Sudarshan P. Bhat1, G.R. Rao1, Vishnu Mukri1, Bharath H. Aithal1, Vinay S.1, M.D. Subash Chandran1,3 and T.V. Ramachandra1,2,* |

| l |

Forests are a precious gift of nature and need to be protected and managed for the sustained production of natural resources such as timber, firewood, industrial raw materials for making paper, rayon and minor forest produce like honey, wax, soap nut, medicinal plants etc. Forest ecosystems have an important bearing on the ecological security and people’s livelihood. These ecosystems preserve the physical features, minimize soil erosion, prevents floods, recharge groundwater sources, check the flow of subsoil water and help to maintain the productivity of cultivated lands.

HISTORY OF FOREST MANAGEMENT IN SHIMOGA

The Western Ghats is one among the 34 global hotspots of biodiversity and it lies in the western part of peninsular India in a series of hills stretching over a distance of 1,600 km from north to south and covering an area of about 1,60,000 sq.km. It harbours very rich flora and fauna and there are records of over 4,000 species of flowering plants with 38% endemics, 330 butterflies with 11% endemics, 156 reptiles with 62% endemics, 508 birds with 4% endemics, 120 mammals with 12% endemics, 289 fishes with 41% endemics and 135 amphibians with 75% endemics (http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/ces_tr/TR122/index.htm).

The rich biodiversity coupled with higher endemism is due to the humid tropical climate, topographical and geological characteristics, and geographical isolation (Arabian Sea to the west and the semiarid Deccan Plateau to the east). The Western Ghats forms an important watershed for the entire peninsular India, being the source of 37 west flowing rivers and three major east flowing rivers and their numerous tributaries. The stretch of Central Western Ghats of Karnataka, from 12°N to 14°N, from Coorg district to the south of Uttara Kannada district, and covering the Western portions of Hassan, Chikmagalore and Shimoga districts, is exceptionally rich in flora and fauna. Whereas the elevation from 400 m to 800 m, is covered with evergreen to semi-evergreen climax forests and their various stages of degradation, especially around human habitations, the higher altitudes, rising up to 1700 m, are covered with evergreen forests especially along stream courses and rich grasslands in between. This portion of Karnataka Western Ghats is extremely important for agriculture and horticultural crops. Whereas the rice fields in valleys are irrigated with numerous perennial streams from forested hill-slopes the undulating landscape is used to great extent for growing precious cash crops, especially coffee and cardamom. Black pepper, ginger, arecanut, coconut, rubber are notable crops here, in addition to various fruit trees and vegetables. Some of the higher altitudes are under cultivation of tea. From the point of productivity, revenue generation, employment potential and subsistence the central Western Ghats are extremely important (http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/energy/water/paper/environmental_survey2011_gundia/index.htm).

Trends of forest areas in Mysore presidency: The Mysore forest department was formed in 1864. Land utilization trends have changed dramatically in Mysore presidency during the post-Forest Act period. Available data indicates an increase in forest cover from 36.35 lakh hectares (in 1893–1894) to 52.55 lakh hectares (in 1915–1916). It has further gone up to 53.45 lakh hectares in the subsequent decade. It remained more or less the same for the rest of colonial period. In other words, the proportion of forest area has witnessed a marginal increase from 15.57 per cent of the total geographical area in 1884–1885 to 16.40 per cent in 1946–1947.Land not available for cultivation which has risen from 44.92 lakh hectares in 1884–1885to 96.07 lakh hectares in 1910–1911, however, this has declined in the subsequentdecades. In 1946–1947, it has come down to 56.88 lakh hectares (Mysore Forest Administrative Report, 1893-1956).

Forest Management / Timber extraction: In the past, the importance was given mainly to selection felling and improvement felling with the primary objective of revenue collection. Timber was mainly brought to the depots for sale.Historical records show that there was no separate system to look after forest management and operation in felling of trees until the British time. Free access to hack and burn forests at will for kumri cultivation appears to be a wide spread practice through out the Ghats. Ruling classes generally exercising power over selected species of trees by reserving them to the crown and prohibiting public from felling them. The privilege was sold in auction and leases to traders, who were then given access to forests to cut and remove timbers (Mysore Forest Administrative Report).

Expansion of agriculture: Expansion of agriculture was notable in the Mysore Presidency during the post-Forest Act period. Despite an increase in current fallows, the net sown area has gone up progressively during this period. For instance, in 1884–1885, 86.33 lakh hectares of land was the net sown area and it has shot up to 125.59 lakh hectares in 1946–1947. In other words, the proportion of net sown area, which was 37 per cent of the total geographical area in 1884–1885, had risen to 39.05 per cent in 1946–1947. This highlights that more and more land was brought under the cultivation during the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries in the Mysore Presidency (Mysore Forest Administrative Report, 1893-1956).

At the beginning of the 19th century, unbroken forest covered the Western Ghats from near the sea front to the most elevated ridges. During the British rule the tree felling and smuggling were common. Within the 30 to 40 years, forests declined from the coast to within a few miles of Western Ghats. During 19th century, forests were free for all, to cut and carry, to hack and burn to raise food crops for the pasturelands. This practice was carried extensive at the time of arrival of British especially around the Ghats regions. The forest was an obstruction to agriculture. Their whole policy was to extend the agriculture and which destroy the forests to make way. In addition to that, large areas were set apart for the rights and privileges of cultivators to meet the requirements of grazers and villagers. In the middle of 19th century, the forest decline extensively which lead to setup the management of forests began. Kumri cultivation received serious attention of the government for the extraction of forest products butit was permitted in less populated and inaccessible areas.

During the 20th century, the forest was organized very systemically. Working plans of sorts were prepared for very small and commercially attractive pockets of the reserved forests. Steam engines, the diesel locomotive and two great world wars had debilitating effect on the forests. Government monopolized the timber to the exclusion of local people who had sufficient resources in unorganized forest areas. The local people had access to the forest for the removal of thatch grass, leaf mulch for agriculture, grazing, collection of minor forest produce etc were scrutinized and unsuccessful attempts were made to bring down the pressure on the forests.

Extensive areas were also clear felled for the regeneration purpose. Simultaneously selection felling to feed open market also continued. In spite of this, attempts were made to bring more and more forest areas under working plans and work them under selection, conversion and coppice systems. Areas, which were inaccessible, were assigned to protection working circle. Demand for railway sleepers was the first major Industrial demand on forest. Patches of forests, which had good stock of mature trees, wereworked very intensively. Due to development, number of new demands for telephone ploes, electric poles, plywood, match wood, pulpwood etc also added after independence. Many private agencies had an access to the forest and many agencies had also access to the forest at the same time.

TYPES OF FORESTS IN SHIMOGA

The Malnad region of Shimoga is characterized by mountains with heavy rainfall, covering Thirthahalli, Sagar, Sorab and Hosanagara taluks. The semi-malnad regions comprising Shimoga, Bhadravati and Shikaripur taluks lie in the eastern part having vast stretches of plain lands with low and rising hillocks with low vegetation (Shimoga district Gazetter, 1975). The western side of the district is a very mountainous area and is part of the Western Ghats.

The Shimoga district has a rich and varied flora, the major contributing factors to this variety being differences in rainfall and topography within the district. In the region of the Western Ghats, the rainfall is heavy, Agumbe receives an annual average rainfall of 8,275 mm. As one proceeds to the east, the rainfall decreases very rapidly, evident from Honnali getting annual rainfall of about 600 mms. Therefore, a rapid transition from evergreen flora to the scrub type, i.e., from mesophytic to xerophytic vegetation occurs as one moves from the west to the east. Magnificent evergreen flora covers a narrow belt in the Western Ghats and it gradually merges into the moist deciduous towards the east and south. The far eastern and northern portions are scrubby and comparatively little wooded. The forests of Shimoga district consists of Evergreen and Semi-Evergreen climax forests and degradation type and deciduous climax forests and degradation type (Pascal et.al, 1982).

The Evergreen and Semi-Evergreen climax forests and degradation type consists following categories: Dipterocarpus indicus- Humboldia brunonis- Poeciloneuron indicum type, Dipterocarpus indicus- Diospyrus candolleana- Diospyros oocarpa type, Dipterocarpus indicus-Persea macrantha type, Persea macrantha-Diospyros spp.-Holigarna spp. type, Diospyros spp.- Dysoxylum malabaricum-Persea macrantha Kan forest type of low elevation (0-850m). The secondary or degraded type contains secondary moist deciduous forests. The Deciduous climax forests consist of moist deciduous type-Lagerstoemia microcarpa-Tectona grandis-Dillenia pentagyne type and dry deciduous-Anogeissus latifolia –Tectona grandis-Terminalia tomentosa type.

Evergreen and Semi-evergreen belt: The evergreen forest is confined to the west of the district with magnificent tree vegetation. Many of the hills are covered with heavy forests while valleys and ravines produce luxuriant trees known for their great height and size. Typical patches of evergreen and semi-evergreen forests occur in places like Hulikal, Kodachadri, Nittur, Nagavalli and Jog along the Western Ghats at an elevation upto 800 m receiving a rainfall of more than 200cm. Based on the average height attained by the floristic elements, the vegetation in these forests shows a 3-tiered arrangement (Ramaswamy et.al, 2001; Pascal et.al, 1982).

- Top canopy or emergent layer: This layer consists of trees which are 25-40 m or more tall with their crown raised from the general canopy surface. Some of important species are Dipterocarpus indicus,Vateria indica, Artocarpus hirsuta, Hopea parviflora, Mesua ferrea,Artocarpus integrifolia, Mangifera indica, Machilus macrantha, Michelia champaca, Alstonia scholaris, Hopea wightiana, Diospyros ebonum, Lagerstroemia sp. Syzygium canarensis etc.

- Middle canopy: This is the second layer represented by medium sized trees of height of 12-20 m. They are adapted to sub-canopy conditions. Some of the important species in this layer are Aporusa lindleyanea, Chrysophyllum roxburghii, Holigarna arnottiana, Stereospermum personatum, Strychnosnux-vomica, Vitex altissima etc.

- Lower canopy: This is the layer consisting of innumerable number of woody shrubs and small trees of average height of 3-12 m. The important floristic elements are Clerodendrum viscosum, Callicarpa tomentosa, Grewia tiliifolia, Rauvolfia densiflora, Saraca asoca etc.

Moist deciduous forest belt: The moist deciduous forest is found in the extreme north of Sorab taluk extending towards south. These types of forests are found in regions where the altitude ranges from 600-1000m and the annual rainfall varies from 150-350 cm. The width varies from belt 16 to 64 or 82 kms. It includes the timber producing forests and much sandalwood. In this belt, one can observe the Kans of Sorab and the rich fields of Sagar, Nagar and Tirthahalli. The prominent moist deciduous species of this belt are sagwvani (Tectonagrandis, Linn. f.), beete (Dalbergialatifolia, Roxb.), honne (Pterocarpusmarsupium, Roxb.), matti (Terminaliatomentosa, W. & A.), Jambe (Xyliadolabriformis, Benth.), hunal(Terminaliapaniculata, Roth.) , Nandimara (Lagerstroemia lanceoIata, Wall.), bage (Albizzialebbeck, Benth.), bilwara (Albizziaodoratissima, Benth.), tadasale (Grewiatiliaefolia, Vahl.), gandha-garige (Toonaciliata, Roem.), kadavala (Anthocephaluseadamba, Miq.), bileburuga (Geibapentandra, Gaertn.), mashe (Alseodaphnesemicarpifolia, Nees.), tare (Terminaliabellerica, Roxb.), kanagalu (Dilleniaindica, Linn.), srigandha (Santalum album, Linn.), and others.The eastern limit of this belt commences near Anavatti in thenorth and runs south-east to half-way between Shikaripur and Honnali and thence due south to Sakrebyle from where it runs due east. Along the western confines, trees proper to the ever-green forests occur frequently(Pascal et.al, 1982, Ramaswamy et.al, 2001).

Dry deciduous forest belt: The dry deciduous forest belt lies to the east of the mixed Dry deciduous deciduous forest belt in the district. The tree vegetation in this belt part is much inferior and the trees are of smaller growth. Dry deciduous species met with in this area are dindiga (Anogeissuslatifolia, Wall.), ippe (Bassialongifolia, Macbride.), kalnara (Hardwickiabinata, Roxb.), bevu (Azadirachtaindica, A .. Juss.), dale (Terminaliachebula, Retz.), nelli (Emblicaofficinalis, Gaertn.), srigandha (Santalum album, Linn.), and others. Among the thorny forest species are honge (Pongamiapinnata, Pirre.) ,seetaphala (Anonasquamousa, Lin.), antavala (Sapinduslaurifolias, Vahl.), karigeru (Semicarpusanacardium, Linn. f.), hunase (Tamarindusindica, Linn.), kare (Randiadumetornm), urimullu (Zizyphusoenoplia), bilijali (Acacia leucopholea), karijali (Acacia nilotica) (Ramaswamy et.al, 2001)

Scrub forests: These types of forests are found in eastern part of the district, with a low rainfall (less than 75 cms). These forests consist of thorny species interspersed with a few malformed deciduous trees. In most places these types of forests are converted into agricultural lands. Some of the tree species of this forest are Bauhinia racemosa, Casssia fistula, Catunaregamspinosa, Diospyrosmontana, Flacourtiaindica, Phyllanthusemblica, Santalum album, Zizipussp, Asparagus racemosus, Blepharisasperrima, Hemidesmusindicus etc (Ramaswamy et.al, 2001). Table 1 lists endemic species of Shimoga district (Radhakrishna et.al, 1992)

Table 1: Endemic species of Shimoga district (Radhakrishna et.al, 1992)

| S.No. | Species | Occurance |

| 1 | Adelocaryumcoelestinum | Yedur |

| 2 | Adenoonindicum | Kodachadri hills |

| 3 | Aeschynanthusperrottetii | Hosagadde |

| 4 | Aglaiacanarensis | Kodachadri |

| 5 | Aglaialawii | Hulikal |

| 6 | Andrographisovata | Nittur, Induvalli |

| 7 | Anisomelesheyneana | Nagavalli |

| 8 | Aporusalindleyana | Sampekatte, Yedur, Jog |

| 9 | Argostemmacourtallense | Hulikal |

| 10 | Argyreiapilosa | Sampekatte |

| 11 | Asystasiadalzelliana | Sampekatte, Nittur |

| 12 | Atylosialineata | Kundadri, Yedur, Kodachadri |

| 13 | Blachiadenudata | Jog |

| 14 | Blepharisasperrima | Yedur, Kodachadri, Hulikal |

| 15 | Blepharispermumsubsessile | Sampekatte |

| 16 | Blumeabelangeriana | Hulikal |

| 17 | Chrysopogonhackelii | Kodachadri |

| 18 | Cinnamomummalabatrum | Hulikal, Tenkbail,Kogar |

| 19 | Crotalaria filipes | Chakra |

| 20 | Dendrobiumbarbatulum | Kundadri, Jog, Nagavalli |

| 21 | Derris brevipes | Sampekatte |

| 22 | Desmoslawii | Hulical, Yedur, Jog |

| 23 | Diospyrossaldanhae | Nagodi |

| 24 | Ellertoniarheedii | Hulikal, Kaimara |

| 25 | Ensetesuperbum | Hulikal, Varahi |

| 26 | Eriadalzelli | Sampekatte |

| 27 | Eriocauloncuspidatum | Hosagadde |

| 28 | Eriocaulonstellulatum | Kodachadri, Hosagadde |

| 29 | Ervatamiaheyneana | Hulikal, Nagodi, Humcha |

| 30 | Erythropalumpopulifolium | Chakra, yedur, Hulical |

| 31 | Euonymus indicus | Yedur, Sampekatte |

| 32 | Eusteralistomentosa | Nittur |

| 33 | Garciniagummigutta | Kargal |

| 34 | Goniothalamuscardiopetalus | Tenkbail |

| 35 | Griffitheliahookcriana | Nagavalli |

| 36 | Gymnostachyumlatifolium | Kodachadri hills |

| 37 | Habenariaelwesii | Hosagadde |

| 38 | Habenariagrandifloriformis | Bileshvara, Sampekatte |

| 39 | Habenariaheyneana | Nittur, Chakra, Hulikal,Sampekatte, Savehaklu |

| 40 | Habenarialongicorniculata | Nagara |

| 41 | Hedyotiserecta | Sagar |

| 42 | Helixantheraintermedia | Yedur |

| 43 | Helixantherawallichiana | Jog |

| 44 | Heritierapapilio | Kodachadri |

| 45 | Holigarnaarnottiana | Hulikal, Yedur, Tagarthi |

| 46 | Holigarnaferruginea | Hulikal |

| 47 | Holigarnagrahamii | Hulikal |

| 48 | Hopeaponga | Nittur, Hulikal, Nagodi |

| 49 | Hymenodictyonobovatum | Chakra, Hulikal |

| 50 | Impatiens agumbeana | Hulical |

| 51 | Impatiens gardneriana | Hulical |

| 52 | Impatiens herbicola | Kodachadri hills |

| 53 | Impatiens kleinii | Sampekatte, Mastikatte |

| 54 | Ischaemumimpressum | Kodachadri |

| 55 | Ixorabrachiata | Hulikal, Jog, Govardhanagiri |

| 56 | Ixoramalabarica | Savehaklu, Devagaru |

| 57 | Ixorapolyantha | Hulikal |

| 58 | Jasminumcordifolium | Hulikal |

| 59 | Justiciasantapani | Hulikal |

| 60 | Justiciawynaadensis | Nagavalli |

| 61 | Knemaattenuata | Nittur,Yedur, Nagodi |

| 62 | Lagerstroemia microcarpa | Sampekatte, Yedur, Kattinkere |

| 63 | Litseacoriacea | Hulikal, Yedur |

| 64 | Mallotusstenanthus | Kodachadri, Kattinkere |

| 65 | Medinillabeddomei | Kodachadri |

| 66 | Memecylonterminale | Hulikal |

| 67 | Metereomyrtuswynaadensis | Nittur, Chakra, Hulikal |

| 68 | Moullavaspicata | Chakra, Sampekatte |

| 69 | Mussaendalaxa | Mastikatte, Yedur, Nagara fort |

| 70 | Myristicamalabarica | Hosur |

| 71 | Nilgirianthusbarbatus | Hulikal |

| 72 | Nilgirianthusheyneanuss | Sampekatte, Chakra, Yedur, Kodachadri, Nagavalli |

| 73 | Oberoniachandrasekharanii | Nagodi |

| 74 | Pittosporumdasycaulon | Yedur, Hulical, Kargal, Sampekatte |

| 75 | Plectranthusstocksii | Chakra, Kodachadri |

| 76 | Poeciloneuronindicum | Hulical |

| 77 | Polyzygoustuberosus | Hebbigere |

| 78 | Porpaxjerdoniana | Sampekatte |

| 79 | Pouzolziawighti | Nagara fort |

| 80 | Psychotriacanarensis | Yedur |

| 81 | Ramphicaralongiflora | Nagara, Hulikal, Chakra |

| 82 | Reidiamacrocalyx | Kundadri |

| 83 | Reissantiagrahamii | Hulikal |

| 84 | Rubusfockei | Nagodi |

| 85 | Salaciamacrosperma | Hulikal |

| 86 | Scutellariacolebrookiana | Gajnur |

| 87 | Seshagiriasahyadrica | Nagara |

| 88 | Smithiasetulosa | Kodachadri hills |

| 89 | Smytheabombaiensis | Hulikal, Jog |

| 90 | Strychnosdalzelli | Yedur, Hosagadde |

| 91 | Swertiacorymbosa | Nittur, Savehaklu |

| 92 | Tetrastigmagamblei | Hulikal |

| 93 | Thelepapaleixiocephala | Nagavalli forest area |

| 94 | Thotteasiliquosa | Hulikal, Nagavalli |

| 95 | Tolypanthuslagenifer | Kargal |

| 96 | Trewiapolycarpa | Nagodi, Hulikal |

| 97 | Triasstocksii | Bileshvara |

| 98 | Turpiniamalabarica | Hulikal, Yedur |

| 99 | Vateriaindica | Kodachadri |

| 100 | Vernoniaornata | Agumbe, Kodachadri |

| 101 | Zingiberneesanum | Hulikal, Savehaklu, Kargal |

PRESENT STATUS OF FOREST MANAGEMENT IN SHIMOGA

The administration of the Forest Department in the district is under the charge of the Conservator of Forests, Shimoga Circle, Shimoga. The district is divided into three Forest Divisions, namely, Shimoga, Bhadravati and Sagar Divisions, each headed by a Divisional Forest Officer. There are thirty-three forest ranges corresponding to the nine revenue taluks of the district. Each forest range is placed under the charge of a Range Forest Officer. The ranges are further divided into sections, and each section is under the charge of a Forester. Further, each section is sub-divided into beats, and each beat is under the charge of a Forest Guard who is assisted by a Watcher. Thus, there are thirty-three Range Forest Officers (in the district under the administrative control of the three Divisional Forest Officers). They are assisted by 12 Assistant Conservator of Forests inall the three Forest Divisions (Annual report, Shimoga circle 2012).

FOREST CHANGE DYNAMICS IN SHIMOGA

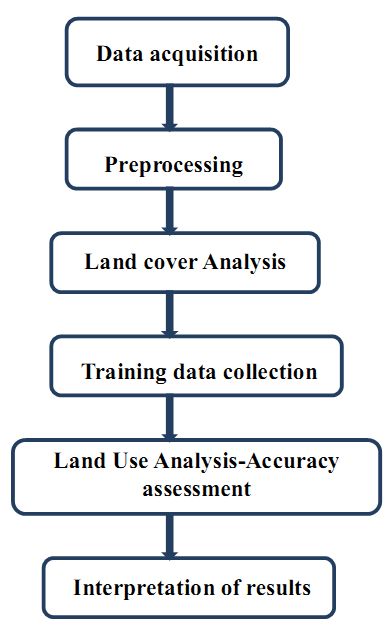

The forest change dynamics was analyzed using temporal remote sensing data of the period 1973 to 2012. The analysis involved following steps:

Figure1: steps involved in Land use land cover Analysis

Data: The spatial data acquired from Landsat Series Multispectral sensor (57.5m) and thematic mapper (28.5m) IRS LISS III sensors for the period 1979 to 2010 were downloaded from public domain as indicated in Table 1. Survey of India (SOI) topographic maps of 1:50000 and 1:250000 scales were used to generate base layers of city boundary, etc.

Table 1: Data used in the Analysis

| DATA | Year | Purpose |

| Landsat Series Multispectral sensor(57.5m) | 1973 | Land cover, Land use analysis and Fragmentation analysis |

| Landsat Series Thematic mapper (28.5m) | 1990 | Land cover, Land use analysis and Fragmentation analysis |

| IRS LISS III | 2001, 2010 | Land cover, Land use analysis and Fragmentation analysis |

| Survey of India (SOI) toposheets of 1:50000 and 1:250000 scales | To Generate boundary and Base layer maps. | |

| Field visit data –captured using GPS | For geo-correcting and generating validation dataset | |

| Google earth and Bhuvan | For digitizing various attribute data and as validation input |

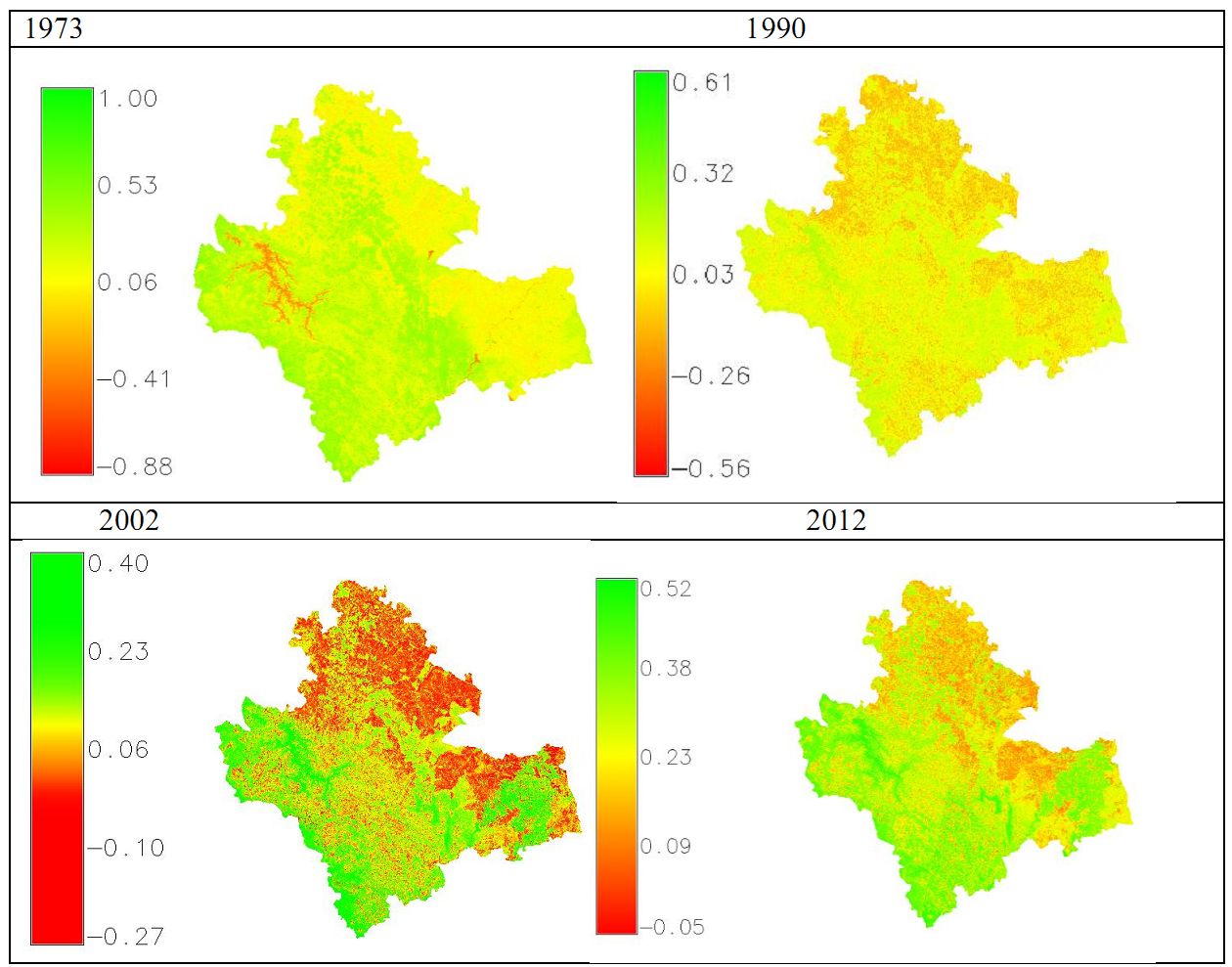

Land cover analysis: Land cover analysis through NDVI shows the percentage of area under vegetation and non-vegetation. NDVI is based on the principle of spectral difference based on strong vegetation absorbance in the red and strong reflectance in the near-infrared part of the spectrum. Figure 2 and Table 2 illustrates the spatio-temporal changes in the land cover of the region, which highlight the decline of vegetation cover from 96.57 (1973) to 91.72%.

Table 2: Extent of vegetation cover during 1973, 1990, 2002 and 2012

| Land Cover (%) | ||

| Vegetation | Non-Vegetation | |

| 1973 | 96.57 | 3.43 |

| 1990 | 96.43 | 3.57 |

| 2002 | 93.84 | 6.16 |

| 2012 | 91.72 | 8.28 |

Figure 2: Vegetation dynamics in Shimoga

Land use analysis:

Land use analysis involved i) generation of False Colour Composite (FCC) of remote sensing data (bands – green, red and NIR). This helped in locating heterogeneous patches in the landscape ii) selection of training polygons (these correspond to heterogeneous patches in FCC) covering 15% of the study area and uniformly distributed over the entire study area, iii) loading these training polygons co-ordinates into pre-calibrated GPS, iv) collection of the corresponding attribute data (land use types) for these polygons from the field. GPS helped in locating respective training polygons in the field, v) supplementing this information with Google Earth, vi) 60% of the training data has been used for classification, while the balance is used for validation or accuracy assessment.

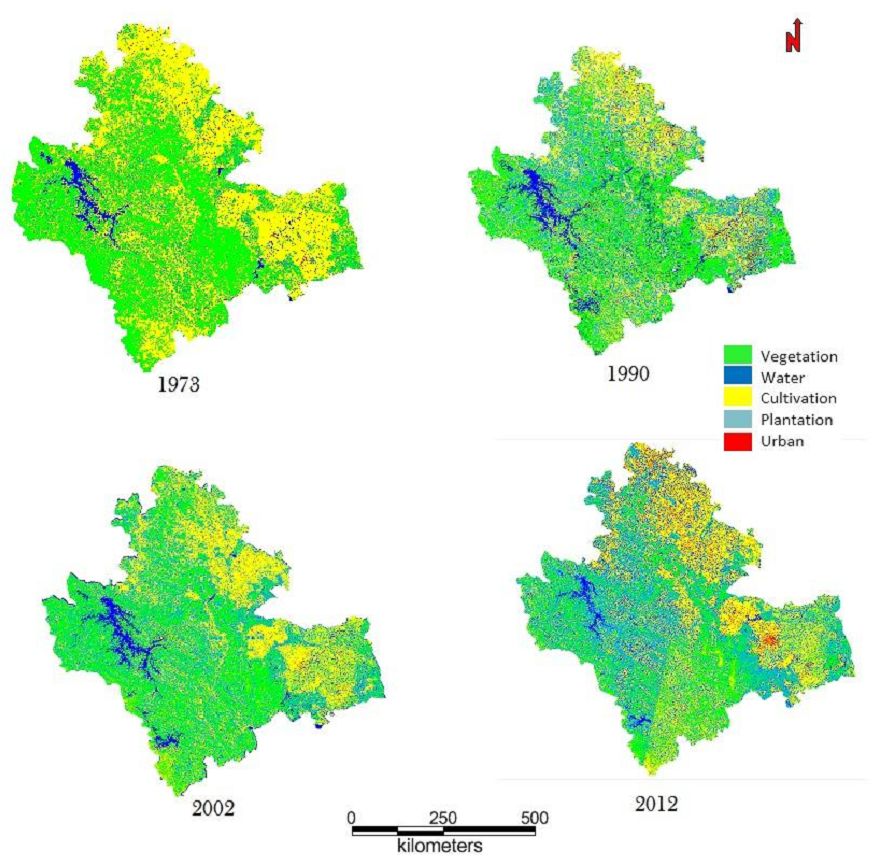

Land use analysis was carried out using supervised pattern classifier - Gaussian maximum likelihood algorithm. Figure 3 highlight changes in land uses at landscape level during 1973 to 2012. Table 3 illustrates the changes in land uses: built-up increased from 0.63% (1973) to 2.32% (2012) and forest vegetation decreased from 43.83% (1973) to 22.33% (2012). The results highlight conversion of forests to agricultures, industrial and cascaded developmental activities acted as major driving forces of degradation.

Figure 3: Land use changes during 1973 to 2012 in Shimoga district

Table 3: Land use statistics

| Land use categories (%) | |||||

| Years | Urban | Vegetation | Water | Cultivation and open area | Plantation |

| 1973 | 0.63 | 43.83 | 1.91 | 44.14 | 9.46 |

| 1990 | 0.74 | 39.90 | 4.53 | 29.68 | 25.15 |

| 2002 | 1.08 | 37.78 | 4.57 | 30.21 | 26.36 |

| 2012 | 2.32 | 22.33 | 6.09 | 34.56 | 34.69 |

KAN SACRED FORESTS OF SHIMOGA

Protection of forest patches as sacred is being practiced in many parts of India. These sacred forests are known by various names in peninsular India: such as devarakadu, devarbana or kan in Karnataka, kavu in Kerala, kovilkadu in Tamil Nadu and devrai in Maharashtra. Trees were normally not cut in such forests as they were dedicated to gods. Such sacred groves persist in many parts of Asia and Africa (Gadgil and Vartak, 1976). The forested districts of Uttara Kannada and Shimoga in the central Western Ghats of Karnataka are dotted with several groves with lofty lush-green forest cover known as ‘kaans’; literally meaning “thick evergreen forests” (Joshi & Gadgil 1991). These forest patches are also called ‘devarkaans’ (sacred forests), as the natives of these regions preserve kaan forests traditionally as the abodes of sylvan deities maintaining a lasting relationship with nature (Gokhale 2004). These Sacred forests served many functions like conservation of biodiversity and watershed, moderation of climate, and enhancement of landscape heterogeneity, which promoted varied wildlife. Studies highlight that, groves support a good number of rare and endemic species, which are extra-sensitive compared to common species, and persist only in favourable niches, and the sacred groves are ideal places for them (Jamir and Pandey 2003; Sukumaran and Raj 2007).The village sacred forests ranged in size from few hectares to few hundred hectares. The Kans of Sorabtaluk in Shimoga covered 13,000 ha or 10% of Sorab’s area. (Chandran MDS, 1997).

Management of Kans – An Historical Perspective

British government as soon as taking over the Old Mysore state surveyed the respective areas to explore the resources. In later years the government tried to make decisions relating to management of the forest area and certain years became the historical benchmarks in deciding the fate of the forests resources in the Western Ghats. Table 2 summarizes the chronological history of Kan management.

Table 2: Historical benchmarks for management of Kans in Shimoga district (Gokhale, 2004)

| Year | Event in Shimoga (old Mysore state) |

| 1801 | Mention of kans by Buchanan as forests of gods and pepper |

| 1848 | First record of Kan revenue from SorabTaluk |

| 1867 | British debated over existence of kans as separate land use pattern |

| 1868 | Brandis and Grant report on kans of Sorab |

| 1878 | Prohibition of coffee cultivation inside kans |

| 1882 | Kans converted to coffee plantations lost the status as kans in Chikmagalur (Kadur) district |

| 1885 | Kan rules were published |

| 1888 | Wingate, British forester remarks over destructive exploitation from kans |

| 1895 | Amendment in kan rule-1 |

| 1919 | M S N Rao, forester comments over the drying of streams due to felling in Shimogakans as ‘disastrous’ |

| 2001 | Left over kans as state forest or minor forest or reserve forest |

Status of Kans in Shimoga district:

There were 116 kans in the SorabTaluk but according to the forest department the present number of kans is 65. The total number of kans in SorabTaluk could be more than 65 as many earlier kans are now have the status of minor forest or district forest and are not necessarily reserved forests as considered by many forest officials.

Recognized regime by the forest department until 1960: The Shimoga circle of the Karnataka state forest department administered kans under a separate management regime till 1960, until the last reorganization of the forests in the circle. There were official prescriptions followed for the maintenance of the kans since the time of the Old Mysore state under the management of British government. The management of kans and sharing of benefits was vested with local landlords like the Gowdas of the village. There was a system of tax/lease (‘shisht’) to be paid by the local gowdas in whose name the kans were leased out. The state forest department continued the system until the local landlords lost their rights on kans mainly due to the land tenancy act.

In Shimoga district kans have been reported from taluks like Tirthahalli, Hosanagar, Sagar, Sorab, etc. Records available with Sagar forest division mention kans in taluks such as Sagar (82), Sorab (172) and Hosanagar (60). The monograph on Malnadkans, Soppinabetta and Kumri lands (1901) also mentions the existence of kans in Chikmagalur (erstwhile Kadur) district of Old Mysore state (Gokhale, 2004).

THREATS TO FOREST ECOSYSTEM

Governance: In Shimoga district, particularly, many kans were brought under the jurisdiction of the Revenue Department, which conveniently allotted kan lands for meeting various non-forestry purposes such as for growing coffee, expansion of cultivation, for grazing purposes and numerous others, inconsiderate and negligent of the rare species they conserved and also of their crucial hydrological importance. The Government also conceded large portions of kans on long leases to the Mysore Paper Mills for growing industrial woods like Eucalyptus and Acacia spp. after clearing the natural vegetation.

Fragmentation of vegetation: The Kan forests were praised in the past for their unique evergreen vegetation of lofty trees, rich moldy soils, fire security, as source of perennial streams and production of various products in demand for human subsistence, especially as centers of pepper production. Today a close look at the Kans on the ground or using aerial imageries, reveal a high degree of forest fragmentation. The composition of the landscape elements of the Kan does not conform to the past descriptions of such sacred forests from Central Western Ghats. It appears that many a stream originating in the Kan get dried up in the summer months resulting in abandonment of minor tanks constructed along their courses, thus obviously, with adverse consequences on farming downstream and water-flow into the River diminished. Such severe human induced changes in the evergreen forests of Western Ghats are bound to have cascading consequences on human welfare in the Deccan plains mainly because of reduced water flow in the east-flowing rivers.

Major human induced ecological changes in the Western Ghats started with the arrival of agriculture and animal husbandry. Collection of forest produce such as pepper, cardamom, ivory, honey, wax has gone on for a long time in the Western Ghats. Several industries were started in the early decades before independence, primarily to utilize the forest resources of the Western Ghats. These have included saw mills, brick and tile, paper, polyfibre, matchwood, plywood, and tanning. A few other industries have sprung up based on the mineral resources of the hills such as the steel works at Bhadravati. These created pressure on extraction of forest products. Pepper and cardamom, which are native to the evergreen forests of the Western Ghats, were also taken up as plantation crops on a more extensive scale in modern times. Many of the newer plantations were taken up by clear felling natural evergreen forests tracts which till then had predominantly tribal populations. Kans (Sacred groves) being the centres of spiritualism, culture and community get together are important places for re-emphasizing their roles in conservation of nature. Proper survey and mapping of boundaries of all kans must be done in order to protect them from encroachment and other threats. Strict actions should be taken against encroachers. Taking special care of threatened species and threatened micro-habitats within the kan forests will also help in protection. Providing good protection and adopting better management practices in moderately disturbed kaans could return the vegetation to high species richness and stocking density. It would also give a better chance of establishment to sensitive evergreen species, to endemic species, and to those in RET categories, as well as to economically important species, through natural succession.

We therefore recommend that the Government of Karnataka take immediate action to arrest the degradation of kan forests on priority basis by:

- Proper survey and mapping of boundaries of all kans;

- Assign the kan forests to the Forest Department for conservation and sustainable management;

- Constituting Village Forest Committees for facilitating joint forest management of the kan forests;

- Taking speedy action on eviction of encroachers from the kans;

- Giving proper importance to the watershed value and biodiversity of the kans;

- Taking special care of threatened species and threatened micro-habitats within the kans;

- Heritage sites status to ‘kans’ under section 37(1) of Biological Diversity Act 2002, Government of India as the study affirms that kans are the repository of biological wealth of rare kind, and the need for adoption of holistic eco-system management for conservation of particularly the rare and endemic flora of the Western Ghats. The premium should be on conservation of the remaining evergreen and semi-evergreen forests, which are vital for the water security (perenniality of streams) and food security (sustenance of biodiversity). There still exists a chance to restore the lost natural evergreen to semi-evergreen forests through appropriate conservation and management practices.

Source: http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/ETR/ETR53/index.htm

REFERENCES

- Chandran, M. D. S. (1997). On the ecological history of the Western Ghats. Current Science 73: 146-155.

- Gadgil, M., and V. D. Vartak. (1976). The sacred groves of Western Ghats in India. Economic Botany 30:152–160.

- Gokhale, Yogesh. (2004). Reviving traditional forest management in Western Ghats; study in Karnataka. Economic and Political Weekly (July 13): 3556-3559.

- Jamir SA, Pandey HN (2003) Vascular plant diversity in the sacred groves of Jaintia Hills in northeast India. Biodiversity Conservation12:1497–1510.

- Joshi, N. V. & Madhav Gadgil. (1991). on the role of refugia in promoting prudent use of biological resources. Theoretical Population Biology 40: 211-229.

- Karnataka Forest Department Annual Report for the Year 1990-2010

- Karnataka state Gazeteer department, Shimoga Gazetter-1975

- Pascal JP (1988) Wet Evergreen Forests of the Western Ghats of India: Ecology, Structure, Floristic Composition and Succession,InstitutFrancais De Pondicherry, Pondicherry, 345 pp.

- Ramaswamy, S.N., Rao.M. Radhakrishna and Govindappa. D.A. (2001). Flora of Shimoga District, Karnataka, University Printing Press, Manasagangothri.

- Rao. M. R, Ramaswamy. S.N. and Nagendran. C.R. (1993). A checklist of endemic species of the Indian region occurring in the western Ghats of Shimoga district, Karnataka, Journal of Mysore University, Vol.33, 131-137.

- Report of the Forest Administration in the Mysore state for the Years 1893-1956

- Sukumaran S, Raj ADS (2007) Rare, endemic, threatened (RET) trees and lianas in the sacred groves of Kanyakumari district. Indian Forester 133: 1254-1266.

- http://wgbis.ces.iisc.ac.in/biodiversity/pubs/ETR/ETR53/index.htm