch. There has been growing evidence on southern Western Ghats as refugia during the volcanism, mostly from faunal groups (Joshi and Karanth, 2013). In addition, post-volcanism period perhaps during late Paleocene and Early Eocene rain forest refugial presence is quite conspicuous from the plethora of fossil records (Prasad et al. 2008). In short, it seems that biotic refugia survived in southern Western Ghats, may be in isolated pockets which later served as biological pump to recharge biota across the larger part of the escarpment.

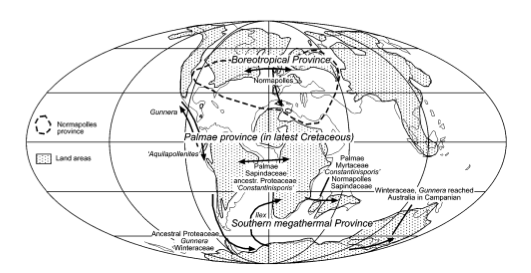

Independently of the old lineages from the super-continent, Western Ghats had presumably been massed by a diverse floral forms from the neighbouring countries or continents. This had commenced from the middle Cretaceous when India was very close to Africa and almost hooked to Madagascar which facilitated the biotic exchange between them (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Late Cretaceous paleogeography and dispersal routes of various floral elements (Smith et al. 1994)

Pollen records of various plant families makes the case of biotic exchange between India and Madagascar stronger (Morley 2003). It was facilitated by the formation of transient land-bridges acting as stepping stones for colonisation (Ali and Aitchison, 2008).

Malayan elements in the Western Ghats includes Myrtaceae, Guttiferae, Melastomataceae, Dipertocarpaceae (Mani 1974). The most dominant forms include Dipterocarpus, Vateria, Hopea, Syzygium, Eugenia, Melastoma. There is an iconic palm member endemic to WG, Benitnckia condapanna. The list may include Myristicaeae, Bambusoideae etc. (Fact sheet).

Fact Sheet

|

|

Dipterocarpus spp. Dipterocarpus spp. are iconic members of ancient Dipterocarpaceae family. India and Sri Lanka serve as secondary centre of this family while south-east Asia act as prim ary centre by having diverse representation of the species. In India, Dipterocarpus genus has 10 species distributed in Western Ghats, North-east India and Andaman-Nicobar islands characterized by having large cylindrical bole, toemtose, large stipule and winged seed. Dipterocarpus spp. are commercially important for their high quality wood and resin which led to destruction of vast amount of Dipterocarp dominated forest in tropics in earlier twentieth century. Currently the species are mostly distributed in reserve forests and protected area frameworks. A . Mature tree of Dipterocarpus indicus; B. Hairy stipule of D. indicus C. Amplexicaul stipule of D. indicus; D. Winged seeds of D. indicus |

|

||

|

|

|

Vateria spp. Vateria sp. is another iconic member of the family Dipterocarpaceae. In Western Ghats, Vateria spp. (3 species) are mostly available from central and southern Ghats region. The species is characterized by having broad lamina, white fragrant flower in terminal or axillary panicles and cylindrical fruit. This species is successfully used in the plantation program due to its high adaptability. A . Mature tree of Vateria indica; B. Inflorescence of V. indica

|

|

||

|

|

|

Hopea spp. Hopea sp. (family Dipterocarpaceae) one of the widely distributed woody endemics across Western Ghats. This species can be recognized by its tomemtose petiole (H. ponga), presence of domatia on the vein axils (H. parviflora), white/pink small flowers and winged seeds. Hopea ponga is widely planted for leaf manure supply in areca nut plantation (known as sopinabetta). The species has also wide application in construction industry. A . Tomentose petiole of H. ponga; B. leaf of H. parviflora |

|

||

|

|

|

|

Syzygium spp. Syzygium sp. one of the widely spread genera of Myrtaceae family. In Western Ghats, an approximate 35-38 species have been reported although taxonomic disputes complicate the claim further. Syzygium can be characterized by its intra-marginal venation, cup-shaped calyptra, numerous stamens and edible berries. Some commercially important members are S.cumini, S.aromaticum, S.samarangense A . Intramarginal venation in S. heyneanum; B. Flowering tree of S. hemisphericum; |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bentinckia condapanna. Bentinckia condapanna (family Arecaceae), one of the endemic palms of Western Ghats. The species is noted due to its rocky cliff habitat in evergreen forests of southern Western Ghats. This member morphologically can be distinguished by solitary stem (10 mt. tall and 15 cm. diameter), Leaves arching, inflorescences borne below the leaves, fruits globose, brown, 1.5 cm in diameter. The inner core and growing bud (known as palm heart) is edible for animals (e.g. elephants). A . Hill slopes with B. condapanna (image: P. Jeganathan); B. Inflorescence of B. condapanna (image: Divya Mudappa); C. Young fruits of B. condapanna (image: R. Sundaram) |

|

These members mostly have their centers of diversity in Malayan archipelago and around. The dispersal into India perhaps had happened during Eocene, Oligocene, and Miocene times. There could be common migration routes through the north-eastern corridor; or even the case of long distance trans-oceanic dispersal of certain elements is also possible. However, the conspicuous presence of many remnant conspecific or sister lineages across north-east may strengthen the possibility of a dispersal route facilitating plant migration.

Foothills of Himalaya shelter a few cold-loving members which are found at the middle to higher elevation across WG and Nilgiris; e.g Ericaceae, Asteraceae, Rubiaceae. These are the lineages which perhaps invaded WG from north and established, the colonization perhaps maintained the continuous vegetation cover through the central India. However, fragmentation due to change in climate change during Quaternary period majorly delinked the floral connection existed. The discontinuous distribution of these biotic elements today portrays a pattern called central Indian disjunction and evokes of relictual absence of a few shared taxa in once-lush cover maintained perhaps during the pre-Quatarenary times.

Several lineages are abundant across Western Ghats e.g. Hernandia, Lindenbergia, Pittosporum, Acrotrema, Gomphandra, Nothopodytes, Sarcostigma, Hydnocarpusetc. which have their congeners in Africa or South America. In addition, there are members of Orchidaceae, Poaceae (Andropogoneae) which also occur in Africa. These perhaps resurrect the ancient Gondwanan link i.e. relicts imbibed with the signatures of past events and depict independent evolution of several families shared among the participating countries of Gondwana super-continent. So, these taxa retain the Gondwana heritage perhaps were able to tide over the unfavourable periods of Deccan volcanism restricting themselves in isolated refugia. In contrast, with growing cases of long-distance trans-oceanic dispersal from various families, the chance of migration from distant place and establishment of a few taxa can not be ruled out.

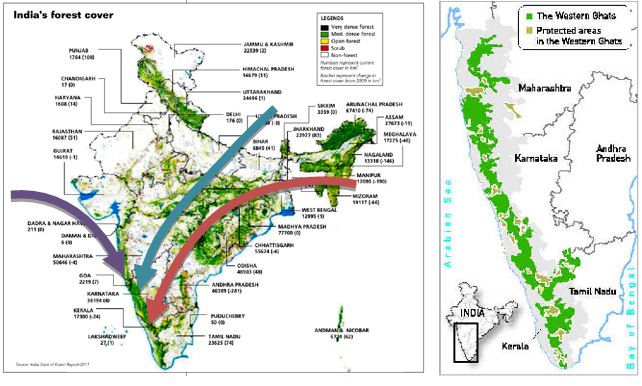

Figure 4: schematic representation of probable dispersal routes of flora over the evolutionary timescale

In summary, the evolutionary history of enormous floral diversity of Western Ghats appears as highly complicated. It seems that it has been primarily crafted by gifts from Gondwana, and later enriched by plethora of dispersal events over millions of years (Figure 4). Many taxa may have arrived from Afro-Madagascar when India was lying close enough to support biotic exchange. Others could have been following the route through north-eastern landscapes leaving their sisters in Malaya. A few invaded from north and foothills of Himalaya or even from further north i.e. Qinghai Tibetan Plateau. In addition, trans-oceanic dispersal of floating seeds or fruits traversing boundaries of seas and oceans also contributed majorly to floral enrichment throughout the world, and Western Ghats may not be an exception (de Quieroz 2005). Not the least, yet another key period in earth’s history that governed major rearrangement of distribution of biota is the Quaternary age; long term changes in earth’s orbit caused a massive climatic and geological upheaval i.e. repeated glaciations and deglaciations. This in turn recreated the distribution pattern, fuelled diversification and lastly speciation. In a nutshell, it appears that over millions of years, a melange of climatic and geological factors together with dispersal gave rise to major floral diversity of Western Ghats. In order to decipher the complex web of movements, an understanding of the age of the members, their relations with global congeners, and past dispersal routes are complementary to each other.