Common lands are the resources accessible to the whole community of a village with no exclusive property rightsto any individuals. These include village pastures (Gomala), community forests, wastelands (Karab lands), common threshing grounds, streams and watershed drainages, village ponds, tanks, rivers/rivulets, riverbeds, etc. (Jodha, 1986; 2009). These lands have to be managed judiciously in a sustainable manner to ensure sustenace of resources for common good of the people.These community lands are valuable assets and protecting these lands is vital to maintain the natural drainage patterns, forest cover, environment and for other public purposesand hence constitutes a critical livelihood resource for landless, small and marginal farmers. According to Section 67 of the Karnataka Land Revenue Act, 1964, all common lands are the property of the State Government and not the property of any individual or aggregate of persons.Section 71 empowers the Survey Officers and the Deputy Commissioner to set apart lands that are the property of the State Government for free pasturage for village cattle, for forest reserves or for any other public purposes. However, with the growing demand of burgeoning population and lack of knowledge among the post-independence Indian administrators (about common lands significance), these lands are being converted for other useswithout seeking the approval of local stakeholders. Thus, degradation and deprivation of common lands have been affecting the livelihood of dependent population.

Common lands such as gomala, minor forests, etc. have played vital role in sustaining rural livelihoods, evident from 60% of India’s rural population dependent on animal husbandry in dry lands. Livestock is complimentary to agriculture, which involves an efficient use of agriculture residues (water, straw, leftovers from other crops), agriculture waste (weeds and grass, oil cakes) and convertion to manure, which helps in improving soil fertility, while productively employing surplus labour. Non-quantifiable benefits of livestock include social, religious and cultural aspects. In addition, about 15 million bullock carts fulfil two-thirds of India’s transportation needs and provide employment to 20 million people (Ramanajum, 1993).The presence of common grazing lands (gomala) in villages has helped landless and marginal farmers’livelhood through livestockrearing. Hence, to sustain rural livelihood necessitates the protection and sutainable management of common lands.

Role of commonlands in the protection of National Parks: Protected areas (PAs) and national parks (NPs) have helped in the conservation of biodiversity worldwide (Gaston et al., 2008). Most NPs and PAs are embedded in heterogeneous landscapes which are affected by forest fragmentation due to senseless anthropogenic activities involving road construction, hunting, grazing, agriculture, commercial plantations, fire, invasive species, over harvest of non-timber forest products and mining (Hansen & DeFries, 2007). Common lands such as gomala, kharab forest lands, etc. in the vicinity of PAs and NPs play crucial role in preventing deforestation, provide fodder and food, etc. These buffer regions help in conserving biodiversity of a variety of species, communities and ecosystems. The conservation of PA or NP ecosystemsdepend on the status of buffer region (Chazdon et al., 2009). Understanding the status of tropical diversity and anthropogenic pressure on PAs and other forested regions requires studying patterns of biodiversity in adjoining landscapes which are actively managed and modified by humans for a wide variety of traditional and commercial purposes, including hunting, agriculture and plantations of native or exotic species. The diverse landscapes with tree cover (as forest fragments, fallow land, riparian areas, live fences, dispersed trees, or shade canopies) provide complementary habitats, resources, and landscape connectivity (e.g., Harvey et al. 2006; Sekercioglu et al. 2007). The natural vegetation regions or grass lands with dispersed trees surrounding protected areas also support significant levels of biodiversity (Mayfield et al. 2005; Barlow et al. 2007) and also provide valuable ecosystem services, such as carbon sequestration, hydrological protection (Tschakert et al. 2007). Grassland ecosystems with high levels of productivity and energy utilization support large populations of grazing animals.Grasslands and community reserve lands are ecologically and economically treasured biomes used for livestock and small herbivore grazing. Livestock constitutes the backbone of agrarian economy and its sustenance depends on the grasslands.

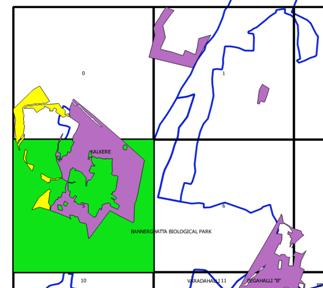

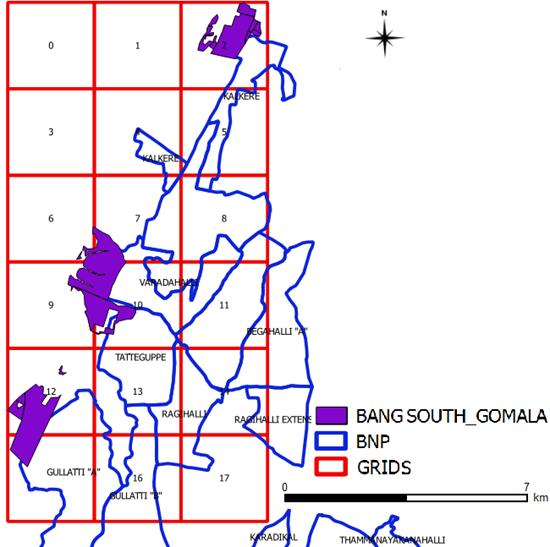

The encroachmentof cmmon lands with the substantial changes in vegetation structure are induced by humans for cultivation, mining, etc. (Hirota et al. 2011). The restoration of these habitats (Daryanto and Eldridge, 2011), provide opportunities for biodiversity conservation.Buffer regions (with common lands) helps in mitigating the anthropogenic disturbances including instances of fire, etc. in NP, PAs and forests. These lands also act as a natural corridor for animal migration in fragmented area provide critical habitats and refugia for biodiversity.Encroachment of forest land and other government lands such as gomala, kharab lands has been threatening species in PAs and in forest patches. The land degradation due to illegal mining, uncontrolled grazing, etc. will suppress natural regeneration and increses the extent of invasive species such as lantana, eupatorium, parthenium, etc.Incorporation of ‘biodiversity friendly’land uses into actively managed buffer zones or biological corridorscontributestowards the longterm conservation value of protectedareas (DeFries et al. 2007; Harvey et al. 2008). Buffer regions with intact forests, agroforestry, remnantvegetation, plantations, and managed forest patches provide criticalhabitats and refugium for biodiversity (Harvey and DeFries, 2006; Harvey and Gonz´alez 2007; Bhagwat et al. 2008). This emphasises the need for diversely managed habitats surrounding PA’s (DeFries and Rosenzweig, 2010), especially in areas with high population pressure. Therefore, maintaing the gomala and kharab forest regions in and arround PAs, NPs is vital for adding value to mainstream conservation endeavours.The Bannerghatta national park and its environ (1 km) has arround 8938.56 ha of governemt lands in the form of gomala, kharab-forest, kharab land etc. These lands aid as a corridor for various faunal species,which also maintaing rich biodiversity. The gomala and kharab forest lands under the ownership of state helps to meet the livestock fodder demand, but unfortunatly these ecologically important lands are being encroached. National Commission on Agriculture (1976) had declared encroachment as unauthorized occupation leading to the significanct degradation and emphasizes the need for legal protection.

State Government and the Central Government can acquire land for the various purposes mentioned under the List I and II of the Seventh Schedule of the Indian Constitution. The British Government first outlined the Regulation 1 of the Act in 1824 which was then applied throughout the Bengal provinces. This Act enabled the government to acquire immovable property or land at a ‘fair and reasonable’ price for any public purpose like construction of roads, canals, etc. The term “appropriate government” in the LA Act, 1894 would refer to both the Central and State governments, depending on which of them issues a notification under Section 4 for the acquisition of land. Under Article 31(2) of the Constitution, State can acquire land only for the ‘Public Purpose’. The term “appropriate government” in the LA Act, 1894 would refer to both the Central and State governments, depending on which of them issues a notification under Section 4 for the acquisition of land. Under Article 31(2) of the Constitution, State can acquire land only for the ‘Public Purpose’. Acts such as “Acquisition of land for Grant of House Sites Act, 1972 (Karnataka Act 18 of 1973); Acquisition of Land for Grant of House Sites Rules, 1973help in acquisition. In BNP environ the revenue lands, gomala lands (regions were earlier used as a grazing lands by villagers) were acquired by BDA (Bangalore development authority) for creating settlements and layouts which woul deprive the livelihood option (livestock rearing) of local people. Plan to construct housing layouts by BDA only highlights the agencies insensitiveness and continued irresponsible unplanned action, which would only lead to higher instances of human-animal conflicts.

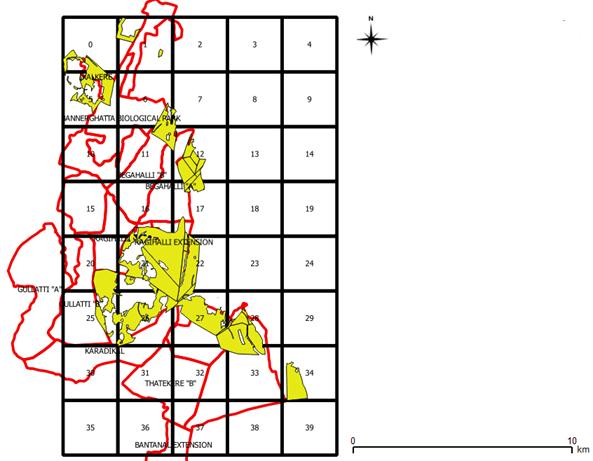

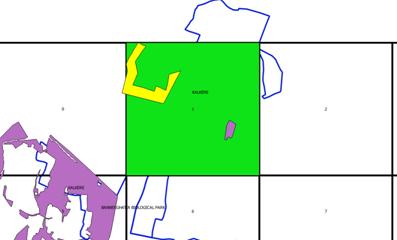

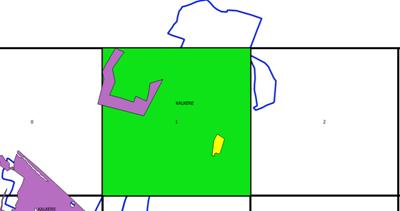

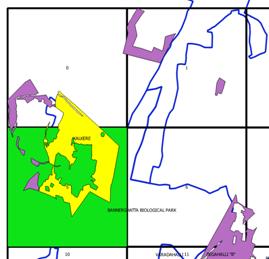

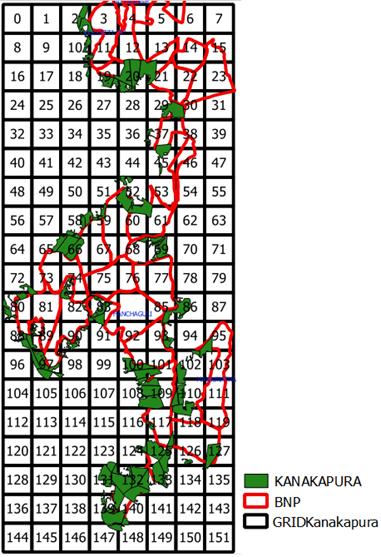

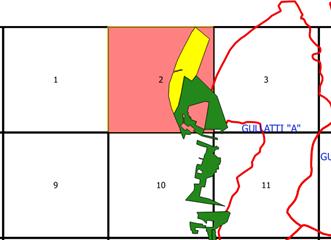

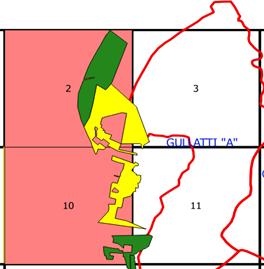

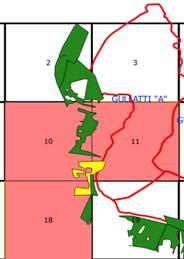

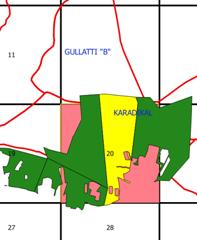

This section provides the spatial extent of gomala and the extent of encroachments in 1km buffer region of BNP, apread across three taluks. The spatial analysis involved (i) base map preparation, (ii) temporal remote sensing data analysis, and (iii) identification of different types of encroachment, data analyses, etc. Figures 1.1 and 1.2 depict gomala of Ragihalli. Spatail data of forest boundaries, gomala lands, forest plantation, etc. provided by the Krnataka Forest department were overlaid on temporal remote sensing data. Encroachment of gomala lands were identified and delineated with the help of Google Earth (http://google.earth.com) data. The maps highlighting different categories of encroachment, separately for three taluks of BNP has been created and analysed. Figure1.1 highlights gomala land status in Ragihalli region of Anekal taluk (survey number 69) with good native flora and grasses.On other hand, Figure 1.2 shows highly degraded gomala, kharab forest land in Guttal hunase village, Kanakapura taluk.Gomalalands in and arround BNP with diverse grasses and other vegetation supports BNP biodiversity (Figure 1.3). The rampent sand mining and land conversions (Figure 1.4 and figure 2) for agriculture, human settlements and commercial plantations have degraded and affected grasslands ecology. Immature decisions of regularising encroachments has encouraged the local land mafia to further encroach gomala and kharab forest lands in and arround BNP. Rampant sand mining or ‘filter sand’ is common in entire BNP region and its environs. Uncontrolled expansion of agricultural land is leading to the erosion of soils, decline in soil fertility, reduced quality and quntity of water.Rampant livestock grazing in BNP has affected the forest regeneration. Cattle grazing is one of the major problems in the management of forest and wildlife. The human-elephant conflict is one of the serious threats to the survival of Asian elephants in BNP. Table 1 and Figure 3 lists the extent of encroachment of common lands in he respecive taluks.

|

Figure 1.1: View of gomala land (survey number 69) in Ragihalli region |

|

|

Figure 1.2: View of gomala land in Guttala Hunase, Kanakapura taluk, rampent fuelwood collection is noticed. |

|

Figure 1.3: Pugmarks of wild boar, spotted deer in gomala land of Shivanhalli region and elephant dung noticed in Mantapa village gomla survey number 156 |

|

Figure 1.4: Filter sand peparation in Therubeedhi village, Kanakapura Taluk survey numbers 66& 106 |

|

Figure2: Illegal mining of soil for sand making in survey number 96 gomala land of J.I.Begganadoddi village, Anekal taluk, Bangalore (Urban) District. |

S.No. |

Taluk |

Govt. Land form |

Area (Ha) |

Total area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

Total area of encraochment (Ha) |

1 |

Anekal |

Gomala land |

1474.15 |

2300.02 |

876.38 |

1422.88 |

Kharab-Forest land |

359.2 |

169.98 |

||||

Kharab land |

466.67 |

376.52 |

||||

2 |

Bangalore south |

Gomala land |

665.37 |

753.68 |

427.95 |

516.26 |

Kharab-Forest land |

0 |

0 |

||||

Kharab land |

88.31 |

88.31 |

||||

3 |

Kanakapura |

Gomala land |

3491.19 |

5884.86 |

2152.69 |

3716.03 |

Kharab-Forest land |

1602.44 |

1049.46 |

||||

Kharab land |

791.23 |

513.88 |

||||

Total area (Ha) |

8938.56 |

Encroachment in total (Ha) |

5655.17 |

|||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number& type |

Co-ordinates (Latitude, Longitude) |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

|

1 |

1 |

Bilvaradhahalli, Jigani (Hobli), Anekal (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) District. |

7; KHARAB |

12.828 77.572 |

Stone crusher |

Settlements |

39.59 |

4.61 |

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number& type |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

||||||||||||||

2 |

1 |

Gollahalli .N, Jigani (Hobli), Anekal (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) |

22; KHARAB |

12.821 77.587 |

Settlements |

5.16 |

5.16 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number& type |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

||||||||||||||

3 |

5 |

Bhoothanahalli, Jigani (Hobli), Anekal (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) District. |

64; KHARAB- forest land |

12.811 77.562 |

Stone crusher |

Agriculture |

190.15 |

30.89 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number& type |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

||||||||||||||

4 |

0, 5 |

Bhoothanahalli, Jigani (Hobli), Anekal (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) |

67; KHARAB - FOREST |

12.819 77.547 |

Settlements |

Agriculture |

30.20 |

30.20 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Sno. |

Grid no |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates (Latitude, Longitude) |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

1 |

2 |

Pillaganahalli, Uttarahalli (Hobli), Bangalore south (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) |

1; GOMALA |

12.8430 77.5798 |

BDA allotment-Weaver’s colony |

80.56 |

80.56 |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Sno. |

Grid no |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

2 |

2 |

Pillaganahalli, Uttarahalli (Hobli), Bangalore south (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) |

2; GOMALA |

12.8501 77.5832 |

BDA allotment-Weaver’s colony |

13.02 |

13.02 |

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Sno. |

Grid no |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

|

3 |

3 |

Gottigere, Uttarahalli (Hobli), Bangalore south (taluk), Bangalore (Urban) |

112; GOMALA |

12.8460 77.5850 |

BDA allotment-Weaver’s colony |

4.92 |

4.92 |

|

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates (Latitude, Longitude) |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

|

1 |

2 |

Bettahallikaval, Harohalli(Hobli),Kanakapura (taluk),Bangalore (Rural) |

1; GOMALA |

12.7378 77.5169 |

Agriculture |

Settlements |

79.63 |

32.57 |

|

|

|||||||

|

|

|||||||

S.no |

Grid |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment |

|||

2 |

2, 10 |

Gottigehalli, Harohalli(Hobli),Kanakapura (taluk),Bangalore (Rural) District. |

77; GOMALA |

12.7239 77.5198 |

Settlements |

Agriculture |

169.99 |

156.35 |

||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

S.no |

Grid no. |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

|||

3 |

10, 11, 18 |

Kadjakkasandra, Harohalli(Hobli),Kanakapura (taluk),Bangalore (Rural) District. |

49; KHARAB |

12.7024 77.5212 |

Sand mining |

Agriculture |

40.05 |

40.05 |

||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

S.no |

Grid |

Village details |

Survey number |

Co-ordinates |

Encroachment type |

Area (Ha) |

Area of encroachment (Ha) |

|||

4 |

20 |

Bilaganakuppe, Maralawadi(Hobli),Kanakapura (taluk),Bangalore (Rural) District. |

44; KHARAB |

12.6927 77.5584 |

Agriculture |

188.51 |

71.21 |

|||

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||

Recommendations:

Suggestions to protect the integrity of common lands (gomala, kharab, kharb forest land) to sustain livelihood of dependent biota are:

Wild woody plants that provide food for wildlife and recommended for selective planting in grasslands

| Sl. |

Species |

Local/common Name |

Parts eaten and wild animals feeding on them |

Remarks |

1 |

Acacia concinna |

Seege |

Pods-Deer*, Sambar, Gaur |

|

2 |

Acacia ferruginea |

Banni |

Pods-Deer*, Sambar, |

|

3 |

Artocarpus integrifolia |

Halasu, Jack |

Fruits-Monkeys, Bear Leaves- fodder |

Fallen fruits of A.integrifolia and A.hirsutus are relished by many ungulates |

4 |

Bauhinia sp. |

Basavanapada |

Pods- Gaur, Sambar, Deer* |

|

5 |

Bombax ceiba |

Buraga, Silk cotton |

Flowers-Monkeys, Sambar, Deer*, Wild pig. Nectar for many birds |

|

6 |

Careya arborea |

Kumbia, Kaul |

Bark-Sambar, Fruits-Elephant, Monkey, Porcupine, Sambar |

|

7 |

Cassia fistula |

Kakke |

Pods-Bear, Monkeys |

|

8 |

Cordia macleodii |

Hadang |

Fruits- Deer*, Gaur, birds |

|

9 |

Cordia myxa |

Challe |

Friuits-Deer*, Sambar, Bear, birds |

|

10 |

Dillenia pentagyna |

Kanagalu |

Fruits-Deer*, Sambar, Gaur, birds |

|

11 |

Ficus spp. |

Atti |

Fruit- Birds, including Hornbills, bats etc., and ungulates such as Deer*, Sambar, etc. Leaves- fodder for herbivores |

Keystone species with one or the other tree flowering throughout the year and eaten by large number of wild animals, both big and small |

12 |

Grewia tiliaefolia |

Dhaman; Dadaslu |

Leaves-Sambar, Deer*,Fruits-Monkey, birds |

|

13 |

Hydnocarpus laurifolia |

Suranti; Toratte |

Fruit-Porcupine |

|

14 |

Spondias acuminate |

Kaadmate |

Fruits: Sambar, Porcupine, Deer* |

|

15 |

Kydia calycina |

Bende |

Leaves –Ungulates |

Seems to be eaten by ungulates as they are eaten by cattle. |

16 |

Moullava spicata |

Hulibarka |

Fruits-Deer*, Sambar |

Flowering spike is also eaten |

17 |

Mucuna pruriens |

Nasagunni kai |

Leaves-Deer* |

|

18 |

Phyllanthus emblica |

Nelli; Gooseberry |

Fruits-Sambar, Deer* |

|

19 |

Strychnos nux-vomica |

Kasarka |

Fruits- pulp eaten by monkeys, Hornbills |

|

20 |

Syzygium cumini |

Nerale |

Fruits- wild Pig, Deer*, Bear and several birds |

|

21 |

Tectona grandis |

Saaguvani; Teak |

Bark- Elephants. |

Elephants debark the tree in long strips and consume it. |

22 |

Terminalia belerica |

Tare |

Fruits-Deer, Sambar |

|

23 |

Tetrameles nudiflora |

Kadu bende |

Bark-Elephants |

Favourite tree for bees to make hives |

24 |

Xylia Xylocarpa |

Jamba |

Seeds-Gaint Squirrel, Monkeys |

|

25 |

Zizhiphus oenoplia |

Fruits-Jackels, Procupine, Deer*, Pangolin, birds |

||

26 |

Ziziphus rugosa |

Kaare |

Fruits-Bear, birds |

*Deer includes Mouse deer, Barking deer, Spotted deer

References: