ABSTRACT

Biofuel is emerging as viable alternative to fossil oil resources. The suitable feedstock for biofuel production are generally rich in carbohydrate composition. Biomass rich in carbohydrate as well as renewable marine resources such as seaweeds, marine algae, which proliferates fast and occurs abundantly are utilized as a feedstock for production of ethanol following acid and enzyme hydrolysis. – Ulva lactuca, a green seaweed accumulates carbohydrate throughout its growth period and was investigated for production of ethanol using enzyme extracted from the natural marine source. Seaweed biomass estimated for the total carbohydrates, reducing sugars, cellulose, protein and lipids composition. Cellulose are converted to simpler sugars by simultaneous saccharification using chemical treatment and successive saccharification using microorganisms. Among the different microorganism investigated for efficient bioethanol production, naturally available baker’s yeast yielded around 16.69g/l of ethanol, combination of bacteria with yeast yielded around 18.09 g/l of ethanol and combination of various fungal strains and yeast yielded around 18.22- 24.98g/l of ethanol and the maximum yield of 24.98g/l with Aspergillus sp. followed by 19.55g/l with Trichoderma sp. The study reveals that fungal species are the best cellulose degrading microbes and estuarine seaweed Ulva as the best potential feedstock for bioethanol production.

INTRODUCTION

Biomass can be the best alternative source for the production of fuel and to meet the needs of the present and future generation. (Kyung A Jung et al., 2012). Fuels derived from biomass feed stocks popularly known as biofuel have been reported to be an attractive and excellent alternative to conventional petroleum derived products (PDF), as these are C neutral and renewable. (Masami et al., 2008). Bio-ethanol is used as an alternative for gasoline, and to traditional fossil fuel-derived energy sources, as these can be produced from abundant supplies of renewable biomass (Na Wei et al., 2013). Marine algal biomass is attracting worldwide interest for its potential as an environmental- friendly and economically sustainable resource. They are categorized as two types: micro algae and macro algae. Micro algal species have been used in the production of biodiesel whereas, macro-algae are being presently used in the production of bio-ethanol. Marine macro-algae are a group of large photoautotrophic multicellular, sessile, benthic plants commonly known as seaweeds and comprise of more than 25,000 species worldwide with considerable morphological and functional diversity (Holdt and Kraan 2011).

These algae are plant like organism that generally live attached to rock or other hard substratum in coastal areas. They belong to three different groups, empirically distinguished on the basis of pigment present – brown algae (phylum-Ochrophyta), red algae (phylum-Rhodophyta) and green algae (phylum-Chlorophyta). Distinguishing these three phyla, however involves more substantial difference than color. In addition to the pigmentation, they differ considerably in ultrastructure and biochemical features including photosynthetic pigments, storage compounds, composition of cell wall etc. (Holdt and Kraan 2011). Table 1 represents the seaweeds with their polysaccharides and respective monosaccharide’s.

Table 1: Carbohydrate composition of seaweeds (Percival et al., 1967)

Green-algae such as Ulva spp., Enteromorpha spp., and Caulerpa spp. consists starch, cellulose, ulvan and mannan as their structural and storage polysaccharides. Unlike the other two macro-algae species, green seaweeds have a high cellulose content in the cell wall (38-52% dry wt.) (Lahaye and Robic, 2007). Seaweed species with higher cellulose content together with higher growth rate is of great importance for sustainable bio-ethanol production (Feng et al., 2011; Kim, 2010; Suganya et al., 2013, Trivedi et al., 2013). Kim et al., (2001) reported production of 7.0 to 9.8 g/L bioethanol from raw macroalgae (Laminaria japonica) via dilute-acid pre-treatment followed by simultaneous enzymatic saccharification and fermentation with Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The low bioethanol yield obtained was because S. cerevisiae could only consume glucose but not Mannitol, which was found to be 81% of the total sugars in the hydrolysates. Yeast, under anaerobic conditions, metabolizes glucose to ethanol primarily by way of the Embden–Meyerhof pathway (EMP Pathway).

Though theoretical yield of ethanol is 51%, only 48% of ethanol is achievable as small percentage of sugars are utilized for building up of cell components in the yeast. However, their saccharification and fermentation are yet to be investigated. Thus, special efforts are required to understand these processes with a view to identify the potential of such macro algae for bioethanol production (Khambhaty et al., 2012). In a study by Schwarz (2001) and Milala et al., (2005) various microorganism were reported which are able to degrade cellulose such as Bacterias like Trichonympha, Clostridium, Actinomycetes, Bacteroides succinogenes, Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens, Ruminococcus albus, and Methanobrevibacter ruminantium. and fungal species like Chaetomium, Fusarium Myrothecium, Trichoderma, Penicillium, and Aspergillus. Hence the present study focuses on the assessment of Ulva lactuca for its credibility as a potential feedstock for bio-ethanol production.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS:

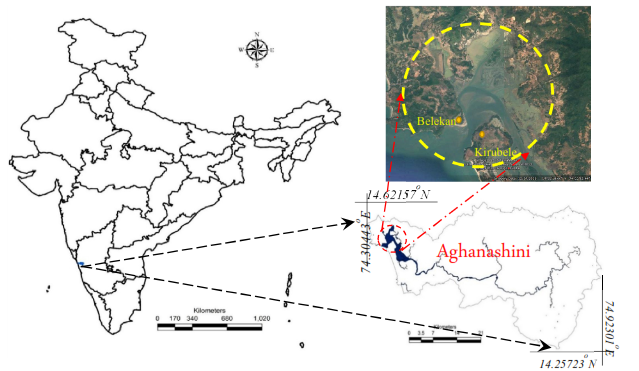

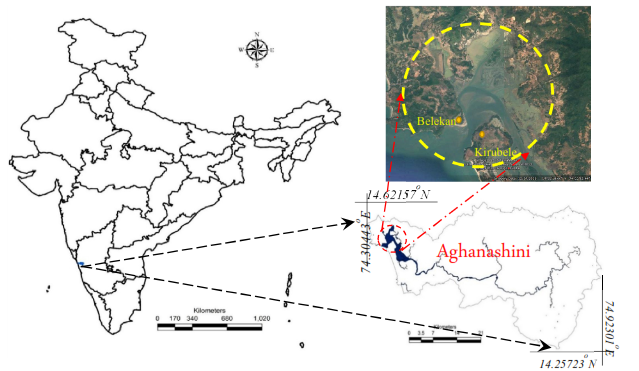

2.1. Collection of seaweed sample: The green seaweed was collected from Kirubele (Lat 14°13'47.64" N Long 74°21'30.31" E) and Belekan (14°31'4.64" N 74°20'43.68" E) river mouth station, in the estuary of Aghanashini River (Lat 14.391° to 14.585° N; Long 74.304 ° to 74.516° E) which is situated along the coast of Uttara Kannada of Karnataka, India. The seaweed samples were thoroughly washed with tap water to remove salts, epiphytes and debris and dried in shade to attain constant weight. After drying, the seaweeds samples were powdered using mortar and pestle and stored in zip-lock covers for further analysis. Samples at Kirubele region was adequate (biomass, etc.) for further analysis.

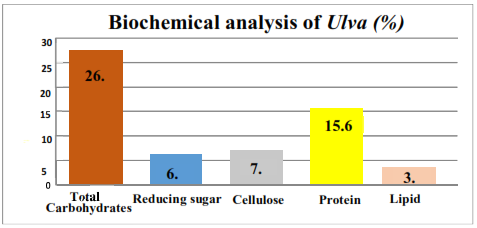

2.2. Biochemical composition of Ulva lactuca: The biochemical composition of Ulva lactuca includes total carbohydrates (DuBois et al., 1956), protein (Ohnishi et al., 1978), lipids (Folch et al. 1957), reducing sugar (Miller, 1972) and cellulose determination by the following methods respectively (Updegroff, 1969).

2.3. Successive saccharification:

2.3.1 Acid hydrolysis of algal biomass: Sample which was crushed into fine particles was subjected to acid pre-treatment (dilute 2.5N HCl). 100 mg of the sample was taken in a test tube and 5ml of the diluted acid was added and kept in boiling water bath for 3 hrs. After hydrolysis, sample was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10min and supernatant was collected and made up to 100 ml for further experiments.

2.3.2 Microorganism isolation: Bacteria was isolated from gut portion of brachyuran crabs (Grapsus albolineatus) which were also collected from the sampling locations (where seaweeds were collected) and Fungal isolates were obtained from the 2 types of soil samples – (i) soil which was used for decomposition of organic matter, (ii) normal moist soil. These microorganisms were subjected to biochemical characterizations, Congo red test. The pure cultures of microorganisms were obtained by quadrant streaking methods. Later these pure cultures were grown on the seaweed sugars which was obtained after the acid pretreatment.

2.4. Fermentation of algal hydrolysate: After the incubation time for the microorganisms the cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 3000rpm for 15min and later the samples were subjected to fermentation in an airtight container with an outlet (for the release of CO2). This process is carried out for 3 days to ensure maximum reducing sugar is converted to ethanol by yeasts.

2.5. Estimation of Ethanol: Once the fermentation is complete then the liquid was distillated at 78°C for obtaining ethanol. The percentage of ethanol was spectroscopically detected by acid potassium di-chromate method.

Fig1: Study Area

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION:

3.1. Ulva lactuca: Ulva lactuca is also known as sea lettuce. This species is tolerant to environmental parameters such as desiccation, sunlight and variations in salinity and temperature. This enables it to occupy a broad range of habitats from the upper supratidal (mainly rock pools) to the sub tidal. Hence it occurs throughout the year (Pereira and Neto, 2014). It grows up to 20 cm tall, light green to dark green in color, blades are folded and are like waxed paper to touch, reproduces both asexually and sexually. It is one of the edible seaweed in most of the South East Asian countries. (http://www.algaebase.org/).

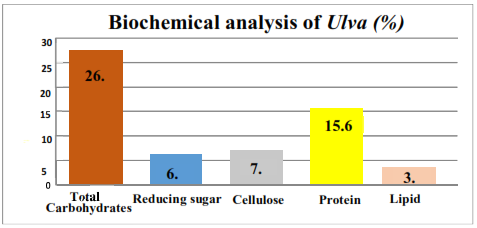

3.2. Biochemical composition of Ulva lactuca: Fig 2 represents the average composition (based on triplicate samples) of macro molecules such as total carbohydrate,

reducing sugar, cellulose, protein and lipid in Ulva lactuca.

3.3. Selection of microorganisms for successive saccharification:

3.3.1 Bacteria Isolation: Cellulose degrading bacteria was isolated using Carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC), as a sole source of carbon for their growth. The colony characterization of the cultures was performed and it was identified as gram negative cocci and gram negative bacilli.

3.3.2 Bio-chemical characterization of the bacterial isolates: Bacterial samples were isolated and subjected to bio-chemical assay and were characterized using the biochemical kit procured from Hi-Media technologies (Kit no. KB-001) for identifying the bacterial groups and strengths in various applications. Table 2 describes the biochemical characterization of the bacteria 1 and 2.

Fig 2: Biochemical composition of Ulva

Table 2: Biochemical characterization of bacteria.

Sl.no |

Bio-Chemical Tests |

Bacteria 1 |

Bacteria 2 |

1 |

Indole |

- |

- |

2 |

Methyl Red |

+ |

- |

3 |

Voges–Proskauer |

- |

- |

4 |

Citrate Utilization |

- |

+ |

|

Carbohydrate Fermentation |

|

|

5 |

Glucose utilization |

+ |

+ |

6 |

Adonitol utilization |

- |

- |

7 |

Arabinose utilization |

V |

V |

8 |

Lactose utilization |

- |

- |

9 |

Sorbitol utilization |

- |

- |

10 |

Mannitol utilization |

V |

- |

11 |

Rhammnose utilization |

- |

- |

12 |

Sucrose utilization |

+ |

+ |

*Result inference: “–“Negative test, “+” Positive test, “V” 11-89% positive test.

3.3.3 Fungi Isolation: The fungal strains were isolated from 2 types of soil samples (decomposed soil and moist soil sample) on potato dextrose agar (PDA) substituted with 1% of Carboxy methyl cellulose. After serial dilution, the colonies appeared in the following plates 10-1, 10-3 in organic decomposed soil and in 10-2 moist soil sample. The preliminary test of fungal analysis was carried out by characterizing the fungal colony obtained (listed in table 3). Later the samples were identified by wet mount method

Morphology |

Form |

Elevation |

Margin |

Color of the

colony above |

Color of the

colony behind |

Identification by wet mount |

Fungi 1 |

Irregular |

Raised |

Curled |

White to black |

Creamish to yellow |

Aspergillus |

Fungi 2 |

Circular |

Convex |

Lobate |

Green |

Brown |

Trichoderma |

Fungi 3 |

Filamentous |

Nmbonate |

Undulate |

White |

White to cream |

Rhizopus |

Fig 3: Micrographs of fungal spores. 1.Aspergillus, 2.Trichoderma, 3.Rhizopus

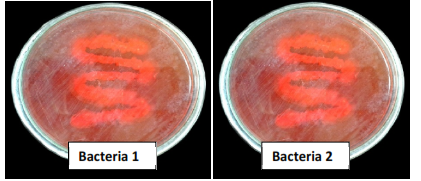

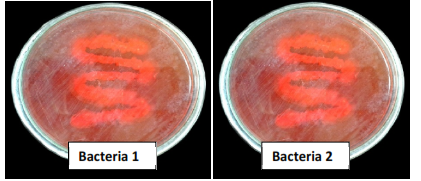

3.3.4 Congo red inhibition test: This test is performed for screening of cellulose degrading bacteria. Similar tests were reported earlier for screening bacterial isolates from gut region of the insects (Gupta et al., 2012). Fig 4 highlights inhibition regions in the Congo red fed bacterial culture plates that shows high cellulose degradation abilities.

Fig 4: Congo red inhibition test for bacterial samples.

3.4. Successive saccharification of algal biomass: Hong et al., 2014, conducted a comparative analysis of red, brown, and green seaweed’s enzymatic saccharification process where the seaweeds were pretreated with acid hydrolysis followed by commercially available enzymatic hydrolysis in order to procure maximum reducing sugar for ethanol production. Tan et al., (2014) followed SSF (Simultaneous saccharification and fermentation), which yielded twice the quantity of reducing sugar by acid hydrolyses with enzymatic saccharification. In both these studies commercially available enzymes were used which are likely to be cost inhibitive. Hence, samples after acid hydrolysis was inoculated with naturally found isolates to convert spontaneously the polysaccharide to monosaccharide.

3.5. Fermentation of algal hydrolysate: Yanagisawa (2013) used bio-engineered yeast spp., which has the ability to convert also xylose and other sugars to bio-ethanol towards maximum conversion. Compared to this, in the current experiment yeast colonies were isolated from naturally available environment and cultured on Potato dextrose agar. Fermentation was carried out for three days using the yeast spp, based on earlier report of maximum bio-ethanol yield in three days (Hong et al., 2014), and subsequent implications of acetaldehyde or acetic acid (beyond three days). The various inoculates and their incubation time and temperature is provided in table 4.

Table 4: Fermentation with various microbes (bacteria, fungi, yeast)

Substrate |

Combination of

Organisms |

Incubation time

(days) |

Temperature

(o C) |

Ulva |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

Ulva |

Bacteria 1 |

1 |

37 |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

Ulva |

Bacteria 2 |

1 |

37 |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

Ulva |

Trichoderma |

3-4 |

28-30 |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

Ulva |

Aspergillus |

3-4 |

28-30 |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

Ulva |

Rhizopus |

3-4 |

28-30 |

Yeast |

3 |

28-30 |

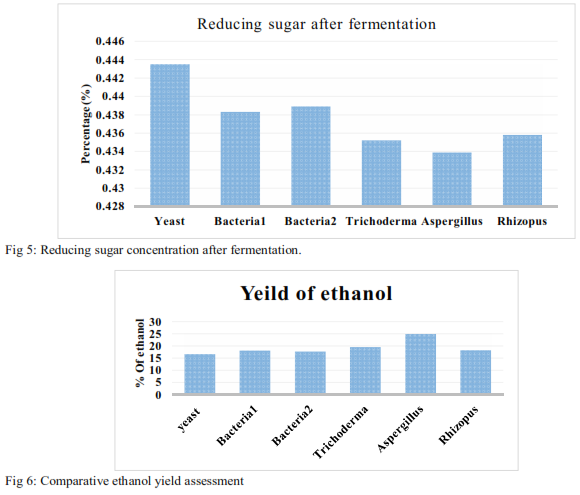

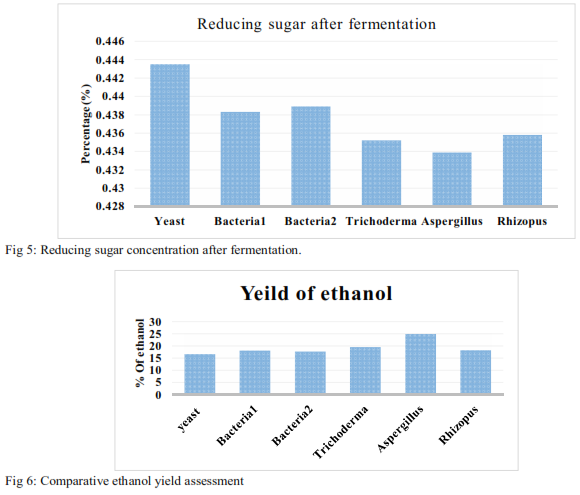

After 3 days of incubation the fermentation broth was used to estimate the reducing sugar in the broth and the results are listed in Table 5.

Table 5: Percentage of reducing sugar after fermentation.

Organism |

% of Reducing sugar |

Sugars Utilized (%) |

Yeast sp. |

0.443 |

92.72 |

Bacteria 1 |

0.438 |

92.80 |

Bacteria 2 |

0.438 |

92.80 |

Trichoderma |

0.435 |

92.85 |

Aspergillus |

0.433 |

92.88 |

Rhizopus |

0.435 |

92.85 |

The results show low percentage of RS from Aspergillus followed by Trichoderma, indicating efficient conversion of RS to bio-ethanol (Fig 5). However, yeast sp. showed a comparatively higher remnant RS compared to the fungal isolates in the liquid broth and the results are in accordance with the earlier studies of in-complete fermentation due to yeast’s inability to digest maltose. However, further analyses are required to establish competitive fermentation ability as well as to estimate the percentage conversion of ethanol from reducing sugars.

After batch-fermentation, the bio-ethanol derived was distillated at 78 °C and the distilled sample was used to estimate the concentration of ethanol.

3.6. Estimation of ethanol: The present bio-ethanol estimation (g/l) was done by standard method (Gupta et al., 2012) using K2Cr2O7 reagent. The various standards prepared at different concentrations ranging from (5-25 %). The batch fermentation studies conducted with the bacterial, fungal and yeast isolates presented in Fig 6, which showed relatively high bio-ethanol concentration in Aspergillus species and a low bio-ethanol concentration in yeast sp. The bacterial isolates showed a marginal difference in bio-ethanol concentration compared to the yeast sp. High bio-ethanol production in fungal sp. (Aspergillus followed by Trichoderma sp.) is due to the presence of abundant extra-cellular cellulolytic enzymes and abilities to degrade cellulose rapidly (Kadarmoidheen et al., 2012).

Table 6: Yield of ethanol obtained from following organisms:

Organism |

Yield of ethanol (g/L) |

Yeast |

16.69 |

Bacteria 1 |

18.09 |

Bacteria 2 |

17.71 |

Trichoderma |

19.55 |

Aspergillus |

24.98 |

Rhizopus |

18.22 |

Table 6 lists the percentage yield of bio-ethanol (g/L) using various combinatory of inoculums (as explained in the earlier table 3) during the batch fermentation process. The combination of acid hydrolyzed sample with yeast yielded 16.69 g/L of ethanol whereas with bacteria 1 and 2 yielded 18.09 g/L and 17.71 g/L of bio-ethanol respectively. Contrary to the bacterial and yeast samples, the fungal isolates Aspergillus has achieved the maximum yield of ethanol (24.98 g/L) followed by Trichoderma (19.55 g/L). Earlier studies (Yanagisawa et al., 2013) reported 40g/L of ethanol in green seaweed and 27.5 g/L of ethanol in Ulva sp. using xylose fermenting S. cerevisae and Ethanogenic E. coli for fermentation.

CONCLUSION

The current study focusses on the bioethanol prospects of estuarine macroalgae – Ulva lactuca. The biomass obtained from Kirubele of Aghanashini estuary was subjected to various biochemical study and the estimation reveals 26.71% of total carbohydrates and 6.09% of reducing sugar with cellulose of about 7.64% which is later subjected to successive saccharification by naturally obtained microorganisms and finally subjected for fermentation using Saccharomyces cerevisae (naturally available baker’s yeast). The combination of Aspergillus with dilute acid treatment yielded the maximum amount of ethanol of about 24.98g/l. Therefore, this study demonstrates the utilization of estuarine green seaweed Ulva lactuca as potential feedstock for bioethanol production.

REFERENCE

- DuBois, M., Gilles, K. A., Hamilton, J. K., Rebers, P. A. T., & Smith, F. (1956). Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical chemistry, 28, 350-356.

- Feng, D., Liu, H., Li, F., Jiang, P., & Qin, S. (2011). Optimization of dilute acid hydrolysis of Enteromorpha. Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology, 29(6), 1243.

- Folch, J., Lees, M., & Sloane-Stanley, G. H. (1957). A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J biol Chem, 226(1), 497-509.

- Gupta, P., Samant, K., & Sahu, A. (2012). Isolation of cellulose-degrading bacteria and determination of their cellulolytic potential. International Journal of Microbiology, 2012.

- Holdt, S. L., & Kraan, S. (2011). Bioactive compounds in seaweed: functional food applications and legislation. Journal of Applied Phycology, 23(3), 543-597.

- http://www.algaebase.org/

- Jang, J.-S., Cho, Y., Jeong, G.-T., Kim, S.-K., 2012. Optimization of saccharification and ethanol production by simultaneous saccharification and fermentation (SSF) from seaweed, Saccharina japonica. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 35, 11–18.

- Kadarmoidheen, M., Saranraj, P., & Stella, D. (2012). Effect of cellulolytic fungi on the degradation of cellulosic agricultural wastes. Int. J. Appl. Microbiol. Sci, 1(2), 13-23.

- Khambhaty, Y., Mody, K., Gandhi, M. R., Thampy, S., Maiti, P., Brahmbhatt, H., & Ghosh, P. K. (2012). Kappaphycus alvarezii as a source of bioethanol. Bioresource Technology, 103(1), 180-185.

- Kim, J. K. (2010). Pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of Ulva pertusa Kjellman (Doctoral dissertation, MS, Thesis. Inha University, Incheon, Korea).

- Kim, K. E., Choi, O. S., Lee, Y. J., Kim, H. S., & Bae, T. J. (2001). Processing of vinegar using the sea tangle (Laminaria japonica) extract. Korean J Life Sci, 11(3), 211-217.

- Lahaye, M., Robic, A., 2007. Structure and functional properties of ulvan, a polysaccharide from green seaweeds. Biomacromolecules 8, 1765–1774.

- Lali, A. (2016). Biofuels for India: what, when and how. Current Science, 110(4), 552-555

- Lee, J. E., Lee, S. E., Choi, W. Y., Kang, D. H., Lee, H. Y., & Jung, K. H. (2011). Bioethanol production using a yeast Pichia stipitis from the hydrolysate of Ulva pertusa Kjellman. The Korean Journal of Mycology, 39(3), 243-248.

- Masami, G. O., Usui, I., & Urano, N. (2008). Ethanol production from the water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes by yeast isolated from various hydrospheres. African journal of microbiology research, 2(5), 110-113.

- Milala, M. A., Shugaba, A., Gidado, A., Ene, A. C., & Wafar, J. A. (2005). Studies on the use of agricultural wastes for cellulase enzyme production by Aspergillus niger. Res. J. Agric. Biol. Sci, 1(4), 325-328.

- Miller, G. L. (1959). Use oi Dinitrosalicylic Acid Reagent tor Determination oi Reducing Sugar. Analytical chemistry, 31(3), 426-428.

- Mutripah, S., Meinita, M. D. N., Kang, J. Y., Jeong, G. T., Susanto, A. B., Prabowo, R. E., & Hong, Y. K. (2014). Bioethanol production from the hydrolysate of Palmaria palmata using sulfuric acid and fermentation with brewer’s yeast. Journal of applied phycology, 26(1), 687-693.

- Ohnishi, S. T., & Barr, J. K. (1978). A simplified method of quantitating protein using the biuret and phenol reagents. Analytical biochemistry, 86(1), 193-200.

- Percival, E. L., & McDowell, R. H. (1967). Chemistry and enzymology of marine algal polysaccharides. London.

- Pereira, L., & Neto, J. M. (Eds.). (2014). Marine algae: biodiversity, taxonomy, environmental assessment, and biotechnology. CRC Press.

- Schwarz, W. H. (2001). The cellulosome and cellulose degradation by anaerobic bacteria. Applied microbiology and biotechnology, 56(5), 634-649.

- Suganya, T., Gandhi, N. N., & Renganathan, S. (2013). Production of algal biodiesel from marine macroalgae Enteromorpha compressa by two step process: optimization and kinetic study. Bioresource technology, 128, 392-400.

- Tan, I. S., & Lee, K. T. (2014). Enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation of seaweed solid wastes for bioethanol production: An optimization study. Energy, 78, 53-62.

- Trivedi, N., Gupta, V., Reddy, C. R. K., & Jha, B. (2013). Enzymatic hydrolysis and production of bioethanol from common macrophytic green alga Ulva fasciata Delile. Bioresource technology, 150, 106-112

- Updegraff, D. M. (1969). Semimicro determination of cellulose inbiological materials. Analytical biochemistry, 32(3), 420-424.

- Wei, N., Quarterman, J., & Jin, Y. S. (2013). Marine macroalgae: an untapped resource for producing fuels and chemicals. Trends in biotechnology, 31(2), 70-77.

- Yanagisawa, M., Kawai, S., & Murata, K. (2013). Strategies for the production of high concentrations of bioethanol from seaweeds: production of high concentrations of bioethanol from seaweeds. Bioengineered, 4(4), 224-235.

|