| l |

|

Prakash N. Mesta, Setturu Bharath, Vishnu D.M., Subash Chandran M.D. and Ramachandra T.V. |

INTRODUCTION

Mangroves are a group of plants that occur in the coastal intertidal zones of tropics and the sub-tropics. The mangrove community as a whole consists of salt tolerant plants of soft and swampy mud, mostly trees and shrubs, with broad, leathery, evergreen leaves. In some trees roots from the main stem and branches grow vertically down and provide additional support like stilts in an unstable, slippery substratum. In many others roots protrude into the air like sticks, knobs or loops, or creep in serpentine manner all around the tree, exposed fully during the low tide. These roots are meant for taking in air for respiration, as the water-logged soil is deficient in oxygen. In some trees the seeds germinate while the fruits are still attached to the plant, and green seedlings of varied lengths hang from the parent plants until they achieve appropriate length, specific to the species, drop vertically down into the soft mud. Soon they develop the root system and become independent plants. This nature of certain mangroves to ‘give birth’ to live seedlings instead of shedding their fruits or seeds is known as vivipary.

Mangroves make special type of vegetation that exists at the boundary of two environments using a variety of survival and reproductive strategies. Till about 1960s, mangroves were largely viewed as “economically unproductive areas” and were therefore destroyed for reclaiming land for various economic activities. Gradually, however, the economic and ecological advantages of mangroves have become visible and their importance is appreciated. Every ecosystem supports human life by giving direct or indirect benefits and services. Mangrove areas are one among the most productive ecosystems on this planet. They serve as custodians of their juvenile stock and form most valuable biomass (Odum 1971). The term mangroves refer to an ecological group of halophytic plant species which is known as the salt tolerant forest ecosystem and provides a wide range of ecological and economic products and services, and also supports a variety of other coastal and marine ecosystems. Mangroves occupy less than 1% of the world’s surface (Saenger, 2002) and are mainly found between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn on all continents covering an estimated 75 percent of the tropical coastline worldwide.

Mangroves constitute one of the important parts of an estuarine ecosystem and in fact form an icon for the estuarine ecosystem. A layer of earth or sand, usually deposited by rivers and flood tides and shore free of strong wave and tidal action promotes extensive development of mangroves. They also require salt and brackish water. Mangroves are best developed on tropical shorelines where there are large areas available between high and low tide points. Large mangrove formations are typically found in sheltered muddy shorelines that are often associated with the formation of deltas at the mouth of a riverine system. Mangroves can also be found growing on sandy and rocky shores, coral reefs and oceanic islands. There are instances where islands can be completely covered by mangroves. It is impossible to describe a typical mangrove, as the variation in height and girth, even for the same species, is immense, depending on the many factors that control growth.

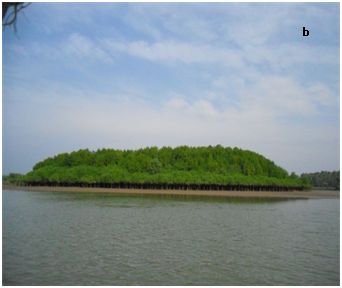

Figure 1: (a) A natural mangrove formation and; (b) a mangrove plantation in Aghanashini estuary

IMPORTANCE OF MANGROVES

A rich biodiversity is observed in the mangroves with plants and animals, which are irreplaceable, and form a good genetic treasure house. Mangrove wetlands are a multiple use ecosystem that provides protective, productive and economic benefits to coastal communities. Mangroves contribute to the stabilization of the shoreline and prevention of shore erosion. They serve as a barrier against storms so as to lessen damage to coastal land and residents. The dense network of supporting roots and breathing roots give mechanical support to the tree and trap the sediments. Without mangroves, all silt will be carried into the sea, where turbid water might cause corals to die. Mangrove trees act as sinks, which concentrate pollutants such as sewage, toxic minerals, pesticide, herbicides, etc.

The mangrove ecosystems are associated with rich diversity of organisms and are also the nursery and breeding ground of several marine fauna like prawns, crabs, fishes and molluscs. They enhance the fishery production of nearby coastal waters by storing nutrients and detritus. Through shedding of their leaves mangroves tend to remove salt accumulated in them. However, most land plants, except the halophytes, are incapable of such tolerance to salty environments. The shed leaves of mangroves turn into detritus, which is colonized by fungi and bacteria and this detritus turn into a valuable pool of nutrients. This detritus is consumed by variety of bivalves, shrimps and fishes, many of which migrate into the mangrove areas for better feeding and protection. Birds are a prominent part of most mangrove forests and they are often present in large numbers. Almost 120 birds are found in the Aghanashini estuary of Kumta taluk in the Honavar Forest Division. They use mangrove environs as breeding and feeding grounds. The Royal Bengal Tiger is one of the unique resident species of mangroves of the Sunderbans. Mangroves sustain the ecological security of the coastal areas as well as livelihood security of the thousands of fishing people of estuarine and coastal villages. Nevertheless, because mangroves grow where nothing else grows, they are always useful, even where they cannot be managed as productive forests. The enrichment of brackish and coastal waters provided by the mangrove vegetation may be substantial and should not be overlooked.

Good mangrove vegetation is an excellent indicator of the health of coastal ecosystems. Mangrove ecosystem traps and cycles various organic materials, chemical elements and important nutrients. The roots provide attachment surfaces for many organisms. Many of these attached animals filter water through their bodies and, in turn, trap and cycle nutrients. Mangroves provide protected nursery areas for fishes, prawns, crabs and shellfish. They provide food for multitudes of marine and estuarine animals, such as various fishes and prawns of diverse species, oysters etc. Many animals find shelter amidst the network of roots, where fisherman cannot cast his nest nor the boatman ferry through it. The general importance of mangroves at many levels is provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Some important uses of Mangroves

| Ecological uses | Economical uses | Social uses |

| Erosion control | Fishing | Education |

| Protection from damage | Shrimp and crab industries | Ecotourism |

| Indicator of climate change | Charcoal production | Food |

| Habitat provision | Timber production | Local employment |

| Water quality management | Firewood | Agriculture |

| Carbon Sequestration | Traditional medicine |

-

Mangroves for food security: Many nurture the misconception that mangroves are dreaded and disease causing impenetrable swamps and they need to be cleared and reclaimed for the sake of public health. In fact the value of mangroves as storehouses of food, directly in the form of edible mangrove products and honey and indirectly in the form of enhanced fishery resources, is more known to the inhabitants of estuarine villages. Today, there is rising global awareness on the importance of mangroves. Crabs, clams, oysters, fish and other food are often collected there. Mangrove trees grow well in their special conditions, and, like the tropical forest, produce a lot of leaves and other organic matter. The leaves fall in the water, where they disintegrate due to fungal and microbial action. This detritus becomes food for shrimps, crabs, oysters, shellfishes and so on, which are of immense importance in human subsistence and commerce. An entire detritus based food web of the coastal wetlands is mainly based on mangroves. This rich food is not only eaten in the mangrove swamp, but much of it may be carried out into the lagoon or to coral reefs and other coastal fisheries areas, where it helps to feed the fish. The mangroves are also used as food or as part of the food by the human beings in many places. Tender leaves of Acacia farnesiana are used as substitute for tamarind in chutneys. Tender leaves of Acrostichum aureum: Young fronds cooked and eaten (Wealth of India, vol. I., 1985). Bruguiera gymnorrhiza: Fruits edible (Kothari and Rao, 2002). Canavelia spp.: Tender pods of this leguminous climber used as vegetable. Salvadora persica: tender leaves and shoots as salad; fermented drink made from fruits (Hajra and Sanjappa, 1996). Sonneratia caseolaris: Fruits edible, eaten raw or cooked; fruit juice as a substitute for vinegar and as a condiment; tender leaves dressed with fish (Hajra and Sanjappa, 1996).

-

Mangroves for coastal protection: For thousands of years mangrove forests have provided natural buffer against cyclones and other storms that often hit the shores of southern India. The role of mangroves in protection of the life and property along the coast is being strongly realized today after the 1999 super cyclone of Orissa and the tsunami of 2004. In October 1999, a super cyclone, with wind speed of 160 miles per hour struck Orissa and killed at least 10,000 people and rendered homeless 7.5 million. However, those human settlements located behind the mangrove swamps suffered little loss. The villages in and around Bhitarkanika were spared much of the cyclone’s fury because of the vast mangrove forest. Bhitarkanika is the second largest mangrove formation in India, next only to the Sunderbans (Venkataraman, 2004). That mangrove forests protect uplands from stormy winds, waves and floods had been well known in the past. The amount of protection afforded depends upon the width of the forest. Whereas very narrow fringe of mangroves offers only limited protection, a wider belt of mangroves, with their entanglement of aerial roots, can considerably reduce wave and flood damage to landward areas by absorbing the overflowing water. Mangroves can help prevent erosion by stabilizing shorelines with their specialized root systems. This fact has been known to the traditional gazni farmers of Aghanashini, Karnataka. Before the permanent stone bunds were built by the State Government, the farmers used to prepare earthen bunds and fortify them on the tidal side by planting of mangroves.

-

Mangroves for medicines: The mangrove and mangrove associate plants have also been investigated upon for their medicinal values. The people of Kutch and Saurashtra use the smoked dry leaves of commonly occurring mangrove tree species – Avicennia officinalis for relief from Asthma (Banerjee et al. 1989). The leaves and bark of Acanthus ilicifolius, a shrubby plant associated with mangrove community, is found to be useful in nervous disorders (Banerjee et al., 1989; Kothari and Rao, 2002) whereas, the decoction of the plant with sugar candy and cumin is used in indigestion and acidity and also for promoting urine and as a cure for dropsy and bilious swellings (Wealth of India, vol. I., 1985The rhizome paste of Acrostichum aureum, a mangrove fern species, is found to be useful in the case of boils (Naskar and Mandal, 1999). An important mangrove associate tree species – Calophyllum inophyllum, has also many medicinal applications. The paste of its seeds are applied for relief from painful joints; the oil is applied in case of rheumatism, gout, scabies and other skin diseases; camphor mixed oil is used for application on ringworms and the soap from oil has strong bactericidal and fungicidal properties (Wealth of India, vol. I., 1985…). The fruits of mangrove tree - Sonneretia caseolaris are used in preparation of poultice for sprains and swellings (Hajra and Sanjappa, 1996).

-

Miscellanous uses: The bark of Avicennia officinalis yields a natural dye (Banerjee et al. 1989) while the leaves of Clerodendron inerme, a mangrove associated shrub, yield a brown dye (Kothari and Rao, 2002). The flowers of Aegiceras corniculatum are good sources of high quality white honey (Banerjee et al. 1989). The leaves of Avicennia officinalis are rich in proteins and carbohydrates and hence, used as fodder and the plants of Acanthus ilicifolius are cut before flowering, spines removed and also used for fodder (Wealth of India, vol. I., 1985The wood of mangrove plants like Avicennia officinalis and Bruguiera gymnorrhiza is a durable timber and used for construction purposes.

DISTRIBUTION OF MANGROVES

Mangroves dominate approximately 75% of the world’s tropical coastline between 250N and 250S latitude. This restricted distribution of mangroves is mainly due to the sensitivity of the species to frost and cold temperature. The most northerly sites of the mangrove distribution are the top of the Red Sea in the Gulf of Aquba (300N) and South Japan (320N); while the most southerly sites for mangrove distribution are Australia (380S) and Chathan island east of New Zealand (440S) (Walter, 1977). The total mangrove cover of the world is about 1, 81, 000 sq.kms. Over the period, there is significant decrease of mangrove cover in many countries due to various manmade changes and natural consequences. The highest concentration of mangrove species is, however found in the Indo-Malaysian region. Table 2 gives the details of mangrove covered area in various parts of the world. Mangroves of the World have been divided into two groups: Eastern group i.e. East Africa, India, Southeast Asia, Australia and the Western Pacific and Western group comprises of West Africa, South and North America and the Carribean Countries. Out of the ninety mangrove species of the world, 63 occur in Indian Ocean & West-Pacific regions while only 16 species are recorded in the Pacific-America, 16 species in Atlantic-America and 11 species in West Africa. In the eastern group, there are in all 20 species belonging to 9 families whereas in the Western group there are only four species belonging to 3 families. The species are Rhizophora mangal, Laguncularia racemosa, Avicennia nitida & A. tomentosa (Yanney-Ewusiv, 1980). Approximately 43% of the World’s mangroves are located in just four countries- Indonesia (42,550 sq.kms), Brazil (13,400 sq.kms), Australia (11,500 sq.kms) & Nigeria (10,515 sq.kms).

Table 2: Mangrove cover in various parts of world (Source: Spalding et al. 1997)

| Region | Mangrove area(ha) | % to Global area |

| South and Southeast Asia | 75,17,300 | 41.0 |

| Australia | 18,78,900 | 10.4 |

| Americas | 49,09,600 | 27.1 |

| West Africa | 27,99,500 | 15.5 |

| East Africa and the Middle East | 10,02,400 | 5.5 |

| Total | 1,81,07,700 | 100 |

In India, the mangrove vegetation can be observed all along its 5,700 km coastline. The total area covered by mangroves has been estimated to be about 700,000 ha which amounts to about 6% of the world’s mangroves. However these fragile and sensitive trees and their ecosystem have been abused, neglected and overexploited in India and face significant threats in the form of deforestation, reclamation, pollution, etc. India’s coastline is divided into the West coast (bordering Arabian Sea) and the East coast (bordering Bay of Bengal). The west coast includes the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka and Kerala whereas the east coast includes the states of West Bengal, Orissa, Andhra Pradesh, Tamilnadu and Andaman & Nicobar Islands. The west coast is more or less steeply shelved, lacks major deltas and river estuaries and is dominated by sandy and rocky substratum. On the other hand, the east coast is shallow, largely influenced by major deltas and river estuaries and mostly dominated by the deltaic alluvium hence the extent of mangrove cover along the east coast of India is comparatively larger (90%) than the west coast (10%) (Kulkarni, 2002). Mangroves in India comprise of 69 species (excluding those of salt marshes and mangrove other associate species, under 42 genera and 27 families. Of these, 63 species (41 genera under 27 families) are present on the East coast; 37 species (25 genera under 16 families) on the West coast; and 44 species (28 genera under 20 families) on the Bay Islands. The East coast has 91% of mangrove species and the West coast has 53%. The most dominant mangrove species found along the east and west coast of India are Rhizophora mucronata , R. apiculata, Bruguiera gymnorrhiza , B. parviflora,, Sonneratia alba, S. caseolaris, Cariops tagal, Heretiera littoralis , Xylocarpus granatum, X. molluscensis, Avicennia officinalis, A. marina, Excoecaria agallocha, Lumnitzera racemosa (Kathiresan, 2003). The National Remote Sensing Agency (NRSA) recorded a decline of 7,000 ha of mangroves in India within the six-year period from 1975 to 1981. In Andaman and Nicobar Islands about 22,400 ha of mangroves were lost between 1987 and 1997. In Karnataka the mangrove area has declined from 6000 ha in 1987 to mere 300 ha (Table 3).

Table 3: State wise mangrove cover (in sq.km.)

| Sr. No. | States/Union Territory | Estimated by Forest Survey of India | Estimated by States | SAC, Ahmedabad | |||||||

| 1987 | 1989 | 1991 | 1993 | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 1987 | 1992 | ||

| 1 | Andaman & Nicobar | 686 | 973 | 971 | 966 | 966 | 966 | 966 | 789 | 1190 | 771 |

| 2 | Andhra Pradesh | 495 | 405 | 399 | 378 | 383 | 383 | 397 | 333 | 200 | 372 |

| 3 | Goa | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 200 | 6 |

| 4 | Gujarat | 427 | 412 | 397 | 419 | 689 | 901 | 1031 | 911 | 260 | 991 |

| 5 | Karnataka | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 60 | 127 |

| 6 | Maharashtra | 140 | 114 | 113 | 155 | 155 | 124 | 108 | 118 | 330 | 0 |

| 7 | Orissa | 199 | 192 | 195 | 195 | 195 | 211 | 215 | 219 | 150 | 187 |

| 8 | Tamil Nadu | 23 | 47 | 47 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 23 | 150 | 30 |

| 9 | West Bengal | 2076 | 2109 | 2119 | 2119 | 2119 | 2123 | 2125 | 2081 | 4200 | 1619 |

| Total | 4046 | 4255 | 4244 | 4256 | 4533 | 4737 | 4871 | 4481 | 6740 | 4123 | |

The state of Karnataka in south India forms one of the important coastal states on the west coast. The state has a coastline of about 320 kms and has ten main rivers and few small ones draining into the Arabian Sea. They have a few luxuriant mangrove patches, most of which are of fringing type along the banks of rivers and backwaters in their estuarine regions. As per an estimate carried out, Karnataka has about 50 sq.kms. of mangrove cover which includes 14 species of mangrove plants belonging to 9 genera and 7 families (Untawale and Wafar, 1986). The coastal Karnataka comprises of three districts namely – Uttara Kannada, Udupi and Dakshina Kannada. The Dakshina Kannada and Udupi seaboard lies between 12°27’ and 13°58’ north latitude and 74°35’ and 75°49’ east longitude. It is about 177 kilometer in lengths, about 80 kilometers at its widest part. From north to south, it is a narrow strip of territory and from east to west it is a broken low plateau, which spreads from the Western Ghats to the Arabian Sea. The major part of its length lies along the seaboard. The area is intersected by many coast parallel rivers and streams and presents varied and most picturesque scenery. The length of the coastline is almost straight, but broken at places with numerous splits by rivers, rivulets, creeks and sandy ridges and bays.