| Theme: 2. Lakes—Conservation, Restoration, Management | Papers | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

Hydro-geo morphological and ecological studies of certain Lentic Water bodies in the mid Western Ghats of Karnataka with Special reference to Shimoga Taluk, Karnataka |

|

J Narayana and R Purushotham |

|

Department of Environmental Sciences,

Kuvempu University,

Shankara Ghatta,

Karnataka-577 451

Emerging phytotechnologies for remediation of heavy meal polluted and contaminated soil and water |

|

Abstract

Contemporary world is facing problems with a wide variety of pollutants and contaminants (both inorganic and organic). Healthy soil, celan water and air are the soul of life. Often soil, water and air are no longer clean and pure posing human health risks. The supposedly most pristine environment in arctic circle and Antarctica are not even spared due to global transport of anthropogenic pollutants/contaminants of three major groups viz, i) heavy metals ii) acidifying gases (SOx), and iii) variety of persistent organic pollutants that play a major role in global climate change. This presentation would concentrate only on inorganic pollutants and application of emerging phytotechnologies for environmental cleanup and resoration. The contamination of the environment with toxic metals has become a world wide problem, affecting crop yields, soil biomass and fertility,contributing for the bioaccumulation and biomagnifications in the chain. In the last few decades, research groups have recognised that certain chemical pollutants such as toxic metals may remain in the environment for a long period and can eventually accumulate to levels that could harm humans. Moreover, the numerous classes and types of these chemicals apart from the soil structure complicate the removal of many toxic metals from the environment. As an alternative, an ecological technological approach has been developed involving the use of plants to clean up or remediate soils contaminated with toxic metals. A group of plants, termed "hyper-accumulators" are the best candidates capable of toxic metal uptake, transport and accumulate.

Introduction

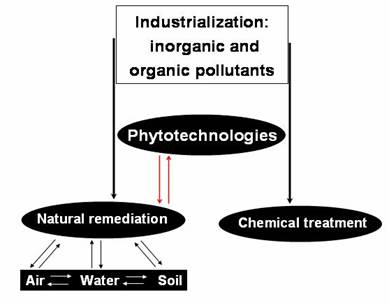

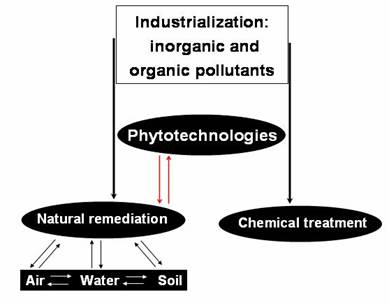

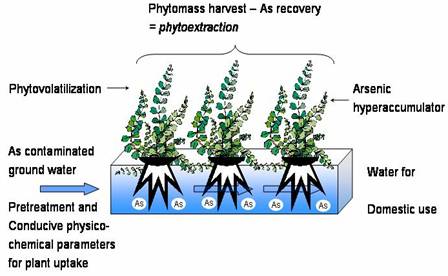

A wide range of phytoechnologies have emerged as a feasible technology for environmental restoration (Glass 1999, McCutcheon and Schnoor 2003). The wide reocgnitions for this approach is is supported by the fact that it is considered to be an environmentally friendly technology, safe and also a cheap way to remove contaminants, in some cases doing the same job as a group of engineers for one tenth of the cost. In this presentation the upcoming phytotechnologies for inorganic pollutants in soil and water such as phytoextraction, phytostabilization, phytostimulation, phytovolatilization, hydraulic barriers for containment of groundwater migration, vegetative caps for containment of landfill leachate, constructed wetlands, riparian buffer zones and buffer zones for stormwater detention, Environmental restoration for erosion control, halophytic (salt-loving) plants, environmental crops. Phytotechnologies are being commercialized in developed world (Glass 1999, McCutcheon and Schnoor 2003) (Figure 1 and 2)

The contamination of the environment with toxic metals has become a worldwide problem, affecting crop yields, soil biomass and fertility, contributing for the bioaccumulation and biomagnifications in the food chain (Table 1). In the last few decades, research groups have recognised that certain chemical pollutants such as toxic metals may remain in the environment for a long period and can eventually accumulate to levels that could harm humans. Biological and engineering strategies designed to improve the use of phytoremediation to reduce the amount of heavy metals in contaminated soils has begun to emerge (Adriano et al 2004).

Phytoremediation is a general term for several ways in which plants are used to clean up, or remediate, sites by removing pollutants from soil and water. Plants can break down, or degrade, organic pollutants or contain and stabilize metal contaminants by acting as filters or traps. Some of the methods that are being tested are described in this fact sheet. Treating metal contaminants at sites contaminated with metals, plants are used to either stabilize or remove the metals from the soil and ground water through three mechanisms: phytoextraction, rhizofiltration, and phytostabilization. Phytoextraction, also called phytoaccumulation, refers to the uptake and translocation of metal contaminants in the soil by plant roots into the aboveground portions of the plants. Certain plants, called hyperaccumulators, absorb unusually large amounts of metals in comparison to other plants. One or a combination of these plants is selected and planted at a particular site based on the type of metals present and other site conditions. After the plants have been allowed to grow for some time, they are harvested and either incinerated or composted to recycle the metals. This procedure may be repeated as necessary to bring soil contaminant levels down to allowable limits. If plants are incinerated, the ash must be disposed of in a hazardous waste landfill, but the volume of ash will be large.

Indigenous microorganisms are those microorganisms that are found already living at a given site. To stimulate the growth of these indigenous microorganisms, the proper soil temperature, oxygen, and nutrient content may need to be provided. If the biological activity needed to degrade a particularcontaminant is not present in the soil at the site, microor-ganisms from other locations, whose effectiveness has been tested, can be added to the contaminated soil. These are called exogenous microorganisms. The soil conditions at the new site may need to be adjusted to ensure that the exogenous microorganisms will thrive.

Essential processes involved in phytoremediation:

Constructed wetlands for water treatment

Stormwater is a important water resource. S tormwater treatment and management is an important topics in tropical countries. In the wake of 2005 Bangalore and Mumbai urban flash floods all concerned authorities must examine the feasibility of implementing “Sustainable Urban Drainage Systems (SUDS)” a well established and operationalized in developed counties. This is a neglected area in Indian scenario.

The use of aquatic plants in water quality assessment has been common for years as in-situ biomonitors and for in situ remediation . The occurrence of aquatic macrophytes is unambiguously related to water chemistry and using these plant species or communities as indicators or biomonitors has been an objective for surveying water quality. Aquatic plants have also been used frequently to remove suspended solids, nutrients, heavy metals, toxic organics and bacteria from acid mine drainage, agricultural landfill and urban storm-water runoff. In addition considerable research has been focused on determining the usefulness of macrophytes, as biomonitors of polluted environments and as bioremediative agents in waste water treatments (Fritioff and Greger 2003, Mohan and Hosetti 1999, Kamal et al 2004, Lytle et al 1998). The response of an organism to deficient or excess levels of metal (i.e. bioassays) can be used to estimate metal impact. Such studies done under defined experimental conditions can provide results that can be extrapolated to natural environment. There are multifold advantages in using an aquatic macrophyte as a study material. Macrophytes are cost-effective universally available aquatic plants and with their ability to survive adverse conditions and high colonization rates, are excellent tools for studies of phytoremediation. Rooted macrophytes especially play an important role in metal bioavailability through rhizosphere secretions and exchange processes. This naturally facilitates metal uptake by other floating and emergent forms of macrophytes. Macrophytes readily take up metals in their reduced form from sediments, which exist in anaerobic situations due to lack of oxygen and oxidize them in the plant tissues making them immobile and bioconcentrate them to a great extent. Metals concentrated within macrophytes are available for grazing by fish. These may also be available for epiphytic phytoplankton, herbivorous and detrivorous invertebrates. This may be a major route for incorporating metals in the aquatic food chain. It is therefore of interest to assess the levels of heavy metals in macrophytes due to their importance in ecological processes. The immobile nature of macrophytes makes them a particularly effective bio-indicator of metal pollution, as they represent real levels present at that site. Data on phytotoxicity studies are considered in the development of water quality criteria to protect aquatic life, the toxicity evaluation of municipal and industrial effluents ( APHA-American Public Health Association 1998) . In addition aquatic plants have been used to assess the toxicity of contaminated sediment elutriates and hazardous waste leachates.

In the past research with macrophytes has centered mainly on determinig effective eradication techniques for nuisance growth of several species such as Elodea Canadensis, Eichhornia crassipes, Ceratophyllum demersum etc. Scientific literature exists for the use of wide diversity of macrophytes in toxicity tests designed to evaluate the hazard of potential pollutants, but the test species used is quite scattered. Similarly literature concerning the phytotoxicity tests to be used, test methods and the value of the result data is scattered. Estuarine and marine plant species are being used considerably less than freshwater species in toxicity tests conducted for regulatory reasons. The suitability of a test species is usually based on the specimen bioavailability, sensitivity to toxicant, reported data and the like. The sensitivity of various plants to metals was found to be species and chemical specific, differing in the uptake as well as toxicity of metals. Many submersed plants have been used as test species, but there is no widely used single species. In a literature survey only 7% of 528 reported phytotoxicity tests used macrophytic species (Wang and Freemark 1995). Their use in microcosm and mesocosm studies is even rarer and has been highly recommended. Several plant species like Lemna, Myriophyllum, Potamogeton have been exhaustively used in phytotoxicity assessment, but several others have been given less importance as a bioassay tool. Duckweeds have recieved the greatest attention for toxicity tests as they are relevant ot many aquatic environments, including lakes, streams, effluents. Aquatics encompassing:

Eichhornia crassipes , Elodea Canadensis, Heteranthera dubia, Myriophyllum spicatum, Potamogeton pectinatus, P.richardsonii, Vallisneria American, V. spiralis, Wolffia globosa, Lemna trisulca, Hydrilla verticillata and Typha latifolia have been almost extensively studied both in lab and field.

Metal concentration Factor : [Metal] plant (g/g dry wt) [ Meta ] water(g/mL)

Pollutants that originate mainly from non-point sources, which are difficult to control. Constructed wetlands are designed to intercept and remove a wide range of contaminants from waste water. These wetlands can save time and money by using natural mechanisms to treat non-point source pollution before it reaches lakes, rivers, and oceans. Conventional wastewater treatment plants can effectively remove non-point source pollution, but are expensive to build and operate. Therefore, local waste water treatment plants are desirable to reuse water.

The most important role of plants in wetlands is that they increase the residence time of water, which means that they reduce the velocity and thereby increase the sedimentation of particles and associated pollutants. Thus they are indirect involved in water cleaning. Plants also add oxygen providing a physical site of microbial attachment to the roots generating positive conditions for microbes and bioremediation. For efficient removal of pollutants a high biomass per volume of water of the submerged plants is necessary. Uptake of metals in emergent plants only accounts for 5% or less of the total removal capacity in wetlands. Not many studies have been performed on submerged plants, however, higher concentration of metals in submerged than emerged plants has been found and in microcosm wetland the removal by Elodea canadensis and Potamogeton natans showed up to 69 % removal of Zn. ( Kadlec 1995; Kadlec and Knight 1996)

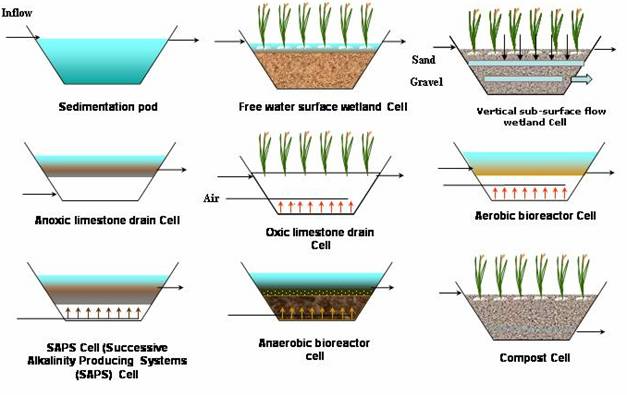

Constructed and engineered wetlands for water treatment (Figures 3-8; Okurut et al 1999)

Natural wetlands

Constructed wetlands

Potential role of aquatic plants in phytotechnology

Phytoremediation is defined as the use of plants for environmental cleanup (Prasad 2007). (Table 2 and 3) Aquatic macrophytes have paramount significance in the monitoring of metals in aquatic ecosystems (eg: Lemna minor, Eichhornia crassipes, Azolla pinnata) Aquatic plants are represented by a variety of macrophytic including algal species that occur in various habitats. They are important in nutrient cycling, control of water quality, sediment stabilization and provision of habitat for aquatic organisms. The use of aquatic macrophytes in water quality assessment has been a common practice employing in-situ biomonitors (Sobolewski 1999)

The submerged aquatic macrophytes have very thin cuticle and therefore readily take up metals from water through the entire surface. Hence the integrated amounts of bioavailable metals in water and sediment can be indicated to some extent by using macrophytes. Macrophytes with their ability to survive adverse conditions and high colonization rate are excellent tools for phytoremediation. Further they redistribute metals from sediments to water and finally take up in the plant tissues and hence maintain circulation. Benthic rooted macrophytes (both submerged and emergent) play an important role in metal bioavailability from sediments through rhizosphere exchanges and other carrier chelates. This naturally facilitates metal uptake by other floating and emergent forms of macrophytes Macrophytes readily take up metals in their reduced form from sediments, which exist in anaerobic situations due to lack of oxygen and oxidize them in the plant tissues making them immobile and hence bioconcentrate them to a high extent Okurut et al 1999)

Constructed wetlands are man-made wetlands designed to intercept and remove a wide range of contaminants from water. These wetlands can save you time and money by using natural mechanisms to treat non-point source pollution before it reaches our lakes, rivers, and oceans. oils, nutrients, suspended solids, and other substances. These pollutants originate mainly from non-point sources, which are difficult to control. Conventional wastewater treatment plants can effectively remove non-point source pollution, but are expensive to build and operate.

Treatment mechanisms

Filtration and uptake of contaminants.

Settling of suspended solids due to decreased

Water velocity and trapping action of plants, leaves, and stems.

Precipitation, adsorption, and sequestration of metals.

Microbial decomposition of petroleum hydrocarbons and other organics

Benefits

Cost-effective treatment of non-point source pollution.

Compliance with water quality goals.

Reduction of operation and maintenance costs relative to conventional water treatment plants.

Conservation of natural resources.

Reduction of flood hazard and erosion.

Creation of wildlife habitat and aesthetic resource.

Plants may reduce element leakage from submerged mine tailings by phytostabilisation. However, high shoot concentrations of elements might disperse them and could be harmful to grazing animals. Plants that are tolerant to elements of high concentrations have been found useful for reclamation of dry mine tailings containing elevated levels of metals and other elements. Mine tailings rich in sulphides, e.g. pyrite, can form acid mine drainage (AMD) if it reacts with atmospheric oxygen and water, which may also promote the release of metals and As. To prevent AMD formation, mine tailings rich in sulphides may be saturated with water to reduce the penetration of atmospheric oxygen. An organic layer with plants on top of the mine tailings would consume oxygen, as would plant roots through respiration.

Thus, phytostabilisation on water-covered mine tailings may further reduce the oxygen penetration into the mine tailings and prevent the release of elevated levels of elements into the surroundings. Metal tolerance can be evolutionarily developed while some plant species seem to have an inherent tolerance to heavy metals. Since, some wetland plant species have been found with the latter property, for example Thypha latifolia , Glyceria fluitans and Phragmites australis , wetland communities may easily establish on submerged mine tailings, without prior development of metal tolerance. The relationships between element concentrations in plants and concentrations in the substrate differ between plant species. Some plant species have mechanisms that make it possible to cope with high external levels of elements. Low-accumulators are plants that can reduce the uptake when the substrate has high element concentrations, or have a high net efflux of the element in question, thus the plant tissue concentration of the element is low even though the concentration in the substrate is high (Williams 2002., Wood and Mcatamney 1994, Woulds and Ngwenya 2004, and Ye et al 2001)

Conclusions

Figure 1: Air- Water- Soil (rhizosphere – plant) continuum, the basis for natural attenuation of contaminants and pollutants needs critical study for successful implementation of phytotechnologies

Figure 2: Various sub-processes in phytotechnologies

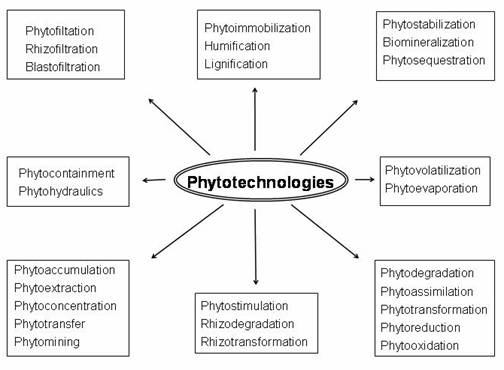

Figure 3: Removal of Arsenic from ground water using macrophytes by phytovolatilization ( Aksorn and Visoottiviseth 2004).

Figure 4: Constructed wetland technology for treatment of municipal waste waters using macrophytes.

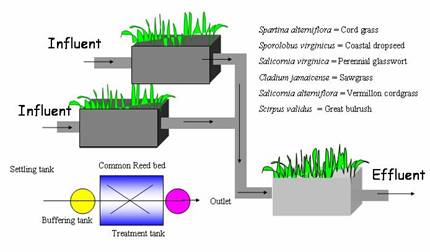

Figure 5: Cascade model of constructed Aquaplant with cmmon reed beds or grasses for the removal of xenobiotics and treatment of saline waste streams. The commonly used grasses for the treatment of saline waste strems are Spartina alterniflora = Cord grass, Sporolobus virginicus = Coastal dropseed; Salicornia virginica = Perennial glasswort; Cladium jamaicense = Sawgrass; Salicornia alterniflora = Vermillon cordgrass; and Scirpus validus = Great bulrush

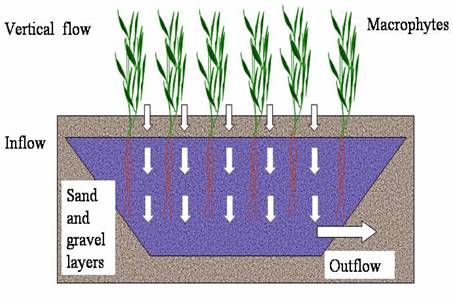

Figure 6: Constructed wetland for removal waste water treatment (Vertical flow system with macrophytes)

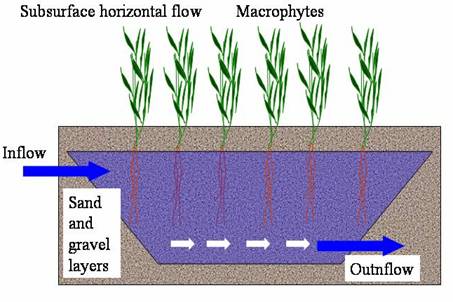

Figure 7: Constructed wetland for removal waste water treatment (Horizontal flow with macrophytes)

Figure 8: Ideal system for assessing the rhizofiltration in hydropinics using Talinum cuneifolium (Portulacaceae)

Environmental crops

e.g. Brassica juncea & Helianthus annus Abundant biomass

Trace element accumulation including radionuclides

Figure 9: Environmental crops for phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soils

Contaminant |

Pollutant |

Trace amount in the ambient environment and the organism exposed to contaminant may not show visible toxic symptoms |

Comparatively larger in amount in the ambient environment. The organism exposed would exhibit visible toxic symptoms |

Table 2: Aquatic plants for and biomonitoring of toxic trace elements in a wide range of toxicity bioassays (Prasad 2007, Prasad (2001a,b, 2004 a,b, 2006, 2007, Prasad and Freitas 2003, Prasad et al 2001, 2006 )

| Plant species | Metal |

| Azolla fililiculioides | Cr, Ni, Zn, Fe, Cu, Pb |

| A. pinnata | Cd, Cr, Zn |

| Bacopa monnieri | Hg, Cr, Cu, Cd |

| Carex juncell | Cu, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, Mo, U |

| Carex rostrata | Cu, Pb, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, Mo, U |

| C arex Sp. | Cd, Fe, Pb.,Mn |

| Ceratophyllum demersum | Cd, Cu, Cr, Pb, Hg, Fe, Mn. Zn, Ni, Co and radionuclides |

| Cyperus eragrostis | Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn |

| Distichlis spicata | Cd, Fe, Pb, Mn |

| Elodea densa | Hg, methyl-Hg |

| E. nuttallia | Cu |

| E. sptangulare | Hg, Pb, Cd, Cu and Fe |

| Eichhornia crassipes | As, Cd, Co, Cr Cu, Al, Ni, Pb, Zn, Hg, P, Pt, Pd, Os, Ru, Ir, Rh |

| Elodea canadensis | Cu, Pb, Cd, Zn, Cr, Ni |

| Eriocaulon septangulare | Hg, Pb, Cd, Fe |

| Euryale ferox | Cd,Cr,Pb, Cu |

| Hydrilla verticillata | Hg, Fe, Ni, Hg, Pb |

| Hygrophila onogaria | Hg, methyl-Hg |

| Isoetes lacustris | Cu. Pb |

| Lemna minor | Mn, Pb, Ba, B, Cd, Cu, Cr, Ni, Se, Zn, Fe |

| L. trisulca | Cu, Cd |

| L. gibba | Cu, Cd |

| L. palustris | Zn, Cu, Fe, Hg |

| L. paucicostata | Cd, Zn, EDTA, Cu, Ca |

| L. perpusilla | Cd |

| L. polyrrhiza | Cd |

| L. valdivinia | Cd, Cu |

| Littorella uniflora | Cu, Pb |

| Ludwigia natans | Hg, methyl-Hg |

| Lysimachia nummularia | Hg, methyl-Hg |

| Myriophyllum spicatum | Cd, Cu, Zn, Pb, Ni, Cr |

| M. alterniflorum | Cu, Pb |

| M. exalbescens | Zn, Pb |

| M. aquaticum | Zn, Cu, Fe, Hg, Cd, Pb |

| Melilotus indica | Se |

| Mentha aquatica | Cd, Zn, Cu, Fe, Hg |

| Najas marina | Cd, Fe, Pb, Mn |

| Nasturtium officinale | Cd |

| Nuphar lutea | Cu, Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Mn, Pb, Cd, Hg, Fe |

| N. variegatum | Cu, Zn |

| Nymphaea alba | Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Mn, Pb, Cd, Cu, Hg, Fe |

| Nymphoides germinate | Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn |

| Potamogeton attenuatum | Cd, Cu. Pb. Zn |

| P. communis | Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Mn, Pb, Cd, Cu, Hg, Fe |

| P. crispus | Cu, Pb, Mn, Fe, Cd |

| P. filiformis | Cd, Fe, Pb, Mn |

| P. lapathifoilum | Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn |

| P. orientalis | Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn |

| P. pectinatus | Mn. Pb, Cd, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, As, Se |

| P. perfoliatus | Cu, Pb, Cd, Zn, Ni, Cr |

| P. richardsonii | Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Zn, Pb |

| P. subsessiles | Cd, Cu. Pb. Zn |

| Phragmites karka | Cr |

| Pistia stratoites | Cu, Al, Cr, P, Hg |

| Ranunculus aquatilis | Mn, Pb, Cd, Fe, Pb, |

| R. baudotii | Cd, Cu, Cr, Zn, Ni, Pb |

| Ruppia maritima | Mn, Pb, Cd, Pb, Fe, Se |

| Salvinia acutes | Mn, Pb |

| S. maritimus | Cd, Fe, Pb, Mn |

| S. natans | Pb, Cr |

| S. undulata | Pb |

| S. molesta | Hg |

| Scapania uliginosa | B, Ba, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Li, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, Sr, V, Zn |

| Schoenoplectus lacustris | Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Mn, Pb, Cd, Cu, Hg, Fe |

| Scirpus lacustris | Cr |

| Spirodela polyrhiza | Cr |

| Typha domingensis | Cd, Cu, Pb, Zn |

| T latifolia | Ni, Cr, Co, Zn, Mn, Pb, Cd, Cu, Hg, Fe |

| Vallisneria americana | Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn |

| V. spiralis | Hg |

| Wolffia globosa | Cd, Cr |

Table 3: Aquatic macrophyts a for phytotechnologies to treat inorganic pollutants, acid mine drainage, salt water, regulation of storn water and removal of radionuclides. For details of experiments (field and laboraroty), reference may be made to COST action 837, 2003 and COST action 859, 2005, Hattink et al 2000, McCutcheon and Schnoor 2003, Peles et al 2002, Prasad (2001a,b, 2004 a,b, 2006, 2007, Prasad and Freitas 2003, Prasad et al 2001, 2006 )

Plant name |

Common name |

Phytormediation function |

| Azolla filiculoides | Water fern | Metals hyperaccumulation |

| Bacopa monnieri | Water hyssop | Metals accumulation |

| Canna flaccida | HM removal in constructed wetland | |

| Carex pedula | HM removal in constructed wetland | |

| Chara, Nitella, Mougeotia, Ulothrix | Algae | If they could be induced to grow mining effluents, they would provide a simple, long-term solution remove U and other radionuclides |

| Cladium Jamaicense | Sawgrass | Brine concentration |

| Eichhornia crassipes | Water hyacinth | Metals accumulation and biosorption |

| Elodea canadensis | Phytofiltration of storm water and removal of zinc | |

| Eriophorum angustifolium | Phytostabilization of metal rich mine tailings | |

| Eriophorum scheuchzeri | Phytostabilization of metal rich mine tailings | |

| Glyceria fluitans | Phytostabilization of mine tailings, treatment of acid mine drainage | |

| Hydrilla verticillata | - | TNT transformation and metals accumulation |

| Hydrocotyle umbellata | Pennywort | Biosorption of toxic metals |

| Ipomea aquatics | Water spinach | Metals accumulation |

| Juncus articulatus | Phytostabilization of mine tailings | |

| Lemna minor | Duck weed | Concentrates technetium-99 |

| Lemna, Spirodela and Wolffia | Duckweeds | Biosorbents of inorganic and organic pollutants and metals accumulation |

| Miscanthus floridulus | HM removal in constructed wetland | |

| Miscanthus sacchariflorus | HM removal in constructed wetland | |

| Nymphaea violacea | waterlily | uranium and thorium series radionuclides |

| Pistia stratiotes | Water lettuce | Metals accumulation |

| Polygonum punctatum | radiocesium ( 137 Cs) | |

| Potamogeton natans | Phytofiltration of storm water and removal of zinc | |

| Potamogeton natans | - | Metals uptake |

| Sagittaria latifolia | radiocesium ( 137 Cs) | |

| Salvinia molesta | Kariba weed | Metals accumulation |

| Scirpus spp | Bulrush | Used in constructed wetland |

| Scirpus validus | - | Brine concentration |

| Spartina alterniflora | Cordgrass | Saltwater, brine concentration |

| Spirodela oligorrhiza | Giant duckweed | metals accumulation |

| Sporobolus virginicus | Coastal dropseed | Brine concentration |

| Tamarix spp. | Salt cedar | Hydraulic control of arsenic |

| Vallisneria spiralis | Eel grass | Metals hyperaccumulation |

| Zizania aquatica | wild rice | Uptake of 129 I. |

References

M.N.V. Prasad, Department of Plant Sciences

School of Life Sciences

University of Hyderabad

Hyderabad 500046 AP, India Tel: +91-40-23011604, 23134509 (Direct lines) Fax: +91-40-23010120/23010145 E-mail: mnvsl@uohyd.ac.in