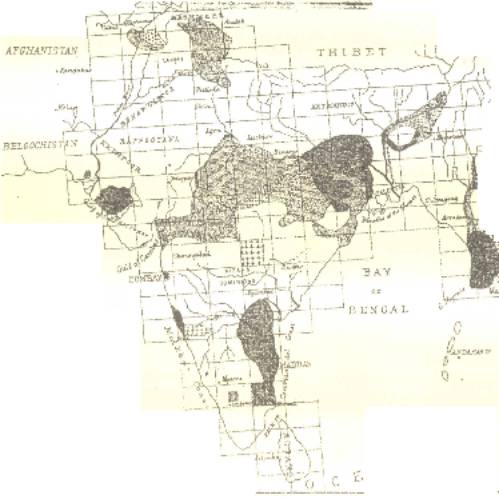

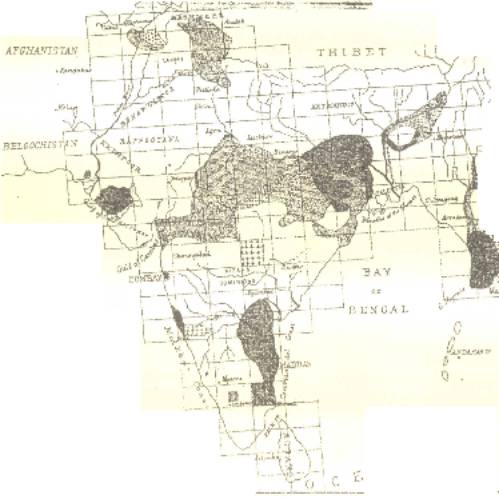

| Back | THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA. (With a Sketch-map.) |

By H. WOODWARD, F.G.S.

SIXTEEN years have now elapsed since the Geological Survey of India commenced its systematic labours, and it may now be interesting to give some account of the progress that has been made, and to note a few of the results to which the Government officers have been led.

Some time beforehand, in 1851, Mr. (now Dr.) T. Oldham, the Superintendent of the Survey, arrived in Calcutta. The work which he was then required to do was to go from place to place, and, without loss of time, to search for coal and other minerals of economic value; to furnish reports, and thus to indicate by observations in a few places the important results that might, be obtained from a detailed survey of the whole of the country. Great were the difficulties with which he had to contend at the outset, and for a long time afterwards; so that not until 1856 was he able to establish that regular system of operations carried on by a staff of officers, small at first, and even in 1863 numbering but fifteen geologists.

No one was better fitted for the task in hand than Dr. Oldham; he had been Local Director of the Geological Survey of Ireland, and was previously Professor of Geology in Trinity College, Dublin.

With his small band of Geologists, the Survey was carried on with vigour, and periodical reports were published, accompanied by maps, geologically coloured, and sections of the country described.

The value of the establishment was soon appreciated by the public, and numerous applications for reports on geological matters were made, as well as for aid in analyses of coal, minerals and ores, of soils, water, and in assays. Such information and assistance was given to many private individuals, as well as to Government departments and to companies. The earlier observations were, as might be expected, fraught with much difficulty. But few and isolated notices, compared with the size of the country, had been written upon it. The labours of Dr. Carter, of Bombay, of the Revs. Hislop and Hunter. Presbyterian missionaries in Tinnevelly, and some others, had certainly done a little towards paving the way for a classification of the rocks; and Mr. Greenough had, in 1854, after many years' labour in compilation, prepared a map of India, upon which he had depicted all that was then known concerning the geology of the country.

Dr. Oldham, ( See Mr. Homer's Anniversary Address to the Geological Society of London, 1861.) however, found it necessary to establish several new groups to receive (provisionally) the various rocks that were met with, in as much as for many and these some of the most widely-extended and important groups of rocks-there was no definite horizon from which to work either up or down. Over thousands and tens of thousands of square miles not a fossil was found, save some vegetable remains, affording, at the best, but very imperfect evidence. The richly fossiliferous rocks of the Himalaya and Sub-Himalaya being widely separated from all the rocks of the Peninsula by the broad expanse of the Alluvium, which unites the valleys of the Ganges and Indus, it was impossible to trace out, by their aid, any superposition.

To endeavour to remedy this, it was found advisable to examine many distinct tracts, and to make more or less rapid observations on distant parts, which, although interfering with the continuous progress of the Survey, were generally of essential service in leading to definite results on important geological points, which, in the ordinary progress of the work, could not have been arrived at for many years to come.

The climate of India necessarily restricts the work to certain portions of the year. The working season lasts about seven months, and differs very materially in the southern part of the Peninsula from that in Bengal. In the latter district, the close of the Indian financial year (the 31st March) nearly coincides with the close of the field season. In Madras the season is then not half over.

Considering the great exposure to which all field geologists working in the open country are unavoidably subjected, and the necessity for their visiting, and often remaining in, the most malarious and unhealthy parts, it is not surprising to learn that the whole staff are seldom at work at one time. The illness of one or more, and the necessity for leave of absence, is generally recorded in the Annual Reports. But it is grievous to learn the loss by death of five or six officers since the Survey has been in operation, whilst several have been forced to resign from ill-health.

These causes have occasioned much loss of time. It is seldom possible, Dr. Oldham remarks, to meet with persons qualified to supply the vacancies immediately. There is, moreover, absolute necessity for a considerable amount of training, occupying generally a year, before any newly-appointed Assistant can become really useful, and able to carry on alone the mapping of a district.

The pecuniary temptations furnished to individuals to join the Survey are not very great, the maximum ratio of pay being 500 and 600 rupees per month, but this is only obtainable after eight or ten years' service. The salary, as on the British Survey, is very fair to commence with, but equally discouraging in prospect.

The latest report of Dr. Oldham, dated the 3rd January 1870, is accompanied as usual by an index-map, showing the area surveyed, and published to the end of 1869, and that in progress. A reduced copy of this map accompanies our notice.

The Atlas of India, which includes Burmah and the Malay Peninsula, comprises about 180 sheets, portions of about' 64 of which have been mapped, while others have been visited and reported upon.

A very large area has not yet been surveyed topographically, so that the direction of the detailed mapping by the Geological Survey has some restrictions. The size of the sheets is 3 feet 4 1/8 inches by 2 feet 3 1/8 inches, and each contains an area of about 17,824 square miles.

The principal part of the work has been carried on in Central India. The faultiness of the existing maps of the country was found a serious drawback to successful progress, but so far as possible they were corrected, and every effort was made to render them of the utmost service. It was soon found, however, that the character of the geological work must be suited to the available maps of the district, and with very imperfect maps to attempt great detail would be useless. For all practical purposes, the boundaries of the geological formations could generally be fixed with sufficient accuracy.

But few sheets have been entirely surveyed. This, however, would be accounted for by the necessity, previously stated, of examining many different and distant parts for the purpose of arriving at a classification or knowledge of the order of superposition of the rocks in India; and when the vast area embraced by each sheet is taken into consideration, it is not surprising that few have been completed.

A glance at the map best shows the amount of fieldwork that has been done, and considering the many difficulties and dangers that have had to be encountered not forgetting the disturbed state of the country during the Indian mutiny in 1857-we must congratulate the Survey on the great progress it has made.

Besides the preparation and publication of the geological maps, the Survey now maintains three periodicals of letter-press.

The first part of the 'Memoirs' appeared in 1856, and since then six volumes have been completed, containing thirty-two geological reports (over 2200 pp. of letterpress), and the first part of vol. vii. has recently been published. All are well illustrated with maps and sections.

Particular attention has been given to the coal-bearing deposits. The 'Memoirs' contain reports on the Coalfields of Talchir, Ranigunj, Jherria, Bokaro, Ramgurh, &c.

The coal-fields of Bokaro and Ramgurh belong to the ordinary, or Damuda series.

In the Jherria coal-field, the two series, Talchir and Damuda, are developed.

The lower, or Talchir, contains no coal.

The Damuda series contains many seams, very irregular, and varying in thickness from a few inches to 20 feet and more. Numerous coal-seams are much injured by trap-dykes, which have ramified through them, and which have rendered the coal useless. There is also a general tendency to ignition in all the seams, owing, it is thought, to the presence of iron pyrites, which gives rise to spontaneous combustion. Metamorphism is produced in the shales in proximity, giving to them the character of well-burnt bricks.

Dr. Oldham calculates that there is an available quantity of coal in this Jherria field of about 465,000,000 cubic yards, or, roughly, tons of coal.

In Sinde there is a lignitic coal of Lower Tertiary age, but not worth working. In one of his earlier reports Dr. Oldham noticed the existence of Tertiary coal by the river Irrawaddy, near Prome.

Coal of excellent quality has been found in Assam, which lies near the river Brahmapootra, convenient for transport by water.

Considerable doubt attached to the age of the coalfields of Damuda, Talchir, and Nagpur. The reported discovery in them of certain plants was thought to place them in the Triassic or Oolitic period. But it has since been ascertained that these remains occur in shales above and distinct from the Coal-measures.

Comparisons have been made of late between the several series of sandstones, &c., associated with the coal in Bengal and those of Central India. The vast extension and great constancy in mineral character of the Talchir rocks (which form the base of the great coal-bearing series) have been fully established, and the thinning out of the beds in passing to the west has received further support. The entire Coal-formation, which in the east gives five well-marked subdivisions (in ascending order, Talchir, Barakar, Ironstone shales, Ranigunj, and Panchet), becomes, at a short distance to the west, only a threefold series, comprising the Talchir, Barakar, and Panchet subdivisions. Additional proofs have been brought forward to show that on the large scale, the present limits of these Coal-measures coincide approximately with the original limits of deposition, and are not the result of faulting, or even mainly of denudation.

And Dr. Oldham expresses his opinion that the great drainage basins of India were on the large scale marked out, and existed (as drainage-basins) at the enormously distant period, which marked the commencement of the deposition of the great plant-bearing series. In this point of view, local variations in the lithological type, local variations in the thickness of the groups, and even their occurrence or non-occurrence, are only necessary consequences of the mode and limit of formation.

In 1861 Dr. Oldham gave a summary statement of the amount of coal raised throughout India for the past three years, which was about 850,000 tons. The total amount of coal raised in India generally was, in 1858, about 226,140 tons; in 1859, about 347,227 tons; and in 1860, about 370,206 tons. Of this quantity the Ranigunj field yielded by far the greater part. The only mode of transport, however, from this field was by the river Damuda, a stream only navigable during the freshes of the rainy season, after which it becomes so dry that no more coal can be sent to market until the next season.

In 1867 Dr. Oldham made a report on the Coa1resources of India. (Being a return called for by the Right Hon. the Secretary of State for India.) The extensive fields which occur are not distributed generally over the country, but are almost entirely concentrated in one, a double, band of coal yielding deposit, which with considerable interruptions extends more than half across India, from near Calcutta towards Bombay.

Little more than surface workings are carried on the deepest pit scarcely exceed 75 yards, while certainly one-half of the Indian coal which has been used up to the present date has been produced from open workings or quarries.

Dr. Oldham concludes that out of the whole series of Indian coals, the very best of them only reach the average of English coals, and that on the whole they are very inferior to them. It should however, be borne in mind that until all the fields are carefully mapped, any estimates of the Coal-resources and production of British India must be defective.

Besides the coal-reports, the 'Memoirs' contain papers on the gold-bearing and other economic deposits, also many describing the geology generally and physical geography of particular areas. Some few treat of palaeontology.

One very important paper describes the Vindhyan series, as exhibited in the North-Western and Central Provinces of India. The district described included the greater part of Bundelkund. The Vindhyan series is divided into an upper and a lower division, the former gives rise to great table-lands, the latter furnishes more diversified scenery. The area affords many striking instances of the power and effects of subaerial denudation on a grand scale. As yet the Vindhyan rocks have yielded no fossils; they appear to be older than the Talchir, and may possibly turn out to belong to a period about the age of the Devonian. Lithologically they consist of alternations of limestones, shales, sandstones, and conglomerates, often distinguished by local names, as for instance the "Bijigurh shales". Some of the beds furnish good building stone.

In order to gain a more rapid publication of many isolated facts noticed during the progress of the Geological Survey, and which were scarcely adapted to the 'Memoirs,' a new publication called the 'Records' was started in 1868. The series contains notices of the current work of the Survey, lists of contributions to the Museum and Library, &c., and it is intended also to publish analyses of such books published elsewhere as bear upon Indian geology, and generally to notice all facts which come to light illustrative of the geology of Hindostan. The third volume is now in course of publication.

Among the numerous published Reports the following appear most worthy of special notice.

The Surat Collectorate, in the Bombay Presidency, although a comparatively flat country, possesses many features of geological interest. Traps, ranging from basalt to a soft shaly-looking amygdaloid, are met with, and resting unconformably upon these is the great Nummulitic series. This consists of sandstones, conglomerates, and limestones, with nummulites, molluscs, fossil-wood, and fragments of bone. Alluvium covers a large extent of the district, and the cotton (or black) soil covers it over many large tracts of the country. This soil seems to be the residuum left by the decomposition of an alluvium largely composed of volcanic (trappean) debris. It usually occurs in districts in which trap-rocks abound, as for example in the Poorna valley, West Berar.

The Poorna alluvium is of considerable depth, in places about 150 feet. Much of it produces efflorescences of salts, chiefly of soda; and in many places the wells sunk in it are brackish or salt.

Comparisons have recently been drawn between the Alluvial deposits of the Irrawadi and the Ganges. Every river, that discharges its waters into the sea has the character of its deposits influenced according to whether the area be in a state of subsidence, quiescence, or of elevation. Generally in every large river-basin two distinct alluvial deposits will be met with. The older of these may be either marine (estuarine) or fluviatile (lacustrine), or of a mixed and alternating character; but the newer group is essentially fluvio-lacustrine, and directly produced by the existing river. While no very great thickness of the newer stratum can anywhere have been deposited without a corresponding subsidence of the area, a very large accumulation of the older or estuarine deposit may have taken place during an elevation of the area covered by it.

The Ganges and Irrawadi present examples of rivers subjected, respectively, to the former and latter conditions. The alluvium of the Ganges, as ascertained from a well-boring at Fort William, consists of 70 feet of the newer or fluviatile deposit, resting on the denuded surface of the "kunker clay." This clay is regarded as an estuarine deposit accumulated during an upward movement of the land. The Gangetic area is now considered to be undergoing depression at a rate adequately counterbalanced by the accession of sediment brought down by the river. The alluvium of the Irrawadi belongs almost entirely to the older group, this river-delta being at the present time in precisely the same condition as was the delta of the Ganges when the first layers of its alluvium, 70 feet below the present surface at Calcutta, were being deposited. The difference in the fertility of the two areas is attributed to the greater richness of the newer alluvium, and hence the inability of the delta of the Irrawadi to compare with that of the Ganges in agricultural produce.

The geology of the neighbourhood of Madras is noticed in the third volume of the 'Records.' The greater part of this district is occupied by rocks of Secondary, Tertiary, and Recent ages, the remainder is taken up by metamorphic rocks, forming part of the great gneissic series of Southern India. Some time previously, beds of magnetic iron-ore were pointed out in the metamorphic gneiss rocks of the Madras Presidency, the supply of which was considered to be practically inexhaustible.

The Rajmahal plant-beds consist of conglomerates, sandstones, gritty clays, and shales.

The Laterite deposits are also pointed out. They comprise clayey conglomerates, gravels, and sands, which graduate one into the other. The gravels contain pebbles of quartzite and' gneiss, mixed with pisiform ferruginous pellets. Other deposits called the Conjeveram gravels are noticed; they differ from the laterite beds in the absence of ferruginous matter. Both appear to contain implements of human manufacture in the shape of axes and spear-heads made of chipped quartzite pebbles, and of the same types 88 those which occur in the gravels of Western Europe. They were spread rather widely over a large extent of area in the country to the west and north of the city of Madras, and have been made of the best substitute which this portion of the country could afford for flint, namely, the very hard and semi-vitreous quartzites of the Cuddapah series.

In gravel, situated near Pyton on the banks of the Godavery, an agate-flake has been found, which is undoubtedly an artificial form. It is figured in vo1.i. of the 'Records.'

We have but briefly and imperfectly noticed a few of the more important results arrived at by the energetic labours, in the field , of Dr. Oldham and the officers of the Geological Survey. This work-superintended by Dr. Oldham-has been carried out by the many able assistants who have served under him, among whom we may mention H. B. and J. G. Medlicott, H. J. and W. F. Blanford, C. AE. Oldham,( This able geologist died 30th March, 1869, Aged 37 years. See Obituary, 'Gevl, Mag.,' vo1.vi., p.240 . ) W. Theobald, jun., F. R. Mallet, A. B. Wynne, R.B. Foote, T. W. H. Hughes, W. King, jun., F. Fedden, &c.

We will now turn our attention to the palaeontological work.

A Museum of Economic Geology was established at Calcutta in 1840, and in 1856 it was placed in connection with and under the same superintendence as the Geological Survey of India. There are also Museums at Madras, Bombay, and Kurrachee.

During the progress of the Survey numerous fossils have been collected, and specimens are being constantly added to the Museum. Indeed Dr. Oldham reports that they increase so rapidly that no room can be found for their proper exhibition, and in the examination and description of them it is impossible to keep pace. During the year 1869 more than 20,000 specimens passed through the hands of the curator and his assistant. A suitable building is, we are informed, now in course of erection at Calcutta, where the fine collections already brought together will be properly arranged and exhibited.

One of the more richly fossiliferous tracts is at Spiti and Rushpu in the Himalayas, where representatives of Silurian, Carboniferous, Triassic (Lilang series), Rhaetic (Para limestone), Lower and Middle Lias, and three subdivisions of the Jurassic period, and also Cretaceous rocks are believed to occur.

In order to figure and describe the species of organic remains collected by the Survey, the 'Palaeontologia Indica' was instituted. This quarto publication is issued in fasciculi, each containing about six plates, and published once every three months. Five series of these fasciculi have been published.

The first series was printed in 1861, and treated of the Fossil Cephalopoda, of the Cretaceous rocks of South India, containing the Belemnitidae and Nautilidae, by H. F. Blanford; the Ammonitidae, by Dr. F. Stoliczka, formed matter for the third series.

The Cephalopoda were found to include 146 species, of which nearly one hundred were Ammonites, three only Belemnites, whilst of Nautilus there were 22 species, &c. Thirty-seven of these species were found identical with species known in Europe and other countries. Ninety-six quarto plates are devoted to the illustration of these fossils.

The Gasteropoda of the Cretaceous rocks form the subject of the fifth series; they are illustrated with sixteen plates, and are described by Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka.

Two hundred and thirty-seven species of Gasteropoda are described. Among them, four species of Helicidae are deserving of special attention from the rarity of landshells in these Cretaceous rocks, and particularly as they are said to belong to types still found living in the same or neighbouring districts.

Dr. Stoliczka considers that the South Indian Cretaceous deposits only represent the Upper Cretaceous strata, beginning with the Cenomanien. The larger number of representative species were found to agree with the Turonien. The original notion of representatives of Neocomian beds existing in South India loses support from the more complete examination and comparison, of the species.

The second series of the 'Palaeontologla Indica' is devoted to the Fossil Flora of the Rajmahal series (Jurassic), six fasciculi of which have been published. The descriptions are by Dr. Oldham and Professor Morris. The Rajmahal beds occur near Madras, in Bengal, and Kutch. At Madras the beds contain no carbonaceous matter, which in their equivalents in other parts of India occurs so largely as to form coal-seams. The plantremains occur chiefly in a white shale. They include Palaeozamia, Dictyopteris, Taeniopteris, Pterophyllum, Pecopteris, Stangerites, Poacites, &c.

The fourth series on the Vertebrate Fossils of the Panchet rocks is by Professor Huxley, and is illustrated with six plates. These remains consist of numerous fragmentary and sometimes rolled bones, the majority being vertebrae, with a few teeth, portions of crania, &c. They were discovered in a stratum of conglomerate sandstone exposed by the Damuda river near Deoli, fifteen miles west of Ranigunj, and they are of great interest as being the first remains of vertebrata discovered in the great group of rocks associated with the coalbearing formations of Bengal. They proved to belong to a peculiar group of fossil reptiles (Dicynodontia) hitherto only known from South Africa. The strong analogy which these South African rocks offer to some of the Indian rocks had been insisted on by Dr. Oldham, before this discovery, on the strength of the plant-remains alone, and this has been strangely confirmed by the discovery of reptiles of the same type (Dicynodontia).

Very many years must necessarily pass away before the Geological Survey of India is completed, nor can Dr. Oldham and his present staff hope to see its accomplishment, but they have done sufficient already to indicate the great geological features of the country, and we may hope to see in one of their future publications, a table of succession of the Indian strata as far as at present determined, with their probable European equivalents.