People's Biodiversity Register |

|||

Prof. Madhav Gadgil, Yogesh Gokhale, P.R. Seshagiri Rao

|

|||

Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc, Bangalore-12 |

|||

| Introduction |

The best way of making people aware of science is to get them to practice it. An excellent opportunity of taking the practice of science right down to the grass-roots has recently opened up with the passage of the Biological Diversity Act. This Act provides for the establishment of Biodiversity Management Committees in all local bodies, whether Panchayats or Municipalities throughout the country. It stipulates that “the main function of the BMC is to prepare People's Biodiversity Register in consultation with local people. The Register shall contain comprehensive information on availability and knowledge of local biological resources, their medicinal or any other use or any other traditional knowledge associated with them.” Preparation of “People's Biodiversity Registers (PBR)” will be a rather unusual scientific activity. But it will be an activity that is very much appropriate to our biodiversity rich country, and very much timely in the current era of rapid technological developments.

We live in exciting times, with technological developments transforming the world around us as never before. Communication has become easy; information in large measures is becoming readily accessible. Indians are taking good advantage of many of these developments, and have become significant actors in the field of information technology. Yet Indian language applications are lagging far behind and most Indians are yet to taste the fruits of the information revolution. Over the last half-century we have acquired an in-depth understanding of life processes. This is permitting us to design novel life forms, injecting bacterial genes into cotton plants, or getting goats to produce milk containing molecules of spider silk. India, too, is part of this revolution and, Biotechnology is beginning to pick up in our country.

Yet, in the midst of all these developments, we remain a biomass-based civilization. Many Indians continue to lead lives as ecosystem people, tied closely to the resources of their environment to fulfill many of their requirements. They cultivate a wide range of plant species and varieties, consume wild fruit and fish, use fuel-wood to cook their meals and grass to thatch their huts and cowsheds, extensively employ herbal remedies and worship peepal trees and hanuman langurs. We are also a nation rich in knowledge of uses of our living resources, ranging from the classical traditions of Ayurveda, Siddha and Yunani, to folk medicinal practices and uses of vegetable perfumes, cosmetics and dyes. But our country's ecological resource base is under threat, with extensive destruction of natural habitats, widespread degradation of agro-ecosystems and a growing burden of air and water pollution. Simultaneously, India's knowledge base of uses of biodiversity is also being eroded, with the younger generation becoming increasingly alienated from the natural world.

It is abundantly clear that enhancement in the quality of life of India's ecosystem people has not kept pace with that of urban middle class, the so-called “shining India”. To overcome these imbalances we need to enhance the productivity and profitability, quality and sustainability, of our agriculture, animal husbandry, fisheries and forestry, as also the quality and sustainability of a variety of ecosystem services such as watershed conservation. This calls for a committed scientific and technical effort, an effort in which all segments of India's population must participate actively. Finally, we need to ensure that the fruits of this progress reach all our people.

| Environmental Challenges |

This formidable challenge cannot be addressed while continuing a policy of business as usual, pursuing a centralized pattern of resource management that depends on an appropriation of community's resources and people's knowledge, on homogenization of the environmental regime, and on a control and command approach. The standard wholesale solutions currently applied over large tracts of land and waters have proved to be short-sighted and to suffer from many serious shortcomings. Thus, our intensive, chemicalized agriculture is suffering from an escalation of pest and disease outbreaks, with many of the causative organisms having acquired resistance. The efforts at eradication of malaria have similarly run into rough weather, with both the malarial parasite and the mosquito vectors having evolved resistance. Large tracts of farmlands have become unproductive because of water-logging, or developed severe micro-nutrient deficiencies. Our forest resources have been over-exploited, landing women who have the responsibility of collecting wood to fuel the hearth, as well as basket and mat weavers into deep trouble. Many medicinal plant populations too have been nearly exterminated. Thus a German firm picked up a clue from Indian systems of medicine to develop a drug to treat high blood pressure based on the alkaloid reserpine from Rauwolfia serpentina. This happened well before the Convention on Biological Diversity and there was no question of benefit sharing for the appropriation of this knowledge. Once the drug came on the market, the natural populations of Rauwolfia serpentina were rapidly decimated. Many of our marine fish stocks too have declined impoverishing country boat fishermen and depriving large numbers of people of a cheap source of protein.

| Adaptive Management |

Indeed, the emerging scientific understanding of complex systems; ecological systems being amongst the most complex of all; tells us that a centralized, inflexible approach to management of living resources cannot be expected to work. The history of the management of the great wetland of Keoladev Ghana at Bharatpur, home to numerous species of resident and migratory water birds illustrates this very well. The well-known ornithologist, Dr. Salim Ali and his co-workers have spent decades studying this ecosystem. As a result of this work, Dr Salim Ali was convinced that the ecosystem would benefit as a water bird habitat by the exclusion of buffalo grazing. This was accepted by the Government and with the constitution of a National Park in 1982 all grazing was banned. The result was a complete surprise. In the absence of buffaloes, a grass, Paspalum grew unchecked and choked the wetland, rendering it a far poorer habitat for the water birds.

Scientists therefore now advocate that ecosystem management must be flexible and always ready to make adjustments on the basis of continual monitoring of on-going changes. In contrast, the Government authorities made a rigid decision to ban all grazing and minor forest product collection from Keoladev Ghana, and having once committed themselves have felt obliged to continue the ban even though it has become clear that buffalo grazing in fact helps enhance the habitat quality for the water birds. The emerging scientific philosophy therefore is to shift from such an inflexible system involving uniform prescriptions to a regime involving systematic experimentation with more fine tuned prescriptions. Under such a regime, stoppage of grazing would have been tried out in one portion of the wetland, the effects monitored and the ban on grazing either extended or withdrawn depending on the consequences observed. This would be a flexible, knowledge based approach, a system of “adaptive management” appropriate to the new information age.

| People's Knowledge |

The practice of adaptive management calls for detailed, locality specific understanding of the ecological systems. Much of the pertinent information on the status and dynamics of the local ecosystems resides with people who still depend on it for their day-to-day sustenance, and this opens up important opportunities to involve these people in a scientific enterprise. Supplies of 700 out of 776 Indian plant species used commercially for preparation of medicines still come from natural populations. There is no proper information on their current status and possible levels of over-exploitation with either Governmental agencies or pharmaceutical industry. The only reliable information on these issues, albeit limited to their own localities, resides with local forest produce collectors who are employed by agents of pharmaceutical companies, or with folk practitioners of herbal remedies. Similarly, there is no organized information on the status of the indigenous fish fauna of our freshwaters. Yet such fish constitute an important source of protein, especially for the weaker sections of the society. Again the only source of information on this issue, albeit limited to their own localities, is with our native fisher-folk.

In fact, the Keoladev Ghana story offers an excellent example of the relevance of people's knowledge. Siberian crane is one of the flagship species for which this wetland is being managed. Yet the numbers of these migrant birds have dwindled in years following the constitution of the National Park in 1982. One of the earliest attempts at preparation of People's Biodiversity Registers during 1996-97 involved a village called Aghapur adjoining Keoladev Ghana. The residents of Aghapur suggest that the National Park regulations which prevent people from digging for roots of Khas or Vetiver grass have resulted in compacting of soil, making it harder for the Siberian Cranes to get at underground tubers and corms which are an important ingredient of their diet. Whether this is the primary cause for a decline in the visits by Siberian Cranes must, of course, be assessed carefully; nevertheless, it is certainly a plausible hypothesis that needs to be taken on board in developing a management plan for this wetland.

| Biological Diversity Act |

The newly passed Biological Diversity Act 2002 has created space for making this much needed and significant transition in management of ecosystems and practice of science. This Act is a response to the many significant concerns emanating from new developments in biotechnology and information technology, and from the ongoing erosion of biodiversity. These developments imply that all organisms, even seemingly insignificant ones like microbes and worms, from the land, and in the waters, are potentially resources of considerable economic value, worthy of efforts at conservation, scientific investigation, and of securing rights over the associated intellectual property. This has prompted the development of two rather conflicting international agreements, the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights provisions (TRIPS) of GATT and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). CBD has two notable provisions. One is the sovereign rights of countries of origin over their biodiversity resources, such as our Basmati rice. The other is the acceptance of the need to share benefits flowing from commercial utilization of biodiversity resources and associated knowledge with holders of traditional knowledge, as in the case of pesticidal properties of neem leaves. There is as yet no proper resolution at the international level of how these will be implemented in view of the fact that the standard Intellectual Property Rights stipulate neither any sharing of benefits for holders of knowledge in public domain, nor the sovereign rights of countries of origin over their genetic resources. The Biological Diversity Act is a part of the Indian attempt to make some progress and to put into practice these two important provisions of the CBD.

This ambitious act aims to promote conservation, sustainable use and equitable sharing of benefits of India's biodiversity resources, including habitats, cultivars, domesticated stocks and breeds of animals and micro-organisms. With this in view it provides for the establishment of a National Biodiversity Authority (NBA) , State Biodiversity Boards (SBB) and Biodiversity Management Committees (BMC) at the level of Panchayats, Municipalities and City Corporations. The Biological Diversity Act was initially designed as an umbrella act, and as a herald of a new age it would have overridden many of the older acts. As passed, however, it only has the status of a complementary act and will have to be operated side by side with a whole range of other acts, including, in particular, those pertaining to forest, wild life, panchayati raj institutions, plant varieties and farmers' rights, and patents. There are both complementarities as well as potential conflicts in the working of these various acts that need to be worked out carefully to ensure that the Biological Diversity Act can effectively address the many new and significant challenges resulting from scientific and technological developments and from the growing strength of India's Panchayati Raj institutions.

| Biodiversity Management Committes (BMC) |

The Biological Diversity Act stipulates that “Every local body shall constitute a BMC within its area for the purpose of promoting conservation, sustainable use and documentation of biological diversity including preservation of habitats, conservation of land races, folk varieties and cultivars, domesticated stocks and breeds of animals and micro-organisms and chronicling of knowledge relating to biological diversity”. While there are many significant initiatives such as Joint Forest Management and Watershed Development towards decentralization of ecosystem management, none of the institutions set up for the purpose have a statutory backing. The BMCs have the required legislative support and should therefore be in a position to strike roots more effectively.

The Biological Diversity Act specifies that “the NBA and the SBBs shall consult the BMCs while taking any decision relating to the use of biological resources and knowledge associated with such resources occurring within the territorial jurisdiction of the Biodiversity Management Committee”. The BMCs are also authorized to “levy charges by way of collection fees from any person for accessing or collecting any biological resource for commercial purposes from areas falling within its territorial jurisdiction.” The BMCs would operate a Local Biodiversity Fund: “There shall be constituted a Local Biodiversity Fund at every area notified by the State Government where any institution of self-government is functioning and there shall be credited thereto—any grants and loans made (a) under section 42; (b) by the NBA;(c) by the SBBs;(d) fees received by the BMC;(e) all sums received by the Local Biodiversity Fund from such other sources as may be decided upon by the State Government.”

| People's Biodiversity Registers |

Most significantly, BMCs would serve to take science right down to the grass-roots, since, as mentioned above, its rules stipulate that “The main function of the BMC is to prepare People's Biodiversity Register in consultation with local people. The Register shall contain comprehensive information on availability and knowledge of local biological resources, their medicinal or any other use or any other traditional knowledge associated with them.” The preparation of People's Biodiversity Registers (PBR) is thus an important element of the follow up of the Biological Diversity Act. The information put together through the PBR exercises would be a significant input to an integrated Biodiversity Information System that would have to be constituted as the knowledge base for the implementation of the Biological Diversity Act at all scales from NBA through SBBs to BMCs. The PBRs would, therefore, not be isolated efforts, but would be part of a coordinated on-going activity with regulated access to information, feeding, in part, into a country-wide, networked database, that is expected to keep growing over time.

Given the diversity of life and ecosystems, of people and economy, over our vast country in which hunting-gathering and shifting cultivation co-exist with intensive chemicalized agriculture and modern industry, PBR exercises have to be fine tuned to local conditions. In fact, to do this effectively, it may be appropriate to go down below the level of a Panchayat/ Municipality and as in the case of Village Forest Committees organize BMCs at the level of individual villages/ hamlets/ town wards and prepare PBRs at this level. Hence, PBR exercises cannot be set tasks with all details specified, but must provide for sufficient freedom to take on board local concerns and priorities.

| PBR Process |

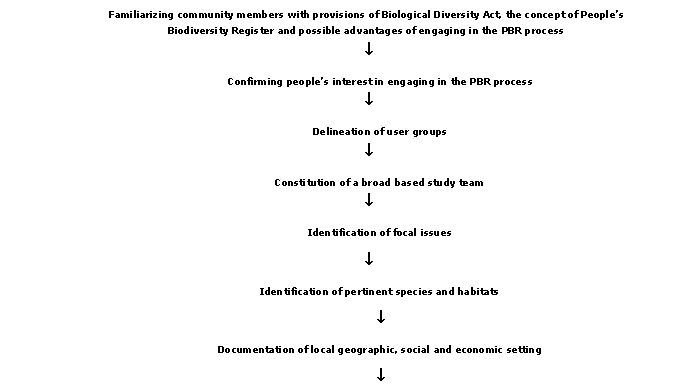

Main steps involved in the PBR process

| A co-operative enterprise |

Biodiversity is an overwhelmingly complex phenomenon. Indeed nowhere in the world has it been possible to complete an “All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory”. Hence, in interest of practicality and efficacy, PBR efforts must focus on a limited range of issues. To serve people's interests these issues must reflect their understanding of (1) what is required to support a more effective, knowledge based management of agriculture, livestock, fish, forests, water bodies and public health so as to enhance their quality of life, and (2) what kind of knowledge they possess that is significant to conserve and to add value to. Of course both these topics have to be viewed in the current context of rapidly changing conditions. While it is thus important to tailor the efforts to local conditions, much is also to be gained through a sharing of ideas, experiences and information. To facilitate such sharing, the PBR exercises need to be guided by a broad common framework with adequate flexibility to take local concerns on board.

Manifestly, local people must work side by side with experts to do justice to the task at hand. In any event, we simply do not have enough technical professionals to man such an endeavor on their own. Therefore, the specialists will need to collaborate with actors from many different segments of the society, from every village and town, from every fishing community, from every tribal hamlet, from every camp of herders. The network will have to include government officials, researchers, workers of voluntary agencies, local community leaders, as well as teachers and students from schools and colleges. Above all, it will have to bring on board “barefoot ecologists”, such as knowledgeable dispensers of herbal medicine and fishermen.

| Institutional framework |

PBR exercises would ideally be a series of nested exercises from the village/ ward to the country level supervised by the relevant management authority and implemented by an appropriate technical agency. At the state level the implementing agencies could be some scientific or educational institutions such as G.B.Pant Institute of Himalayan Environment and Development, at the district/ taluk/ city level a College or Krishi Vigyan Kendra, and at the Panchayat/ village level a High School/ youth club/ self-help group. These implementing agencies may be supported by appropriately constituted technical and civil society support groups (see Table 1).

Table 1: Institutional framework for the PBR process |

||||||

Scale ? Institution ? |

Country |

State |

District |

Taluk |

Local body |

Village / Ward |

| Supervisory Agency | NBA | SBB | ZP - BMC | TP - BMC | Panchayat/ Municipality BMC | Village or Ward BMC |

| Implementin g agency | MoEF, GoI | Nodal Agency designated By SBB | Sci/edu institution designated by ZP-BMC | Sci/edu institution designated by TP-BMC | Sci/ edu institutions & CBOs selected by BMC | Sci/ edu institutions & CBOs selected by BMVC / BMWC |

| Technical Support agencies | Technical support group (TSG) | TSG | TSG | TSG | Local sci/ edu institutions | Local sci/ edu institutions |

| Other supportive agencies | NGO consortium | NGO consortium | NGO consortium | Partners of NGO consortium | CBOs and NGOs | CBOs and NGOs |

| Initiating the process |

The very first step in the PBR process would be to communicate to people provisions of and new opportunities under the Biological Diversity Act. These would include community regulation of access to local biodiversity resources with a prospect of promoting sustainable harvests, and opportunities to generate funds through imposition of collection fees. It would also open avenues to conserve valued resources and record biodiversity related knowledge, and open up possibilities of value addition. However, it may take some time to for these promises to be translated into reality, and it would be fitting to directly address what might be gained by engaging in a PBR exercise and in developing and managing a database. It may be stressed that PBR is a document that should facilitate knowledge-based management of agriculture, livestock, fish, forests and public health so as to enhance the quality of life of the community members. The documentation should also help prevent loss of grass-roots knowledge associated with biodiversity, secure recognition for such knowledge and add value to it.

Community members and technically trained people working with them should begin the process by exploring possible uses of information generated through a PBR exercise. An indicative checklist follows:

Table 2: Possible applications of PBR information |

|

| Crop Fields and Orchards |

|

| Tree Plantations | • Forest Departments tend to develop monocultures of species of little local interest. Information may be generated to suggest alternative set of species of fodder, mulch, nectar source, bio-cosmetic, vegetable dyes or other values. • Monitor and generate good information on pollution threats such as from spraying of Endosulfon on cashew plantations. • Link appropriately with JFM programmes. |

| Trees associated with Agriculture | • Maintain, restore and add value to trees associated with Agriculture such as khejadi, neem and honge. • Plan Agro-forestry activities. |

| Animal husbandry |

|

| Forest Lands | • Promote provision of goods and services from forest lands to rural economy; encourage maintenance of watershed services, grazing resources; promote planting of trees yielding fodder, leaf manure, bamboos, other minor forest produce. • Work out methods and schedules of sustainable harvests of minor forest produce. • Promote value addition to minor forest produce. • Record and check destructive harvests by community members as well as outsiders. Many little known species such as the insectivorous plant Drosera are being collected and exported to Japan without any official agency being in the know. • Establish proper links to JFM. • Maintain proper records of people- wild life conflict to devise ways of minimizing them and obtain due compensation. • Promote traditional conservation practices like protection to sacred groves, trees and animals. |

| Grasslands | • Promote maintenance of grasslands. • Devise methods and schedules of sustainable use of grazing resources. • Promote planting of fodder trees, control of weeds on grassland. • Promote traditional conservation practices with respect to systems like Orans of Rajasthan and bugyals in Himalayas. • Record and appropriately regulate grazing pressure by outsiders and nomadic herders. |

| Hilly Lands | • Promote maintenance of natural biological communities on hill slopes. • Promote maintenance of hills supporting natural communities in urban areas for their recreational value. |

| Ponds, lakes, streams and rivers | • Promote maintenance of natural biological communities in wetlands.

|

| Seas |

|

| Sea coast |

|

| Roads | • Promote planting of a variety of indigenous tree and other plant species along roads and highways. • Organize pollution monitoring using bio-indicators such as lichens. |

| Habitation | • Promote traditional conservation practices like protection to sacred trees and animals. • Promote biodiverse natural communities in parks and open spaces around habitations. • Promote cultivation of nutritious plants such as leafy vegetables and medicinal plants in kitchen gardens. • Promote technique of terrace gardening in urban areas. |

| Institutional Lands | • Promote biodiverse natural communities and plantation of medicinal/endangered species in open spaces. |

| Industrial Establishments | • Promote biodiverse natural communities in open spaces. • Organize effective monitoring of pollution using more accessible bio-indicators such as lichens and chironomids. |

| Public health | • Monitor populations of vectors of human diseases and devise newer methods of control as the older chemical methods are proving ineffective. • Monitor microbial pollution of water sources and devise ways of provision of safer drinking water. |

| Human resources | • Promote recording of traditional knowledge as well as grass-roots innovations associated with biodiversity such as medicinal uses, vegetable dyes, cosmetics, pest control agents. This should be accompanied by appropriate measures for regulation of access to this information, protection of intellectual property rights and equitable sharing of benefits. • Promote recording of folk arts and crafts associated with biodiversity, accompanied by appropriate measures for regulation of access, protection of intellectual property rights and equitable sharing of benefits. • Involvement of students and teachers in first hand collection of information in the PBR exercises would enhance the quality of their education. • Use of modern Information and Communication Technologies in the PBR exercises would provide excellent opportunities for human resource development. |

The PBR exercise proper should be taken up only if the community members find at least some of the possibilities enumerated in Table 2 of sufficient interest to warrant their participation in the exercise.

| Involving people |

It is vital that such an exercise brings on board people linked in many different ways to the resources of their environment. To help in this endeavor the community members may be assigned to a number of User Groups. Each User Group may be viewed as comprising people with a similar relationship to their ecological resource base, differing, in some significant manner from that of members assigned to other user groups. Thus in village Masur-Lukkeri situated on an island in the estuary of Aghanashini river in Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka, [a] one group of people owns no farm land with men primarily engaged in fishing, and women in sale of these fish and collection and sale of shellfish; [b] a second group owns limited amount of hill slope land where they cultivate upland paddy, the women engage extensively in collection of shellfish and weaving mats, and both men and women engage in casual labour; [c] a third group owns estuarine farm land where they raise brackish water paddy or culture shrimp, the women weave mats and men engage in casual labour and work as masons; [d] a fourth group owns bigger chunks of plain land where they grow coconut, arecanut and pepper. While there is some correspondence between ethnic communities and user groups, our concern is with the relationship of people with natural resources and not caste or other ethnic composition. Members of different user groups may exhibit overlaps, thus women from groups [a] and [b] collect shellfish, and those from groups [b] and [c] weave mats. Members of any one group may also be linked to a variety of living resources. Thus members of group [b] are not only engaged in cultivation, shellfish collection and mat weaving but also in collection of fuel wood and leaf mulch, occasional hunting of hare and wild pigs and a variety of other activities. Besides the women in a group may differ substantially from men in their relationship to natural resources. Nevertheless, variation across the groups is much greater than within the groups, so that user groups represent a constructive way of assigning people to different categories to ensure that people with varying relationship to natural resources are represented in the PBR exercise. Of course, it would be highly desirable to involve both men and women from each group in the PBR activities.

Not all people would be equally knowledgeable, nor would they be equally interested in participating in the PBR exercise. It is also likely that some of the most knowledgeable individuals would come from the poorest households and be reluctant to speak out in a group. An important advantage of the user group approach is that these poor and socially disadvantage people would tend to be assigned to some distinctive, relatively homogenous user group where they would be better able to contribute. Therefore the identification of user groups should be followed by separate discussions, if possible separately with men and women from each user group to identify the most knowledgeable individuals- men and women from each group. As many of these as possible should then be inducted as members of the PBR study panel along with interested teachers, students, members of Community Based Organizations such as Youth Clubs or women's Self Help Groups and concerned officials such as Panchayat Secretary, Agricultural Assistant or Forest Guard.

The area within the jurisdiction of the Panchayat (or Municipality) is, of course, not immune to outside influences. A factory or town upstream may be profoundly impacting the water and fish resources of a river passing through the locality. Similarly people from neighbouring villages may be drawing on its resources for fuel wood or fodder. Or nomadic herders may annually visit the area and penning their sheep in agricultural fields supply valuable manure. The activities and interests of all these concerned external parties must be taken into account in planning for prudent management of living resources within the jurisdiction of any local body. The first task of the study team should therefore be to delineate such external user groups and identify from amongst each of them some knowledgeable individuals. It would be desirable to involve as many of these, to the extent possible, in the PBR exercise, where feasible as participants in the study team.

| Focusing the effort |

The study team should next focus on deciding the scope of the PBR exercise. As stressed above this should reflect local community's perception of what kind of information collection, to be followed by preparation and implementation of a management plan would best [a] facilitate knowledge-based management of land and water use, agriculture, livestock, fish, forests and public health so as to enhance the quality of life of the community members and [b] help prevent loss of grass-roots knowledge associated with biodiversity, secure recognition for such knowledge and add value to it. This would involve the study team revisiting the entries in Table 2, list issues of interest and then arrange them in the order of priority. A representative list of issues of interest thus identified in a few localities during the pilot phase of PBR exercise is as follows:

Table 3: A representative list of significant issues |

||

Locality |

Setting |

Significant issues |

| Bada-Yermal | A coastal fishing village in Karnataka | Impact of pollutants from petrochemical industry on marine fish stocks |

| Mala | A village on slopes of Western Ghats in Karnataka | Impact of dynamiting, especially by outsiders, on freshwater fish stocks |

| Channa- Keshavapura | A farming village in semi-arid tracts of Karnataka | Impact of pests and diseases on groundnut production |

| Mendha-Lekha | A tribal village in eastern Maharashtra | Impact of harvesting practices on tendu leaf and fruit production |

| Pardhi tanda | A village of semi-nomadic hunters-traders in eastern Maharashtra | Relative impacts of pesticide usage and hunting on quail and partridge populations |

| Telegram | A village dependent on paddy cultivation and aquaculture in Gangetic plains of West Bengal | Impact of pesticide usage on rearing of domestic ducks |

This list of focal issues should form the basis of the next phase of the PBR exercise. It should be stressed that PBR exercises are expected to be a continuing endeavor and more and more issues can be taken up for consideration as the exercises gather momentum, local capacity building takes place, a technical support network is built up and a networked Biodiversity Information System is put in place.

Thus any PBR exercise may be formulated on the basis of a list of focal issues accorded the highest level of priority by the different user groups. It would be appropriate that this list should represent significant interests of diverse user groups, rather than the concerns of only the most powerful segment of the population. The number of issues thus taken up for consideration would depend on what is practical in view of the limitations of local capacity, availability of time for the PBR activists, availability of funds and extent of external support available.

Thus for the Channakeshvapura village mentioned in Table 2 an initial short list of priority issues to be taken up in the initial phase of the PBR exercise is as follows:

Table 4: A short list of Channakeshvapura focal issues |

|

| User Group | Issues |

| Coconut orchard owners | • Control of coconut mites • Development of a live fence |

| Owners of rain-fed farms | • Control of various pests and diseases of groundnut • Control of wild pigs |

| Shepherds | • Control of various parasites and diseases of sheep • Use of traditional herbal remedies to treat sheep diseases • Management of grazing lands |

| Landless labourers | • Production of fish in irrigation tanks |

The next step is to devise a list of the various [a] species, and [b] ecological habitats that are linked to each of these themes. Table 5 provides an illustration of how such lists may be elaborated with reference to some of the focal issues mentioned in Table 4.

Table 5: Issues, habitats and species of interest |

||

Issue |

Pertinent species |

Pertinent habitats |

| Control of leaf-miner (LF) pest of groundnut | Leaf-miner, alternative host plants for LF, microbial diseases and insect parasites of LF, bird predators of LF | Groundnut farms, farms where alternative hosts of LF such as soya beans are cultivated, farm bunds and scrub savannas harbouring wild plant hosts and bird predators of LF |

| Control of wild pigs | Wild food plants of wild pigs | Farms and orchards raided by wild pigs, scrub savannas, forests |

| Use of traditional herbal remedies to treat sheep diseases | Various plant species used as herbal remedies | Farms, grasslands, scrub savannas, forests, streams, lakes |

The PBR exercise will be an innovative enterprise bringing together knowledge of the local people with scientific knowledge. For instance, preparation of the list in Table 5 would call for such inputs. The technical inputs may be derived opportunistically from a variety of sources such as Regional Stations of Agricultural Universities, Krishi Vigyan Kendras, Farm Clinics, Universities and colleges, research institutes like Central Institute of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, NGOs like the Foundation for Revitalization of Local Health Traditions and so on. However, it may take some time to acquire such inputs, and the PBR exercises may be initiated, albeit on a preliminary footing on the basis of technical knowledge accessed by local High School teachers coupled to the knowledge of local community members. Simultaneously, efforts should be organized at the state and national levels to develop [a] resource material, [b] training modules, [c] a network of experts and technical institutions to support PBR activities everywhere, and [d] a database designed to organize the locally collected PBR information and link it to a broader networked Biodiversity Information System. We will first consider the local level activities, and then the activities at state and national levels.

| The Setting |

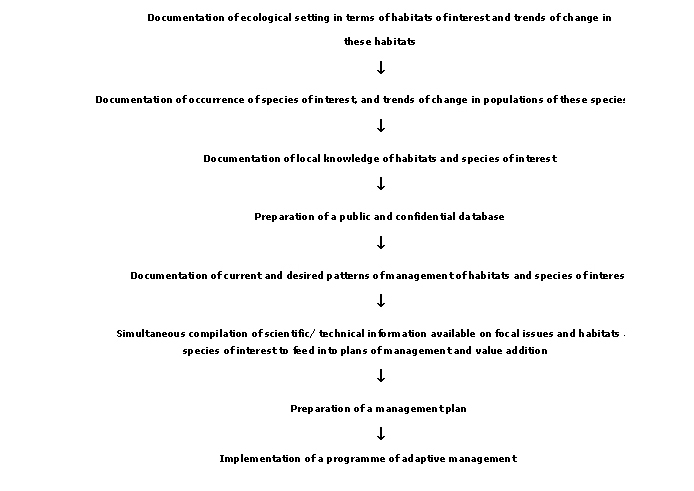

The foundation of the PBR exercise would be laid down by: {1} delineation of user groups enabling {2} the constitution of a broad based study team, followed by {3} identification of focal issues and of {4} pertinent species and {5} habitats. This will be followed by documentation of: {6} local geographic, social and economic setting, {7} ecological setting in terms of habitats of interest, and trends of change in these habitats, {8} occurrence of species of interest, and trends of change in populations of these species, {9} local knowledge of habitats and species of interest, followed by preparation of a public and confidential database, {10} current and desired patterns of management of habitats and species of interest, and, finally, {11} a management plan. Simultaneously, attempts should be made to compile scientific/ technical information available on focal issues and habitats and species of interest to feed into plans of management and value addition. Ideally, the programme of management implemented on the basis of the management plan would be an {12} adaptive management programme. The consequent developments would then be monitored and be used to revise and improve the plans of management and value addition.

Thus the next step in the process involves documentation of local geographic, social and economic setting. This must begin with the demarcation of the boundary of the area under consideration. Since the PBR exercises are meant to support the activities of Biodiversity Management Committees in local bodies, the area under the jurisdiction of a Gram Panchayat or Municipality / Corporation would be an appropriate unit for this purpose. However, such a unit may be a little too large for the purpose, and a sub-unit such as an individual village or hamlet or a ward may be appropriate. Since the purpose of the PBR is to help prepare a resource management plan, the area under consideration may also include adjacent areas under regular use, e.g. for grazing or fishing, even if they fall outside the jurisdiction of the concerned local body.

The details of the information to be collected on the geographic, social and economic setting would depend on the identified focal issues. The information may include:

• Human populations

• Livestock

• Mining and quarrying activities

• Youth and Ladies Clubs

| The Landscape |

This documentation of the geographical, social and economic setting may be followed by depiction of the setting in terms of ecosystems or ecological habitats. An ecosystem is an interacting system of all living organisms and their physico-chemical environment. This word is used in many different ways, to refer to systems on many different scales. This is because the choice of the boundary of an ecosystem is arbitrary; and one may even consider human bodies harbouring a community of viruses, bacteria, and in some cases hookworms and tapeworms, lice and ticks as an ecosystem. At the other end of the scale, the entire Western Ghats region may be referred to as a mountain ecosystem, or the entire Arabian sea coast as a coastal ecosystem. Reference may also be made to a region such as the Mandya district as an agricultural ecosystem or an agro-ecosystem, or, the Lakshadweep islands as an island ecosystem and so on. For our purpose, ecosystems are best visualized on the scale of ten to hundred square kilometers as landscapes. Such landscapes are a complex mosaic of elements of many different types. For example, in a Western Ghats tract the landscape may include elements of the following types: evergreen forest, semi-evergreen forest, humid scrub, bamboo brakes, paddy fields, rubber plantations, mixed arecanut - coconut orchards, streams, ponds, roads, habitation. In an urban area like Bangalore the landscape elements may include habitation devoid of any vegetation, habitation interspersed with trees and other plants, gardens, lakes and roads. Scattered over the landscape – and waterscape- will be several elements, or patches, of each type, mixed with those of other types. In other words, any landscape is a mosaic of landscape or waterscape elements of many different landscape or waterscape element types. Working out a system of shared conventions for classification of landscape or waterscape element types would facilitate recording, sharing and interpretation of the data. This would be a task that needs to be addressed at the national level.

Participatory mapping: Of course, people do have an intuitive mental picture of the landscape of their surroundings, including the relative extent and interrelations of the various elements in the landscape. People also have locally prevalent terms for many individual landscape elements as well as generic terms for LSE types. Thus, Janaicha (=Janai's) rahat (=sacred grove), Saheb (=Sahib's) dongar (=hill), Chavdar (=Tasty) tale (=lake). The use of such local names of landscape elements can greatly facilitate communication. Therefore, it is best to begin by preparing an inventory of the LSE/WSE types and sub-types present and a sketch map as a participatory exercise. The sketch map may depict the ecological habitats in terms of scientific categories such as degraded deciduous forest as well as locally used name of that patch of land such as kattige kadiyada betta.

Preparation of the sketch map may be followed by identification of specific elements of interest in terms of the selected focal issues. Information may then be collected, through field work as well as interviews, on the landscape/waterscape and landscape/waterscape element types as a whole, as well as those elements of special interest. Such information may pertain to, (i) current status as well as (ii) trends over time, in [a] extent, [b] occurrence of focal species, [c] goods and services or bads and disservices supplied, [d] interaction of various user groups with elements under consideration, [e] current management practices and [f] desired management practices.

| The Lifescape |

This documentation of the landscape/waterscape may be followed by that of the lifescape or incidence of the species/varieties of cultivated plants/land races of domesticated animals of interest. Discrimination amongst different forms of the great diversity of life requires that they carry distinctive names. These names have been standardized through the modern scientific system of binomial nomenclature introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1750's. But the names in popular use are not standardized in this way, so that the same name may imply very different species to different people, and the same species may be called very differently in different localities. This is true of names employed in Ayurvedic pharmacopeas as well. Thus the name Shankhapushpi (= plant with a conch-shaped flower) is applied to at least four different species: Canscora decussata (family Gentianaceae), Clitoria ternatea (family Leguminoceae), Evolvulus alsinoides (family Convolvulaceae) and Xanthium strumerium (family Asteraceae ). At the same time X. strumerium is referred to by as many as 27 different names including Arishta, Kakubha, Medhya and Vanamalini.

The names in popular usage are, of course, still of considerable significance in involving the broader masses of people in the PBR exercise. Thus, one of Karnataka's more knowledgeable barefoot ecologists is Shri Kunjeera Moolya, by occupation a landless labourer, but a highly reputed dispenser of herbal medicines from the village Mala on the slopes of Western Ghats of Karnataka. He can name about 800 different species of organisms ranging over mushrooms and plants, to ants, snakes and mammals, and can offer good estimates of the local abundances of many of these species. The experience of preparing People's Biodiversity Registers in 50 villages in seven states of India shows that most people readily know of 200-300 different species. But such folk knowledge must today be translated in terms of the more systematized, standardized scientific names. This needs to be done with great care, for in these days of commercialization of biodiversity and of patents relating to living organisms, the strength of claims critically depends on the use of scientifically valid names. For example, the Noble prize-winning biochemist, Baruch Blumberg has patented a drug against hepatitis based on information on folk uses collected from India, and many other parts of Asia and Africa. He had offered rights over this patent which pertains to molecules originally derived from Phyllanthus neruri, believed to occur in India. Further work has however revealed that there was an error and the species present in India is in actuality, not Phyllanthus neruri, but Phyllanthus amarus. An important component of technical support to be provided to local level PBR efforts will, therefore, have to relate to correct identification of focal species in terms of scientific names. Similar support will have to be provided by organizations such as the National Bureau of Plant Genetic Resources and National Bureau of Animal Genetic Resources in terms of varieties of cultivated plants and land races of domesticated animals.

In parallel with the efforts to ascertain scientific names, field work and interviews will have to be initiated to collect local level information on the focal species/varieties. This may pertain to, (i) current status as well as (ii) trends over time, in [a] abundance, [b] habitat preference, [c] occurrence in focal landscape/waterscape elements, [d] uses/disservices, [e] current management practices [f] and desired management practices.

| Knowledge |

In parallel with this documentation of habitats and species may proceed a process of documentation of people's knowledge regarding these entities, again with reference to the focal issues identified. Consider the issue of control of leaf miner, a moth whose caterpillar is a major pest of groundnut as well as soyabean and some other crops. Farmers have a number of thumb rules as to the climatic conditions under which leaf miner populations either thrive or are suppressed. There is little good scientific data on this matter, and there may be much to be gained by combining farmers' knowledge with scientific knowledge. In this case the farmers may be very happy to make their knowledge publicly available and may not wish to insist on any intellectual property rights (IPR) and maintenance of confidentiality.

Consider, as a second case, use of traditional herbal remedies to treat sheep diseases. Such knowledge may be being lost rapidly as younger people become increasingly alienated from nature and it may be very worthwhile to record it. However, there may be definite possibilities of commercial exploitation of such knowledge and the knowledge holder/s may wish to assert their IPRs and make the knowledge available only to specific parties under specified conditions. A concrete proposal to accomplish this has been developed in collaboration with the National Innovation Foundation.

| Management |

In parallel with collection of information on status and trends in focal species and habitats, information on the current patterns of their management and peoples' preferences on how these may be managed will also be generated. This would serve as the basis for the preparation of a Management Plan to support the activities of the local Biodiversity Management Committee (BMC). The plan may provide inputs on specific follow up actions to the Biological Diversity Act. Thus, it may include suggestions, with special reference to the area under the jurisdiction of the BMC, on: [a] constitution of heritage sites, for instance, in Mala people would like the area around a scenic waterfall conserved as a heritage site; [b] declaration of threatened species, for instance, in Mala, and perhaps all over Karnataka Western Ghats it might be appropriate to declare a Myristica swamp species, Myristica fatua as a threatened species; [c] ban on harvest of some species, for instance, in Mala it might be prudent to temporarily ban all harvests of highly depleted fish species belonging to genus Channa; [d] regulation of harvests of other species, for instance, in Mala, it might be prudent to strictly regulate harvests from the highly overexploited Garcinia cambogea; [d] levying of collection charges from outsiders harvesting certain species, for instance, in Mendh-Lekha the Panchayat could raise substantial funds by levying charges on collection of Tendu and Mahua; [e] regulation of outsiders engaging in recording of knowledge associated with biodiversity along with levying of some collection charges.

A variety of activities relating to decentralized planning for management of natural resources are already under way in different parts of the country. These include Watershed Development Plans as also Joint Forest Planning and Management. These activities are obviously complementary to PBR Management Plan preparation and should be properly coordinated. The main difference amongst them is that the Watershed Development and Joint Forest Management Plans pertain to one particular sector and are expected to be very detailed. The PBR Management Plans will have a broader scope and would provide a framework for more detailed plans. Such detailed plans may pertain to themes like: [a] Local breeding and release of biological control agents for control of the leaf miner pest of groundnut, [b] Implementation of total ban on dynamiting and poisoning of streams in course of fishing in streams and ponds, [c] Long term conservation of sacred groves, [d] Elimination of stagnant water pools providing habitats for mosquito breeding around habitations, and so on.

An interesting example of how such broad plans may be elaborated is provided by a school level study conducted in support of the preparation of the Karnataka Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. As a part of this effort, a team of teachers and students, led by Shri B.V. Gundappa, a Biology teacher in the local Pre-University College, made an assessment of the medicinal plant resources of Nagavalli Village Panchayat (Tumkur taluk, Tumkur district, Karnataka) on the basis of individual and group interviews. During these discussions the local people came up with the following proposals:

A. Community members are afraid that the culture and tradition of which the use of medicinal plants is an integral component may come to an end with their generation. To forestall this, they suggest that a series of steps be taken urgently:

• Create awareness regarding medicinal plants among people.

• Prepare a checklist of locally accessible medicinal plants.

• List the endangered and threatened plants amongst these.

• Enumerate the uses of different plants and how to use the plants as a medicine

• Place name boards over the trees/ plants with uses.

• Prepare information material on plants that can be grown in the kitchen gardens.

• Arrange workshops on identification, uses, and conservation of medicinal plants for the local people.

• Develop projects for storage and preservation of the seeds and other parts of the plant at one center.

• Encourage work on cultivation and hybridization of these medicinal plants.

• Develop gene banks to protect endangered plants on the brink of extinction.

• Prepare an action plan regarding cultivation of endangered and threatened medicinal plants in restricted, protected lands.

• Create a park exclusively of medicinal plants close to the village and educate people who visit that park.

• Form a local body, to act like a watchdog, to prevent smuggling, excess cutting or collection of medicinal plants.

B. Measures for Protection of Habitat of Medicinal Plants:

• Not to disturb the existing landscape.

• Protect the medicinal plants occurring now in the agricultural lands.

• Reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and manure.

• Encourage biological control measures.

C. They suggested specific roles for the following agencies:

Villagers: Try to acquire some knowledge of the medicinal plants available in their locality, and try to protect them, prevent smuggling, cutting, and destroying the medicinal plants.

Forest Department: Prevent smuggling, theft of some of the trees like sandal, teak, neem etc. Establish nurseries, distribute seedlings and plants at a low cost and encourage farmers to grow economically valuable trees like sandal, teak, mango, silver oak by giving protection to them.

Joint Village Forestry Committee: A committee involving both forest department, and village members should be formed, and it should identify empty lands near by village where nothing has been grown, and in those lands try to cultivate medicinal plants.

Agricultural department: Establish research centers, nurseries, and medicinal plant gardens where information regarding cultivation of medicinal plants will be available, and medicinal plants will be supplied at nominal cost to the people. Establish a center where people can sell their products for a reasonable price.

NGOs: Education and awareness creation regarding medicinal plants through posters, street plays, skills etc.

Agencies preparing Ayurvedic medicines : Visit the locality on fixed days and purchase the medicinal plants. Encourage people who grow medicinal plants on an extensive scale by giving some incentives, such as loan, and subsidy.

Gram Panchayat: Pass a resolution that people should take permission and clearance from Gram Panchayat when collecting medicinal plants and also when cutting trees like neem, mahua, Pongomia etc.

Taluk Panchayat : Monitor the activities of Gram Panchayat and also help out interested people in maintaining and conserving medicinal plants.

District Panchayat : Organize workshops for NGO's, Govt. officials, officers, teachers regarding the traditional uses and importance of medicinal plants and encourage them to continue those elements of the culture and tradition that are practical.

A medicinal plants conservation agency should be formed, with sub-units in schools etc. This agency should monitor village level action plans prepared by the villagers.

The ultimate objective of the PBR exercise is to put in place a pattern of development compatible with the objectives of conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and equitable sharing of benefits with the co-operation of all stakeholders. However, it is not possible to arrive at an adequate set of prescriptions for implementing these objectives as a one-time effort. Difficulties will arise while attempting to implement any set of management prescriptions; there would be unexpected consequences, new technologies will become available. It is therefore necessary to put in place a programme of monitoring based on a carefully selected set of criteria and indicators, to continue to derive lessons from these experiences and to continually update the management prescriptions. Such criteria and indicators may permit effective monitoring at the ground level of the manner in which the agreed upon management prescriptions are being implemented. Thus, if the prescriptions call for complete protection of a patch of forest, useful indicators may include: number of cut tree stems, extent of cattle dung, and number of spider webs and ant hills. The Indian Institute of Forest Management, Bhopal has good experience of developing such criteria and indicators.

To reiterate, the PBR process cannot be a one-time activity; we have to continually strive towards conserving biodiversity, using it sustainably and attempt to put in place a fair pattern of benefit sharing. This has to be an on-going process of learning while doing.

| Biodiversity Information System |

The PBR exercise will have to be an enterprise bringing together knowledge of the local people with scientific knowledge. In part, the technical inputs may be derived opportunistically from a variety of local sources such as Krishi Vigyan Kendras, Universities and colleges, research institutes and NGOs. However, simultaneously, efforts would have to be organized at the state and national levels to develop [a] resource material, [b] training modules, [c] a network of experts and technical institutions to support PBR activities everywhere, and [d] a database designed to organize the locally collected PBR information and integrate it with a broader networked Biodiversity Information System.

The PBR exercises would generate, on a continuing basis, and throughout the country, much information of value. While the individual PBR databases would remain the property of the concerned community, individual local communities as well as the society at large would benefit if these are integrated into a Biodiversity Information System that would also be linked to other scientific databases, or databases providing information on markets.

An important focus of the PBR exercise should be species of interest to people, as being of commercial, subsistence, nuisance, cultural value. One may aim at compiling a list of such significant species for all India, perhaps some 7500 species, of which any village Panchayat may harbour ~ 300. Good resource material and training programmes need to be organized to build capacity at the level of High School and College students, teachers and local knowledgeable individuals to identify these reliably. This needs to be supplemented by capacity to record ecological habitats following a common system of classification and collection of ecological data using some standardized methodologies. The data thus generated may feed into a relational database facilitating sharing and widespread use of the information.

The Biodiversity Information System could bring together locally collected as well as scientific information on these 7500 species with reference to the following topics: scientific and popular names; field identification; diagnostic characters, images, morphology, life history / phenology, ecological interactions, behaviour, habitat use, geographical distribution, abundance, trends in abundance, global uses, local uses, ecological services, conservation measures, good habitat management practices, good population management practices, good practices of handling individuals, propagation methods, environment friendly control methods, value addition technologies, marketable products and prices, literature, and experts.

The Biodiversity Information System could also compile locally collected as well as scientific information on the ecological habitats in the country with reference to the following topics: scientific and local terms; distinguishing field characteristics, images, structural properties, characteristic species present, geographical distribution, frequency of occurrence, trends in occurrence over time, goods and services / disservices, good habitat management practices, conservation measures, marketable products and prices, literature, and experts.

| Blazing new trails |

The prospect of bringing together detailed locality and time specific information on biodiversity collected from all over the country with the scientific information is an exciting one, and promises to generate new levels of understanding. Such an enterprise may even lead to new ways of doing science. This knowledge base would undoubtedly enhance our abilities to conserve, sustainably use and equitably share the benefits from our rich heritage of biodiversity resources and associated knowledge, at all levels from individual villages to districts, states and the country as a whole. At the same time this effort would have a number of significant spin-offs; serving to enhance the quality of education, helping to bridge the digital divide, and building capacity for decentralized local level planning. To make people aware of these opportunities is a fitting activity for the Year of Scientific Awareness. Of course, this can only be the first step; it must be followed by serious efforts to launch the preparation of People's Biodiversity Registers throughout the country and to create a unique blend of folk and formal science that will do credit to the genius of our country.